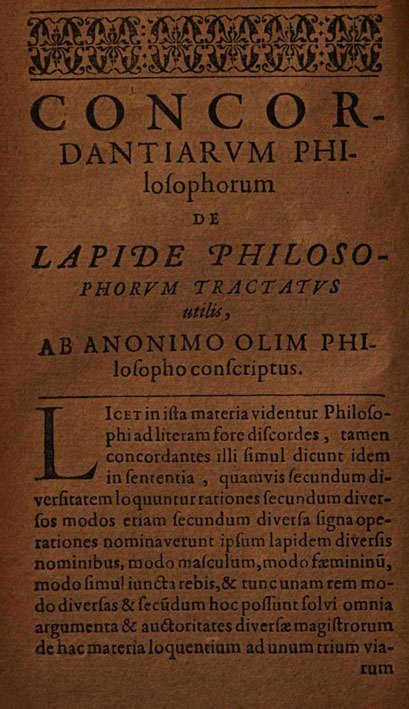

Concordantiae Philosophorum - Concordances of the Philosophers

Buy me CoffeeCONCORDANCES OF THE PHILOSOPHERS

On the Philosophers’ Stone a useful treatise, written long ago by an anonymous philosopher.

Translated from the book:

Harmoniae inperscrutabilis chymico-philosophicae, sive ..., Volume 1

Although in this matter the philosophers seem, taken to the letter, to disagree, yet when in concord they all say the same thing in meaning. For, according to the diversity of the work, they speak their reasons in different ways; and according to the various signs of the operations they have given the Stone itself diverse names now “male,” now “female,” now “the conjoined androgyne” (rebis) thus calling one and the same thing by different names. And on this basis all the arguments and the various authorities of the masters who speak about this matter can be reconciled and reduced to one of the three ways, of which [ways] concerning this Stone we shall speak later; yet in truth there is but one way namely Mercury, whether natural or artificial, that is, drawn out of bodies and of the most perfect [metals].

For in these there is a most subtle and pure substance of mercury, fitter for the Philosophers’ fixation and for all their works than any other mercury in the whole world, as will appear more clearly from the authorities. And thus to each of the three ways that will be described afterwards the sayings of the Philosophers can be most aptly referred, and be understood to mean the same thing; and in like manner, because there are many ways and may be many to the same intent.

Nevertheless, according to the diverse manners of preparations, and the management of the fire as the efficient cause, the operation receives its character; and consequently the Philosophers’ Stone has different names according to its appearance yet all tend to the same end, to wit: to subtiliation (which is called sublimation) and to fixation (which is called incineration or calcination), and it is called by many other diverse names besides.

From the repetition, therefore, of that operation namely of sublimation and of inspissation (thickening) itself, which is naturally followed by incineration, or by the Philosophers’ fixation together with skill in preparing the fire, whether with the one only thing alone, or with other helps (which, however, ought not to enter [into the composition]), all aiming at the same end; and by reason of the swiftness of the work and its attraction, there results the goodness of the work. And with the same thing put into service, if it please to proceed further in weight, it may be done by increasing the goodness, as has been said.

The sayings of the Philosophers are plain enough to one who looks into them. What follows treats of the Matter in particular, and something must here be said of it.

First, certain Philosophers hold and indeed all the ancients of the Philosophers at the outset affirm that the substance of Mercury is most subtle and without earthiness (which would hinder fusion and fixation), declaring that from this there exists the material.

From it, when wholly purified and drawn forth by sublimation as Geber teaches in the Summa, in the chapter on the solar medicine of the third order, where (in the chapters on the Stone) he says it is well known, and in the chapter on Mercury he says that from it there is, and that it is called a tincture he further says that by a method of separation you are to divide the most pure by itself and set it apart. Concerning this Mercury the Philosophers are of diverse opinions, as is evident to anyone who reads their books.

Some have taken this to be the common mercury, yet not simply so, but purified by sublimation, or by other ways of giving it life, and this repeated until it becomes purer without any earthiness whether this be done in the vulgar way, or commonly, or also philosophically, according to what is fitting for the mercury to endure in the fire with its proper tolerance and evenness. Then, by the continuance of the fire, the natures are changed within it, and the subtler part is separated, being raised into the upper vessel, and its earthiness will remain like dregs at the bottom; of which, when speaking further on of this way, we shall say that thus all the mercury is lifted into a most pure substance, and its earthiness will remain in the bottom to be rejected as a certain Philosopher in the Turba says, who, keeping such a manner of working toward our Stone, declares: “We add nothing nor do we diminish, but we remove the superfluous”.

And to keep to this way we are moved by many sayings of certain Philosophers and by many authorities set down in their books plain enough to anyone who looks into them well. For the present I intend to insert here some authorities that tend to this way.

