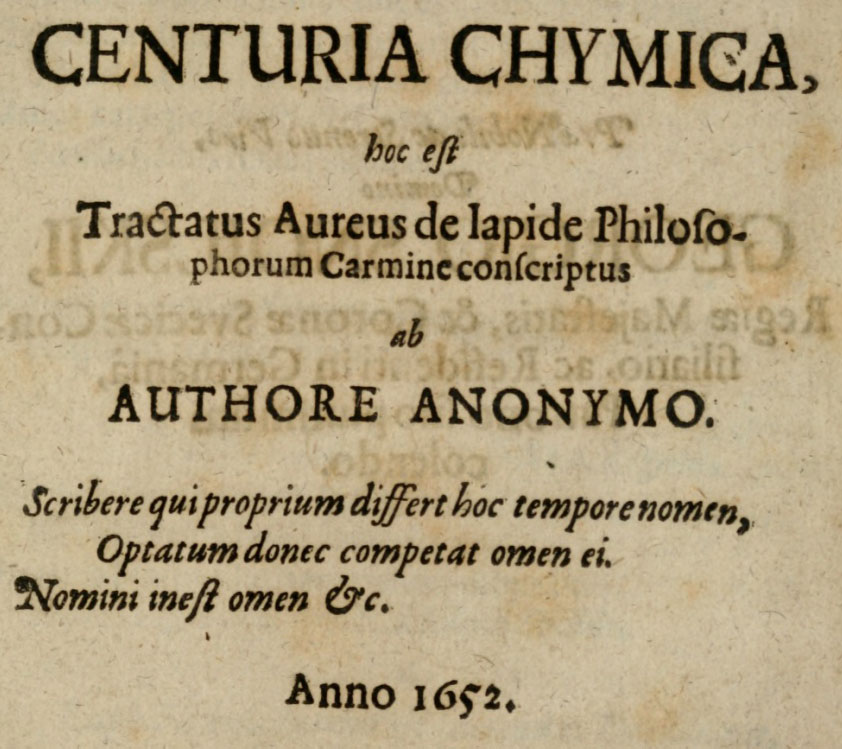

CENTURIA CHYMICA

This is

The Golden Treatise on the Philosopher’s Stone, written in verse,

by

An Anonymous Author.

He who refrains from writing his proper name at this time,

Will do so until the desired omen suits him.

The omen lies in the name, etc.

Year 1652.

Golden Treatise

The physicists write of this art only through riddles,

So that it may remain known only to their own sons.

The arcana are not to be cast before dogs,

Nor does the bright gem of the earth profit its unworthy possessor.

The books are witnesses of the art, they reveal the secrets,

But God alone, who guides the stars of heaven, reveals them.

6.

The chemists write only for their own sons.

The unlearned and the learned alike write poems everywhere,

Versifiers, but the chemists for their own offspring and for themselves.

They allow God to distribute His gifts,

Who tests the kidneys and hearts of all men.

7.

The chemist must be of steadfast mind.

Like a wheel on a chariot that rolls and wanders,

So the work of the chemist often tends to go.

For whatever aims high soon seeks the lower,

Whatever seeks the depths returns again to the heights.

The craftsmen of this art are wanderers, they pursue wandering things,

But the art desires to have steadfast men.

8.

In what place of the earth the material of the Philosopher’s Stone is to be sought.

The German land contains the golden fleece;

There is no need for you to penetrate the strait to Colchis.

9.

The material of the Philosopher’s Stone revealed through the Cabala.

Adam, the chemist, designates the material of the stone,

He, the first king in the whole world,

This the Almighty God created from red earth,

Which name in Hebrew signified Adam.

Great is the omen in the name, and its mystical appearance,

Which the Cabala of the Jews teaches as divine.

For the number of this name is sixteen times ten,

And from the sacred code it can be known.

For in the span of that time it was built,

Once in Jerusalem as the second holy house.

Mercury together with the number of the Sun reveals it to you,

Know how to rightly place the names and letters.

Sixty and six with six hundred make the order,

In numbers it can signify the same.

10.

There is only one material of the Philosopher’s Stone.

The stone is one, and the metallic medicine only,

One alone; apart from it none is given to you.

Nothing foreign is added to it, nor is anything taken from it,

Except a few superfluities besides its own.

11.

The material of the Philosophers is manifold in different respects.

The materials are one, two, three, four, and five;

Five, but one alone, true and sufficient for you.

There are two: one remains here, the other flies upward,

There are three together — salt, sulphur, and mercury.

You also have four elements — fire and air,

Which you may seek beneath the waters; thus earth remains to you.

After the Fifth Essence, offering you metallic medicines,

Follow likewise all the rest which you possess.

12.

