The charitable guide extends his hand to the curious of alchemy to deliver them from this troublesome labyrinth, in which they are ever wandering and straying, wherein the Secret of the Art is enclosed, and which is explained throughout this book

Listen Audio Book Buy me CoffeeThe charitable guide extends his hand to the curious of alchemy to deliver them from this troublesome labyrinth, in which they are ever wandering and straying, wherein the Secret of the Art is enclosed, and which is explained throughout this book.

February 1884

Transcribed and translated from hand written French to English:

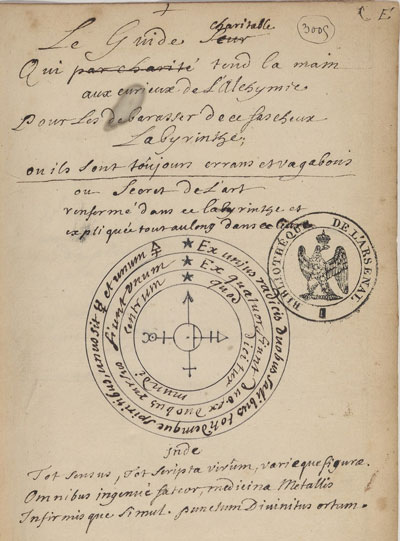

Le guide charitable qui tend la main aux curieux de l'alchimie pour les débarrasser de ce fâcheux labyrinthe, où ils - Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal. Ms- 3005

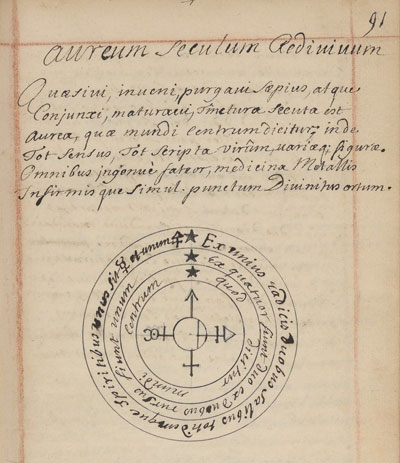

The author of this manuscript states in his dedicatory epistle to the Regent that he worked based on Mynsicht. This German author produced two works, namely the Thesaurus Medico-Chimicus, printed in Lübeck in 1638, and the Testamentum Aureum, printed in 1664. One may also include the Aureum Saeculum Redivivum, printed under the name of Madathanus and included in the Museum Hermeticum. It is from all these works that the author of this manuscript drew his own; he even copied the last two here. It appears that he was chiefly devoted to the Universal Medicine.

Latin:

Ex unius radicis duobus salibus, totidemque spiritibus, unus fit mercuri et unum sulphur:

Ex quatuor fiunt duo, ex duobus rursus fit UNUM,

Quod dicitur mundi CENTRUM

English translation:

From the two salts and as many spirits of a single root, one mercury and one sulphur are made:

From four are made two, from two again is made ONE,

Which is called the CENTER of the world.

Latin:

Inde

Tot sensus, tot scripta virûm, variæque figurae.

Omnibus ingenio fateor, medicina Metallic

Infirmisque simul, [punctum] Divinitus ortum.

English translation:

Hence

So many meanings, so many writings of men, and diverse figures.

To all I acknowledge the genius the medicine of metals

And likewise the weakness [a point] divinely arisen.

To His Highness the Duke of Orléans, Regent of France

Your Royal Highness made, in your youth, a delightful pastime of what is most rare and most curious in chemistry. In doing so, Your Highness did not believe you were diminishing either the majesty or the Royal Blood that you draw from the august house of which you are today the most brilliant ornament, following the example of so many princes.

It is no longer by the light of furnaces that Your Royal Highness is seen; it is near the throne, of which you are now the most formidable support. There you command, resolve, and cause to be executed whatever is most advantageous to our young Monarch. The ardor of your zeal for the glory of the French impels you to deeds far greater than those that occupied your youth.

The elevation of a powerful mind, that great science of penetrating and overturning the designs of your enemies, that intrepidity, that firmness in restoring public peace and tranquility this wisdom, this moderation in the midst of such vibrant prosperity have been carried to the most heroic heights.

Navigation, so neglected at the close of the previous reign, now begins to strike fear into our neighbors. Injustice and violence are punished and repressed even among the wealthiest subjects. The purity of Religion gains new strength. That most admirable attentiveness to the needs of the people has led you to suppress those odious (and notorious) extortions.

May kings unite in your favor, may they venerate an authority whose power you so ably wield. These are for us magnificent objects of admiration and great titles of immortality for your august name. But from the summit of this glory, deign still to cast your gaze upon a science that you have not judged contemptible or unworthy of your attention.

Deign to honor with your protection a small work that leans upon the authority of Mynsicht, one of the greatest chemists that Germany has produced, and who was the admiration of the finest minds of his century and kindly believe me, with the deepest respect,

Monseigneur,

Your Royal Highness’s most humble and obedient servant.

1. Preface.

It is needless, after so many philosophers have written in all centuries and in so many different languages on the truth of the Science of the Perfect Magistery and will yet write even more in our time to attempt to prove it again, since a learned Anonymous author has placed a very ample preface at the head of his Chemical Library, which was printed in Paris in 1648. The strength, solidity, abundance of his proofs, and his ease in refuting the objections of our adversaries are equally judicious and invincible. Therefore, as I would only repeat what your physician has placed at the head of that Library, I refer the readers to it, that they may be persuaded as I myself have been.

The principal motive of the philosophers for concealing their science has been the fear of confounding social ranks, of rendering the arts useless, and of stirring men to ambition. Yet one must admit they were much mistaken in fearing that this science might become so widespread, since several philosophers themselves were compelled to abandon it, even though they knew all the preparations of the Stone. Thus, if the philosophers themselves forsake it due to the inevitable difficulties it entails, it is therefore absurd to fear that this science will become so common, seeing that it lies beyond the reach of an infinite number of people, and that very few are capable of attaining knowledge of so noble an art.

The laborious toil of the first operation, the length of the second, the diversity of the regimens, the variety of colours which must be precisely observed, and the need for continual application renouncing all sorts of affairs, conversation, walks, and diversions, in a word, dying to civil life so as to devote oneself only to that which concerns this single matter all this, I say, deters many people; and after all that, one often still does not reach the much-desired end.

Thus, how many people are gravely mistaken who, without a certain knowledge of the principles of the Stone much less of its preparation and being unable on their own to distinguish what suits each work left to us by the philosophers to achieve the transmutation of metals, confuse all the proportions and operations, claiming to unite incompatible things. For each work has its own proper matter and its particular preparation. That is why there are so many puffers and so few philosophers that is, so few who truly possess the science of the Magistery.

All the philosophers have left us in their writings, properly speaking, only three proportions (or propositions), or different works, by which to attain the transmutation of metals. The one I present after Mynsicht must be considered the Great Work, either because it is the most natural, the simplest, and the most conformable to the operations of Nature. I could later present the other two works of the philosophers: namely, that which is made from flowing Mercury and its proper Agent drawn from imperfect metals, and the third which is extracted from the gold mine of Hungary and from vulgar gold.

But whether one works upon the first, the second, or the third, one shall learn through experience that the first work though toilsome and laborious is yet less so than the other two. For when it is a matter of fixing flowing Mercury, that fugitive slave of the chemists, it is a true opera; likewise, when it is a question of composing the proper Mercury for the Lesser Work, it entails incredible expenses and difficulties.

This is what moved me to offer to the curious of this science a new Light, or a methodical Work, which by clarifying all the operations necessary to accomplish the Great Work may serve to draw the children of science out of their errors. This Work shall also bestow a new brilliance and an entirely new Lustre upon an Art now so despised, by establishing sound principles and operations that are clear and incontestable.

