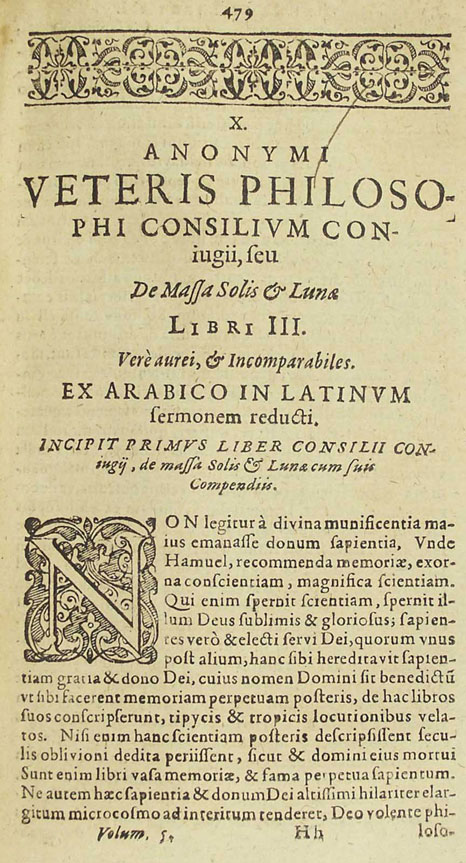

The Counsel of Marriage of an Anonymous Ancient Philosopher, or Concerning the Mass of Sun and Moon, in Three Books

Listen Audio Book Buy me Coffee10. The Counsel of Marriage of an Anonymous Ancient Philosopher, or Concerning the Mass of Sun and Moon, in Three Books.

CONSILIUM CONIUGII, SEU DE MASSA SOLIS & LUNA

Truly golden and incomparable.

Translated from the Arabic into the Latin tongue.

Here beginneth the First Book of the Counsel of Marriage, concerning the Mass of Sun and Moon, with its Compendiums.

Translated to English by Mitko Janeski from the book: Theatrum chemicum Tom 5.

No greater gift of wisdom is read to have flowed forth from the divine bounty. Wherefore, Hamuel, commend it to memory, adorn the conscience, magnify knowledge. For he that despiseth knowledge, God most high and glorious despiseth him. But the wise and chosen servants of God, each one after another, inherited this wisdom unto themselves by the grace and gift of God, whose name be everywhere blessed. They would make perpetual remembrance for posterity, and of this wrote their books, veiled in typical and tropic expressions. For unless they had described this wisdom to succeeding ages, it had been given over to forgetfulness and perished, even as their masters died. For books are vessels of memory, and the perpetual fame of the wise.

Yet, lest this wisdom and gift of the most high God, graciously bestowed upon the microcosm, should tend unto destruction, the philosophers and prophets, masters of the sciences, willed, with God’s ordinance, that the series of this wisdom should be deposited in writings, but veiled, for many causes.

The first is in the Elder Hamuel: that they might attribute it to the glorious Lord, that He should reveal it unto whom He would, and withhold it from whom He would. For, as Morienus said unto King Calid: O good king, thou oughtest to know, that this magistery is nothing else but the secret of secrets, and the mystery of the most high and great God. For He Himself committed this magistery to His prophets, whose souls He hath placed in His paradise. And if the wise men who were after them had not found their dispositions concerning the quality of the vessel wherein they wrought, never could they have attained unto the perfection of this magistery. And in the same book it is afterwards said elsewhere: Know thou, that the intent of every man who inquireth into this pure and divine science ought to reckon it nothing else but the gift of the most high and great God, who commendeth it to His servants, whose name be blessed.

The second cause is in the Book of Lights of Rasis: after he had taught many things concerning the disposition of the art, he saith: Although all things have been clearly set forth, yet I judge it meet that the lights be wrapped under the guise of enigma. For if I should unfold all things as they are, there would remain no place for prudence; the foolish would be made equal with the wise; nor under the circle of the Sun or Moon would any mortal, straitened by poverty, abandon his middle labours.

The third cause of this revelation is read: lest occasion be given unto the wicked and perverse. Therefore this science is hidden in obscure words, though it ought not to be concealed from the worthy. A certain one of the philosophers, fearing the Lord, said continually: Not so sublime nor so precious did we esteem this magistery. Nay rather, they were minded to write their work plain and manifest. But they trembled to do so, lest it should destroy the world, and the work of tilling and sowing plants should perish. Therefore not without cause wrote they their books veiled, nor compiled them confusedly.

The fourth cause of obscurity is read at the end of the Turba Philosophorum, where it is said: Unless the names were multiplied in this art of ours, boys would deride our wisdom.

The fifth cause is that of the Philosopher of the World in the Turba: For if the vulgar sellers knew this mine, they would not sell it at a cheap price. And if kings knew it, they would not suffer it to come unto the poor.

The First Part of this Book

The Sun, as Algazel saith, is the eye of the world, the splendour of the firmament, the beauty of heaven, the traveller of the spheres, the fountain of all heat, the ruler of the planets, the divider of the hours, the grace and honour of God. The Moon, as Aridem, is the purple of heaven, the follower of the Sun, the solace of navigation, the bountiful nurse of dew, the sign of storms, the mistress of moisture. The Sun is so called, as shining above all; the Moon, as shining with borrowed light, for she shineth not of herself, but all her brightness she borroweth from the Sun.

Hermes saith, the Sun is also the lord of bodies and of stones, and is more noble than they, for he is their king and their abundance. The earth corrupteth him not, nor water, nor fire; he is not diminished in the fire, but the fire rectifieth him and moisteneth him; nor do corrupting sulphurs consume him, for his nature is equal, clear, and rightly tempered. For this cause the wise have exalted him and magnified him, and in him have placed the composition of the great Elixir of the Stone, for he is a substance equal, permanent, and fixed in the length of eternity.

This Elixir indeed is of the complexion of the substance of gold, for it is hot and moist; and this Elixir is in bodies as the Sun in the stars. Wherefore the Sun is king of the stars and their light; and by him are fulfilled the things of the earth, of plants, fruits, and minerals. For he retaineth every body, and is retained of them; he is the ferment of the two Elixirs, the white and the red; and they are not rectified save by him, nor completed by any other, as dough is not perfected save by leaven. And this leaven is in the Elixir as the rennet in milk, and as musk in a sweet odour.

The Moon, truly, the bride of the Sun, is of a heavenly colour, near to the complexion of the Sun, and is the mistress of moisture, from whom all things are generated by the help of the Sun.

Mercury again is the lord of metals, who discovereth gold and silver and gems, wishing to lie hidden in the clay for the merchants. Mercury is the part of the matter of all metals, and is of a nature earthy, subtle, moist, airy, inconstant, vehement, and most excellently mixed universally, only inclining toward watery humidity; whence, by reason of its moistening humour, it floweth in cold, seeking a strange path, and flieth in fire. By reason of its airy humidity and vehement complexion, it is not burnt, but wholly sublimed.

For the airy humidity, moved by the fire, carrieth with it its subtle dryness entirely, so that it leaveth behind it no dregs. And by reason of its dryness it floweth in globes, and doth not moisten what it toucheth, nor cleaveth thereto, by reason of its most vehement complexion. And by the solidity of its dense parts, being deprived of rarity, it is weighty; and upon it swim stones and all metals, save gold, which seeketh the bottom. From this thou mayest draw the greatest secret, namely, a nature, symbol, and great similitude.

And it is to be known, that the Sun and Moon and Mercury are digested by a temperate heat; but Mars and Venus by a fiery heat, exceeding temperance unto burning, and this heat is called contrary. But by the heat molendesi the defective resteth, and in part thereof are Jupiter and Saturn digested.

Know also that pure Mercury, that is, most excellently tempered, is found in the Sun and Moon, and is seen to dissolve itself, although it be matter, or rather a part of the matter, of all others. And when it is brought by nature’s benefit unto its own species, by reason of its most excellent complexion, it can no more be corrupted, but other corruptible metals must be generated from it. And it abideth in process, so long as it is in becoming, not in being, namely in digestion, optessi and molendesi. By these, and through these, the wise prepared their Stone from the best ore they could find.