For Senior, treating of the truth of the Philosophers’ Stone and of the single manner of working it, says: If you consider whatever is said in our books about waters, about sulphur, about vinegar and salts, understand nothing but one divine thing, which, according to the diversity of signs and of preparations, is called at one time soul, at another vinegar, at another sulphur.

And he adds: Do not aim at many things, although the Philosophers say that it is a rebis, and a thing conjoined from things; all this is said by way of similitude, as will be explained below. And the same writer says: Our Stone, which is one thing if, however, it shared in other things (though things are from it), we should not call it “our Stone”; for all men share with other things. And he goes on: Some indeed have added sulphur.

Likewise, according to Aristotle, nothing is perfected unless with a subtiliated ferment; and thus there are subtiliation, and distillation, and the Philosophers’ fixation, and incineration because all these follow one another in nature by the sole regimen of the fire, according to the requirement of the work and the degrees of the fire within its tolerance; of which I shall speak more particularly below.

Likewise another Philosopher in the Turba says: Every thing that is bought for a high price is found useless in this art; nor does it, nor should what is said in the seventh book of the Precepts be allowed to stand in the way namely, that “this thing is in every thing.”

For Senior explains it thus: that in this very thing are all the powers, to wit, whiteness and redness.

And Geber confirms the same in his Summa, saying: “It is only in this, from which they are drawn forth; and from it they called this Stone one thing.”

As a certain Philosopher says: “In this alone is everything that it needs sulphur, and salts, and tincture.”

And they say that this thing does not consist in a multitude of things; and they further say that those who intend to labor in this art, if they walk in the right path, should busy themselves about one thing, namely, our Stone. If you say you do not know it, you stray.

Likewise in the same place: do not forget that in this work you need only one thing; do not trouble yourself with a composition of pluralities, about which many envious men speak in figures. For our truth is one, in which is the tinging spirit that we seek, surpassing all natures.

And therefore many Philosophers have called this thing “all things”; and there also it is said that many things are not needed only one thing and thus the work is completed.

Thus are the Master’s words: “Nature rejoices in nature, and nature contains nature; and the wise man by himself rules it and draws from it every nature that excels.”

You will find many more authorities touching this matter in the books of the ancients; let what has been said suffice for this part.

There are also certain Philosophers who place the Philosophers’ Stone in mercury not merely the common sort, but that extracted by skill from the perfect metallic bodies, such as the Sun or the Moon and this method, they say, is to be and is in fact done by means of the perfect bodies, in such wise that those bodies are made subtle and are converted into a true mercury like the natural one.

According to one procedure, the perfect bodies are to be subtilized by the proper ways and means namely by “sharp waters,” and by the water of the salt called sal ammoniac, which greatly subtilizes bodies; and by continuing this subtiliation until the body becomes spiritual, mercurial, and volatile. This body, thus dissolved or prepared, they have called mercury and the Philosophers’ Stone; and then, with this, they proceed by the modes of working to be set down afterward, until from it there is made a tincture capable of being increased without end. And they are moved to this way by a reasonable motive: they say there is no doubt that in a perfect body namely the Sun the tincture is white and red; and likewise in the Moon, in which the tincture is white, and by the continuance of the fire it becomes red.

Others, however, take one part of mercury; others take three parts of the male and five of the female; or, as some say, they take both alike conjoined, male and female, because bodies that are similar corrupt more quickly than a single one alone. And then, when the body has thus been resolved into living mercury, they have within it a mercury purer than any natural one, and also a magistery disposed for physical fixation; and from this everything is made more perfect and more swiftly than with natural mercury provided they operate according to the sayings of the philosophers that will be written below.

And it is not unfitting to affirm as those men will have it who place the Stone in a sublimation carried out in the waters or in the perfect bodies, and not in the vulgar sublimation, but in such a raising aloft and subtiliating of the body that it becomes spiritual, readily entering into fusion, and tingeing.

Wherefore by such a sublimation the perfect bodies are changed from one nature into another and become incorporeal, until by roasting (assatio) they can from themselves beget their like namely, the Sun [begets] gold, the Moon silver and so on without end. And they say this belongs to the perfection of any nature, that it can generate its like. But Nature cannot of herself accomplish this; and therefore they say that the craftsman begins where Nature left off from perfection, and thus that this philosophical tincture is discovered by this most noble secret art.

This way already spoken of yet tending to one thing, to wit, to the most noble mercurial substance, or to a body subtilized to such a degree that it is accounted the same is confirmed by these authorities.

For Geber, in the Summa of the Perfect Magistery, in the chapter on the Sun and the Moon, says: “By God, the tincture of redness is the Sun, and of whiteness the Moon.”

And elsewhere in the same book he says: “The tincture must be more subtle than the bodies from which it can be drawn.”

