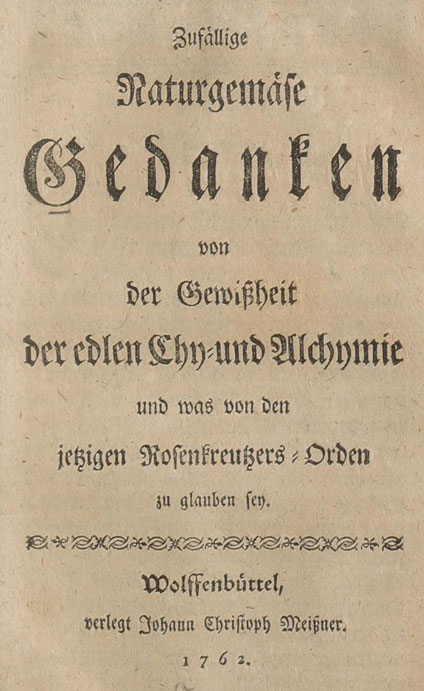

Casual Natural Thoughts on the Certainty of the Noble Chy- and Alchymy, and what is to be believed concerning the present Order of the Rosicrucians

Listen Audio Book Buy me CoffeeCasual Natural Thoughts

on

the Certainty

of the Noble Chy- and Alchymy,

and what is to be believed

concerning the

present Order of the Rosicrucians.

Wolfenbüttel,

published by Johann Christoph Meißner.

1762.

Translated from the book:

"Zufällige Naturgemäse Gedanken von der Gewißheit der edlen Chy- und Alchymie und was von den jetzigen Rosenkreutzers-Orden zu glauben sey"

Preface

It is not my intention, through these mixed and incidental thoughts, to serve the reader as a master and teacher of alchemy, but rather to give occasion to consider the matter itself without prejudice.

Those who have once been seized by prejudice are accustomed to judge a matter without reflection and to contradict everything — especially, however, concerning alchemy, which in part finds such belief that anyone can freely and publicly declare: He can make gold — well knowing that no one will believe him.

Others again, in view of their own interests, are far too credulous and thus easily deceived. Since they do not first consider the workings of nature, but only with wide eyes and outstretched arms they grasp after gold, though a contented soul and sound body are to be preferred above all earthly treasures. Only he seeks rightly in alchemy who looks therein for medicine against sickness.

I hope that no one will be offended by these few lines, since I present to each only my own thoughts. It would be desirable, however, that deceivers and profaners of this noble science would desist from their godlessness and no longer offend God and their neighbor; whereas honest adepts should not keep themselves so hidden, but rather, in these troubled times, should observe the love of their neighbor. For love is the foremost duty of all Christians, and apart from love, all sciences are of no use.

Random Natural Thoughts

Among all matters in the whole world, none is treated more unreasonably than that of alchemy.

The noblest medicines that can be prepared from it are denounced by many unskilled doctors as poisons—because, when all vegetable substances no longer avail, they themselves must turn even to the mineral realm, seizing metals and minerals in order to draw from them a crocus or salt, from which they first extract a tincture and apply the shells, while leaving the kernel aside.

It cannot, indeed, be denied that even the shells of nuts may at times be of use, especially in certain cases to which many virtues are ascribed; yet only a metal or mineral, in its purest form, should display such efficacy as is natural to it, once it has been properly cleansed and reborn, and its inner essence brought forth. For the spirit is what acts—as Basilius teaches in his fourth Key.

Granted even that the alchemists dealt solely with poisons — is this indeed so utterly detestable, since the same, when its volatile nature has been tamed, suddenly manifests, in its purified form, the life-spirit of man? For though, on account of its highest volatility, it may at first appear harmful, yet the question remains whether, when the poison’s volatility and corrosiveness are removed, it may not rather become a wholesome medicine and a strengthening power in nature.

It occurs to me that a flower, which is beautiful and good, delights men by its color and fragrance. The bee makes from it the sweetest honey, the spider, however, poison. Whether this lies in the flower or in the creature, is a matter for further investigation.

But let us now return to the principal subject of the alchemists and the foundation of philosophy with occasional reflections.