Whence Geber, who was ignorant of the first principles of nature, is far removed from our art, because he hath not the true root on which to found his intention. But he that hath known the principles of nature, and the causes and essences, yet hath not attained the true end and perfection of this most hidden art, he hath nevertheless an easier access, and is little removed from the entrance of the art. He who hath known all the principles and causes of minerals and their manner of generation, which consist in the intention of nature, is scarcely far from the complement of the work, without which our science cannot be perfected.

The Stone of the Philosophers is a king descending from heaven, whose mountains are of silver, and whose streams are golden, and the land of the Stone, and precious gems. Behold, all the kinds of the art are now enumerated.

The Constant One saith: Know, my son, that the work of the philosophers and of the prophets is in nothing but quicksilver. For they, pondering on all things, and arriving at the knowledge of quicksilver, determined that they should take quicksilver, whereby they work. Therefore, in natures and in accidents, which alter all things, they have repeated their thought and their mixture. When therefore their intention rested upon their Stone, and they knew that from this Stone proceedeth quicksilver, which some of them desired exceedingly to hide, they named it by all names, and likened it unto every work and thing.

Some indeed by only one name, which is the Stone. The water, truly, that is drawn from it, or from her, or from him, they called quicksilver. And this they divided into two parts, which it was needful they should call by two names. Some called them heaven and earth; some male and female; some stone and water; some spirit and body; some egg and cock; some man and magnesia; some vile and precious; and so forth, even unto dung, which scarcely may be attained, which men and boys tread underfoot in the streets and ways, that is, the moist thing—whose exposition shall appear in what followeth.

Whence Rasis in the Light of Lights: some wise men said it consisteth in one thing only, namely in the moist; some in two, male and female; some in three, spirit, soul, and body—that is, water, earth, and tincture; some in four, namely the elements.

The Wise, nevertheless, do say that the five elements spring forth from one root, namely the philosophical air: to wit, the four elements—hot, cold, moist, and dry—and the fifth essence, which is neither hot, nor cold, nor moist, nor dry, without admixture of any other kind. For it dissolveth itself and coagulath itself, it maketh itself white and is adorned with redness, it maketh itself yellow and black. Moreover, it disposeth itself, that is, it becometh as the pledge of wine, for nature rejoiceth in nature because of likeness, that is, the nearness of nature between them. And from itself it conceiveth, for one is the kind of all those species, namely male and female, and the spirit of the Moon. And nature overcometh nature, and nature containeth nature, until it hasten the end of the work.

Adomati, know ye, that there is but one thing, which hath father and mother, and its father and mother are found therein and agree, nor can it differ in aught from its father and mother. Hermes: Its father is the Sun, its mother truly the Moon. And the Constant One: Its mother is a virgin, and the father knew her not carnally, therefore is the generation chaste. And Hermes again saith: It behoveth the thing to be of near kin by nature. And forthwith he addeth: But moisture is of the dominion of the Sun.

And Dantinus saith: That every thing of this art is not, save by God and with Him: for every tincture proceedeth from its like. And Arctotienes likewise maketh mention, that three substances suffice for the whole magistery, namely, the white smoke, that is, the quinta vis, that is, the heavenly water; and the green lion, that is, the brass of Hermes; and the fetid water, which is the mother of all things, from which, and by which, and with which, they prepare it in the beginning and in the end.

These three species therefore, and their preparations, reveal thou to no man. But fools are wont to seek this magistery in every other thing, and in seeking they go astray, for they come not to its perfection, until Sun and Moon be reduced into one body; which never shall be, save God willeth it.

And Aristotle, in his Epistle to Alexander, saith: That there are two principal stones of this art, the white and the red, of marvellous nature. The white, at the setting of the Sun, beginneth to appear upon the face of the waters, hiding itself until midnight, and afterwards sinketh into the deep. But the red, contrariwise, worketh: for it beginneth to ascend upon the waters at the rising of the Sun until midday, and afterwards descendeth into the deep. And in another Epistle he saith: The instrumental water in the art is understood to be twofold, whereof the one is appointed to the Sun, the other to the Moon. And now hath he laid open the celestial secret. And Kalid: In these two stones which I have designated is the perfection unfolded of the four natures: the one is the man, that is, the Sun; the other is the woman, that is, the Moon. And Hamuel commenteth: This is the noble magnesia, commended of all the philosophers, which under many names is one thing, and they are two divine waters, the lunar and the solar, neither of which worketh without the other.

And Hermes saith: That the Stone is the whole secret, and the life of every thing, and every man hath need thereof.

And this is the water which is in the seed of wheat, and in the olive oil, and in the gum of peaches, and in the fruits of all trees diverse; and the beginning of man’s generation is of it; and it is the living thing which dieth not so long as the world endureth, for it is the head of the world, that is, the humour. Rasis, in the Book of Lights, deemeth it superfluous to name and designate it, for it never departeth from thee; for if thou diest, it dieth with thee; and if thou perish, with it thou goest down to death.

And in the same book, of the art of minerals, he thus speaketh, though with much diffuseness: Oil receiving colour, that is, solar splendour, is sulphur itself: even so likewise is brass. Therefore Plato saith: Every quicksilver is sulphur, but not conversely; and every gold is brass, but not every brass is gold. Text: But every oil is likened unto the Sun and unto gold. Therefore Hermes: Fatness is of the dominion of the Sun, and moisture of the dominion of the Moon; for all cold oil is moisture, and all hot oil is fatness. Text: And in respect of death in the second degree, from it is oil pressed, but by reason of the dryness of the earth, after all the vapour of the air is drawn forth into water like unto itself. It is also called the work of death because of rust.

Whence Theophilus: I tell you, iron becometh not rusty save by that water, and it is that which tinctured the plates. And Donellus: But I say unto you, take iron, make plates thereof, afterwards sprinkle them with venom, and set them in a vessel whose mouth is well closed, &c.

And by reason of the ingress appearing in the first and second work it is called Mars. Whence Florius: Know that the first blackness is of the nature of Mars, and from that blackness is born the redness which overflooded the blackness, and ordained peace fleeing and not fleeing; for Mars is the god of war. Text: That which is six, that is, blackness and tincture, is emitted; it is called the perpetual and incorruptible water; the dregs themselves, when they blacken, take unto themselves the name of magnesia.

Gloss in the Turba: Wash until the blackness go forth, which some have called coins. And Gradinon saith: When the things of our art are once ground and cooked, ye shall find blackness; and that is the lead of the wise, of which they said: our coins are black. Text: The white dregs are called white lead, that is, tin. This is ascribed to Mercury, and is the oil, which, being prepared with more worthy administration, they call viscous gold and atrament, and red gum, and red orpiment hath taken to itself the name, because it is the fatness of gold and its whole tincture.

Text. Nature itself, the Fifth, is that of Venus among the Philosophers, which is neither hot nor cold, neither moist nor dry, but a mean. The same is also called the yellow auripigment, and Iris, for its manifold colours. For it is the Stone from which proceedeth every colour; it is the perpetual water, white indeed when first it appeareth in candour, then also the white of an egg, and vinegar, sea-water, almidzari, and other such names attributed unto it.

From this water, and from this body, quicksilver is transformed: and it is dried, turning itself to red. Thus this oil of the hidden and secret is in the white of quicksilver, which, as hath been said, confirmeth the beginning and root of the whole work. And when it shall be perfected, being set upon tin, or lead, or brass, it converteth them into the best species of silver. The same moreover may afterwards be brought forth from the tincture of gold. And finally, becoming red, the oil, namely sulphur, with the quicksilver, which hath its being from the white body, must be espoused; from the water of brass cometh the brightness and clarity of quicksilver, which maketh white, and the same is red, for after whiteness it becometh red.