The material of the Philosopher’s Stone is conceived only by faith.

The material of the alchemists’ gold is as far removed from common gold

As the earth is from the polished heavens.

Therefore, faith is required for those who discern only the outer,

Until they come to know the inner as well.

13.

Sendivogius adds an example.

If you place several infants together, hidden beneath a garment,

You cannot discern their sex by the light alone.

When the garments are removed, boys are distinguished from girls;

The difference is easily recognized by the light.

For the common eye perceives the forms of things in one way,

And the learned doctor in his art, in another.

Through the mirror of nature we see only the shadow,

And beneath this the greatest virtue lies concealed.

14.

The sum of the whole art, from Hermes Trismegistus, the first inventor.

The lower is made equal to its higher,

The same are of the sun, the same are of the heavens.

Swift Mercury, the fire sunk in the earth,

By your skill and dexterity of mind,

The spirit from earth climbs above the bright aether,

From heaven falls again, and seeks the depths.

Mercury governs both the earth and the sky with his scepter,

Once the feather has been taken for himself.

And the head and tail have been joined over the fire,

So that the redness enclosed may seek the outward parts.

All that he touches, he turns to golden yellow:

These are the mystical gifts of alchemy, the teachings of the art.

15.

The sum of the whole art from Geber, King of the Spaniards.

No chemical sulphur avails in the art of alchemy

If the pure bride be lacking to the bed.

For the bodies of metals are corrupted by any body,

But beware of taking it without a master’s guidance.

It is not the body itself, but the hidden virtue of the body

That will be to the alchemist like the nature of a woman;

For the male alone cannot produce offspring

Unless the wife brings aid to the husband.

The conceived seed is nourished in the womb of the mother

Until in due time the offspring is perfect.

From there the growth proceeds, nourished with the mother’s milk,

Until at last the limbs become strong and firm.

And so, these three things being present in themselves,

They provide to the alchemist the threefold medicine of the art.

16.

The Philosophical Egg of the Phoenix.

The egg of the phoenix consists of shell, yolk, and white,

An egg which the alchemists are accustomed to hide.

The shell signifies the Sun, the whiteness the Moon, the yellow yolk

Mercury—these are the three principles of the Stone.

The white is heated by the outer shell, in the likeness of sulphur,

The bird never entering its inner part at once.

The white itself designates the flesh and the bones,

The yellow, by Mercury, will be like the blood.

17.

The Philosophical Phoenix.

The wandering Mercury, the golden Sun, the shining Moon—

These are the ores of the Stone, of Mars, and of art’s aid.

The material of the Stone of the Physicists Hermes supplies to you;

It will itself in forming be the noble Sulphur.

The entire substance of sulphur does not benefit the Stone;

Hermes rejoices in the golden seed, exulting,

This seed alone the wife of Tithonus draws forth,

And in her womb she herself long cooks it.

When the seeds are long cooked, Hermes stealthily takes them together,

She conceives, and thereafter gives birth to the Hermaphrodite.

Terrible Hermes, because of his thefts, is put to death,

And placed on the pyre, he is turned into ashes.

The golden ashes are cast into the salty waves,

Hence is born the Phoenix, always the single bird.

This bird restores, nourishes, and of itself again sows,

And always builds its nest in the fire.

This is able to drive away all the diseases of men,

This raises the languid members of metals.

18.

The material of the Philosopher’s Stone is sought from the sea.

The matter, water, the prime well-mixed of metals,

A terrestrial fluid, is so called by the Physicists.

And the two elements of ore are present in all these,

Yet the rest lie hidden, paired, in secret.

The ocean is said to be the mother of all waters;

For from here they come, and to here they all return together.

The ocean itself abounds thus for the alchemist in these two,

The fishes, which the subtle right hand of the Physicist captures.

Here is the fierce whale, otherwise called Leviathan,

Scaly, devouring all things that it seizes with open mouth.

And in the place of wife the whale supports the husband Leviathan,

When they are accustomed to unite in due manner.

A dreadful sea monster is born from mingled seed,

Whose scales are entirely golden.

The sperm of the whale is a wholesome medicine for metals,

And is accustomed to drive away even leprosy.

No more words are needed, for it is wont to restore

The weakened members of the human body.

19.

The material of the Philosopher’s Stone is taken from insects.

There is a mighty salamander, unharmed by flames,

Known in the chemical realm to all sufficiently.

The bird that pursues it has deer’s horns,

It will not be a goat, nor a ram, but a scarab.

20.

The material of the Physicists’ Stone is compared to beasts.

In the chemical forests it wanders with many howls,

The prince of quadrupeds, a triple-bodied beast,

Its body is that of an elk, but the mind of a fierce elephant,

And it bears the horn of the wild rhinoceros.