But if I have clarified matters to such a degree that there is no longer any reason to doubt the root proper to the Great Work, nor its preparation if I have unveiled the whole mystery without envy one might object that I have incurred the anathema so often thundered forth by the philosophers against those who would reveal the secret. I reply in advance, with the Great Hermes, that if the philosophers have shown envy, it was never their intent to hide anything from the virtuous and the wise, but only from the wicked and the depraved. Likewise, I desire to be of service to the wise and the good; and I wish that the wicked may understand nothing of what I shall write concerning the Stone.

I offer to all the preparation of a universal medicine. If the vicious abuse it to their own ruin, then upon them must fall the philosophers' anathema for they will have made of so excellent a remedy a poison. For, as Saint Augustine rightly said: nihil ad bonum quod abutenti non cedat in daemonium, nil tam sacrum, quod suum non habeat sacrilegium “Nothing is so good that, when abused, it does not become diabolical; nothing so sacred that it does not have its own sacrilege.”

If the philosophers' maxim holds, then one must also forbid the use of the sacraments, because the wicked abuse them; one must likewise abandon the cultivation of vineyards (as Mahomet ordained in his Koran) because of the excesses that arise from wine. And so with the rest.

I am still far from wishing to follow the example of the ancient philosophers by employing riddles, allegories, and figures to obscure this Science, which of itself already demands a profound knowledge of the secrets of Nature, a great understanding of the principles of minerals and metals, and a labor worthy of Hercules in order to speak their Language. One must therefore be of good faith and sincerely acknowledge all the difficulties one must encounter along this long and arduous path. For even after acquiring all the light one may hope for in this Science, the first operation is always extremely difficult and laborious. The degrees of heat that must be observed precisely in the second, the number of days for each regimen, the colors that must succeed one another until the color of the wild poppy appears all of this, I say, demands continual application, not to mention the other precautions that must be taken during the imbibition of the Stone and in its multiplication.

Thus, it is truly a marvel if one succeeds in bringing it to completion. This is why the artist must never presume anything until the Work is entirely accomplished, and he must await from God alone the fulfillment of his desires and the end of his labors.

This is what led some philosophers to say that, without divine inspiration punctum Divinitus ortum or a good friend, one can discover nothing of the Work through all the writings of the Alchemists, so great was their effort to conceal it. Even the most sincere among them have spoken so ingeniously of the difficulty of accomplishing the Magistery, for a multitude of others have distorted the matter, presenting its preparation as a child’s game, a woman’s pastime (sum Ludus opus pueriliaque femineum: “I am a childish and feminine game”).

Indeed, in so many places in their writings one reads that all there is to do is to whiten the black and redden the white; and that, once the Stone is completed, nothing remains but to present it to the public thus mocking the credulity of the simple and driving the curious of this science into inevitable abysses and utter ruin.

I suppose that those who wish to work upon the Great Work according to the principles of this new Light will have read and studied thoroughly the writings of the greatest philosophers who have written in depth on the generation of minerals and metals or, at the very least, that they will have acquired a sound knowledge of natural philosophy. But it is absolutely necessary to have studied the best pharmacopoeias, among them the second volume of Ettmüller, which is an excellent work and a compendium of the best that has been written on the subject. That of Charas is also very good. The chemistry of Le Fevre, as well as the chemistry of Lemery which is the most recent and most refined will be of great assistance.

By reading these works, the children of science will learn how to construct furnaces of all sizes, capable of withstanding the most intense heat. They will learn to prepare the proper materials to make a good lute, one that may protect their vessels from the violence of fire. They will understand how to extract salts, what is meant by the vapor bath and the sand bath, and they will not be ignorant of the methods for rectifying spirits and oils. For unless one is well-versed in all these kinds of operations, it would be entirely useless to undertake the Great Work.

I wish to do justice to the one who was my master in this science and to faithfully transmit his writings, which have become very rare. It is enough for those skilled in this art to read them to acknowledge that Mynsicht, a native of Germany, was a chemist of the first rank and an excellent physician. In his Testament on the Golden Philosophers’ Stone, he enclosed all that the most renowned alchemists have written concerning the accomplishment of the Great Work; and his Testament yields nothing in value to that of Raymond Lull.

But this work alone would not have sufficed to draw us out of our errors, had this charitable physician not revealed the matter of the Stone and its preparation in one of his secrets, under the name of the Mineral Unicorn, wherein the entire mystery of the philosophers is unveiled. This double Mercury hitherto impenetrable and so disfigured by the allegories and emblems of the ancients this Agent drawn from Mars, which contains within itself the Solar Sulphur, this kiss of Venus and Mars, made captive under the power of Vulcan within the Philosophical Egg:

Mulciber, capti Marsque Venusque dolis

(Mulciber, and Mars and Venus, captured by cunning).

Here, in a few words, is what the philosophers have always hidden with such artifice: this Mercurial Water, source and principle of metallic nature; this alliance of the things Above with those Below; the four elements reduced to two and then reunited into the sole Mercury of the philosophers. This is the exceedingly secret Work, which is purely natural, and it is this work, says Philalethes, that is accomplished in our Mercury with our Sun not the vulgar one. To this Work must be attributed all the traces and lines that the philosophers have left in their writings as paths to Transmutation.

Mynsicht, in his Testament, speaks as a philosopher who has ignored nothing of the root and preparation of the perfect Magistery. If he used allegories and figures, it was only to avoid revealing the Mystery to all. But in his Unicornu Minerale, he forgets that he is a philosopher and speaks as a most disinterested physician, caring only for the extreme need of the sick and the afflicted, by providing them with this Universal Medicine for which mankind has sighed over so many centuries. Having given the preparation of it, he invites us to go further and to labor at the transmutation of metals, having paved the way for us in his writings.

At the end of this little treatise, I present the Testament of Mynsicht, faithfully copied from a very accurate printed edition, which I leave in the language in which the author wrote it, which is Latin. The curious will prefer to study such an excellent work at its Source rather than read it in a translation that might not do justice to the beauty and elegance of its Latin poetry. I also provide his Unicornu Minerale in the same tongue, which shall serve as a clarification of his Testament. I will translate it as I offer more detailed explanations than the philosopher himself gave for we must admit that Mynsicht wrote only for those already skilled in chemistry, as he himself states.

He also withheld the weight or proportion of the materials in the Philosophical Egg, assuming that one should know it: Philosophum juxta pondus (“The philosopher [acts] according to weight”). He further confused the regimens by placing those of Mars and Venus before that of the Moon. In the end, he said nothing of the number of days required for each regimen. I have supplied Mynsicht’s silence who, without doubt, did not omit these things out of ignorance and I offer a very sure and well-circumstantiated method to reach the end of so noble a path.

The entire expense of the Stone will not be very considerable. The first principles of the Great Work are of little cost, just like their origin:

“Asperam quamvis, æterno vilis” (“Though rough, it is vile for eternity”).

“Testa origo” (“Crude earth is the origin”).

The glass vessels, the furnace, the charcoal, and a few utensils will not cost much. If there is any expense, it is for the fermentation of the Stone with vulgar gold, for there can be no true tincture without gold, says Mynsicht (in a citation possibly found in his work on fermentation), along with all the other philosophers who unanimously affirm:

“In auro semina sunt auri” – In gold are the seeds of gold.

But three or four ounces of fine gold, prepared as we shall describe, will constitute the greatest expense for the Stone. Those who pretend to make a great quantity of projection powder all at once understand nothing: it is not quantity but quality that must be sought in this powder namely, its multiplication, which tends almost to infinity through the repetition of operations.

Finally, one must read attentively the seventh chapter of the Summa of Geber in his first Book, in order to understand what qualities and dispositions are required of the artist. This philosopher demands, among other things, that he possess a great knowledge of natural principles, that he have ardor and continual dedication to the operations of the Great Work, and that he remain constant in his undertaking without changing his principles.

For, says the philosopher, our art does not consist in a multitude or diversity of materials. He must be patient, incapable of anger, for he would break everything. Above all, says Geber, he must always keep in mind that our art is in the hand of God, who grants and withholds His favors as He pleases:

“Verumtamen ars nostra in providentia Dei retinetur, quam cuj vult Largitur et Subtrahit”

Nevertheless, our art is preserved within the providence of God, who bestows and withdraws it at His will.