This oil therefore and quicksilver, brought into one, constitute one thing, whence the ancient and common proverb ariseth, and it is a saying of the wise: The ruddy servant taketh a white wife, and by the conception of the woman being with child, she bringeth forth a son, who surpasseth all his progenitors, that is, the Sun and the Moon. When therefore quicksilver proceedeth from the white body, it is joined to the oil, that is, sulphur.

Gloss. Quicksilver is joined with oil, that is, the solar fatness, which is the male, and that is the female.

Text. Moreover, quicksilver must by another name be designated. For those bodies white and red, which are joined or mingled, we call altogether the four bodies.

Thus then, from quicksilver in the body of the magnesia, being dissolved by the body of the white and the red, they know it to be congealed. Hermes also, in the Book of the Dukedom, which is one of the Seven, saith: Confidence consisteth in two things, unto which a third is added; and this is the same saying as before. And in another place he saith: I have seen three faces, that is, spirits, born of one father, that is, of one lineage, for of them is one kind; one of which is in fire, another in air, the third in water.

Wherefore Hamuel, the commentator of the Elder, saith: It is the threefold water of life, for it is one, in which are air, fire, and water, in which is the soul arisen, which they call gold, and call it divine water.

Text. These faces, which their father joined, the father, that is, the one genus, because they are homogeneous; therefore they are symbols: and one seeth the three natures joined, because they rejoice in one another. Then with one mouth they spake, namely, those three natures joined in water, saying: They seek the four natures of the elements, namely in the earth; for in the dead body are four, hot, moist, cold, and dry; and these are united by that water which worketh all things, namely, it quickeneth, it killeth by calcining, it dissolveth the rest, and coagulath itself with the earth.

Text. These four natures the ants, that is, the blackness in the womb of the earth of the philosophers’ brass, first brought forth into water, which is neither hot, nor moist, nor cold, nor dry, but a mean of all, incorruptible, joining fixed tinctures.

And Lucas the Philosopher: Burn them, that is, burn the silver, and burn the gold. For it is nothing else but light that is burned, because to burn is to make white, that is, by the first and second whitening. And to make red is to give life, which is the last of the work.

And he further added: The definition of this art is the liquefaction of the body, that is, the dissolving into water, and the division of the soul from the body: and again the reuniting of the soul unto its pure body. For our brass hath a soul and a body, like unto a man.

It behoveth therefore that the body be divided, and the soul separated from it, so that it be not the body that penetrateth, but the soul, that is, the tincture, in water, which is subtle and tinging the body itself, that is, it penetrateth the dead earth, and thus body and soul are in nature.

And he added a fair and obscure riddle: That the splendour of Saturn, that is, the blackness solar, which is his Spirit and tincture, when it ascendeth into the air, that is, when it is resolved into aerial vapour in its water whence it came, appeareth not at first save darksome; and then is born the offspring of the Philosophers.

Text. Mercury, that is, distilling as though dropping the good, meeteth with the solar ray, that is, the splendour of the Sun, that light may be joined to light, and whiteness come forth after the utmost blackness.

Text. And quicksilver, that is, the living water, by virtue of its fiery power, that is, solar, which is more potent than fire, quickeneth the dead body, that is, it maketh it red and perfect, that is, it fixeth it. Moreover, concerning this Stone unequal, Catis in the Turba saith: If thou wilt prove our coin unto perfection, that is, brass, see whether it be brass impalpable, that is, clean and purged from blackness, namely oil, which thou shalt behold floating idly above, and gathered, and turned into white water. If such it be found, it is apt; otherwise it tincteth not.

Rasis: The spirit hath entrance into bodies when they lie clean and purged beneath. And this is the chief root of this work.

It followeth: And know thou, if thou shalt take aught else besides our brass and our water, and water it in our water, it profiteth nothing. But if thou shalt water our brass with our water, ye shall find the truth. And he addeth: By our brass and our permanent water the Philosophers signified this Stone, which also they commanded to be cooked with gentle fire. And verily two things are our coined Stone, namely brass and water; and they are that of which the wise have said that nature rejoiceth in nature, for the nearness of nature in those two, namely the male and the female, and our water, which is of the same nature, namely the water of those two, the Sun and the Moon. Between them is the greatest affinity, which, unless it were, they would not so soon be converted into one.

And Catis in the Turba: That nothing proceedeth from man save man, nor from bird save bird. And nature is amended only by nature. From it, and not from another, is the art cultivated. Unless thou take it, and water it, thou doest not well. Join therefore the male, that is, the Sun, the son of his sister, that is, the fragrant Moon, that is, by odour or fumous evaporation, and they shall beget unto you the art. And join not unto them alien powder, nor aught else beside their own water.

And he addeth: O how precious and marvellous is the nature of this red servant, that is, of Mercury made red, for without him the regimen of the work cannot stand.

And Lasan saith: That nature is both male and female, and the Indians have called it magnesia, for therein lieth the greatest secret.

And Asfaracus: He who will attain the truth, let him take the humour of the Sun and the spirit of the Moon, for sulphur is contained by sulphur, and moisture by moisture.

And Arsilebres: Sulphur by sulphur, that is, quicksilver with brass. For all quicksilver is sulphur, but both the sulphurs are incorruptible; and moisture by moisture, that is, Mercury by the moisture of brass.

And Constans saith: Mind nothing else save this, how there are two quicksilvers, namely, the fixed in brass, and the volatile fleeing in Mercury.

And the Envious One saith: This sulphur, that is, quicksilver, is wont to flee, and is sublimed as vapour. It must be held therefore by another quicksilver of its own kind, namely of brass, and its flight restrained. For if it be not mingled with white or red sulphur of its kind, that is, with gold or silver, it will the more readily flee. Join therefore quicksilver to quicksilver of its own kind, and having done so, ye possess the greatest secret.

And Parmenides: Leave aside waters and broths, bodies and stones, but mind the coins. Take brass for the beginning, and tin for liquefaction; that is, make tablets, that is, leaves of gold; and for beginning, take it, that is, blacken it with mercury and mingle it; and take tin for liquefaction, that is, when ye see it all white, then is it liquefied, that is, turned into water. The same Parmenides addeth: Leave aside superfluous discourses, and take quicksilver, that is, compounded water, and congeal it in the body of magnesia, that is, in the earth of the divine water, and it shall become white and red, that is, gold and silver.

And it is called the Stone of Magnesia, because, according to Pythagoras, it is a thing that followeth its companion, as the magnet doth iron. For as is the affinity of the magnet with iron, so is the confirmation of water with earth. And as the soul rejoiceth with the body, so doth nature rejoice with nature like unto itself.

And Eximius saith: I tell you truly, there is no tincture of Venus in our brass. Waste not therefore your money in vain, bringing sorrow to your hearts and souls.

And Hermes saith: That Azoth, that is, quicksilver, and the fire of putrefaction, the fire of the wise, do wash and cleanse Laton, that is, brass, and utterly take away its darkness from it. Which if thou rightly orderest the fire, Azoth and fire in this disposition suffice thee.

Wherefore the Destroyer saith: Whiten Laton, that is, brass, which cannot be whitened save it be dissolved in Azoth; and rend your books lest your hearts be rent.

And Dantinus saith: Though Laton at the first be red, yet is it unprofitable; but if after redness it be changed into white, it availeth nothing. And Hermes: First is blackness, and afterwards with salt and anaton, that is, fire and mercury, followeth whiteness. And first it was red, and at last white. The superadded blackness shall altogether be taken away, and then it is turned into red, most bright and beautiful.

And Marion said: When our Laton, that is, our brass, is burned with Acidbrie, that is, with our moist, white, incombustible sulphur, and the moisture of Azoth is poured upon it, so that its fervour, that is, its hot fatness, be taken away, then all darkness and blackness shall be removed from it. For moisture in the fire bringeth forth blackness, which moisture being digested, whiteness followeth; so it is in this matter. And when it is converted into most pure gold, that is, into golden colour in effect, not in appearance—for gold is viscous and white in sight—therefore not in vain have I added testimonies concerning the ore of the art from divers places.