Whether it be a rhinoceros, the skill of the Physicist inquires;

Who doubts, let him believe the Magi that there are two present.

21.

The material of the Philosopher’s Stone is likened to what is contained in the Ark of the Covenant.

The tables of Hermes, the manna also, and the rod,

The Ark of the Covenant of Mercury, of the chemical pact, holds.

This emerald tablet shows the laws in the art,

Teaches measure, number, weight, and likewise time.

By Jupiter, Saturn was driven from his kingdom in Olympus;

He carried with him the manna, which the ark holds.

It is said that once the rod of Aaron became green,

Believe it to be Mercury’s, the dry staff flourishes.

He who wishes to bear the Ark, let him himself be a Levite,

Lest he wish to have sustained avenging hands.

22.

The Ornament of the Chemist’s Tabernacle

It is said that once the rod of Aaron,

Belonging to Mercury, became green, though dry.

If the Levite himself wishes to bear the Ark,

Let him sustain it with avenging hands.

The Chemist-Levite, clothed in sacred vestments,

Approaches the work with seven lamps, and with all the metals, I think.

Let not pure and clear oil be lacking in the lamps,

So that the perpetual light may be maintained.

Let the Chemist-Levite wear the sacred garment,

Whose breastplate bears the engraved capsule of Urim and Thummim.

I have indeed said many things to the wise and skilled;

He who has begun well has half the art.

Fire and Azoth are sufficient, as fire is denoted;

Thummim is accustomed to signify justice.

23.

The Matter of the Physical Stone Taken from the New Testament

Gold, frankincense, and myrrh the people, even the Magi,

Offered to Christ; frankincense belongs to the Moon, myrrh to Mercury.

Here it conceives flames, and both burn separately;

No violent force harms them when joined together.

24.

Things Chiefly to Be Considered in the Philosopher-Chemist

In the metals, the nearer way is through salts;

The secret of the art and the salts will provide the virtues.

For whoever does not render brittle glass or ductile glass to himself,

No place will be given to him in the chemical art;

And likewise, he who does not know how to lead waters from the living stone,

No place will be given to him in the chemical art.

He who does not know how to fix the volatile

Shall have no place in the art of chemistry.

But he who holds these things together, and teaches by his own skill and practice,

Shall have in chemistry the first place in the art.

25.

The matter of the Philosopher’s Stone has countless names.

If there is any trust to be given to the books of the chemists,

The old man himself with the sword requires it.

Without this you will accomplish nothing of true worth in our art.

Here it closes and opens, it brings to life and it kills;

Our arsenic, if anyone calls it by that name,

Holds entirely the mind of Geber.

If you call it panacea or theriac,

You will then be an imitator of the sect of Hermes.

As many as the bright stars are in the whole heaven by night,

So many are the names of our matter.

And unless our names were multiplied,

The matter would be a game for boys.

26.

The Philosopher’s Stone derives its origin solely from vitriol.

“In vitriol is whatever the wise seek,”

The old rule of the art is true as well.

Vitriol is triple green, which must rightly be noted,

Of Mercury, Moon, and Sun likewise it is green.

Whatever it produces will flourish, the green color itself;

It is the life of plants and trees alike.

In the month of May, I ask you, look upon the whole earth,

Whatever you see in the light is all green.

So also will ours flourish, believe me, vitriol-born,

Mercury himself, winged, will stand on his own wings.

Thus also our green Lion flourishes when it is slain,

Then likewise and entirely the shining Moon grows green.

This is the color intermediate between red and white for the artist,

But concerning the matter and the color, enough has been said.

27.

Faith, Hope, Charity, to be considered in the philosophical work.

The sole hope of the chemist rests in yellow gold,

Yet more often in vain, he is deceived by his own art.

That which he has, he loses; what he hopes and desires, he lets go,

The appearances of brass depart, and the shadow remains.

He trusts in books, yet the books distrust him,

Often they are wont, in vain, to be mistaken in their trust.

Dear love of faith through byways frequently wanders,

Here again he shows the just path to enter.

28.

The materials of the Philosopher’s Stone, from which they are taken, according to Sendivogius.

Saturn to the Moon, Venus to Mars, and Mercury;

Jupiter, in chemistry, perform mingled duties.

For they are equally distant from the source of heat,

Which the Sun imparts with its own light to each.

Sublime bodies only are amended by the Sun,

Take these prudently, leave the rest aside.

29.

Morienus on the three principles of the physical stone.

With white smoke, the green Lion, and the foul water,

These suffice for the chemist; all other things avoid.

30.

Epilogue.

Or here, if anywhere, it will never be granted you to know more than this:

— The seeds which Corydon sows, those shall he reap.