And the same Geber says that the tincture is in the bodies and in mercury, in these words: “In the bodies more difficultly, but in mercury more easily and more perfectly.”

And the cause of this may be that it is hard to dissolve perfect bodies of very strong composition in such wise that they may be compared with mercury in subtlety and penetration, as will appear.

The same Geber, in the Summa of the Perfect Magistery, speaks thus: To subtiliate the bodies from which the tincture is drawn is a labour for a stiff neck [i.e., very hard].

But that the tincture is more perfect in mercury may be recognized for this reason because a longer toil is required with natural mercury before it be prepared so far as to be in purity and to be made like unto a body reduced into mercury; and, as has been said, a long time slips by, and it needs a long digestion together with the modes of sublimation (as will be said below). Wherefore, since it needs much digestion with the modes of sublimation for its perfection, it also becomes more accustomed to the fire, and thus the tincture is generated most perfectly; and therefore he said that in mercury the tincture is easier and more perfect.

Again, in favour of the way which asserts that the Philosophers’ Stone is in the bodies, the intention of Geber seems very plain in his book which he composed On the Investigation of the Magistery; speaking by parts, he says, in the chapter on the tincture of the third order: For the white Answer: the Moon. For the red Answer: the Sun. And dissolve in aqua fortis and make little stones; then, he adds, from this our fixed body is dissolved into our fixed mercury; which afterward govern by further subliming and fixing, as we have delivered in our Summa.

Here note only this: although Geber says for the white Answer: the Moon, and for the red Answer: the Sun, he does not by this mean to deny that both tinctures are present in each several body by itself, just as in the mixed bodies; indeed the tincture of the white is in the white, and of the red in the red as is evident from a certain Philosopher who says: our Stone, though manifestly white, is secretly red; and conversely, by the decoction of fire.

And Plato in the Quarters adds: “Transform the natures of things, and what you seek you shall find.” Likewise another says thus: “Make the hidden manifest, and the manifest hidden, and you will find the Magistery.”

To this way belongs what the Philosopher in the Turba says: “Unless you make the corporeal incorporeal, and the incorporeal corporeal, you have not yet found the rule of working.”

Likewise the philosopher Aristitanus says: “I advise you to begin from the perfect; for before you could bring the imperfect to such perfection, you would sooner be deprived of life.”

Likewise Hermes says in one of his treatises, entitled On the Secrets of Hermes: “If you consume three parts of your camels” [i.e., a cryptic measure of “camel-dung” heat].

Plato himself agrees with him in the book On the Quarters, saying: “Gold must be brought into vapor; and if this cannot be done in a circular figure, let it be done in a quadrangular.”

This road is also held by a certain master who raised the question about the diversity of this art; and the philosophers suitably say: “Our mercury is not the mercury of the vulgar, but of the wise.”

But they understand this of mercury in so far as it is the Elixir.

Likewise Senior says: “If you melt the white body, let it be received according to this manner of working; if not, leave it.”

Likewise Calid says: “Philosophers past and to come will not be able to make gold without gold.”

And he adds: “This gold proceeds from our gold, and it is the sea.”

And the same Senior further says: “O, if you knew that this our Stone is the sea in which the metals are submerged!”

And again he says in the same place: “Every is the thing of all the Philosophers, which has within itself the whole of what it needs, and is the mother of gold.

And likewise in the Turba [it is said] that it is “more excellent than Nature and the vilest of all things” provided only that gold be not viler than Nature.

Behold how Senior, by his words, seems to disagree, and the other philosophers among themselves, as may be seen from the authorities already alleged; yet nevertheless they all cry out: one thing, one vessel, one preparation, which is sublimation; and this single operation, according to the degrees required of the fire, is followed by diverse operations namely fixation and the thing itself receives diverse names, as was said before.

Now therefore we must, not without reason, approach the concordance of the philosophers. Conclusively, then, it seems we should say that all the philosophers and their authorities agree in this, that the Philosophers’ Stone is always Mercury; and this is plainly evident from the authorities already set forth, and appears most clearly to those who read their books. They seem, however, to disagree about natural mercury and extracted [mercury], as has been said.

First, then, it must be stated that the authorities which tend toward the way of natural mercury are to be understood, and their sayings are not to be taken by way of denial as if another mercury, extracted, were not, or could not be, the Philosophers’ Stone.

Rather, because such philosophers discovered the science also by investigating the mode of decoction in natural mercury, they taught the art in that alone, so that men might not lay out expenses upon more precious things, since in what is cheaper it may also be well found.

Their own authorities, namely: “Everything that is bought at a high price ” as said above, they set forth.