For Morienus saith: I tell thee, in species and in weight expend thou nothing, and chiefly in the making of gold. For whoso in this magistery shall seek aught else than this Stone, is like a man striving to ascend by ladders and steps, who, when he cannot, falleth prone upon his face to the earth.

And afterwards he saith: That in this Stone are the four elements, and it is likened unto the world and the composition of the world. Nor in the world is any other Stone found that may be likened unto it in effect or in nature. Whosoever therefore shall seek another stone beside this in the magistery, all his works shall be in vain.

Hamuel: Already the wise have shown unto thee plainly the manner by the philosophy of vain things, whereby thou hast gained much and redeemed thy money, that it be not spent in vain. And this is a great profit if thou understandest it.

Therefore, that this chapter may be more fully manifest, the figures of the ores and their compositions, with the distinction of the double work, which the Elder in his house in his image described, a fairer knowledge, though delivered more obscurely, I will briefly expound.

The Elder saith: I entered into a certain subterranean house, which is the house of treasures. And I beheld set in order nine images of eagles, having their wings outstretched as though they would fly, their feet extended and opened; and in the foot of one eagle was the likeness of a great bow, such as is oftentimes bent for shooting arrows.

And on the right and left sides of the house there were images of men, as perfect as might be, standing clothed in divers kinds and colours, their hands stretched toward the inner chamber, inclining toward a certain statue within the house. And in the innermost part of the chamber there was the image of a wise man, who held in his hands upon his knees a tablet of marble, of the length of one arm and the breadth of one palm. And the fingers of his hands were bent over it, and his forefingers, as if he signified one should look upon it, even as in an open book it seemed to every beholder. And that tablet had columns like unto a book, and was divided down the midst; and on the side where the Wise Man sat were images of divers things and barbarous letters.

And in the first half of the tablet were five in the lower part thereof. The first sphere of two birds, their breasts bowed toward one another: one of them with wings cut off, namely the male; the other above it, winged, namely the female. And each held with its beak the tail of the other, as though flying one would fain fly with the other, and the other would hold back the flyer. These two birds were of one kind, in one sphere.

Then another sphere, the third: the full Moon. Above, in the first tablet, were two beside the head of the flyer: the image of the crescent Moon; and on the other side the Moon in a sphere. In the other half of the said tablet, the second, there were likewise three above and two beneath. Above, the Sun with two rays, which is the double Sun, and the image of two in one; and on the other side, the image of the Sun with one ray, which is the simple Sun, as an image of glass in wine. And the rays descended compassing a black earth, parted below into three. The third part thereof had the crescent Moon, the inner part white without blackness, and a black sphere encircled it. And these are two, namely the earth of two natures, the black sphere and the Moon which it compassed. And above were three, namely the Sun with two rays, and the Sun simple with one ray. And these are in all ten, according to the number of the nine eagles and the black earth.*

Gloss. This house of treasures is the vessel of the art, hanging in the clay of the dunghill, of which more shall be said at large. The nine eagles are the nine parts of vinegar, or of our sea, for as the feathers of the eagle receive gold when it is gilded, so no other thing can dissolve the Sun, save our eagle; nor is there any other water but this golden. Whereof Marion saith: Nothing can take from Laton his darkness or his odour, save Azoth, which is as it were his regimen; first, when it is boiled, for it tincteth him and maketh him white; and again Laton ruleth Azoth, for he maketh him red. Another Philosopher also saith: And Azoth cannot substantially take away from Laton his colour, nor change it, save only as to appearance; but Laton from Azoth taketh away his whiteness substantially, for ashes have a marvellous virtue that appeareth above all colours. Laton indeed ruleth Azoth, and maketh him red with the nine eagles, that is, nine parts of water, the volatile tincture of our brass; and subliming it in its vessel it is altogether whitened.

Wherefore Rasis: The substance of all things is equal to the tenth part, but if thou wouldst signify the whole, nine parts must needs be made of the substance of water.

And Moses in the Turba: Join first nine parts of vinegar; for these are the eagles that have their bows outstretched, mortifying the body and drawing forth its soul, which is the tincture of brass.

Parmenides: This Red Sea turneth gold into red fire, for nature rejoiceth with nature. Boil therefore in the humour, until the hidden nature appear, that is, until it be deprived of the blackness that was Ethel from Ethel, that is, from silver of Rosin. If ye dissolve, that is, if ye resolve into our water, the white body, that is, our brass, there shall be drawn forth from it flowers, that is, its tincture.

And Aristaeus in the Turba: Take the body which the Master bade, making thereof thin plates; then put them into the water of our sea, which, when they are covered, is called permanent water. Boil it with gentle fire until the body be dissolved and made water; and cast in Ethel, that is, quicksilver; and roast them together with gentle fire until it become a broth marked with solar fatness, and be converted into its own Ethel, namely from which it was, and the nature is composed, until it become a good coin, that is, blackness, which we call the flower of the Sun. Boil it also until it be deprived of blackness and whiteness appear; and this is burnt brass and the flower of gold.

Pythagoras in the Turba saith: There is a most sharp vinegar which maketh pure gold to be spirit; which having, neither whiteness, nor blackness, nor rust abideth. And when that vinegar is mingled with the body, it turneth it into spirit, and tincteth it with a spiritual tincture which never can be blotted out.

And the son of Azir: This vinegar burneth the body and turneth it into ashes, and also maketh it white; and if it be boiled until it be well deprived of blackness, it becometh a Stone and a most white coin.

Afterwards he addeth: Now by this disposition is shown unto you a nature stronger than all natures, more powerful and more noble, which I know to be the pure vinegar, by the mercy of God alone. And the more I read books, the more I perceived. But men, as perfect as they might be, clothed in divers kinds and colours, are the Philosophers and Prophets, the servants of God, who beckon to the reading and understanding of the wisdom of the Most High, that they may perceive that to the servant of God his treasure shall never fail. But the barbarous letters and the infinite kinds are the riddles and dark sophisms of the wise, that they might hide them from the wicked. Wherefore in the Turba: Though they have infinite names, yet by one name are they named, wherein is no deceit nor diversity. And where it profiteth not, it is magnified with great names; and where it profiteth, there it is hidden. For it is a stone and not a stone; and because it is spirit, soul, and body, it is white volatile, white volatile hollow, as touching the porosity of the earth. And because it drinketh up all its earth, it is salt, hairless, which no one over-subtilised may touch without great offence. If thou makest it fly, it flieth; and if thou sayest it is water, thou sayest true; and if thou sayest it is not water, thou sayest false.

Be not therefore deceived by the multitude of names, but hold it certain, that each thing is that which it is, to which no alien thing is joined. Seek therefore its companion, that is, brass, and join nothing else thereto. And suffer men to multiply names; for if they did not multiply them, children would deride our wisdom. All these things are written in the Turba, at the end, concerning the riddles of the wise.

Two birds are homogeneous, that is, of one nature, and they are the Stone of the Wise. The male is without wings, that is, he cannot fly, because fire of itself cannot corrupt him, nor can he exhale in the fire; nor can any salts or spirits or alums (save our eagle so called). But the winged bird is the female, which with corrupting bodies is consumed. Hence they said: Set the female upon the male, and the male ascendeth upon the female; for by the help of the female and of her water he flieth, and becometh a moist spirit, and quicksilver is drawn forth by men—that is, by reason and great understanding.

Whence Theophilus: And whatsoever the envious have obscurely related in their books, they meant to signify quicksilver— which some have called the water of sulphur, others white lead, others brass—sometimes it is named the compounded coin. And they joined the male with the female in his proper humour, because without male and female no offspring is generated.