Those worldly-wise and learned men who still admit that the transmutation of metals is possible, cannot humble themselves so far as to believe that they must seek the true beginning in a base and despicable subject, which God, the All-wise, has placed in nature — for nature must everywhere be the guide of all things, and, according to the utterance of the Creator, each brings forth its like, that which bears its own seed within itself.

Accordingly, by the reasoning of the learned scholars, gold must relinquish everything that alchemy requires of it — though they themselves should see that the molten corporeal gold is, in itself, dead, and possesses nothing beyond what it needs for its own perfection; rather, they should have greater cause to consider the beginnings of gold itself.

If animals are to beget animals, they need not first be destroyed and burned; instead, nothing more is required than that they be placed with their seed into the proper matrix and entrusted to nature — not in a violent manner, but in the gentlest love. Yet this seed is no corporeal animal, but merely a spiritual, slimy moisture, from which, in due time, a perfect animal is nevertheless generated.

If we now consider the vegetabilia and their transmutation, we see that the seed, cast into the earth or mingled with its own water, which is homogeneous to it, swells in a viscous moisture, whereby it is, as it were, dissolved; yet by its own fire it is ignited, revives, and is reborn, and unfolds its growing power into a small sprout.

This little sprout is finally, in its natural time, brought forth by nature into a tree, shrub, or ear of grain, and bears fruit a hundredfold after its own kind, from which the seed was taken.

But if, from this seed, the first emerging sprout were broken off and destroyed, no fruit could ever arise; or if one were to crush or burn the seed, and afterward sow such a one, how could any reasonable transmutation ever occur?

We thus see that even if all imagined wisdom were set aside, all animals and vegetables have one and the same beginning — namely, a slimy moisture.

That also the mineral kingdom has, in this respect, its own beginning and continuation cannot reasonably be doubted; yet mankind is to blame that this transmutation is not better known, since men are unwilling to let nature work in this firm realm, but rather, through their impatience, rush now upon this, now upon that subject — now roasting minerals, now melting metals. They proceed so foolishly that even that even human excrements are not spared in this manner — not considering that what a man sows, that shall he also reap.

The Aurea Catena Homeri says in general: The Above is as the Below, and the Below as the Above, and proves very naturally that all things are born of water.

If minerals and metals are indeed born from water, then these can likewise, by nature, be brought back into such a watery state, and the first moist principle of growth be restored.

We see, moreover, in animals and plants, that such seed must be very pure and fertile, for when the earth is cast out from nature, and is without its nutritive juice, it can show no growth; therefore, it must necessarily also be moist.

I would have to prove this proposition, that it is indeed possible to bring back minerals and metals into a watery state; this, however, is impossible — all experimenters and chemists know that, with their harshly corroding waters, they can only bring them back into a vitriol, from which, according to Basil, the three Principia — namely Mercurius, Sulphur, and Sal — are separated.

For the philosophers assert that all things consist of these principles; yet if these fools were reasonable, they would refrain from strife and contention. For if they mixed such waters with minerals and metals, they would soon realize that these waters are not homogeneous with them; indeed, they have, to their great harm and that of many others, learned—by bitter experience—that their hoped-for gold, together with what little they possess, vanishes into smoke and vapor up the chimney.

The true modum procedendi (method of procedure) the philosophers do not conceal without reason. Yet they give the lovers of nature some guidance, by which the misuse of this art has been, to some extent, prevented.

Nevertheless, through this noble art much deceit has been introduced into the world. Many impostors and gold-greedy men have wickedly imitated it, and Satan, as the enemy of all good sciences, has succeeded in sowing his seed among them through godless deceivers.

And since many wondrous sums have been squandered upon it, and so many experiments have failed, true philosophy has been so discredited by such impostors that it is regarded by most as impossible.

Yet should one or another person still resolve to apply himself to this science and to investigate nature, then neither opposition nor persecution should no hindrance be — and he will, though not openly, yet secretly, be regarded by fools as a madman, since, according to the common proverb, “Every man likes his own cap.”

Nevertheless, many great lords have been found who sought their pleasure therein; and though they did not all meet with such happy success as Count Bernardus, yet our art of medicine shines forth with glorious remedies, discovered through such experiments. But these have now become ever rarer, since noble alchemy has grown so hateful to most men.