General Table

Of the Subjects Contained in This Little Treatise

Chap. 1: On the principles of fermentation, or the action of the universal spirit upon all beings, according to Paracelsus and the philosophers

Chap. 2: On the means and the various modes of fermentation

Chap. 3: On the Mineral Kingdom

Chap. 4: On Metallic Principles

Chap. 5: On the Philosophers’ Mercury

Chap. 6: On the agent of fire hidden within Mercury

Chap. 7: In what manner philosophical art imitates the operations of Nature upon the earth

Chap. 8: What the philosophers meant by the Conversion of the Elements

Chap. 9: Explanation of various highly obscure philosophical terms

Chap. 10: That the Root of the Stone must be taken from imperfect metals, according to the philosophers

Chap. 11: The Unicornu Minerale or the Preparation of the Stone according to Mynsicht

Chap. 12: A more detailed explanation of Mynsicht’s Unicornu

Chap. 13: On the laborious Work of the First Operation

Chap. 14: On the Second Operation or the Union of the Materials

Chap. 15: On the Athanor

Chap. 16: Different ways of making the Philosophical Fire

Chap. 17: On the First Regimen, which is that of Mercury

Chap. 18: On the Second Regimen, that of Saturn

Chap. 19: On the Third Regimen, that of Jupiter

Chap. 20: On the Fourth Regimen, that of the Moon

Chap. 21: On the Fifth Regimen, that of Venus

Chap. 22: On the Sixth Regimen, that of Mars

Chap. 23: On the Seventh Regimen, that of the Sun

Chap. 24: On the Imbibition or Refreshing of the Stone

Chap. 25: On the Fermentation of the Stone with common Gold

Chap. 26: How the Projection should be performed upon imperfect metals

Chap. 27: On how to use the Universal Medicine to cure all sorts of illnesses and preserve health

Bonus 1: Testamentum Hadrianeum Mynsicht On the Philosophers’ Golden Stone

Bonus 2: Unicornu Minerale from the same author

Chap. 28: A Summary of the Entire Magistery with the Account of Several Well-Proven Experiments

Chapter 1: On the Principles of Fermentation or the Action of the Universal Spirit upon all Beings, According to Paracelsus and the Philosophers

It is a constant truth that no fermentation can take place unless the air cooperates. For the first dissolvent of the world resides in the air, which undoubtedly contains an invisible, insensible universal spirit, capable of corporealizing and specifying itself in all forms, in all species, and in all individuals of the sublunary world. This spirit is capable, by itself, without any external art, of dissolving minerals, plants, and animals, of uniting with them and specifying itself through them, becoming one with their bodies, all while remaining in its simplicity neither mineral, animal, nor vegetable.

This proposition is universally accepted in all practical philosophy, well-established by Paracelsus, well-described by Mynsicht, and founded on sensible experiments, for there exists in the air an universal spirit that, when it incorporates with beings, dissolves them and reduces them to their primal matter by the passage of time. It is this corrupting and separating spirit, which animates and fills the air, that penetrates the deepest caverns of the earth to contribute to the generation of minerals and metals. This fermenting spirit operates incessantly; but when the seminal and vital spirits of beings are alive, more active, and stronger than it, it unites with them, and they are as if animated, supported, and vivified. Conversely, when the spirits of beings are depressed or destroyed by death, this very same spirit, always active, works upon them to imprint upon them just as leaven does to dough a natural ferment of resolution, through which the bodies are decorporealized, each in its own manner.

Thus it is that the fields are fertile when they are cultivated so that they become permeable to the air, allowing this spirit to penetrate them more deeply and to found in nitre and vegetable juice that which was not present before. All this aligns with what Paracelsus says when he considers the earth as dead in itself and believes that it lives only through the ministry of a universal element with which it is penetrated. It is this spirit, says the philosopher, that has vivified it; it is he who renders it fertile though it be sterile; it is he who causes it to pass through different natures namely those of minerals, vegetables, and animals.

For the same reason it is said that rain fattens the earth: penetrating it more deeply, it brings with it that corrupting ferment which it has received from the air and with which it has been impregnated. Thus the rain enters into composition with the earth to form salt by the sole action of this invisible spirit, which through the same operation thickens the water and subtilizes the earth, in order to compose from both a single salt, which is the proximate matter of vegetables and their nourishment.

This resolution of the earth is a putrefaction of its being it is its manure. And the same vital and natural action of the grain of wheat in the earth is, likewise, a shortcut to the fermentation of the Philosopher’s Stone. Their mercury is a water (est spiritus invisibilis dicta aqua cunctis the invisible spirit calls the water universal), says Mynsicht. Their sulfur is their earth (est spiritus testa factorem it is the spirit that makes the shell). The invisible spirit is their salt (nostra substantia solida est our substance is solid), this spirit which subtilizes the earth and thickens the water to make from both but one inseparable compound.

Thus the Stone is triune-one, which we shall prove more fully later on.

Chapter 2: On the Different Modes of Fermentation

It is also a constant truth that all sublunar Nature is subject to the action of the air, and that nothing is accomplished in any operation except through its influences and indeed through the admirable mixture of this universal spirit, which takes on a bodily form in as many ways as there are different magnets that attract it, after having themselves been formed by it.

This is the doctrine of the Cosmopolite, who affirms that air is the principle of the different magnets:

aëri dei philosophes generat magnetem, magnes vero generat vel facit apparere aërem nostrum

"The air of God engenders the magnet of the philosophers; but the magnet in turn engenders or causes to appear our air."

"...to pass over in silence..."

est aqua roris nostri, ex aqua extrahitur salpetra philosophorum quo omnes res crescunt et nutriuntur

"It is the water of our dew; from this water is extracted the saltpeter of the philosophers, by which all things grow and are nourished."

To pass over in silence many other experiments of the philosophers and to shorten their views which all revolve around the various ways in which the universal spirit acts upon sublunar bodies it all returns to this one principle: that this miraculous spirit is the first agent of the world. It enters into action with all beings, whatever their kind; it penetrates them all, opens them, and resolves them; it also unites and incorporates itself at the same time with all, taking on different forms and figures according to the specification it receives from each being with which it is united and co-fermented (which ferments it?).

Are these not the essential conditions that all philosophers, following Paracelsus, require for their radical dissolvent? Chief among them is that it must be homogeneous with what it dissolves, and become so united with it that it can no longer be separated. It is certainly from this universal source that the philosophical dissolvent must be drawn.

What remains is only the subject or the magnet that must be employed to corporealize this spirit. This is easy to demonstrate through all the sublunar kingdoms, there not being one upon which it does not act. There is only this difference: that some must be treated by air alone, as is seen in the case of the Roman vitriol ore, which of itself by the action of the universal dissolvent calcines, pulverizes, dissolves, and turns into vitriol without any addition or help from other means. It is also from this mineral that the philosophers take the root of their universal medicine, in accordance with Mynsicht, as we shall say in its proper place.

To demonstrate this more clearly, it will not be out of place to relate how this Roman Vitriol is obtained from a place called Sylvena, not far from the city of Rome. The inhabitants of that area extract it from caverns, much like a clay or blackish potter’s earth, which has very little taste. To obtain vitriol from it, the locals lay this earth under open sheds, forming furrows about two feet thick and wide. They leave it there, sheltered from the rain under a simple roof but without any walls, so that it remains permeable to the air.

After some time, this earth heats up by itself, like horse manure, and smokes in such a way that, if these furrows are not turned from time to time as grain is stirred in a granary to prevent it from overheating and sprouting the fire would catch in the earth and consume it. Thus, by turning this clay from time to time, it fully breaks down and rots, becoming vitriol.