Morienus described five parts or orders of the Stone: first, the coitus; second, conception; third, impregnation; fourth, birth; fifth, nourishment. For if there be not coitus, there will not be conception; and if there be not conception, there will not be impregnation; and if there be not impregnation, there will not be birth. This is the ordering of the operation, for it is likened to the creation of man. Whence Morienus said afore: O good king, I confess the truth unto thee, that this standeth most of all by divine nod in its creation. For every creation is of God, and cannot subsist without this water, to wit, the humour or water.

And afterwards he addeth: Why should I rehearse many things? For this thing is drawn from a thing. Its ore hath never existed with thee; yet they found it; and, to confess more truly, they take it from the thing itself, and thou hast demanded it of no ore. Understand, as to the creation of man, of male and female; and of lust, as to the moist.

For if there were not moisture in the womb, as Bonellus saith in the Turba, the seed would not be preserved until it bring forth the foetus.

And the Constant One calleth his Stone a watery moist thing, for a sophism. And know, my son, that this Stone, from which this secret is drawn, God hath not set to be bought with a price; for it is found cast forth in the ways, that it may be had of poor and rich, that by reason and knowledge a man may lightly come unto it. And the moist is everywhere; and our Stone is moist with a watery and metallic moisture; whence they said it is both the vilest and the most precious thing in the world.

For the common humour, of which all things are generated, is beyond price. Hamuel expoundeth this vilest, saying: The most precious thing in the world, of garments, is silk—and it is of worms; and honey, wherein is the health of man, is of bees; and pearls are drawn from shells. And man, who is more worthy than aught that is in the world, is of seed. But the brass of the art, and the ore, only the opinion of men maketh precious, as is nobly said in the book Consolation of Philosophy.

For the beauty which they have is not theirs but of the light; for every colour is light terminated by an opaque in a perspicuous body. For gold and silver and gems of their nature will to lie hidden in the mire and in the dark earth. Whence Morienus would signify this, saying: If thou findest that which thou seekest in the dunghill, take it; but if thou findest it not in the dunghill, withdraw thy hand from the purse. And likewise Gratianus: And if in the dung thou findest that which pleaseth or profiteth thee, nevertheless take it—signifying that thou must take of the fresh ore which hath not been in the work. And what Morienus addeth: For every thing that is bought at a great price, in the craft of this work, is found lying and unprofitable, signifieth the forbidding of vain things—as pearls, quicksilver, sulphur, arsenic, sal ammoniac—which flee the fire. How then shall good be expected from that which is not permanent? For a tincture drawn from a bodily and combustible root is annulled like its root. For things are not changed, as they go out from their root, in minerals; nor is it seen so in the seeds of vegetables and the seeds of animals: as from an egg a chick ariseth by divers transmutations from that whence it hath its root; and likewise from seed a man is made, nothing else supervening save the menstrual blood, from which the seed is made—of blood equal and like unto itself—by which thereafter it is nourished.

But the excretion of dung and urine, blood, hair, eggs, and the like, have no neighbourhood with metallic things, so that of their root gold and silver could be made, as certain ignorant ones suppose: for naught goeth forth from man save man; nor from a like thing save a like unto itself.

Therefore gold and silver go not forth save from a like species. Whence the Elder, son of Hamuel: Every animal is not generated of itself, save with that which is of itself, with its own species, which is homogeneous unto it. Likewise Adam and Eve and all the race of men. Therefore every thing agreeth with its like, and is near according to species. Begin in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, and know its nature: for it is of the root of its matter; that which is in the same and of the same; nor doth any other enter upon it which is not also of it; and it is its root. Likewise Mercury is of it; and this is that from which it is extracted; and it is in it and of it.

For the Stone of the Philosophers is water congealed, as in gold and in silver; and it withstandeth the fire and is resolved into its own water, of which it is composed, of its own kind. Whence Hermes: Naught befitteth a thing save that which is nearest unto it by its nature; and it will beget an offspring like unto it. And straightway it is subjoined: Moisture is gold, under the dominion of the Moon; and fatness is under the dominion of the Sun. Whence these two—Sun and Moon—are one, and the curd, and the seed. And King Aros saith: Water is not glued save with the like of its sulphur; nor is there found in a thing aught like unto itself, save that which is of it. And Calid, son of Iesid: Neither those past nor those present can tinct gold, save with gold; and the rest thou shalt find in the Senior. And these things said concerning the two birds and the eagles may suffice.

It followeth: Why did he set many Suns and Moons? It is answered: Because the spirit and the soul go not forth together in one act, but little by little, part after part, successively. These are clearly declared in the Senior; but I will expound that which he omitted. Two full Moons and halves are five, to be reckoned from the lesser: to wit, the half Moon, and four half Moons are in two full [Moons]; and the two Suns are all seven. Hence it is that he saith afterwards: Seven are the orders of the weight; five of them are without obscurity, namely the Moons; the beauty of the two shining ones, that is, of the two parts of the Sun. And because there is nought but the image of the Sun and Moon upon the tablet, and number—the weight followeth the number of the figures upon it. And he presently subjoined: Know that of one root there be not less than three and the third half-part—that is, the weight that is set with it (to wit, with the Sun) unto that third, namely nine. For, as Hermes saith, the Sun and Moon are the roots of this art. And Rasis biddeth receive three parts of fire and seven of earth, and part answereth to part, as he saith, by equality of proportion. And, according to the opinion of Obede, Rasis: of Light four parts, and of Air one part, and of Fire one part. In the Book of the Three Words four weights are set: first, of earth eleven parts, and of fire one part; and add unto them of unguent, and set to dissolve until they be made together. And this dissolution is taken from that colour. Some say three parts of earth and one of fire; the regimen is one and the same, and either is right, yet the first speaketh better.

And Zenoa in the Turba saith: One part of the sincere body, that is, of the Sun, and three of the other brass; then mingle with vinegar, and straightway cook until it be earth.

And Dardaris in the Turba saith: And four coins dye the vulgar; but they dye brass, that is, Mercury; and brass being dyed, they dye the coins of the vulgar. And he saith that quicksilver is of four bodies, which are souls hidden in four bodies. Others say, Not so; but there are seven parts of earth and one of fire—and this also is good, yet the first is better.

Some do say, Not so, but that there be eleven parts of earth and one of fire; and the regimen is the same, yet the first is better. And he addeth: Work therefore as thou wilt, for the regimen is the same, and the space of time also the same. And, as one saith in the Book of Lights: They will three parts of earth and one of fire, which yet pleaseth not Rasis. For he saith: The inequality of price ought not to be changed.

Note: The leaves with two parts of ointment must be amalgamated by wind and fire, and afterwards the whole ointment cooled with its true weight, so that it be nine parts of neighbours and one part of brass. And in the Turba, Pandulphus: Behold, in the egg are four things—earth, water, air, and fire—and in the midst a red point of the Sun, which is the chick.

And Morienus saith: That the first proposition is almost nothing. And a certain one experienced in this art said: A little of the Sun, as a drachm, that it be the seed of fire. And the Constant One, searching all, saith: I found two substances, namely the agent and the patient; and lo, the agent is now everywhere, but the patient in many things. Whence it is known that in this work, of one taken two are made, namely male and female. Moreover, the male is everywhere singular, but the female in many.

And note: the weight of the art is double. One is the common, wherein is no diversity, namely nine and a tenth part; the other is the singular or plural, and it is double: the first of the first work, and that is in the first composition of brass, and it differeth from the second diversely. Note of the weight of imbibition, how much, namely, the blood can imbibe of the parts, which nature knoweth better than the artificer. For nature doth the imbibition, not hand nor handling, but fire and Azoth, as the Constant One said.

Now there is another weight, spiritual, of the second work; and that likewise is diverse according to divers masters. Athomus in the Turba willeth the third part of fire and two of earth to be mingled. For he saith: If there be twenty-four ounces, quench the heat with a third part, that is, eight ounces of vinegar.