That all things have their beginning in a slimy moisture has already been shown; yet the animalia have a different moisture from the vegetabilia, and so also the minerals — though they all have their origin from the general world-moisture, as all philosophers agree, even if they seem to contradict one another in other particulars.

For all minerals must have their fundamental moisture within them; how otherwise could they exist? Even the corporeal metals I do not exclude here, for their moisture preserves them in the fire. For when this moisture is separated from them, nothing remains but ashes — and he who has no ashes, he who cannot make ashes, will also not be able to make the regenerated salt.

Moses must have well understood this; for how else could he have burned the golden calf to ashes and given it to the children of Israel to drink?

This fatty moisture the philosophers call their incombustible Mercury, which cannot be consumed by fire, nor does it easily depart from its dwelling. Yet when it is driven out by violent and unnatural force, the more this moisture is denied, the less remains of the corporeal metal.

This can be seen in the smelting-houses, at the blast and melting furnaces: the fundamental moistures of the minerals, when expelled by such fierce force, vanish in a thick mercurial smoke and vapor up the chimney.

The smelters, however, claim that the vapors must be burned away; but in the end it is found that the content of the ore is very small.

Yet the attached smelter’s soot, which settles on the chimneys, shows itself to be very rich, though most of its moisture is already lost.

Reasonable philosophers, however, say that through proper instruments and suitable additions, these should be collected—those same soot-deposits which the smelters call “robbers”—for such are, as it were, the food of the metals. Whether and how such a thing might be possible, I have never attempted, and leave it to others.

This has given some occasion for further reflection, as they observed that from the collected smelter’s soot a portion of silver can still be extracted. Therefore, they have turned their attention to Arsenicum as their supposed right subject; how they have since experimented with it, the authors report.

Others, however, acknowledge that this cannot succeed, since the philosophers speak of a water which wets not the hands; and so they have worked with quicksilver, which they take for a metallic water. Yet this metal is of a nature far different from what superficial people imagine — as Herr von Welling clearly writes in his Opus Magia Cabalistica.

Although many have read this, few have understood it; and from this have arisen the Mercurialists, who deal always with Mercurius and yet know not what they mean thereby. For this volatile bird, whose origin they do not know, can neither be bound by them, nor held fast — even if they shut it in and melt their vessels, it escapes them nevertheless, and Mercurius remains their elusive object, which he seeks on high; yet its field is so vast that I shall not engage in such an investigation.

But as to how the philosophers proceed in drawing out their so-called quinta essentia, I wish to present my simple opinion, which I have discovered through the well-known art of brewing beer.

Here I set forth first, that all generative properties consist in an agens and a patiens, namely, a moist and a dry.

The brewer takes the grain as nature has produced it, moistens it with water (from which it too has sprung) — and this proceeds naturally, without any contradiction or opposition. The grain takes up the water, swells, and thus the kernel becomes slimy, being fitted for growth and multiplication.

But just as a seed cannot grow if it is overwhelmed with excessive water, so too the brewer immediately separates the excess moisture. When this has been done, the agens and patiens begin to act; the natural spirit — which one may call the inward fire — strives to free itself from its bonds and to exercise its powers.

Thus the grain begins to sprout and is able, in due time, to send forth a shoot. But the brewer will not wish to retain these powers, but rather turn them into a drink.

Now it depends upon the master himself whether he wishes to prepare a strong or a weak beverage. He may thus produce brandy, ale, or beer, and the like — from which even a small quantity shows more power and strength than if one were to consume a much larger portion of the raw fruit, which is known to all and easily judged.

Whence comes this strongly active spirit, that even a small amount can so inebriate a man that he seems bereft of all his senses, and from a single fruit so much and manifold scent and flavor is brought forth?

Moreover, it is to be marveled that where a great quantity of such a strong drink is produced, only a small portion of the original fruit is required, and that therein one perceives so little of the former taste or smell — from which, to speak in a purely chemical sense, the Quinta Essentia and purest essence has been drawn off, the coarse parts being separated in the lees and dregs.

But if now this strong drink were concentrated and closely united, so that much of it were brought together, it would no longer endure the fire; for one may observe in this expansion and multiplication reasonable manner in the vegetable kingdom.

But what a wondrous spirit must indeed rule in the mineral realm, when it is loosed from its bonds and kindled! Saltpeter may here serve us for reflection — though it is only a salt — what power it reveals, when prepared into gunpowder!