Is this not the very manure of which the philosophers so often speak, found within beings and in every kind of nature, through the action of that Divine agent unchanging, eternal, tireless which becomes all with all things: animal with animals, mineral with minerals, and finally metal with metals? It is for this reason that the great Hermes declares:

“Quod est superius est sicut quod est inferius, et quod est inferius est sicut quod est superius, ad perpetranda miracula rei unius.”

“That which is above is like that which is below, and that which is below is like that which is above, to accomplish the miracles of one single thing.”

That is to say, of the Philosopher’s Stone, as Hortulanus explicitly states in the Tabula Smaragdina (Emerald Tablet).

Is not this argument sufficiently well established to persuade even the least skilled and least experienced of the perpetual action of the universal spirit, which many philosophers have called their Mercury since it dissolves everything, unites with everything through a permanent and inexhaustible operation, and elevates inferior spirits to a nobler and more perfect dignity by the communication of its superior and universal spirit, which brings about the perfection of all Nature?

One should therefore not be surprised that several philosophers have sought to draw from sea salt the matter of a Universal Medicine, since today even the most skilled philosophers all agree that the origin of the salinity of the sea is nothing other than a sensible corporification of the world’s universal salt with the waters of the sea. This salt is invisibly diffused throughout all of Nature and resides within the vast expanse of the air, where it is engendered and sustained by the light of the stars this being founded upon the unchanging principles of Nature. Moreover, it is also true that philosophers believe this sea salt partakes more of the central salt and is better "cooked" by the heat of the sun's rays than any other salt.

Common nitre (saltpeter) has also had its proponents. It has always been held in high regard in chemistry. Most alchemists, with Glauber, have claimed to derive from it a universal menstruum, and other philosophers believe that the matter of the Philosopher’s Stone resides in nitre, because according to Quercetan nitre is composed of two volatile parts: one sulfurous and the other mercurial-acidic. It contains two salts: one fixed and the other volatile, which is why it is called hermaphroditic because it is both saline and sulfurous.

But though nitre partakes of mercury and sulfur, like minerals and metals, it does not have the same principles nor the same fixity. One of the proofs of the quality of saltpeter is that it must burn completely for if a white salt remains after calcination, it is impure and poorly refined. Thus, nitre cannot withstand all the necessary preparations to be in a condition to transmute metals and to give them a fixity capable of resisting the greatest fire, since it itself is dissipated by the slightest attack of Vulcan.

Nevertheless, nitre is of great use in medicine.

Chapter 3: On the Mineral Kingdom

We are not speaking here of common earth, but of mineral earths, which are not simple soils, but rather mines composed of certain metallic veins, more or less simple depending on the diversity of locations, and always impure and imperfect because they have not yet acquired their maturity and the hardness of metal. Over time, these impure metallic veins change into a coarse substance in subterranean places and are impregnated with the central salt of the earth, or are mercurialized. For the warm, moist vapors, moderately saline, which travel through the center of the earth, when they encounter an unmatured metallic vein, corrode and dissolve it and by thoroughly penetrating it, they transform it into a friable substance.

This is the origin of vitriol, which is nothing other than the dissolution of a copper or iron ore, effected through the ministry of an acid and sulfurous spirit, which, in corroding said ore, coagulates with it and forms the body called vitriol. The ore of Mars (iron) gives it a green color, and that of Venus (copper) a blue one.

All of this is demonstrated by the artificial composition of vitriol: one stratifies Mars or Venus with sulfur in order to calcine them, and through the means of calcination, the sulfur imparts its acid spirit, which corrodes the iron or copper. The calcined matter is then infused in pure water, producing a green solution. This solution is filtered through grey paper, then evaporated down to a pellicle (a thin film). It is then placed in a cane (a crystallization vessel), where crystals form green or blue depending on the metal chosen yielding a beautiful and true vitriol, which possesses a nobler and more excellent virtue and efficacy than that obtained from the mine, according to Le Fevre, the renowned English chemist.

Vitriol is a mineral salt that closely approaches the metallic nature, particularly that of copper and iron.

Chapter 4: Of Metallic Principles

One must suppose, before entering into the subject, that metals in general are generated in the bowels of the earth from a saline substance in liquid form or from a viscous sap, by the agency of fermentation, which serves to change them into solid bodies. This fermentation proceeds from a seminal saline principle of metals, which in this way gives consistency to the subterranean metallic juices. And this universal principle is ordinarily saline-sulphurous; thus, the difference between metals arises from the diversity of the juices the more fermentation matures and purifies them, the more noble the metal becomes. When it is well matured, the metal becomes fixed and resists fire; otherwise, if the metal is not sufficiently fixed, it is destroyed by fire. Consequently, the purer, more mature and more fixed a metal is, the more noble it is; and the less pure, fixed, mature, and perfect it is, the less noble it is. From this depends the gradation of metals, and it appears that gold is the most perfect of all, because it is the most fixed and resists fire the longest. The others are impure and imperfect, since they easily melt in fire.

Imperfect metals are of two kinds: hard and soft. The soft ones are liquefiable and melt immediately in fire without reddening; they are composed of a moist mercury that is too watery and little fixed, and of a sulphur that is fusible and combustible. The imperfect hard metals, on the contrary, are easily reddened in fire without melting; they are composed of much non-liquefiable sulphur and of a mercury that is fixed and fixative, with an acid salt that binds the two principles to one another to speak the language of the chemists.

Imperfect metals have three principles: namely, mercury, sulphur, and salt not that these names refer to the common substances that bear them. For by mercury is understood the radical moisture of the metal, which abounds especially in lead and tin. By sulphur is understood an acidic, greasy substance, where the acid predominates this substance forms the better part of the metals, even of gold. By salt is understood a very fixed substance of the nature of alkalis, which binds the sulphur and works together with the other principles to form the metallic substance.

One must also observe that in all metals there is a great deal of sulphurous acid some noble, some less noble. To begin with the most evident examples: this acid is so abundant in iron (Mars) that, when dissolved by the moisture of the air, it corrodes its own body and turns it into rust, which is called Crocus Martis or Saffron of Mars. Copper contains much of this acid, which, when dissolved by some moisture, turns into Verdigris or Saffron of Venus. There is also much of it in lead (Saturn). Tin likewise contains a great deal of acid. Even gold is not without much of this acid, which is evident if one places an iron rod into molten gold: upon withdrawing it, the rod appears just as corroded and rusted as if it had been dipped in common molten sulphur. Thus, it is known that acid predominates. It is therefore certain that metals abound in acidic sulphur something I ask you to note carefully, because it is one of the greatest secrets of the Art. For the whole point is to separate this acid, or this imperfect sulphur, from the less noble metals before transforming them into noble ones.

Since all metals share the same root, as we have seen, they differ only by degree of perfection; and in this regard, one may consider what is to be thought of the transmutation of metals, and whether it is possible to make gold from another metal by rendering it more mature and more fixed. The affirmative must prevail, says Ettmüller quite rightly, although the means of succeeding in this are difficult and little known. For, as this author says, the whole matter depends on fixing what is volatile, maturing what is raw, and perfecting what is imperfect. If one fixes silver, it becomes white gold; conversely, if one removes from gold its yellow color, it becomes fixed white silver.

Daily experiments further prove that less noble metals contain something of the more noble. Iron contains a certain solar salt and sulphur. The first matter of silver lies within copper. In lead, one always finds some grains of silver when it is calcined. There is always a little gold in silver and in tin thus proving that there is an affinity and correspondence between metals, between the perfect and the imperfect, which are only imperfect because they are imperfectly formed in the earth. Their perfection is hindered, and they remain imperfect unless, through chemical art, one bestows upon them the perfection of the more noble ones.

It should therefore be no surprise that metals are never found alone, but always near one another so that where there are gold mines, there is also tin or some other metals; and there is always copper near silver mines, and often tin mixed with silver. This leads Ettmüller to conclude that the transmutation of metals is possible, though indeed difficult.