And Bonellus in the Turba warneth, saying: Beware lest ye multiply the humour, nor set it dry, but make it as a mass firm; knowing that if ye multiply the mass of water, it will not contain it, nor will it burn well in the furnace, that is, it will not dry well; nor if ye dry it too much, will they be joined or cooked.

And Arsuberes likewise in the Turba: Join it with snow-water, as with a man it may be thought sufficient, and boil until the rust be consumed.

But Morienus willeth a fourth part of fire and three of earth. For he saith: When thou shalt have led the foul body, afterwards put of the ferment, that is, of aqua vitae, the fourth part thereof. For the ferment of gold is gold, as the ferment of bread is bread. And when thou shalt have put it, set it in the Sun to cook, until these two be reduced into one.

And Hermes, to whom none was like, teacheth to add a fourth part, and that not at once, but from fourth to fourth, that is, in four days, each day a fourth. And grind in a mortar until it become like fatness or ointment, and afterwards roast unto dryness, and again grind to moisture in many days. And this nine times dissolve and coagulate; for in every solution and coagulation its effect is increased.

Rasis in the Book of Lights teacheth to add an equal part of water unto the earth, as in his work appeareth; yet Helmer’s method is better than theirs.

And know: the Philosophers oftentimes set the end before the beginning in their treatises, and the beginning in the end, interchanging. Whence sometimes they depressed the first work and spake of the second; sometimes they recalled the first work and left the second; sometimes with roots of knowledge, sometimes without ores.

Wherefore Hermes, in the Book of Roots, which is the second of the seven, saith: The wisdom of the author is greater than his book. For he may take away the beginning or the end, with the root or without the root, as the first inventor. And in the fifth of the seven, after he had spoken enough concerning the conjunction of water and earth, and of the weight of the second work, namely of the fourth part and of the fifth part, and of another set two ways to be swallowed, then he speaketh of the first weight at the end, saying: That according to the sentence of the heavens, and according to the sentence of particulars, and according to the sentence of good materials, it is a secret. And I will say unto thee but singly. And it is this: one part fire and three of earth. And now by God be blessed, for natures are four and no more.

Whence their weights are multiplied: either by the four natures of the elements; or by the four natures and the second water; or by the plurality of things, to wit, three, which is the perfect number; or by the seven planets; or by the twelve signs whereby the work is ruled. They set their weights accordingly: the first set a fourth part of the Sun, the second a fifth, the third a third or a little more, the fourth a seventh, as Rasis put seven parts of earth and three of fire; the fifth a twelfth. And by divers reasons they set divers weights. And sometimes, speaking of one work, they set the weights of another. Whence the Elder: And they perchance spake a word in one sense, and under it is another.

Furthermore, the first five: namely two of the upper— the waxing Moon and the full Moon— and three others subtle, namely the two birds and the full Moon, signify the first work, which is the extraction of tinctures from the body, until nothing remain in the body that ascendeth not with the moist spirit, whereby the body is modified and turned into clear water. Yet first appeareth blackness, from the dominion of the moist in the hot, which lasteth so long until the moisture be consumed; then the water is whitened. And of this water Morienus saith: That with it thou shalt do nothing, save it be fermentative itself.

And the Elder saith: Before thou descendest, thou hast made these three parts of water, namely water, air, and fire, being in the water above their white and foliated earth. That is, in the second work, the first in the first work is wholly dissolved, namely the moist body, and becometh earth, that is, the Stone. Whence their first preparation is necessary, as is the custom; and this is the putrefaction of the body, each beastly subtle, one hundred and fifty days; and some say one hundred and twenty natural days; and perchance whiteness first shall appear in one hundred and seventy days. But this is not approved among the philosophers, because it signifieth the intent of the fire.

And therefore the first in humour is with him better than the second or the third, because it signifieth the temperance of the fire, until whiteness be given and redness returned. Note, albeit these refer back to the first dissolution of things, yet the Elder meaneth the second whiteness, which in one hundred and fifty days is resolved, with certain colours of days; or in twenty-one days it is resolved into water; or in one hundred and fifty days is resolved the second whiteness, which is the first work and the whole coagulation of the whole. This is more true and proved.

Of this putrefaction Pandulphus in the Turba: Most hidden, most honourable, this is the white magnesia, which being mixed and ground in wine, take not unless it be clean and pure; and set it in its vessel, and pray unto God that He make thee to see the right Stone; and cook it gently; and when thou hast drawn it forth, see if it be black; and if so, thou hast ruled well. But if not, rule it white, which is the great secret, until it be covered with blackness; and afterwards blackness cometh, which lasteth forty days only, and it is whitened and coagulated.

And this water is the flower of brass, the Indian gold, the water of saffron, and fixed alum. And as Asuarus in the Turba, by authority of Hermes, saith: Hermes commanded that a part of the coins be taken, that is, moist white, and of the brass of the philosophers a part, and mingle it with the coins, and set it in a vessel well shut, and boil it seven days of one name; then shall brass be turned into coins, that is, into moist white, and again coagulated seven days, and let not the decoction cease. Afterwards the vessel shall appear, and blackness shall be found. Again repeat the decoction, until the blackness be consumed, which being consumed, a most noble whiteness shall appear; and so it shall take the humour of the Sun and the spirit of the Moon. And this is the first work, which no other goeth before.

Now the two homogeneous birds are male and female, but the number of two set into one in the figures, namely seven. But the full Moon sudden, signifieth the humour of the Sun and the spirit of the Moon, of the moist Stone of the philosophers, drawn in its water.

Above is the crescent Moon likewise; for little by little, and not at once, but part after part, the tincture ascendeth, until all the humour, congealed in brass, be turned into a moist spirit of its kind. This is signified by the second full Moon, which is Abarahanas perfect, and of that divine water, which is the Stone of the Philosophers, is the whole book of the Elder.

The second half of the figures signifieth likewise the second work, that is, of congelation, namely of the parts of their water, that is, of the colours of water in the white and clean earth, that is, of the fixation thereof therein. The Sun with two rays is the image of the divine water, in which are three, namely fire, air, and water; and it is water compounded of two natures, male and female. And yet it is threefold water, because of the third thing added to the two. And this water is not all imbibed at once, that is, ground, but singly, with divers rays it is imbibed, ground, coagulated, and incinerated. The Sun with one ray is, that the threefold water is one natural and homogeneous in one water. And albeit the works be two, white and red, yet is it one work, beginning in the same and ending in the same, and not otherwise; and it is the figure of one in one.

The Earth is the lower body of two bodies, unto which a third of its kind is mingled; which is first coagulated, like unto a mirror or a bared sword; and afterwards by greater heat is incinerated; and again ground with the moist spirit until it no more appeareth, but is mingled with it, and becometh as ointment; and again is coagulated; then incinerated. And thus this first must be brought again to its end, until it be fully whitened with fixed whiteness. And this is the second and third of the art, of which Morienus saith: O king, if thou hadst sold thy kingdom, thou wouldst not recompense this work.

Then again it is imbibed, until it be mingled, and congealed, and incinerated. For in the Turba Pandulphus saith: Know ye, as oft as ye unite ashes, so oft must ye dry and moisten it, until its colour be turned into that which is sought, and the whole be coagulated. And in the imbibition it putteth forth infinite colours, until the perfect and last, crimson and fixed, be brought forth by continual fire, without handling of the hands.

Whence the Philosopher Mundus: Afterwards in forty days finish, until the spirit penetrate the body. For this is the regimen whereby spirits are incorporated, and bodies turned into spirits. And I warn you, let not the compound fume; which done, ye have the greatest secret, which the Philosophers have hidden in their books.

The Earth which the black sphere compassed is the second blackness, which cometh by the moisture of the water cast upon the earth. But that it is divided by its third, that is, by three thirds, signifieth the three saltations, or three earths: namely the earth of pearls, and the earth of leaves, and the earth of gold. The earth of pearls is the first earth, from which tinctures are drawn in its water, whence proceedeth the pearl. The second is the earth of leaves, that is, of colours: for it bringeth forth variable colours, until it be perfectly whitened. And when it is perfectly whitened, that is the third.