Although it cannot yet even be regarded as a mineral, it is transformed into a spirit, shatters and bursts apart, and dissolves the hardest metals into the finest dust.

For this reason, the sophists have conceived the thought of seeking the true Universal Menstruum — yet strife and contention arise, when such a water is united with metals. Experience has shown that such is not homogeneous with them, since after repeated distillations the formerly bright and beautiful metal is indeed reduced to dust, yet instead of a true dissolution, it returns, after some loss, to its previous fusion.

Thus the mineral spirit is merely awakened and inflamed by such a menstruum, rather than truly destroyed.

We see, accordingly, that the vegetable seed must be nourished and increased by its own homogeneous water nourishes the seed, not consuming or destroying it, but rather causing it to swell and thereby fitting it for growth and multiplication.

Thus minerals and metals must likewise necessarily have their own special water, which is as homogeneous to them as common water is to the vegetabilia. And from this, if a drink were prepared, it could well serve man for health, and many illnesses might thereby be healed, as the philosophers assert.

For since men require vegetables for their preservation, why should not minerals also be able to serve for health, which is why the universal medicine is so named?

Here the question might easily arise:

What actually is a Universal Medicine or Tincture?

A certain author answers such in this manner, and sets forth this mark: A universal medicine and tincture must consist of pure, concentrated fire and exalted life- and light-particles, which are in accord with the natural life of man, being of the same essence and nature. Otherwise it would never enter into the human body; for since life is nothing else than light, which chiefly depends upon the sun, disease, on the other hand, is nothing else than a particular privation or suppression of this natural life and light within the human body.

Therefore, the cure of sickness can be nothing other than the restoration of such deprived life-particles through a proper medicine.

But if, in the preparation of your medicine, you have driven away the life — which is most subtle and cannot endure any common fire — from your subject, or even utterly destroyed it through harsh and excessive means, with what will you then restore the loss in the patient and strengthen the weakened Archaeum?

For as soon as the external, administered heat is greater than the natural warmth of your subject in the work, so soon does the spiritus tingens evaporate with the moisture as life itself, and your labor has been in vain.

Although the philosophers write very obscurely and covertly concerning their universal mercurial water, yet they do indicate various menstrua. Basilius himself says in his second key, by way of parable, that upon those lees many and various beverages are to be found. He praises his juice from the unripe grapes, his spiritus vini, etc. Yet whoever would make use of these must also necessarily know his vineyard. Soon he praises his Spiritus Mercurii, so that an unlearned person might well become dizzy from his description, though such may not be half understood.

And just as secretly do they describe their various paths and the preservation of the mineral seed and its unfolding. Yet they set forth their work through figures, so as to prompt reflection. Thus they depict two serpents coiled together in a circle, biting one another’s tails, with the inscription “Rebis” above them.

By these two serpents they wish to represent the two substances in their work — namely, their water by the winged serpent, and by the creeping serpent their so-called Electrum Minerale, which Basilius Valentinus names under the symbol of antimony in his Triumph-Wagen des Antimonii.

However, he does not mean the common antimony thereby; and just as the brewer must first sprout his grain before he can unlock and awaken the natural spirit of the mineral, so too must they first vivify their Electrum, that their Chaos — as they call it — may be call it Chaos. Why they have chosen serpents as the symbol thereof, I do not know — perhaps they wish thereby to indicate the poisonous nature of the raw matter, or the caution that must be observed in the handling of this work.

With this Chaos they proceed in various ways, as they find suitable, and for this reason they seem, in their writings, often to contradict one another; yet they only seek thereby to veil their matter through many names.

Their Menstruum they call their Universal Mercurial Water, their Acetum, Aquafort, Quintum Essentiam Vini, or the sharpest vinegar of nature or Simplement-Essig, because it is said to be an acidum naturae sensu, drawn from the great sea of the world, and found among all minerals, being homogeneous with all metals and specified among the minerals.

Others name it the winged serpent. Basilius Valentinus calls it Spiritus Mercurii, because it proceeds from the Air-Mercury, from which we all, and all creatures, live, move, and breathe, and in which they are specified.