Here, says that author, we arrive at the mystery of the Philosopher’s Stone, which serves not only to change metals into gold, but even to transform mercury itself granted (as is true) that metals differ from each other only by degrees of fixity and softness, of maturity and immaturity. It is therefore reasonable to judge that if one possessed a very perfect metallic seed, one could by its virtue perfectly mature those metals that are not yet matured.

This is the Philosopher’s Stone: a remedy to open the metals, to correct their morbid imperfection, and to grant them the perfection of health. In the following chapters, we shall give the method of preparing this most perfect seed, which serves to very perfectly mature the metals. This is what is called the Powder of Projection.

Chapter 5: Concerning the Philosophers’ Mercury

There are three kinds of Mercury: namely, the common (vulgar) Mercury, the Mercury of bodies, and the Philosophers’ Mercury. Common Mercury is what is ordinarily called quicksilver. The Mercury of bodies is that which is drawn from other metals, and is called resurrected and metallic Mercury. The Philosophers’ Mercury, which must be the matter of the philosophical menstruum, as Ettmuller very rightly says, and even the very method of the Philosopher’s Stone, in no way partakes of vulgar Mercury; it is drawn neither from the vegetable kingdom, nor from the animal kingdom, but from the mineral kingdom, and from the metallic principle, or the primal matter of metals not from perfected metals.

Nothing conforms more to what Mynsicht has left us in his writings concerning the making of the Philosopher’s Stone than what I have just reported from Ettmuller; one need only examine and seriously reflect upon Mynsicht’s Mineral Unicorn to see the agreement of their principles.

Before writing what Mynsicht has prescribed for surely attaining the transmutation of metals, it is necessary to recount the opinions of several philosophers in order to support the views of Mynsicht and Ettmuller. It is said in The Crowd (La Tourbe / Turba Philosophorum), or the assembly of Pythagoras’ disciples which is a very ancient and excellent work wherein a philosopher, speaking in his turn, says: “Our composition is made of two things: Mercury and Sulphur,” which are made one in the philosophical egg, and it is then called white bronze; and when all is overcome, it becomes quicksilver (not the vulgar), and is a perfect tincture. All consists in dissolving, in reducing everything to its first principles, in vivifying and spiritualizing the matter. But be assured, adds this philosopher, that nothing tinges metal but metal itself in its own nature, and that no nature is amended except in its own nature.

Pythagoras himself says, in the same book: “Living water” (he means Mercury) “has a certain body to which it is joined.” Leave aside human nature, leave aside volatiles, sea stones, and brute beasts; but take metallic matter. This is why the Count of Trevisan assures us that what most helped to free him from his errors, which had lasted more than forty years, was this writing attributed to Pythagoras and especially this passage: “That nothing tinges metal but metal itself in its nature, and that no nature is amended except in its own nature.” He often repeats this passage in his writings to convince and persuade us that the Philosophers’ Mercury must be taken from metals, or from metallic principles, or from the primal matter of metals.

One must not believe that it is in vain that the philosophers all command us, and prescribe to us in their writings, to use the same method to perfect metals on earth as nature uses in the mines to create them. Thus, our entire science consists in imitating nature in its operations as much as is possible for us, by making use of the same principles similar to those used by nature in the mines.

But as we have said, according to the chemists, the imperfect metals have three principles: namely, Mercury, Sulphur, and Salt not the common substances that bear these names. Therefore, we shall make use, as Mynsicht instructs us, of a viscous water which everyone desires (aqua diluta lunetia = water diluted), and our Sulphur is a deep red in the form of oil (sulphur sub forma olej rubicundum anfom̅ = Sulphur in the form of a reddish oil). This author adds that in our Salt are enclosed all the secrets of our science (in sale cuncta latent arcana = all secrets lie hidden in the salt).

These three substances are of the same origin, from a mercurial source, and when united, they together compose the Mercury of the Philosophers. For according to the alchemists, the Philosopher’s Stone must be made from one single and simple Mercury, which they candidly call a mercurial water coagulated by the action of its own Sulphur this having acquired, through long and continual boiling, such a great perfection that it can perfect the imperfect metals when united with them by projection.

There, in a few words, is the Mercury of the philosophers well explained. This is how those who possessed the science of the perfect magistery have happily reached the end of the Art, by imitating nature as much as possible.

But if it is not within our power to create metals, our science knows how to reduce them to their first principles. It also knows how to sweeten them, after having removed all their malignity, and after having made them pass through a thousand different forms, art knows how to give them body. For although the metals are so compact and united that it is difficult to divide them, and although most vulgar operations do not completely separate the parts of metals but only prepare and exalt them so that our natural heat can subdue them it is undoubtedly a failure of good faith, and a ridiculous stubbornness (says Schröder), to maintain the impossibility of such separation against an infinity of daily experiments.

Chapter 6: On the Agent of Fire Hidden in Mercury.

Nature, in the creation of metals, after having formed the matter namely Mercury joined to it its own agent, which is nothing other than a mineral earth, like a kind of cream or grease of that earth, cooked and thickened by its own heat, which takes a long time to warm within the mines through the natural movement of the celestial bodies. This agent also acts upon the cold and moisture of Mercury, and according to the various degrees of alteration, causes it to pass into various metallic forms.

The Philosophers have called these agents sulfur, or hidden fire within the Mercury, because it is a combustible substance like sulfur, hot and dry like sulfur not that they mean common sulfur, but only by comparison. This is what led Geber to say that in the depths of Mercury there is a fixed sulfur, which is of Mercurial nature and of no other substance.

The Philosophers (Marlenus and Aros) confirm this view when they affirm that Nature, in the mines, has no other matter with which to work than pure Mercurial form. They also say that within Mercury there is an incombustible sulfur that perfects the Great Work, and that no other substance is needed beyond pure Mercurial essence.

Chapter 7: How the Philosophical Art Imitates the Operations of Nature in the Earth

Nature, desiring to reveal the force and power of the agent within Mercury, has by an admirable composition caused the metals to be congealed by the action of fusible sulfur, so that they may be meltable. She has likewise formed the other metals through the action of non-fusible sulfur, so that they would not be meltable. But because the agent cannot be the Mercurial part of the compound (as Aristotle says), Nature, working beneath the earth in the creation of metals, after having mixed Sulfur with Mercury in an indivisible union, composes and perfects gold, the noblest of metals.

For the sole aim of Nature is always to tend toward their perfection, unless she is hindered by some obstacle she cannot overcome. Thus, just as gold is nothing but Mercury perfected in its own Sulfur and completely separated from it by a perfect cooking, so also the separation of Sulfur is the cause of the perfection of gold. In the same way, because much of it remains in the other metals, they are imperfect.

This is the reason why silver is less perfect than gold, copper less perfect than silver, and so on with the rest. It is also by cooking that the Sulfur must be separated; but one must observe that Nature uses a very different method in the creation of imperfect metals, which is nothing other than to purge and cleanse them of their imperfect Sulfur through a long and continual digestion, until they reach the degree of perfection required for each metal.

It is in this manner, which Nature uses to perfect imperfect metals, that our science imitates her in its operations by perfecting the imperfect metals through the removal of their Sulfur, which is in fact separated by means of the Powder of Projection, which we compose through chemical art, and which has the power to change them into gold or silver, by the perfect and overflowing heat which we have provided it through our science.

This, says the Philosopher Zacharias, is again the greatest secret of our art revealed. For just as art must imitate nature in her operations, it must also separate the Sulfur before accomplishing the Great Work, so that our Stone may become a true medicine and a most perfect metallic seed, to correct the morbid imperfection of imperfect metals and give them the perfection of health.

This is what all the Philosophers have carefully concealed in their writings, by referring us back to the operations of Nature.

This is why the substance which the Philosophers have called animated Mercury or living silver that is, Mercury joined with its own Sulfur shall be the true matter of our science for accomplishing the Great Work, since it alone, without any other means, is used by Nature in the mines for the generation of metals.

The reason this matter is called animated Mercury is to distinguish it from flowing, or common Mercury, which remains such because Nature has not joined to it its own Sulfur or agent.