Whoever sows metals, shall likewise reap metals in due time;

As is your seed, so shall your harvest be.

31.

The efficacy of the Philosopher’s Stone.

Alas! how hard the condition of life presses upon the wretched,

Whether he is afflicted by disease, or at once by the air, the miserable man.

The true preparation of our Stone brings help to these,

And utterly cures both evils at the same time.

32.

On the interchange of the four elements.

From earth comes water, from there air, afterwards leaps forth fire;

Yet a single sphere contains the latter two.

For they are wont to lie hidden in water, both fire and air together,

And at last into earth all things fall back, each to its own.

33.

Rosarius, on Earth.

The earth is the rest of spirits, and when compacted,

The hot flame never again harms it further.

34.

On Water.

The soil is perfected, which the crowd of sages sought,

— The art, through waters in waters, because of waters in waters.

35.

Sendivogius, Treatise on Fire.

Fire is of twofold kind; the first subsists by itself,

And encloses its own material here in its very bosom.

But another will provide you with natural flames,

He fixes the material, digests it, and cooks it with fire.

36.

Likewise concerning Air.

Of the four elements, the first and noblest:

Of all things, the living mother is water.

Over this itself was borne the divine and gracious Spirit,

As Moses himself, the priest, has handed down.

The Spirit is liquid fire, which stirs the waves,

Air thus having arisen, draws along all created things.

37.

A miracle in making the Philosopher’s Stone, worthy of note.

Learn how to draw living streams from stone,

If you wish to know the magistery of the Alchemist.

But if you bring nothing to the stone, unhappy, dull-witted one,

The art of Chemistry teaches many mystical mysteries;

It is credible to the vulgar only when the eye grows dim.

Yet this work of art remains true and lasting.

Look upon the very hard flints, rich in gold,

And the clods — you see many of nature’s marvelous wonders.

38.

The virtues of Arsenic.

White arsenic destroys for you the body of gold,

And reduces it entirely to black ashes.

Here nature plays — beware lest she play with you herself;

This jest of wit will be for you no jest but death.

The scorpion itself kills only with its venomous sting,

That which arsenic also achieves with its own odor.

39.

Theophrastus on the same.

Arsenic offers us a white tincture,

Which you behold in whitened new bronze.

40.

Sendivogius, Treatise XI, on Saturn.

When our old man devours silver and gold,

Our art gives his languid limbs to the fire.

And it cooks the ashes, rich in gold, in boiling waves;

From this arises health, and hence a medicine for leprosy.

41.

On Calcination.

That which you wish to dissolve, first you will make lime from the body,

By caustic means, so that water may more easily dissolve it.

42.

On Solution in General.

That bodies may be better united, dissolve them,

And drive out both the seed and what is enclosed within.

43.

On the Solution of Gold.

Neither by strong waters nor by the King’s water is gold dissolved,

But you must seek a single material,

Which provident nature has created for our use.

This, when melted, dissolves whatever metals you have.

If our material is joined with your gold,

It will melt, like snow dripping away into water.

44.

Raymundus Lullius on the furnace, vessel, and fire.

Let the Artist have a single furnace, two little vessels,

Lime, and horse dung, for these will produce the fire.

45.

The same, on decoction.

To dissolve, to sublime, to pour forth the coagulated, to cook what is cooked,

Such are the works of the chemist of Mars and of the art.

46.

On the smell of the material, Morienus.

At first the material spreads an unpleasant odor,

For it is often likened to corpses.

But when the labors of Tartarus have ceased,

Scarcely will there be any smell more pleasant than ours.

47.

The same, on touch.

The material is soft to the touch, and greater still is that softness

Which lies hidden in its own body.

48.

Arnold on weight.

If the weight of snowy Sulphur be one,

Let the weight of your ferment be three parts mixed.

49.

Separation.

The heavy earth seeks again the bottom, the other three ascend;

The air, if it also be dissolved together,

Unless you dissolve it, the fourth will follow those going forth.

The fire-bearing flame presses the three companions.

50.

On colors, Theophrastus.

From one root there springs forth whiteness, redness, and yellowness;

Rhases — but here the ferments are wont to vary in two ways.

51.

On the many colors in the work of the Philosophers.

The first color of our material is blackness itself,

Which, when putrefied, it offers to its craftsman.

If it does not become black within forty days,

Then the raven falls by his own hand.

A white bird gradually succeeds it,

And here it sings for itself a funeral song.

If you hear this song, believe me, you are certain in the art;

No one outside the chemist perceives this melody.

About this harmony there is much talk among all

Who hand down the learned doctrines of chemistry.

Chlorion follows the swan, after this comes the bee-eater,

It flies forth, and a little later the robin appears.