But those who placed the Stone in the bodies did not do so by denying the other way; for it ought to be doubtful to no one that to one and the same goal and intention there are many methods, talents, and paths one easier, another harder, one longer, another shorter yet always willing the same thing. And thus, speaking in this way, they aimed at this: that once mercury of a perfect body is had whether resolved and subtiliated into the most subtle operation of mercury it is certain that this mercury (this thing) is a better mean, more perfect, and more apt for further bringing to perfection, so that it may beget its like from itself and become a tincture and that in a shorter time, with less difficulty in the manner of working and less chance of error in the fire; for many have gone astray working with common mercury, and in preparing it namely, fixing it they have been drawn out for long periods and almost to extremity, which perhaps would by no means have happened to them if they had worked upon perfected mercury extracted from bodies.

Since, therefore, what is perfect is more quickly perfected further and is more difficult to destroy, consequently there is less error since nature rejoices in nature, and is glad with it and befriends it.

A certain Philosopher says: “Where things have a common symbol, the passage is easy.”

And this is a noble authority in this art with respect to the unity of our blessed Stone; for by it many ways are excluded, in which many toil at the conjunctions of bodies and spirits by amalgam and in waters, etc. whether by working at bodies with bodies; and they wished to turn the body into spirit, and afterwards to fix together one body with a spirit, or one spirit (or several) with a body, or both perfected together saying that no tincture can be made unless there be the marital conjunction of the Sun as the male, the Moon as the female, and Mercury as the mean that unites the tincture. Such sayings are set down by many authorities that write of distillations, etc.

But since the Stone is one, as all cry out, and “has within itself the whole of what it needs,” and since, according to the various signs in its preparation, it is called by many different names (as I wrote to you earlier in this treatise), it is no wonder that those who in this manner labor upon “bodies of bodies and spirits” find nothing for long periods.

For the less simple and the more composite a thing is, by so much the less common symbol it has in this art, and therefore the harder the passage. For the work requires subtiliation and the due degree of fire, which can hardly be applied to things of diverse natures that are to be brought to one: perhaps while one is being fixed, another becomes volatile; or while one is being made subtle, another perhaps is thickened which ought rather to be subtiliated according to the authority previously alleged.

Yet it is quite true that spirits joined to bodies by solutions in sharp waters, or by amalgams with a body, or by other methods and thus, when those spirits have been digested with perfect bodies, either by themselves with solutions, or by roastings or putrefactions, and again by solutions with waters and salts, with alums and other contrivances of which many devices are written in the books of Geber and others, On the Investigation, on medicines of the first and second order, and in other practical books to be consulted there.

The spirits themselves are fixed in bodies, and thus they can do well in particulars in medicines of the first and second order; perfect augmentations can also be well effected, and imperfect bodies can be well cleansed by their calcinations and solutions and by the roastings of spirits, which are turned from imperfection unto perfection; since the metals themselves, according to Hermes, Empedocles, and the Sigil, differ only as more and less, and not by differences and forms of species. But of these particular methods there is not much to our present purpose; therefore look into other books on this matter.

From the foregoing writings it plainly appears that all the philosophers with one accord affirm their Stone to be mercury not the vulgar, but ours: whether this mercury be natural and so purified (and this will not be the vulgar’s, but the philosophers’), or whether it be from a body, or even extracted from perfect bodies, in whatever way and by whatever devices, either by itself or with additions for shortening the labor provided only that the mercury extracted from a body be subtle and not deprived of moisture, but a pure body subtiliated in the likeness of mercury, and provided further that the additions do not remain within it.

But then the Philosophers’ mercury itself is prepared to subtlety with instruments and with fire, as the efficient cause, according to the methods and devices of Geber who, in a few words, told the whole truth of the matter and of the other philosophers who agree with him, together with the urgency of the work. And it is thus prepared so that from it a true physical tincture can be made. By this, moreover, one may meet the authorities written here and there in the philosophers’ books, to which the reader who considers them may refer the passages set down here.

Let these few remarks about the substance and essence of our Stone suffice. What follows is

On the second principal point, namely, on the preparation of our Stone and the regimen of the fire in particular, something must be explained with testimonies of the ancients. In this matter the first method is chiefly to be noted. Geber sets it down in his Summa in few and true words.

Therefore, as it seems to me, and according to all the philosophers, one should work thus: take the Stone from the aforesaid [materials], now well known, and prepare it in a single glass vessel without another or in a vessel upon which there is another vessel in the fashion of a cucurbit and an alembic, yet without a beak (that is, a blind alembic); and let them be masterfully joined if you work “vessel upon vessel,” as certain philosophers say, as I shall afterwards write so that one does not look away but attends continually which is the work of subtiliation, so that it may be subtilized perfectly, and thus come to the uttermost purity and this with urgency in the work and with a greater tolerance of the fire, by continuing the work of sublimation continually and very successively for a long time.