Let us then conclude with Geber, who says in his Summa that our living silver or Philosophers’ Mercury is nothing other than a viscous water thickened by the action of its own metallic Sulfur. This is our true matter for composing the Philosopher’s Stone, which Nature has prepared for our science, and which is known only to the true chemical philosophers.

Chapter 8: What the Philosophers Meant by the Conversion of the Elements

It is necessary to clearly explain what the Philosophers intended to convey by the conversion of the Elements. For once this conversion is well understood, it provides a certain knowledge of the true matter and a secure practice of the whole Art.

The Philosophers meant to teach that the four Elements, being confused together in the prima materia which Holy Scripture calls chaos have been revealed to us through their outward actions. Therefore, they called fire everything that possessed a hot quality; all that was dry and condensed, they called earth; all that was moist and fluid, they called water; and all that was cold and airy, they named air.

All mixed bodies are composed of these four Elements, although often they are hidden within one another. As in the Philosopher’s Stone, there are only two Elements that appear outwardly namely, water and earth. The air is hidden within the water, or Mercury, and the fire within the earth, or the Sulfur of the Philosophers. Yet these two Elements (air and fire) cannot manifest their action except with the aid of the other two.

This is why the Philosophers affirmed that the compound is perfect when moisture and dryness are equally united by the help of Nature, together with cold and heat which is brought about by the conversion of one into the other.

This, they assure, is necessary in order to attain a perfect understanding of the Great Work. For in the beginning, there appears only a Mercurial Water; and from this water is formed the earth, or the sulfur, when it is thickened through cooking and union without which it is useless for the perfection of the Stone or Mercury.

This is what led the great Hermes Trismegistus, that incomparable Chemist, to say that from our earth the other Elements proceed, because at the end of the second operation, it alone manifests its qualities, just as the water had shown them at the beginning.

Let us hold to these two Elements, which the Philosophers have commanded us to know very perfectly before working upon the Philosopher’s Stone. In a word, this conversion of the Elements, as Raymond Lull rightly says, is nothing other than causing the earth (or sulfur), which is fixed, to become volatile, and the water (or Mercury), which is volatile, to become fixed through a continual cooking in the Philosophical Egg, never opened until the Stone has reached its final perfection.

Chapter 9: Explanation of Various Obscure Terms Used by the Philosophers

First, to understand the term Leaven, which is a mysterious expression of the Art, it must be taken in two different senses.

The first is by comparison with other metals: just as a little leaven changes a great mass of dough into its own nature, so too this leaven (or this Philosophical Sulfur), being most pure gold when perfected through our Science, likewise possesses the power to change imperfect metals into very pure gold at a hundredfold its weight.

In the second sense, the term Leaven should be understood as the true matter that accomplishes the Great Work. This method of perfecting the Stone, say the Philosophers, is not perceptible to the senses but must be grasped by the understanding. For at the beginning of the second operation, the Mercury appears volatile within the Philosophical Egg, which must be joined with its own body (or sulfur), in order to retain the soul which is accomplished, say the Philosophers, by means of the spirit.

This is why it is said in The Turba that the body is stronger than its two brothers, by which they mean the spirit and the soul. To clarify these expressions well, one must understand that these Philosophers, following Aristotle, call body any compound that can endure the fire without any diminution; by the word soul, they mean any compound that is by nature volatile and has the power to carry off the body with itself from the fire; and by spirit, they mean something that has the power to reunite the body and the soul, and to bind them so closely together that they can no longer be separated, whether perfect or imperfect.

Though nothing enters the Philosophical Egg after the matter has been sealed within it, the Philosophers have called one and the same thing body, soul, and spirit for different reasons.

There have been philosophers who compared their Matter to a salad or rather, to what must season it. For just as a salad needs vinegar, oil, and salt, so too have the Philosophers called their Mercury a very sharp vinegar, because it dissolves all metals. They have likewise called their Sulfur an igneous oil, and the spirit that binds the Sulfur and the Mercury they have named Salt.

To further clarify all this, one must understand that the Philosophers spoke in their writings only of the matter fully prepared and when it is within the Philosophical Egg. They always took great care to conceal the root or composition of the Stone. They speak of the second operation through metaphors and allegories, so that everything is full of obscurities regarding the colors, the regimens, the quality of fire, and the timing of each stage. All of this is meant to explain the various motions or circulations of the matter inside the Philosophical Egg, which occur through the action of the external heat, aiding the internal heat to overcome that which resists it.

Thus, when the matter rises to the top of the vessel and dominates during several regimens, the Philosophers call it soul, volatile, female, and Mercury. But when the matter thickens and remains at the bottom of the vessel, they call it earth, body, fixed sulfur, and male which has the power to change the Mercury into its own nature, after having fixed it by means of the spirit, which is their salt.

The Philosophers have also called their agent, or Sulfur, a venom and poison, because it kills and fixes the Mercury. They call it male because it gives action, and to the female or Mercury they attribute passion. They also give wings to the female because she is volatile and is restrained by her coagulated counterpart that is, the Sulfur to which they ascribe none.

We would go on too long if we attempted to explain all the metaphors and allegories of the Alchemists, which have served only to confuse practitioners and to drive them into error and extreme expense.

Finally, let us conclude this chapter by affirming with truth that we add nothing foreign to our matter. For, as Count of Trevisan rightly proves, within the Philosophers’ Mercury is enclosed the fixed and incombustible Mercurial Sulfur, which does not, however, dominate at the beginning of the second operation, but rather the moisture and coldness of the Mercury until, through the action of persevering heat, the fixed dominates the volatile and overcomes the coldness of the Mercury. And according to the various degrees of this alteration of the Mercury by the action of the Sulfur, different metallic colors are formed, all similar to those seen in the operations of Nature within the mineral earths.

The first is the Saturnine blackness, the second the Jovial whiteness, the third the Lunar, the fourth the Venereal, the fifth the Martial, the sixth the Solar, and the seventh, says the Philosopher, is one we push by our art a degree beyond what Nature can achieve since our Stone, when perfected, is of a color purplish or like wild poppy. For if it were not more perfect than common gold, of what use would be so much labor and a regimen of nearly ten months, if our gold were not more than perfect, so as to be capable of perfecting the imperfect metals through its abundant irradiation in weight, in color, and in mineral principles so that it may transform the imperfect into its own perfect qualities.

Chapter 10: The Root of the Stone Must Be Taken from Imperfect Metals According to the Philosophers

We have already mentioned in the work (Turba Philosophorum) attributed to Pythagoras, or one of his disciples, that we are assured that nothing fixes a metal except the metal itself in its nature, and that no nature is amended except in its own nature. Therefore, it must be concluded that the root of the Stone must be taken from the metallic nature, according to this work, which is confirmed by Philalethes when he says that there is something in the metallic realm of a marvelous origin, in which our Sun is closer than in the common Sun and Moon. If you seek it at the time of its birth, it resolves and melts into our Mercury, as ice melts in hot water, and it is in some ways similar to common gold.

This is the work or the medicine of the second order, which is done with common Mercury and a metallic Sulfur (which he does not name) that fixes this Mercury. Philalethes then adds: "You will not find this in the common Sun, but from it through our Mercury, by digesting and cooking for the space of one hundred and fifty days; you will find there our true matter, which is gold."

This is the medicine of the first order, as Geber calls it, or the small work, which is done with the Hungarian gold mine and common gold. I know, this philosopher adds, "both of these two ways, I approve the first one as the easiest and shortest." It is clear from this author that the gold or the Sun of the philosophers is found in a marvelous way in the metallic realm rather than in the common Sun and Moon; that is to say, from gold or silver.