This bird fears no hawks nor dreads the falconer,

Just as the Phoenix weaves its nest in its own fire.

52.

The Chemical Pandects on colors.

The first color of the material is black, but the second is white,

The third color itself will be like the likeness of blood.

53.

Hermes on colors.

There is some green color, yet one seeks the redness;

White and black are held in equal honor.

54.

On weight and measure.

The weight belongs to cold, the measure to heat,

The moist with the dry completely seek each other.

55.

On salts.

The beginning of the chemical art is the fusible salt,

It does not allow the craftsman’s hands to be moist.

Gold-bearing sulfur, and likewise solidified metals,

Are said to dissolve the material into its first form.

Sulfur burns the wings of Mercury, so that willingly,

It may have a safe place in the flame.

Fixed Mercury can dye red into gold

The bodies of metals which are accustomed to be fused.

56.

Avicenna.

Salt is the root of the work, the middle salt, and likewise the end;

Salt dissolves both sulfur and mercury together.

57.

Salt of Urine.

The salt which is in urine joins two bodies for you;

Whoever lacks this salt should take Armenian salt.

58.

Common Salt.

Common salt prevents any body from putrefying,

Except for the parts of our magistery.

59.

On Alembrot Salt.

Salt of wine, oak, stones, nitre, and the sea;

Reverently keep these kinds of fossil salt.

Addition.

Add virgin honey to these, and fusible fat;

Mercury binds your prepared fetters.

Nature.

Stay far away from this foul filth with vile dung,

Or our Apollo will give you the product.

The Craftsman.

I think manna of the sword-bearer, mixed with its sediment,

Which Mercury often is accustomed to color.

Nature.

What good is coloring? You all seek the tincture

Which my own Hermes alone possesses.

If you add anything foreign to it, you will never take anything away,

Except for the dregs which he holds together with it.

60.

On Sulphur.

Take the golden seed, the body neglected,

For the bulk of the body greatly harms it.

Everything it touches it shatters — mineral bodies —

The same seed restores them, and the redness itself.

61.

On Form and Matter.

Any matter eagerly seeks to receive the very form,

Just as a woman seeks her own man.

62.

On Mercury.

Mercury consists of subtle and white earth,

And again of clear water together with sulphurous.

63.

On the First Matter.

The first matter is twofold: the nearer and the farther,

The nearer is Mercury, and the farther is liquid.

64.

On the Mortification of Mercury.

Two kill Mercury, joined together in a pact,

And the wife takes the place of the man, the man of the wife.

The mortification of Mercury is easy, but into vapors;

That it should rise again is a difficult labor.

65.

Mercury is poisonous.

Living mercury is accustomed to be a dreadful poison,

If taken in, it immediately harms the liver.

66.

Hermes on Mercury.

Our mercury is nothing but turbid air,

Which the wind of chemical art has lifted up.

67.

Various operations of Mercury.

Mercury dissolves and coagulates itself,

It betroths itself, and is accustomed to fix itself.

The venomous one kills each and every thing with its poison

Until it meets its sad fate.

After death it offers its most excellent medicines,

Especially when it glows with redness.

68.

Theophrastus on Mercury.

Mercury is nothing but pure metallic foam,

Which, by the power of its sulphur, seeks high things.

With wings cut off, the dragons return to their closed lairs,

Then they rejoice to dwell in a terrestrial place.

69.

The preparation of Mercury.

Living mercury is harmful, but revived it is loved;

When its blood is retained, give the rest to the fire.

Tartarus, Hell, the realms subject to Pluto —

These changes the pyre is able to endure.

When the body pays the deserved punishments for its crime,

The soul willingly joins itself rightly to its own.

This soul—wonderful to say—rejoices with its own body,

Which no one can join to a foreign one.

When both are joined together, the body is glorified,

Which the physicians seek with great diligence.

70.

Revived Mercury

At last it becomes revived by the tenfold power of men,

The hermaphrodite, dead from evils and wounds.

If you do not know men, nothing is if you learn the rest;

As many precepts of God, so many of the art will there be.

71.

Hermaphrodite Mercury

The hermaphrodite gives birth, and the woman in childbed herself is delivered after one and a half months—

This is the time you must rightly mark.

For unless you observe the puerperium according to proper custom,

Your hope and labor will be entirely in vain.

Whereby the limbs of the contracted body are restored,

Let there be baths for drinking, salted broths, food.

Then again the fertile womb is handed back to the parent,

So that it may multiply its offspring.

It conceives without a man, afterwards only from an image,

Becomes pregnant, and thus the chaste virgin gives birth.

72.

Of the golden and silver tincture

The Sun gives solar colors, the Moon lunar colors,

And arsenic here plays the part of each.

73.