The reason is this: the whole magistery, as all the Philosophers will, lies only in subtiliation; through the continuance of the fire and its tolerance all the other properties follow naturally namely, once the subtiliation has been made there is inspissation (thickening), and then incineration of at least some part, and from this there consequently follows fixation.

And no one ought to doubt that fixation and incineration belong to sublimation itself, by a stronger fire, as will be said below. The same portion, because of the parts not yet fixed, must be sublimed again, and this must again be fixed, and again sublimed according to the precise intention of Geber; and, with itself alone the Stone alone, the fire alone, and its own single vessel, if you please thus the whole Stone will be perfected into a tincture. Nor should you be moved by the notion that some aids are necessary in order that the mercury itself be subtilized in this way, since it is of a homogeneous and very strong composition and especially the Sun and the Moon, if their mercury must be wholly extracted and thus subtiliated into mercury; for this is very difficult and can for that reason drive the operator to the utmost extremity.

To the first point I say: although natural mercury, or even the Philosophers’ that is, of perfect bodies is of a most strong composition, nevertheless by the continuance of the fire some part is always separated by subtiliation from another, as it were in the manner of a vapor; and that part which cannot “breathe” in the vessel grows thick and descends again, and by the due regimen of the fire, that is, a gentle heat, as the intention of the operation requires it subtilizes some other part, and an even subtler one, and so on thereafter until the whole work is completed.

Such is the intention of certain philosophers who write truly of this art; yet other ways (of which we shall set down some below) are not thereby denied, since they likewise tend to the same end of the philosophers in their manner of working, though by other methods and devices.

But as to the second point namely, concerning perfect bodies, as was said above I admit that it is very difficult for such bodies of themselves to be so subtilized and digested that they are converted into the nature of mercury; and perhaps a man’s lifetime would not suffice to await such a sublimation by itself. Yet since it is not impossible (for whatever is generable is corruptible and alterable indeed in itself, and consequently by art and by the administration of the fire, that is, by the heat of the fire and by putrefaction), even a composition however strong can also be altered, and consequently well subtilized into mercury.

Nevertheless, on account of the length of time, it is not unfitting to assert how preparations with extraneous things may rightly be admitted namely salts and sharp waters, putrefactions, solutions, roastings, and calcinations, and whatever others so that the perfect bodies themselves, which are the philosophers’ bodies, may [be converted] / are subtiliated into mercury, or are prepared into the nature of mercury; and then such added things are removed. And when the bodies have first been prepared to so great a subtiliation into mercury, the Philosophers’ Stone is thus named the thing with which, as it were at the beginning, one proceeds, namely living mercury; for, according to the philosophers, one must go forward thus and in no other way. And this is the agreement of all the philosophers, as has already and often enough been shown from their sayings.

But as regards this point namely, the manner of subtiliating perfect bodies into the nature of mercury there is one way of working, just as with the common mercury when prepared (that it may be called the philosophers’ [mercury]), as was said above.

Some have taken up such a method of working and said that it is according to the intention of the philosophers namely of Plato in the Quarters and it agrees also with Geber’s intention (as has been said) and with that of other philosophers. They intend that one should work thus: they take perfect bodies, such as the Sun [gold], subtiliate it with sharp waters, convert it into small stones, dissolve these in slime/lye, and then by roasting congeal them; and they call that operation subtiliation.

They repeat the solutions and congelations so many times until the whole is subtiliated into the nature of mercury, so that it flows with easy fusion and endures the fire; then again, as a fixed part, and they keep the ferment again with four parts of the body, [reducing it] into mercury itself, soluble namely the little stones reduced; they cook it and dissolve by roasting as before, working continually until again the matter tinges; and they say it can go on to infinity for multiplication, and likewise proceed in goodness.

Others subtiliate the perfect body by another way, namely by calcination and with the water of sal-ammoniac, or some other solvent, and then by assation, and again by a like repetition of the work thus laboring by subtiliating until the bodies themselves are in the nature of mercury, whereby they are converted unto a perfect tincture.

Certain others intend to make this subtiliation with sharp waters, by decoction with mercury (sublimed or living) or with other spirits, joining these to the body, and then either by the spirits themselves, or likewise by subliming; and they say that some part of the body is lifted with the spirits.

They continue until they have a good part of the body thus converted into spirit; and then, by separation with a gentle fire, they take upward by sublimation the upper part, while another part, they say, remains in the bottom. The fixed part again, together with the not-fixed part, they in good quantity (or in part) lightly roast and decoct until again the part is fixed and turned into fixed earth. They continue this until they have fixed a good portion, and they say that the earth is sufficiently prepared then they again raise up that earth together with a quantity of the unfixed part; and this they do again until the whole has been lifted; and thus they fix it again.