This philosopher then adds that he has read in authors who have left in their writings three proportions or different works to make the Philosopher's Stone. He proceeds to mention two of them: the first, which he approves as the best and shortest; the second, which he explains at length in his book, though it is the more difficult and costly. But this same philosopher candidly admits that there is also a third proportion or the medicine of the third order, or the great work. He confesses that this way is very secret, purely natural, and is done with our Mercury and our Sun, not the common ones. This is the work, says this author, to which all the signs left by alchemists in their writings to mark the great work must be attributed. This work is only accomplished through the interior heat alone, for the exterior heat only serves to chase away the cold and to correct and overcome accidents. This proportion that this philosopher has not clarified or explained in his book, although very secret, very simple, and natural, is the one Mynsicht left us and explained in his writings, which is derived from Venus and Mars, as we will explain in the next chapter.

Finally, Philalethes in the third chapter of his book had already said that the steel of the sages was the true key to our work, without which the lamp's fire could not be lit; that it was the gold mine, the extremely volatile hidden end in its kind, the composition of celestial things within the terrestrial. Therefore, it is not without reason that the philosophers speak so often of the "leton of Venus," the "red man of Mars," and the "red Sulfur" in their writings; since it is indeed from these metals or their first principles that the Philosopher’s Stone must be composed according to Mynsicht.

Let us conclude this chapter by saying that our Mercury, although composed of several principles, does not prevent it from being a single and unique thing, made of various substances incorporated and united together, all of which share the same essence. As Aristotle rightly said, when the agent and the matter are alike, the operations are always alike, even if the means to carry them out are different. For the means and the matter are two different things; but if the matter is one, and entirely alike, all the operations which may seem to be contradictory at first, will ultimately produce the same effect.

Moreover, it must be that in our Mercurial water, there is the incombustible Sulfur, and the spirit or Salt that binds Mercury and Sulfur. But in our composition, the Sulfur holds the middle ground between the mine and the metal, which is neither one nor the other, although it partakes of both. It is the fiery dragon of which the philosophers make so much noise in their writings, which overcomes all, although it is permeated with the odor of our Mercury. From both, a marvelous body is formed, which is not, however, a body, because it is volatile at the beginning of the second operation; it is spirit and yet not spirit, because it resembles molten metal in the fire. Thus, it is indeed a chaos, from which so many wonders must emerge; and it is to the imperfect metals what their mother is to them.

All of this has been clarified by the writings of Mynsicht and will indubitably prove that his principles are fully aligned with those of the most famous philosophers.

Chapter 11: The Mineral Unicorn or the Preparation of the Philosopher’s Stone According to Mynsicht.

We have finally arrived at the Philosopher’s Stone, or rather at what should compose it according to Mynsicht. In his preface to his Unicornu Minerale, the philosopher candidly admits that this science should have remained hidden until now due to the misuse that wicked and unworthy people could have made of it. However, driven by a truly Christian affection and by a secret movement of divine inspiration, he would have liked to reveal the mystery and make it public, combining it with so many other chemical preparations that he had acquired knowledge of, either through his own work, through celestial light, or through the favor and goodwill of the most skilled spagyricists who had kindly granted him such a great secret, so that he might communicate it to the children of wisdom without any personal interest, making no difficulty in believing that they received this great gift, which was the universal medicine, with great joy, much satisfaction, and a singular piety toward God.

Take natural green vitriol, known only to the philosophers. If unavailable, take crystals of Venus’s vitriol, well purified by sublimation, so that no earthly matter remains. Place them in a good retort, tightly sealed, and heat gradually and strongly until you obtain an oil that turns red. Keep this oil very carefully for future use.

Then, take the dead head (caput mortum) that remains at the bottom of the still, dissolve it in a suitable menstruum, and when you have filtered it, place the liquid in a cane. It will form crystals with the nature and flavor of vitriol. Calcine the dead head (caput mortum) again and repeat the crystallization a second time. This second crystallization will be of no use for this mystery. Continue these operations in the same manner until no more smell of vitriol is discernible. Calcine the dead head (caput mortum) violently, but gradually, to extract a very fine and pleasant-tasting salt, which you will keep carefully for later use. Meanwhile, remember this axiom of the philosophers: "Visit the interior of the Earth, rectifying what you have extracted from it, and you will prepare a hidden stone, which is a true medicine."

Note that the initial letter of each word in this Latin axiom forms the word "Vitriolum." Then, take your vitriol oil as described above, and sprinkle it onto steel filings, adding a sufficient quantity of hot water to prepare Mars's vitriol. Dissolve this vitriol in distilled rainwater to form crystals. Repeat this work until you have separated the pure from the impure, so that, when the fermentations are complete, you will have very clear and shining crystals. Distill these Mars crystals as you did those of Venus, with a violent fire, until you have drawn out an oil of dark red.

You must take great care to rectify it well. At this point, you will have the mineral blood of the Red Lion and the Sulfur of Mars and Venus in its full strength, which Vulcan has reduced under his irons, according to this axiom: "Mulciberi capti Marsque Venusque, dolis" (Mars and Venus, captured by the tricks of Mulciber).

Extract further from the dead head (caput mortum), or from what remains at the bottom of the still, a salt that no longer has any taste of Mars. Do this in the same way as you did with the salt of Venus’s vitriol. Mix these two salts in equal weights, place them in a glass vessel, and place the vessel in a cold place to allow them to dissolve into a Mercurial water. Then take this water, from which new crystals will form, and at this point, you will possess the double Mercury of the Philosophers namely, the Salt of Wisdom and the Salt of Nature, the salt said to be of the Philosophers, under which the center of the world remains hidden.

This double Mercury, which has always been carefully hidden from human knowledge, is something that no philosopher before me has written so clearly about, although in somewhat obscure terms, yet sufficiently intelligible for even the least experienced chemist to understand. You must proceed further, having elevated your mind with more sublime thoughts. This Mercury, which the Philosophers have called Rebis (that is, a thing twice), you will use for the purpose I will now outline; as an earthly treasure, a very excellent gift from God, and a very rare secret.

Take the above Mercury, and the Sulfur of a very dark red, and by joining these two things, in the exact weight specified by the Philosophers, with all the spirit of a sublime intelligence. However, be careful that the chemical vessel you use has three-quarters of empty space, and that only one-quarter is filled. The vessel must be sealed hermetically, and the material must be heated by gradual Philosophical degrees, maintaining a continuous heat, until it coagulates into a mass, which you can then further perfect by new melting processes as much as you wish, making it more valuable in a short time through fermentation. By this means, you will have completed a Great Mystery.

Furthermore, you will notice before the coagulation of the stone several admirable figures and colors, which you should carefully observe with great attention, to glorify God and to use them to benefit the whole world.

This is the universal medicine and a treasure salt that has the power to cure all kinds of diseases that may afflict creatures; one grain, two, or several of this secret, depending on the quality or temperament of the patient, will penetrate the entire body like a subtle spirit, driving out all corruption and malignancy in a short time. This medicine will perfectly restore the sick and renew them entirely; but it also serves as a preventive to avoid all morbid accidents, if used occasionally, until the appointed time marked by the Most High for the end of each creature.

This precious medicine, having been fermented according to the philosophical art with very pure gold, will have the power to purge all imperfect metals of their natural sulfur, transforming them into very fine and very fixed gold. But for such a great work, and so immense, and for the communication of so many gifts and divine wisdom, praise and glory be to God for ever and ever.

Chapter 12: Further Explanation of the Unicorn of Mynsicht

Mynsicht instructs us in his Unicornu Minerale to use natural green vitriol, which is known only to the Philosophers, because we are provided with it from various states and kingdoms, not all of which are suitable for the Great Work. The one from Cyprus is highly esteemed in itself, but since it is blue and very compact, it is not suitable for composing the stone. The Roman vitriol, which is green and partakes of Venus, will be good for our mystery; the one from Sweden will also be good because it is green and partakes more of Venus than of Mars. One can also use that which is obtained near Spaa (a municipality in Belgium) and sold in Liège. However, those obtained from Germany and England are of no use for the Work because they are more akin to Mars than to Venus. In short, one should always choose natural green vitriol that partakes more of copper than of iron. The best of all is the Roman one; it has qualities that the others do not have. It is used to make the famous sympathy powder.