On the triple stone

There are three stones and likewise three salts, from which, by art,

All of our magistery has been completed.

Mercury is triple: the first calcines, the second sublimates,

The third, as a companion, makes these manifest.

There are also three waters—of the Sun, the Moon, and Mercury—

Which are only fluid for the sake of the first water.

74. The Sound of the Trumpet

Silver also is given as living, in double danger;

This body prepares it, and also dyes it the same.

75. On Projection and Multiplication

Lullius, in the Elucidarium, chap. 6

To tinge, to multiply, is the reciprocal order of works;

For, one being placed, the other is not far away.

Hence constant Phoebus gives you Cynthia’s light,

Without which no one can tinge perfectly.

Mother Moon of the sea stirs the salty waves,

Then together embraces the work begun with happy omen.

Salt is seasoning to man and also to metals;

In chemistry there are perhaps very many kinds of salt.

Salt destroys and combines, separates and equalizes,

Because floating minerals are perhaps also a kind of salt.

Mercury, thirsty neighbor and inhabitant of the Moon,

Seeks also the aid of salt and of the Sun.

When this is seized, it is fixed, and immersed in the dyed waters,

Until at last the red crown is given.

These four things it graciously shares with its nourished offspring,

Thus their progeny will always be very many.

76.

The difference between common Mercury and the Philosophers’.

The marvelous little monster Mercury flees the fire,

Though in truth it is nothing but fierce flame.

For it burns like sulphur if fire presses it,

But the little flame of common mercury holds nothing.

77.

Raymund Lull in the Testament.

Three stones of chemistry: the first will be vegetable, the second animal,

After this, the third will be mineral.

78.

On the golden and silver tincture.

Phoebus, with your redness, Cynthia clothes herself in white,

Yet from here she produces offspring unlike herself.

This is the reason why you can conquer Cynthia, Phoebus:

The same color is given to the mother from this source.

For Phoebus never dyes unless with red dew

Mercury has been sprinkled to its very depths.

79.

On the time of the work.

Cynthia with Phoebus begets a precious stone,

But both delight in a long delay of time.

80.

On projection.

Await the birth, if you see the earth herself pregnant;

Feed the newborn joyfully with a small morsel.

Until, being made fluid, it endures the violent fire,

Then cast your elixir upon the molten metals.

81.

On the time, John Isaac

From Phoebus and Luna the whole art can be prepared,

In a long time, yet still without fear.

82.

Fire and Azoth suffice

There is one foot which bipeds and tripeds take,

Let them commend it, and so there will be one fire.

83.

Avicenna, on the dissolution of matter

The stone never bears fruit until it has subsided into nothing,

So that it may be entirely like water, or like oil.

84.

Bernard of Treviso, Count, on weight

The weight of Mercury’s sulphur will balance itself to you,

Whose weight in comparison can in no way be lacking.

85.

On the triple stone

In three things the constant perfection of all matters is contained,

Which are Salt, Sulphur, and Mercury together.

86.

What Mercury is

Mercury is nothing but the tail and head of the dragon,

Which equally holds the power of Venus and of Jupiter.

For the fixed one is the color of Venus, the other flees from Jupiter,

The whole body being of a grayish hue.

And the head is compared to the heavens, and the tail to the earth,

And by threefold measure it is more polished, alone.

The head is bloody, containing flesh and bone; the tail

And the head is male, the tail remains female.

The head seeks the heights, but the tail lies down below,

And thus the tail lies unmoved, while the head stirs.

This is the ultimate, most perfect sum of the whole art,

That you should join the tail to its head by art.

87.

On the solution and separation of the philosophical matter

Whoever wishes to divide Mercury must also dissolve it;

This labor is difficult, yet here it is easy.

To the experienced, the work is believed to be easy, and to the skilled,

But to the ignorant it entirely vanishes from the fire into glass.

For Hermes is nothing but smoke, unless it is compacted

By the force of sulphur and of salt.

88.

On the uncertainty of time in the philosophical work

No exact time is given, nor month, nor day,

For this work, as you can count countless causes.

For place and fire are wont to alter the time for you,

Thus glass, vessels, and the lot of frequent labor.

There is one who counts three years, another two years,

But others are accustomed to count months.

Just as we see the births of men vary,

So our art’s work can thus vary.

89.

Mercury is compared to the pelican and to the serpent

Just as the pelican draws blood from its own beak’s point

And with this is accustomed to revive its chicks,

So the blood of our Mercury, thus rightly prepared,

Can revive the dissected body.

It has the nature of the serpent, and again unites with itself;

Although it is cut apart, it returns better.

90.

On the various methods of projection, from Raymundus Lullius and Blasius Penotus of Portus Aquitanus

Hermes casts the head to the tail, well fused;

But Lullius thinks otherwise in chemistry.