What folly, however, these designations have provoked among sophistic dreamers, I will not recount — one claims to have dew, another rainwater, so that so with thunder and lightning they would capture it. Others, however, wishing to be the wisest of all, have sought through wondrous machines to draw down this universal world-spirit from the air, and have endeavored to fetch this strange guest from India, who has likely already knocked at their own doors, as the philosophers write.

Their Materia or Stone, from which they derive their Chaos and Seed, they have also named with countless titles. Now they call it their Antimonium, Kobold, Bley-Erz, Antimonium Album, Saturnum, etc., but especially their Electrum Minerale Immaturrum Paracelsi, because it is said to contain the seed of all seven metals.

It is easy, however, to see that all these names do not denote the true matter, for the philosophers lay the greatest emphasis on those who can name the matter by its true name.

This matter is said likewise to come from a root with its mercurial water, and to be born therefrom.

If one would ask: What actually is this Seed?

So testify the philosophers, that such a seed is a vapor, mist, or air, prepared by nature from the four elements, and destined by it for the generation of the perfect metal — that is, gold — and endowed with its own implanted seed.

Yet this is often hindered by various accidents, so that such a seed cannot fully perfect itself into gold, and therefore lesser metals arise and grow from it.

The philosophers, moreover, sum up this entire art in these short words:

“Dissolve the hard by means of a warm vapor,

and make it hard again — this is the whole art.”

At the same time, they write that in this science one must first separate the light from the darkness, and herein imitate the highest Creator in His work of creation — though not making a new creation, as many would have it — for the seed and the growing, multiplying power has already been placed by God as the vital fire in nature.

And nature brings forth all things according to the order of the Most High, and what God has given to man, who has been set above all by the Lord, it therefore does not seem unbelievable that man might come to the aid of nature and thereby bring forth quicker and swifter effects.

We see this indeed in the vegetable kingdom: in gardens and greenhouses herbs and trees that otherwise would scarcely bear fruit in a hundred years — for example, the aloe, which scarcely grows a tenth part of what time it needs — yet are brought to fruit sooner. In the animal kingdom too it is already known that one can hatch eggs without the hen.

Why then should it be impossible for natural philosophers to do the same in the mineral kingdom?

It depends only on whether the metals and minerals truly grow. This needs little proof, for otherwise the verse of our Church would be easily refuted, which itself sings:

“Thou lettest ores grow in the earth, gold, silver, free tin, copper, lead, and all manner of metals.”

Everything that grows is subject to decay and has also its own seed, according to the declaration of the Most High (Genesis 1:11).

In the mineral kingdom many exceptions have been raised against this verse by contentious and disputatious spirits, which are not worth the trouble to refute for he who possesses too little knowledge will not be honored; but he who knows too much seldom has the wisdom to use it rightly, and builds his house like a spider — too fine, and fit for nothing.

That from this seed and from nature fire can be brought forth is attested by Job 28:5, where it is said:

“Fire is brought forth from the earth, and beneath it, the stones are turned into bread.”

I do not hope that anyone will be so foolish as to think that this fire could be confined within Mount Etna or Vesuvius, for no nourishment grows above, but only ashes and smoke arise. Yet that this fire or growing power cannot bring forth anything by itself alone is shown by Moses in the second chapter of Genesis, where, recounting the creation, he says that the earth had not yet brought forth grass or herbs — and why? Because God had not yet caused it to rain upon the earth.

He adds further:

“But there went up a mist from the earth, and watered the whole face of the ground.”

Thus the moisture must first awaken the seed.

This moisture or water is found in two forms in nature, as Moses testifies in Genesis 1:6, where it is said:

“And God said: Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters…”

…and verse 7: “Then God made the firmament, and divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament.”

The waters under the firmament are filled with desire and impulse, such that they yearn toward the waters above the firmament; therefore, they rise upward, which we call vapors of the earth. With equal delight and impulse, the Most High has endowed the waters above the firmament with attraction toward those below; therefore, they descend again, and unite with one another, like man and wife, and conceive, whereby a mist arises which conveys its fruitfulness to the earth. This mist is called the morning dew.

Of this mist Job also does not forget to speak, when he describes the wisdom of God in the aforementioned 28th chapter, verse 4, saying:

“A stream breaks forth from a rock; the waters are forgotten of the foot; they are dried up, they go away from men.”