Mynsicht adds that in the absence of natural green vitriol, one should take the crystals of Venus vitriol, well purified and precisely prepared by sublimation, so that nothing impure remains. This Venus vitriol is prepared as we have already described in Chapter Three, by layering copper sheets or filings with sulfur; through calcination, sulfur releases its acid, which corrodes the copper. The calcined material is dissolved in simple water, and the solution becomes green, which is filtered through gray paper. The moisture is evaporated until only a thin film remains, then it is placed in the cane, where blue crystals form, producing excellent Venus vitriol. There are chemists, including the English Fevre, who teach how to prepare it with the verdet from Montpellier. The spirit and the oil obtained from it are of incomparable virtue, and especially the volatile spirit, which is an excellent remedy for brain diseases such as apoplexy, epilepsy, lethargy, paralysis, and other ailments that affect the principles of generation. It is also a dissolvent that never fails in its operation and loses none of its strength even after several operations. Therefore, there is no disadvantage in using the crystals of Venus vitriol in place of natural green vitriol, as one might doubt the choice of natural green vitriol as Mynsicht demands, but one cannot doubt the choice of the crystals of Venus vitriol.

Mynsicht, after declaring the Matter for the composition of the Great Work, says nothing about the quantity to be taken; however, I believe, after some experiments, that one should take the weight of twenty or twenty-five pounds. The Vitriol must be purified of its dregs before use. It will suffice to dissolve it in common water, filter it, and crystallize it through the required digestion, and then allow it to dry.

It must be admitted that if one were skilled in chemistry, fifteen or sixteen pounds of Vitriol would suffice, as there will always be enough oil, but when it comes to calcining the dead head to extract the Salt, one will never have enough to compose the Mercury of the Philosophers, as I have experienced due to not having taken enough. Therefore, to avoid any risk, one can arrange a price with a skilled chemist to provide a certain quantity of vitriol oil and salt, already prepared for a specific sum of money. But to be certain, one should be present during the operations to ensure everything is done according to Mynsicht, or at the same time to learn how to carry out such operations. One can also agree on the price for the crystals of Venus vitriol. Six or seven pounds of crystals will suffice to obtain the oil and salt of Venus, but they will cost much more than the oil and salt of Roman vitriol.

However, if one wants to work alone, one would proceed as follows. Since it is not essential to have the volatile spirit of Vitriol, the ordinary method should be followed by calcining the Vitriol until it becomes red. The loss of spirits that occurs during its calcination is of little consequence and greatly shortens the work, provided the calcination is not too intense and the fire is properly proportioned in the distillation. The calcination of the Vitriol is simple and is done in a crucible or iron pot over hot coals. The material first turns white, then yellow, and finally red. Afterward, one must quickly place the calcinated material in a good Lorraine glass retort, proportioning it to the material so that the retort is filled no more than halfway. The retort should be well sealed, and it should be placed on a closed reverberatory furnace so that there is about an inch of space between the retort and the furnace. A large container should be attached to the neck of the retort, sealing all the joints with egg whites and pig’s bladder. A gentle fire should be applied at first, gradually increasing the heat.

The phlegm will begin to distill after three hours, and by slightly increasing the heat, the white, cloudy spirits will start to appear after six or seven hours. When they begin to appear, the fire must be maintained and gradually increased until no more spirits come out, which is evident when the recipient becomes clear and transparent. During this operation, the fire must be gentler than when the Vitriol has not been calcined to redness. Afterward, a reddish, more fixed liquor than the spirit will emerge, called the Corrosive Oil of Vitriol. Once no more substance comes out, and the recipient appears empty and without any cloudiness, the operation is complete. This process lasts four or five days and as many nights. The spirit must be dephlegmed in a water bath in a retort, with a large vessel attached to the neck of the cap. When acidic drops begin to fall, cease and rectify the spirit in the retort over hot ashes. This will cause the clear spirit to emerge, leaving the red oil at the bottom of the retort. The oil must then be rectified by sublimating it in a sand fire. The Volatile Spirit and the Oil are hardly different from each other; they are almost the same thing, with the difference being that the volatile spirit contains more phlegm, and the oil contains less. The spirit is more volatile, and the oil is more fixed; the spirit rises in a cloud-like form, while the oil rises in rays. The best pharmacopoeias explain how to successfully carry out this operation, as its quality depends on the rest of the work.

After this, Mynsicht says to take the dead head left at the bottom of the retort, and after breaking it, pulverize the material on a marble or porphyry slab. Then, place it in a glass vessel, pour hot common water over it, and stir gently. Let the mixture digest for some time to allow the water to extract all the salinity. Filter the liquor through gray paper, and then evaporate all the moisture over a slow fire until a film forms. Place the dissolution in a cold place, where crystals of the nature and flavor of Vitriol will form. Calcine the dead head again by cohobating the crystals that you have roughly pulverized. Calcine everything in a crucible over hot coals, making sure that the flame does not blacken your material, which should remain white. Then dissolve it in hot water, filter it, and evaporate and crystallize as before. Mynsicht advises repeating these operations until the smell of Vitriol no longer appears. Finally, the philosopher says to calcine the dead head for the third time, very strongly but gradually, to extract a beautiful and pleasant-tasting salt that should be carefully preserved as the perfected Salt of Venus.

However, Mynsicht adds that the crystals prepared after the second calcination are of no use for this mystery (sed oleum mysterio minime utile = but the oils are of no use to the mystery). It must be admitted that if the crystals were not necessary, one would have to settle for multiple calcinations and extract the salt and crystals from the last one, which contradicts the very words of the author, who prescribes that as many crystallizations should be done as calcinations. Moreover, the best pharmacopoeias and the most skilled chemists of our time all agree that after the Vitriol has been calcined or rather the colchotar that remains after distillation at the bottom of the retort and after one dissolution and crystallization of the salt, only a black substance remains, which they call the sweet earth of Vitriol. Therefore, if one did not cohobate the crystals (which are truly the Salt of Vitriol) onto the dead head, no more salt could be extracted after the second calcination, much less after the third. This is why these repeated operations are intended only to soften and purify the salt, sweeten it, and make it suitable for composing the Mercury of the Philosophers.

After giving the exact and faithful preparation of the Salt and Sulfur of Venus according to the Chemical Art, one must proceed, and for this subject, one must take pure and clean steel filings, which should be placed in a glass cucurbite. On top of it, pour a portion of the Sulfur or Oil of Venus to soak and penetrate it. After placing the cucurbite on a sand bath, pour the Oil of Vitriol on the filings, adding distilled rainwater that is slightly warm, about five or six fingers high. Stir the matter occasionally with a iron spatula, being careful not to break the cucurbite. Then, after slightly increasing the heat of the bath, allow the substances to digest for twenty-four hours. Afterward, pass the hot dissolution through gray paper and place it in another glass cucurbite in the same sand bath to evaporate any superfluous moisture until a film forms. Let the residue cool and crystallize in the cane. Then, pour off the liquid that will float on top into another glass vessel, having previously separated, dried, and set aside the crystals. Start the evaporation again until a film forms from the remaining liquid. You can, once again, pour fresh Oil of Vitriol over the residue of the steel filings and add as much distilled rainwater as the first time. Repeat the digestion and the other preparations as before to obtain a larger quantity of Vitriol of Mars.

There are some Chemists, following Mynsicht's example, who mix water with the Oil of Vitriol before pouring it onto the steel filings, but the dissolution cannot be done properly in a short time with water, as the spirit acts with much more force when it is alone than when it is weakened by water. Thus (as Charas rightly says), it is much more appropriate to begin the dissolution of Mars with the Oil of Vitriol, which this author’s experience, repeatedly tested, has always resulted in success. It must also be observed that the weight of the Vitriol Sulfur sometimes reaches up to three times that of the steel filings to avoid any mistake. This Vitriol of Mars, thus prepared, has a much greater virtue, strength, and efficacy than common Vitriols.