You will cast the foundation upon one or the other,

Thus the abundance of material will be greater.

Hence the more volatile is restrained by bonds,

In another’s house, in seats and places not its own.

For its own home is scarcely considered natural,

And often it needs much labor from you.

If a man wishes to beget, he does not sow

Into his own body, but into that which is similar to it.

91.

That the art of chrysopoeia is rarely understood from mute books, but mostly from a living teacher

In chemistry, the masters made few books,

One having learned from another by word and by hand.

Lullius admits that he began with Arnold as his teacher,

And that he followed the path to the chemical arts.

Angelic Thomas had the name of Doctor,

Famous in all the world for his learning.

Albert the Great is held as his teacher;

From him he had drawn the celebrated riches of the chemical art.

Morienus the Warm had laid open the whole art,

Though to the ignorant it still remains hidden enough.

And Theophrastus once taught Trismegistus,

And Haly, king of the Arabs, likewise taught Morienus.

I could spend whole days writing down

The names of the authors of chemistry,

Who today transmit the chemical arts in full;

Yet, though hindered by criticism,

They have nonetheless lost none of their diligence.

They could never have learned these things by their own guidance,

Had they not lived, holy Noah, your years.

92.

That the Philosophical Secret Should Not Be Revealed

Whoever reveals the secret to companions or others,

No one can live safe from treachery.

Let Sendivogius be for us an example,

For he once fell into the hands of the people of Wiln.

He who had taken rich spoils paid the penalty for his crime;

Fastened to the cross, he bore the sad burden.

Of this deed the people of Württemberg are still witnesses,

And the inscription on the cross will be a witness’ title.

Theobald also recounts many examples to us,

Likewise Bragadino, and of a certain Monk.

Whoever wishes may freely observe in his own mind or in any book;

He who is wise will be cautious from another’s crime.

93.

To Whom the Knowledge of the Philosopher’s Stone is Given, from the Opinion of Aurelius Augurellus, Book 1, Poem 2

Let no deceitful, unjust fraudster practice alchemy,

Who deceives others with false appearances.

Let no idler or mere tinkerer approach,

Nor one who lives under a base condition.

Let the citizen devoted to the city stay far away from here;

Let him not seek gain from goods brought from others.

Let not the greedy merchant pollute the work,

Who before all things measures wealth by coin.

The art hates ignorant farmers and mechanics,

And those who wish to seek many riches,

And those who, having followed the most learned camp of the Muses,

Think themselves worthy of the name of sage — do you think so?

Do you think this crown to be the merit of physicians,

Who have never destroyed books nor betrayed physic?

Do you think that Jehovah grants the greatest blessings to the highest,

If they are not worthy, not enough in merit?

The gold-bearing stone invites only the wise,

And those who worship God with true religion.

He who wishes to see many hidden things of nature,

Let him apply himself here, and read what is written.

94.

How much the administration of the Philosopher’s Stone may avail in the human body, according to the mind of Aurelius Augurellus, Hortolanus

This divine medicine can drive away old age,

Which by itself is present as the likeness of the whole disease.

It “separates and overcomes the base, and renews the decayed.”

By tempering it, the gold-bearing stone provides what is excellent,

And often arouses innate strength,

Driving diseases wholly far away from there.

And long preserves the bloom of youth in shining brightness,

Displaying wonders in the human body at the same time.

It dries what is moist, moistens what is dry,

Warms the cold, and cools the hot.

If disease had lasted a hundred years in whole,

This time the cure would give the measure of the Moon’s month:

Half the disease, half the cure.

The time is given, if one has believed the chemists,

Three days, seven years, but one year alone

Is asked for one cure, one day itself is required.

95.

That a philosopher can speak without the harm of another, according to the mind of Aurelius Augurellus, book 1

He who desires too much to speak of another’s harm

Will bear many losses, and conceal even more harms.

Yet without harm, he seems richer,

Who gathers riches without deceit,

Who prudently draws from his own, without fraud or trickery,

Whether he seeks silver, or even gold itself,

“Yearly it may exceed a hundredfold what the scales can measure,

With small expense, without delay of time.”

Heaven itself grants this gain to the possessors,

So that no one could rightfully hide it through theft.

NB. Here the anonymous author ceases;

To complete the Centuria, it pleased me to add from the Chrysopoeia of Aurelius Augurellus the following verses in heroic meter.

96.

On the multiplication of the Philosopher’s Stone, from Aurelius Augurellus, Book 3

Here I will not speak of fictions, but of what must be handled,

And I will set forth, though long veiled in obscure figures,

Those things which certain craftsmen themselves confess they have hidden,

Deliberately, as if by the commands of an ancient Sibyl.