By which nothing else is meant than the mist described by Moses; and the philosophers also wish their Mercurial Water to be understood thereby. However, everyone is free to hold his own opinion; I therefore only present my own simple view I set forth my simple opinion in advance. It would please me greatly if others had better and more thorough thoughts, and would lay them before me — and at the same time explain the 20th and 21st verses of the 1st chapter of the 2nd Book of the Maccabees, where it speaks of the holy fire which the children of Israel hid during their captivity. When they later sought it again, they found not fire, but a thick water, which nevertheless kindled the sacrifices — from which rightly arises the question:

What kind of fire is this, that with time resolves into water, and yet has kindled the sacrifices?

Hermogenes writes in his Spagyric and Philosophical Fountain (p. 2): “He who can demonstrate this secret source of wealth and of health in an occult manner, and who can elicit from our shining philosophical stone the wondrous magical fire without fire — he is a true philosopher.”

Thus, if such a thing is to be elicited without material fire, then necessarily a fiery water or watery fire must be required; and therefore all the laborants must be expected, who boil and roast the minerals and metals, and through their great smelting fire destroy the seed and drive away the spiritus tingens.

I could, with much writing, expand my briefly stated cases and many further reasons in such a manner that a much more substantial treatise would arise therefrom, if I had the inclination or had learned the art of disputation.

Yet there remains one particular objection — namely, that no one exists who, from the reality and certainty of this most noble science, has seen an evident proof. In old histories and books one indeed reads of various experiments, particularly of David Beuther at the Saxon court; but these are now read only as novels, and are mocked by the credulity of former times.

New temples (societies) have indeed shown themselves as if they were true philosophers and defenders of chemistry, yet none are known. I myself have given considerable effort for a long time to find a true philosopher — yet in vain.

On the other hand, men who, by their hypocrisy, have insinuated themselves as Grand Masters of the Rosicrucian Order bestowed and who wished to make as much silver and gold as is reported of Solomon, have become superfluously known to me.

But I ascribe no honor to these, rather I assign them, according to common usage, to the character of deceivers and rogues.

As to why no honest philosophers show themselves who would defend the honor of alchemy — on this I have my particular thoughts.

A certain treatise entitled The True and Perfect Preparation of the Philosophical Stone of the Brotherhood from the Order of the Golden and Rosy Cross, published in Breslau in the year 1770, writes on page 99: that in the year 1624 this Brotherhood consisted of only 9 masters and 2 apprentices, and that they were thereafter mindful to increase their Order up to 63 members.

Now, it could hardly be possible that such a small society, in so long a time, should have entirely perished — unless through certain misfortunes they have retreated to another part of the world.

Although new philosophical books do indeed appear, which are attributed to old authors, and are often marked with great authority — yet if one asks the publishers of these books about the author, they find him to be invisible — whereby the sophists betray themselves, who have learned this art of concealment exceedingly well, and who know how to vanish like the cat from Tauenzien; for true philosophers never conceal their proper names.

As may be seen in the old Adepti, such as Theophrastus Paracelsus, Basilius Valentinus, Count Bernhardus, Becher, and others of like kind, who, with their wonders and other experiments, proved their sciences, and served their neighbors.

But were these authors of the new writings true Adepts and Christians, as they boast themselves to be, they would also be better stewards of the natural mysteries, and would seek more disciples and successors, strengthen the weak, comfort the suffering and poor neighbors, bring them help, and glorify the omnipotence and miracles of God.

Yet those who truly love wisdom, and seek to behold the majesty of God in Nature as in a mirror, do not hide themselves — for love of one’s neighbor remains, and the saying of the Angel Raphael in the book of Tobit 12:8 stands firm:

“It is good to keep the counsel of kings and princes secret, but the works of God should be praised gloriously and made manifest.”

Could one truly regard such men as genuine Christians and Adepts?

Since, therefore, the Brotherhood of the Rosicrucians must have entirely vanished, and since no one now asserts the honor of alchemy while deceit has spread everywhere, it cannot be otherwise than that alchemy has become hateful to everyone — though both Nature and Holy Scripture contain traces thereof.

Yet these are only my casual and free thoughts, upon which others may reflect further or dispute without end.

End.