And this, four times repeated, they say will make the tincture, according to the sayings of Geber, and likewise of Hermes in the Thelesin, who says: “Thou shalt separate the earth from the fire, the subtle from the gross, gently and with great skill; it ascends to heaven, and the two run back to the earth, until it holds the power of the superior and of the inferior.”

And these words of Hermes can very well be brought into agreement with the method of the Philosophers’ Stone spoken of before, and with its manner of working as was said above namely, concerning the philosophical mercury. Hence, to satisfy their opinion which does not seem unreasonable, since it likewise aims wholly at the sublimation of mercury and at making it mercurial.

I say that such modes of working are indeed to be accepted, provided however that in the work care be taken that the bodies be not scorched in such subtiliation, nor the matter be dried too much and wholly stripped of its own nature. For, as was said before, whatever bodies, or mercury, are subtiliated by whatsoever way so long as such preparations and decoctions, etc., are made according to the way of the philosophers and their intention (of which mention has been made above, and will be made in the following parts of this treatise), whether there be one or more ways and methods tending to the same end just as before it was determined concerning the concordances of the philosophers about their Stone.

Yet it is true that one must by examining the sayings of the Philosophers; and, as is written in this my treatise, the philosophers incline more to the way that lies in prepared natural mercury, or in living mercury extracted from bodies, than to the ways just set out above. For the ancient philosophers tend more to the unity and uniformity of the thing and of the work than to those newly prescribed ways and to multiplicity; since in one thing there is a greater unity and a stronger “symbol” (that is, uniformity) than in many, and consequently the work is easier and less liable to error provided only that the manner of the fire and of the preparation, which all the philosophers have greatly concealed, be rightly understood.

Nevertheless, for the completion of this treatise concerning the intention of the Philosophers’ Stone and its way in which the chief philosophers understand their sayings some useful matters about its regimen, according to what is written, should be considered in regard to the Stone of the philosophers, which consists in one single thing and one single work. I therefore propose to write again, and thereafter to confirm these matters by the authorities of the philosophers, and so finally to conclude this treatise.

Accordingly, as in the second principal part of this treatise something has been said about the preparation of our Stone, I now conclude and declare absolutely that it is to be affirmed solely as to the mode of preparing the Stone to which the philosophers principally intend, so far as, from my writings, you can now learn the whole [process] of the Stone’s preparation consists in sublimation alone; and by this operation by the long continuance of the work, with steadiness and urgent attention to the Stone, and by the regimen of the fire according to the intention of the work and the tolerance of our mercury the whole magistery is completed.

All the various operations that are written of (on account of different ways of governing the Stone) follow naturally: after sublimation comes inspissation (thickening), then incineration, then ceration, and our physical fixation. And that you may better understand this last term, physical fixation: one must above all beware lest the Stone, together with the strength of its fire, be deprived of its moisture; for then its own moisture can rarely or never be restored, and so the whole work is ruined as has happened to many philosophers, who even knew the Stone well. For this reason they denied the art; and others too, who wished after them to deny the art, went astray not attending to the fact that all the philosophers cry out that their work is sublimation.

But they, having in some measure subtiliated and purified the Stone known to them, then aimed at fixation, abandoning sublimation; and when the purification was complete they fixed the Stone again, whereby they deprived it of its moisture, and by this they were brought to the utmost disaster failing to notice that all the philosophers proclaim: one body, one labor; which is followed by the divers different signs, according to the uses of the Stone and its various dispositions yet all of this consists in sublimation alone, under the government of the fire.

From that regimen there arise different operations upon the Stone: now subtiliation, now inspissation (thickening), now incineration by a fire suited to its tolerance; thereafter there follows the hidden physical fixation.

Therefore this physical fixation must be considered with the greatest care namely, that at the moment when the Stone is being fixed, the power of subtiliation belonging to the fixed part be not taken away from the part that is to be perfected but is not yet fixed. And such works are to be done in one vessel or in two, as was said before, and as one continuous labor with the proper manner of ministering the fire: first, the sublimation of the Stone; next, through a greater tolerance of the fire, inspissation; then incineration of that part which by nature and by the continuance of the fire and the magistery is made fit for fixation; then, consequently, let it be fixed by physical fixation, as was said above. And let the whole work be carried on as one labor until, with the signs to be mentioned afterward, the thing itself stand in perfect magistery.

Here, however, it must be noted lest I seem to the envious to have omitted it why I have not written precisely the scale of the degrees and properties of the fire. I say that it cannot be determined very particularly about such degrees of fire and their proportions, nor have any of the philosophers set them down so fully, although one has said more than another on this subject.