Or it may be said, the first is the earth of leaves, because the leaves of brass being changed pass into water and earth; the second the earth of pearls, when it is fully whitened; and the third earth is the solar tincture, and itself the earth after denigration. The second whitened is called the gold of the Philosophers. And the water is their gold, for it is the matter of gold which begetteth gold, according to the Elders. And those three earths are one nature of one sphere and one kind.

And in like manner it is to be understood of the three saltations, and saltings, that is, imbibitions with the three smallest earths. The first third is congealed and incinerated, and becometh male; and there are two males, of the Sun and of Mercury, and one female of Lunar nature. Then by the rest of the water, which are six parts of colour, is made another female; and there shall be two males and two females.

The second third is the saltation, which is nothing else but this: calcine, dissolve, distil, coagulate, and incinerate, and again calcine, until the whole be coagulated. And by figure is signified the last third and the end of the work. Of these three earths the Turba, in the chapter of enigmas, speaketh throughout; dividing its work into three: first, into the dead body, and the extraction of the soul from the body, which is the first work; second, into the whitening of the body, and its cleansing by its own water, imbibing and roasting, until it be whitened like unto snow or white salt; third, into the clean soul joined to the clean and white body.

Wherefore the first enigma of the Turba: Take a man, beat him upon a stone or plate, dragging until his body die, and his spirit be drawn forth: this is the first. Then of the second it saith: thereafter the body shall live again, until it be spiritual, and its thickness perish. And be thou sure, when it hath lost its grossness, it shall be made spiritual. Of the third it followeth straightway: Restore to it afterwards its soul, that is, the lively and vivid colour; then set it in the bath for forty days, as the seed abideth in the womb: and this is the beginning of our regeneration. And thus ariseth creation, and the proposition is fulfilled.

Lo, he setteth three earths: the dead earth; the white earth, which is the inner Moon of whiteness; and in the whiteness, redness—that is, the living earth, which is the third earth.

Whence Florinus in the Turba: When ye shall see that whiteness excelling, be ye certain that redness is hidden therein. Then must ye draw it forth, and so long boil it, until it be wholly made red.

And that which is said, “for forty days,” signifieth one name. Athomus likewise saith, “for forty-two days,” and addeth the measure: even as seed tarrieth in the womb, which is forty weeks. And because this may be done sooner or later, Athomus addeth, that this second work, from the tenth day of the month September, which is the first month among the Egyptians by reason of fruitfulness, unto the tenth of Libra, is perfected—that is, within the year is its perfection; for by diversity of fire it may be finished sooner or later.

And after the soul is joined unto the body, the fire must not go out, namely by three terms and three degrees of fire, and the alteration must be gradative, until in the third degree it be finished, as Gratianus saith. Concerning the determinations and degrees of fire, consult the Book of the Three Words, where I have expounded it.

Note concerning the house of treasures, of which the author spake in the first: The Constant One speaketh thus: Therefore, my sons, I will show you the place of this Stone. Let not the unskilled presume to read it, nor despair of coming unto knowledge. For this is in a place which is in very truth the place of the four elements; and there are four gates. If thou wouldst know them, I say: first, they are four stations, four corners, four bounds, and four walls. These four I will expound by four keys at the end of this poem.

It followeth: This house is a treasury, in which are treasured all sublime things of sciences and wisdoms, or of the most glorious matters that may be had. And this house of treasures is shut with four gates, which are opened with four keys. To each gate is one key. None can enter into this house, nor draw aught from it, nor know the secret that is therein shut, unless first he know the key and bear it with him, or at least be of the household of the house.

Know then, my son, and heed well, that he who knoweth one key and knoweth not the rest, shall open the gate of the house with his key, yet shall not behold the things that are in the house; for the house hath a surface tending inward unto the sight. Therefore must each gate be opened with its several key, that the whole house may be filled with light. Then let whoso will enter and take of the treasure. Know, my son, that unto thee the treasures are not hidden, but are kept in that house before thine eyes, when thou enterest into the house.

Yet will I show or bestow upon thee one key, which by its signs thou shalt find; by which, if thou hast reason, thou shalt find the other three from it. And this one key is the access of water through the neck of the vessel, at whose head is the likeness of a human creature; and it is the basilisk of wisdom, without a horn, which draweth forth water with the horn of the stag, and the bud of the chief water, and the brightness of the most fair river, whose stones are most renowned—precious stones, gems, and corals.

From the vapour of their fatness is made one key. And if thou wouldst have perfection, thou must draw forth the other three, and know the glory. Of the four bounds, the first key is the extraction of humour and fatness, that is, of water and oil. And the humour is of the Moon, and the fatness of the Sun. Whose signs are these: an exceeding blackness; which, when consumed, the soul is purified in water by distillation.

Vietimerus saith: Thou shalt wait for the water to be sublimed of vapour. For when thou shalt see nature make water of the heat of fire, and the whole body of magnesia as melted into water, then are all the vapours made, and by right the vapour draweth and holdeth its mate, for the fixed holdeth the volatile. For natures cast themselves unto natures.

And Rasis in the Book of Lights: When thou makest the inhumation, until it be turned into soft water, then thou shalt have thy desire: and this is after the first whiteness.

The second key is the attenuation of the earthy body; for there abideth in it rigidity and pliancy and foulness, which cannot be stripped away save by laborious and subtle wit, as is said in the Turba. For the body cannot be made thin so long as pliancy and rigidity and hardness remain in it. Let the body therefore be taken, as the Turba saith, and washed; and at a slow and tepid heat of the fire let it be rubbed; and, even as they who with ashes and water of the stronger lime make things white, let it be very white. Then let it for one night be left in a moist place; afterwards, being washed with sea-water, let it be sprinkled little by little until it be most fully whitened, until from all defilement it be cleansed and be seen most white. But let this whiteness not be without great blackness first, in whose belly is this whiteness of our most white salt; and this is the second key.

The third key is the imbibition of all the water, that is, of the remaining humidity— which now hath the name of oil— with long grinding; for roasting and congelation, incineration and waxing, must be made with the same oil, until the whole water be brought together into one.

The fourth key is fixation in three terms and three degrees of fire, until it be fixed and tinging.

And the Constant One addeth in another chapter: Then, after the coagulation, make it fly, for certain months— that is, for forty days of one name— in warm dung, that is, in the moist fire of the fleece, until the water grow red and thicken and become equal. And I understand that the Constant One will have three parts of earth and one of fire; for he saith: From the vapour of their fatness is one key; and fatness is fixed under the dominion of the Sun. And if thou seekest perfection, thou must draw forth the other three parts of earth. But the first gloss is the better, and this deceiveth not.

And note that all philosophers expert had one vessel; the inexpert, two— at least one for the register wherein they perceived the remainder. Whence Gratianus saith, And note, if all things be prepared together by the experienced, it is good; yet greater experience is for searchers when the single things are prepared singly and examined, one by the remainder. For thou canst not otherwise prepare singly; for one water sufficeth not without the other— that is, the Lunar without the Solar— nor is aught begotten of one only, but of male and female together. And by God, in expounding all these things, for a long time I consulted those men, a hundred times by reading readings; and I had this not save by inspiration from God. And in few words we have shunned much talk, and have the favour and blessing of the Elder.

Then will I briefly set forth the doctrine of the Constant One. Take the whiteness and the blackness— which are the first and second keys of the work— and leave them while they are cooked, that is, fermented, that is, corrupted, in the alembic and in its vessel; and it ascendeth— that is, is sublimed into vapour— in its own moisture. Cast away the dregs, that is, the blackness which is Ethel; blot it out and purge the water; stretch the water, that is, wash the water.