Therefore, prudent one, do not yield at the final stage,

For it is brief and of the least art, but of the greatest use.

First of all, mix it with yellow metal,

The prepared medicine, and blessed with it,

You will soon see the power to bear itself forth.

Or, when the pure seed is again joined with gold,

It is not hard, and with much you will draw forth by this art.

The method for those things which we long ago required is set forth,

Enough having been expressed, for not everything can be done equally.

Of this purple powder, take a part and quickly

Mix with the rest, and kindle them with gentle heat,

Boiling together the mingled mass for months,

Until in due time the whole succession of colors appears,

Which you may behold, as one marveling at three years in a single year.

You will see, and soon you will gather the greatest sums

Which you have long sought with diligent art:

And you will do this again and again, as often as it is completed,

So often will its powers and the powder itself be renewed;

You will strike out a heap of powder—for the swifter it is,

It grows, and from here it gains more while retaining the former strength.

It grows while it is growing, nor is it vain to believe this,

Since it is sometimes said by ancient authors,

That by casting but a small portion into the waves

Of the sea, the whole silver there would become quick,

And the vast ocean could be turned into gold,

So that Neptune above all gods would be the richest,

And the Nereids would play in golden couches;

Moreover, drying their hair in the pure sun,

They would be sky-blue, a hue no other color more fitting to gold,

Which adheres to it, and to the ethereal, to which gold fully belongs.

97.

On maintaining silence in the Philosophical Work because of the dangers involved

The same author, Book 1

This above all I warn again and again at the outset:

Lest the grace granted to you from Heaven should be snatched away—

(For no one has hoped to receive it from elsewhere)—

Do not even hint it to a dear and trusted friend,

Still less tell others, nor boast as if you know.

Whatever you learn, keep it truly locked in your heart;

Ponder it with yourself alone, and unfold the secrets only within.

And a little later:

For he whom prudence does not forbid to speak of these matters,

Will find that what was once his own will harm him when uttered.

Safe from treacheries is he who, through virtue,

Could prefer to hide himself in poverty,

Possessing great riches in a small coffer—

Riches by which kings rise in every place,

And wealth and abundance yield to his power.

All things, as if they were theirs alone, and lesser things besides—

If anyone has already been able to amass such great treasures,

Let him marvelously preserve them under the friendly guard of silence;

Which you also will do, and so forth.

98.

On maintaining silence in the Philosophical Work because of the false alchemists

The same author, ibid., Book 2

The art itself is suspect to the honest and hateful to many,

And it makes even its practitioners hated by others.

For so many liars wander about everywhere,

Promising many vain things, which they themselves never began;

Nor have they received, nor is it easy for them to know them.

Those who follow the right path that leads us stray entirely away.

Indeed, I have seen many eminent men and other learned ones

Handle and esteem all these things greatly;

Whatever the ignorant and base crowd approves,

What?—the great multitude derides all things;

Craftsmen, as if it concerned neither them nor others,

Weigh all alike in the same scale of judgment.

99.

On the vain labors of false chemists

The same author, Book 2

Why should I recall the sulphurs worn away by long toil,

And the nitres, and the purified salts, and the burnt substances of Lyæus?

Or the long-burning torches, or the inks on heated coals,

When kindled they pour forth drops from the reddened vessel?

These dissolve, repeat their cycles, and often resolve again;

Then they wash, grind them again, and next attempt to fix them.

They also turn them into lime, and by sending in vapor

They carry up into sublimation the breath of a light body;

You may see the assembled furnaces built by this rule,

And countless glass vessels coated equally with clay.

And those things which the silversmith turns to his own use,

And other sordid crafts, whatever skills are in the workshop,

They have seized upon for their own concerns,

And have enslaved themselves to their own mad labors.

Thus they always smell of sulphur,

Always have faces stained with soot,

And from the beginning they mimic hideous phantoms.

100.

On the pitiable and useless effect and benefit of false chemists

Nor could you truthfully call any craft more wretched

Than that which, under the outward words of Alchemy,

Is said to hide itself in obscurities, wandering in ambiguities,

Leading astray by devious ways those who follow its evil course,

Until at last it casts them forth into blind chasms,

So that you may sometimes see citizens selling

Their good estates, their ancestral homes, and stored goods,

Frequenting furnaces, and with bellows trying to catch

The breath of air, and to turn thin smoke (a crime!) into

Some substance, while the madman seeks doubtful wealth,

His inheritance—

Meanwhile his most sorrowful wife prolongs

A difficult life, their friends weep,

And the man himself becomes filthy,

His wealth washed away, his shame laid bare,

And he becomes a plaything and a tale for the crowd.

The outcome proves it—no wise man ever pursues such things.