In the rest, industry and practice to the exercise of those who labour; from which, among the authorities of the Philosophers who speak on this matter, some more noble points may be drawn. For as from the sayings of the Philosophers I can gather the whole regimen of the fire by degrees, and the preparation in this very Stone, consists herein: that our Stone, being one, be kept in one vessel, as is written, and with a gentle fire be held and made subtle, and that a part of it be separated; and let it remain in the fire for a good space of time, so that no other task of the work namely inspissation be too quickly pressed upon it, until by the long continuance and habituation to the fire you see that part, by an equality of fire, thicken of itself by nature.

Then, by slightly strengthening such fire continually, until you observe some part tending to incineration, give the fire greater vigour yet not departing from the first work, nor in the second by any violence of fire and, some part being now incinerated of itself and naturally, by reason of the multiplication of the other subtle parts, let that same part be made subtle again; and so proceed continually, as was said, and this with a greater tolerance of the fire, until this be done many times, namely by subliming, incinerating, &c.

And you will find that this work is at the first a fixation by the long decoction of the Stone in the fire. Our Stone will come to such a tolerance of the fire, that as great a fire is required in the second work the labour that is set upon the Stone for its steadfastness as at the first for inspissation; and so, consequently, for incineration and fixation; and this continue governing thus until at last the whole Stone, with its due preparation namely the purification effected by such a way of ruling the fire over the Stone affords easy fusion at its own ignition, and solar-work and lunar-work (old masters’ terms) and, on sound proof and trial, transmutes the metals or mercury, whether entirely or in part.

And I say “or in part” deliberately, for it is no matter if all your material put in has not been prepared to the same degree; indeed it does no harm if some portion of it remain under some regimen namely, in sublimation or in incineration. The reason is that this is a sign the Stone has not been driven on with haste and that is better.

Rather, with the greatest care one must beware lest the Stone be digested so quickly that it be in some way deprived of a prior operation or of the earlier works; for the Philosophers’ sublimation is to be continued a long time over the Stone, since it is not only an elevation upward, but also a remaining beneath. And when this is accomplished, thus the whole magistery is perfected which test by projection upon a body.

If then you find the Stone to be so whitened and purified that it gives a pure whiteness, and then you see the Stone to be so whitened and made subtle that it penetrates to the nature of the thing to be tinged, then penetration having been made if the Stone be fixed so far that the thing proved stands firm to every trial, you have laboured enough.

But if not, repeat again upon the thing the first work, and so in order as it is written until it be accomplished, God assisting.

Behold, now it may be affirmed that it is a very great error to bustle the operation of the Stone in such wise that, while one operation is intended, another is taken up and the first is abandoned. For if the magistery be not brought to completion as happens with many, who on this account are driven to extremity in this art you could not then repeat the first work upon the thing itself, and the business would be utterly ruined. Otherwise, however, if you shall have well and carefully amended, according to what I have written for you concerning the regimen of the fire, the work cannot be destroyed to that degree.

And if at the first view you do not find [what you seek], yet by assiduity in the work, as I have said, you can very well repair your defect; and thus you may not only make good or reform it, but even resume the exercise of the work again with the unfixed part, and by labour, as before, bring the work to perfection just as Geber says in the last chapter of his Summa, that the magistery of the Stone may be multiplied infinitely in increase and in goodness.

Now, moreover, I will not omit to insert a few authorities of the ancients in confirmation of the foregoing, concerning the regimen of the Stone with respect to the preparation of the fire itself, committing this to the diligence of any reader of the philosophers’ books.

For Senior, first treating of the preparation of the Stone and of its regimen of fire, says thus: “The preparation of our Stone is difficult, and most secret.”

Likewise in the same place he says: “The vulgar, having their eyes asleep; for even when they have it, they do not know its preparation.”

Likewise the philosophers say concerning the fire: the fire must be of the heat of the Sun when it is in its proper state, and therefore they called it putrefaction.

Likewise, in the same place: let your fire be the fire of baths.

Likewise, in the Turba: let your fire in the whitening be gentle; and at the time when the tincture is to be brought to white, a greater tolerance of the fire is required.

For when the matter of the Stone begins to grow red through the mere urgency of the work itself, then, when the Stone is worked toward red, in the first operation there is required only such a degree of fire in the red as was required for the third degree of the whitening. And herein a man must be cautious not to govern the Stone with the degrees of fire that belong to the red before the time of perfect whitening, until the tincture has been perfected under the white regimen.

On this the Rosarius cries out, saying: “Do not mix the work of the white with that of the red.” These matters, however, must chiefly be left to the experience of practitioners.

Likewise in the same place: when our Stone is set in its vessel, a gentle fire must be made for forty days, because by it the corrupting moistures are drawn off. For he commends the length of the work, and blames haste and such burning as makes it impossible for the Stone to return to its first work and be perfected in the whole.

Likewise, in the same place: we must beware concerning our “vinegar” that it be not turned into smoke and perish through the violence of the fire.

Likewise, the Turba says: In our work all things are first blackened that is, when the matter is incinerated it is not yet perfect. In the second all things are whitened that is, in the second operation the matter is disposed toward whiteness and clarity. In the third the whole composition must be incinerated, always together with a perfect whitening, so that the body be not wholly incinerated unless it be perfectly whitened, as was said above.

Likewise it is said there: “Do not despise the ash.” For again its sweat or liquefaction that is, sublimation or solution (which here are the same) is restored to it by a stronger expression of the fire; and by this the crown of the fourth fire and the tincture are perfected.

One must know that sometimes after the blackness the matter becomes yellow, and sometimes red before the whitening. About this one need not be anxious, except that such a state does not contain perfection as has been said because it would mix the red with the white, which must not happen. Rather, the degrees [of fire] must be moderated when you see such an effect, so that one does not depart from the intention which I have now made most plain to you namely, to direct the work from blackness to whiteness, so that the work may always be able to return to its principles.

Whence Hermes says, and simply in the Turba: “At the beginning let crude and fresh mixtures be taken; let them be purified and mingled, until the elements are joined together and held together not by grinding with the hands” (as the Turba says above), but let them be washed with water, which they then conceive.

Then draw them out and nourish them, so that the offspring may be produced; and he adds: Know that this dispensation takes place in the putrefaction at the bottom of the vessel not with the vulgar rotting, but by incineration; for the ancient philosophers nowhere set down anything about putrefaction or the distillation of waters, unless perhaps allegorically and figuratively.

The offspring, however, is in the air, that is, in the upper part of the vessel; it will be sublimed with “vessel upon vessel,” as Senior seems to understand of which more below.

Likewise in the same place it is said: Take them from their minerals, and raise them to the higher places of the mountains, and weigh/measure them on the mountain-top, and bring them back upon the root.

And these are plain words, written without any envy. From this authority some have wished to draw this method of working: they convert purified mercury in water by roastings or by being driven together with other things or by itself; they distill through an alembic, and water the earth in the bottom with the distillate, and thus turn the water into earth; and they say to continue in this way until the perfect tincture is accomplished.

Whatever be the case with this in what follows or has gone before, it does not seem to me to have been the intention of the ancient philosophers although I do not altogether disapprove that way, since in some places they seem to proceed by preparations of mercury, sublimation by way of purification and fixation through its own natural moisture does not, taken literally, seem to agree with the philosophers’ practice; for others say: “Our water is not the vulgar water nor rain,” and by this is explained what the philosophers meant when they said: “You must divide our thing and turn it into water, and into vapor, and thicken it again.”

Likewise: “It is no use to you to sublime water back out of vapor.” Many such sayings are to be taken allegorically.

Also the philosophers in the Turba say that the beginning of our operation is this: that the Stone be worked with a gentle fire, so that it likewise be made dead, and first its soul be restored to it and this must be continued so that the soul remain in the fire.

Likewise, according to Geber, in its preparation a threefold fire is required: first, very mild, so that the substance of the Stone does not rise, but only vapor; second, that some substance may rise and the vapor begin to thicken; third, that a part be incinerated, according to the magistery already described.

Likewise Senior bids that, when their One Thing to which we add nothing and take nothing away has been sufficiently purified (here he speaks of mercury, natural indeed but purified from earthiness, that is, the philosophers’ [mercury]; whereas the other philosophers’ mercury made by the resolution of a perfect body, as is said, is said to need less of such purification), then the Stone should be divided into parts; and he says this according to the opinion of those who work with more than one vessel either with a double vessel or with a vessel set upon a vessel so that the matter may be digested more surely and better, the aim of the art and of the prepared fire be met, and the work be finished more quickly.

Yet the same operation tends to the same intention: namely, to fix a part of the Stone and then to subtiliate with the part not fixed, as I wrote you before. Nevertheless, these things can also be done in a single vessel and with one thing only that is, with natural mercury, sublimed and artificially purified from earthiness and each step can be carried out most excellently.

Master of this operation was Antonius, in his book of the Concordances of the Philosophers, speaking thus: “Let purified mercury be taken I say the same and even better as was said previously about the mercury of a perfect body, and better still of the most perfect, namely of the Sun and let it be placed in its vessel, as has been said, and be dissolved into most subtle parts like unto vapor; and then let that vapor be thickened.

And so let the work upon the very Stone be repeated and continually continued, according to the devices and methods of the ancient philosophers and, clearly for you, according to my doctrine written in this treatise until the whole work, with urgency and continuance and by its own reiteration, be perfected, with the help of the Most High, whose name be blessed for ever and ever.

Amen.