Gloss. Hermes tincteth according to the quantity of clearness; wherefore stretch the water, that is, distil it by subliming, until it be clear, and all the moisture of the mass be drawn forth clear and white; make the earth clean from grossness and rigidity, or make it a subtle ash deprived of blackness. Close the vessel firmly— with gypsum or wax and white of egg— for there are winds therein; which if they be not held, the whole work would perish, as thou seest in Morienus to King Kalid in the Dialogue: truths most true. For it would chill the matter in the vessel and quench the fire. Truly smoke— that is, let not the matter smoke out of the vessel; neither let there be the smoky signs of wood-coals, but the subtle fire of beasts, well hooded. Bring the fire nearer— that is, let the massing of the earth with the water be stronger by setting near; keep the putrefaction. Gratianus: And let each thing calcined be dissolved in its manner, that it may putrefy. And Morienus in the Dialogue of the Wise Author: All the strength of this magistery is not save after putrefaction. He saith: If it be not putrid, it returneth to nothing. And he subjoineth, that after putrefaction the Most High God shall bring forward the state— composition, cooling, and heating; truly, that is, the excess of heat and of cold— persevere in temperance, that is, in the mean; keep away from extreme heats, not excessive. And all work is marred beyond measure, that is, by excess and over-abundance; so that the mass be neither too dry nor too moist.

Whence Bonellus in the Turba: Know that if thou multiply the water of the mass, the fire containeth it not, nor will it burn well in the furnace; and if thou dry it overmuch, it will neither be joined nor cooked. Hasten not. Whence Rasis in the Book of Lights: When water is mingled with ashes, it whiteneth it within; wait therefore for the whiteness. In this business, if the difficulty of working, or weariness, or fatigue, affect the workman with negligence, the very waiting bereaveth him of joy, choketh hope, destroyeth esteem.

It followeth: Be patient in cooking and in putrefying; grudge not the time. Albeit it be long, yet in the Elder’s sight it is nearer than every other work. And talents ever prepared never prosper. It followeth: And near, truly, as the Elder said, this work is not accomplished save in many days; nor is it needful that the glass be latticed. As Hermes saith: It sufficeth a man for a thousand thousand years; and though every day thou shouldst feed two thousand men, thou wouldst not consume it; for it tincteth unto infinity, and so greatly that it cannot be comprehended by understanding. And in the fifth book of the seven he saith: Thou shalt not know its effect until thou hast wrought and completed; and all this thou knowest already, how infinite it is, etc.

It followeth: And the “animals,” that is, the colours which are through the living water in the earth, foul not— that is, defile not— with dregs, that is, with powders or blackness. For, as Rasis saith in the Book of Lights: Let there never be black at the end; for if aught black remain, the medicine is imperfect. And the Elder saith: If blackness remain in it after its reddening, thou hast sinned in its preparation and hast corrupted whatsoever thou hast wrought; and remember, for grief of the sin and the loss, for these are incomparable riches. The living colours are white, citron, and ruddy; for, as is said in the Turba: Burning maketh white and maketh red; and therefore he said “animals,” because the soul of certain things colour eth and quickeneth the body.

Yet some books have: And be not loath to beget the animals, that is, to bring them forth; for the offspring of the Stone is a colour ever lively and abiding for ever. Some books have animals: foul not, that is, open not— let the vessel be shut. But in the register those animals, that is, the colours, thou mayest assay.

It followeth: Be not weary in what thou doest; redden until all the water be coagulated— yea, until it be coagulated— and flee not the fire; that is, let it be fixed. This is the proof above all proofs: if, being firm upon an iron plate, it emit not, nor flow like wax, and adhere firmly to the metal.

It followeth: For the water knoweth the battle of the fire, and the length of cooking and putrefying and thickening. For every work is double to itself; and the artificer followeth their nature until it come to its order by fire and by cooking.

It followeth: Then— that is, after the coagulation— in warm dung, that is, in the fire of the wise, surround the vessel and Laton for certain months, that is, nine, even as seed abideth in the womb, as it is said in the enigmas of the Turba: Make it abide or fly, that is, ascend. For it ascendeth and descendeth in the tree of the Sun, until it become Quelles, that is, the Elixir. That which he saith “for certain months,” Mundus in the Turba calleth forty days, and addeth what they be, even as seed abideth in the womb, that is, nine months or thereabout.

It followeth: Know also that no Quelles maketh red save that which is made of scarabs— that is, of the red pigment, which is auripigment. It followeth: Let no water be Quelles, save that which is made of scarabs, our water.

For this water alone is the water of the infinite treasure. And thou sayest rightly: Let no water be Elixir, save this water of the red oil, which is the singular water, and none other; for no other is wholly known. Whence Rasis: All other stones, our Stone excepted, bring forth a liquid water; for from what elements our nature is constituted, it is known; and that is of the most temperate complexion, and of the strongest composition. But the water of other stones is simple liquid, of feeble composition.

The Elder: And if any should labour to find another medicine for this operation, he could not. And elsewhere he saith: After God, thou hast no other medicine. For this verily is the art of the wise, which driveth away poverty. And he subjoineth: Neither the ancients nor the present can tinge gold, save with gold. And what is not gold—namely, their Stone—from it proceedeth gold.

And blessed Assiduus saith: When we speak of the substance, we name not gold until it be wrought gold; for it is not called gold, but heavenly and glorious water—namely, our brass, and our silver, and our silk. All speeches beyond are vain; for it is one and the same, namely, Wisdom, which God hath offered unto whom He would.

And Assiduus subjoineth: Whence cometh the word? Go unto the fountain, O thirsty one, and arriving in the land of the black or dusky, for it behoveth that the earth be blackened in the first work, as also in the second and in the nine. Nor is there need of more than nine parts of vinegar, according to the Elder and Moses in the Turba. And Hamuel setteth nine eagles.

It followeth: Even so, strangle them, that is, shut them in a vessel well sealed; and take their blood, that is, their redness, their fatness, which is their poison, slaying, that is, the icor of all imperfect bodies, whose leprosy it slayeth, and which reduceth the Mercury of competition into perfect gold. For it converteth not aught, save that which is of its nature, and becometh unto it.

It followeth: That which ascendeth to the heights, and straightway floweth to the receptacle: boil it until it be red, that is, until all the tincture be drawn forth, which is after the utter blackness, whereof whitening is the sequel. And straightway he addeth: I will signify to thee this Stone. Unless this vapour ascend, thou hast nought of it, for itself is the work, and without it nothing. And as the soul unto the body, so is it, which is the Quelles. Say not then that of envy I have written, and have not named the water, albeit I have named it. Look, and believe me, that this Stone is not a Stone.

Never hast thou heard any Philosopher say that this Stone is the water of the living fountain. And Rasis in the Book of Lights: Our Stone, in which is all our effect and grace, is of a brazen vision, indeed of water, of the nature of fire, burning in colour, entire in the property of natures; neither hard nor moist; a substance also that melteth; and apt for the use of many medicines, and vile, so that in all its showing it taketh the form of water.

Then follow the further precepts of Assiduus, saying: In this book is the perfection of the letters of vellum, and the most perfect and certain work in the midst of its kind: which Sun is in the midst of the planets, that is, of the metals, of middle and temperate complexion; and in the midst of its kind, between Mercury and Venus; and in the midst of its age, as touching the second work or first whitening, for then it tincteth the perfect white. It is also of aptest putrefaction, that is, of incineration, and of the handling of the soul from the body by putrefaction; and by blinding it putrefieth, and in the aptitude of goodness, or position, that is, of the parts in all their good order, it resteth. And when this is unclean—namely, the Sun, or the blemished Moon, or troubled Jupiter—or if it be not taken in due season, that is, old or young, not yet known, that is, unruled by transmutation into its own water…

And thus he proceedeth, warning that the aptness of putrefaction must be joined with the aptness of goodness of position: which hath respect unto the placing of strong fire, and to the due proportion of vessels.

Moses in the Turba saith of Senio: If the egg compounded be ruled beyond what is meet, then by great fire indeed its light, taken from the sea, is quenched; for it ascendeth to the sides, and is not dissolved, and by consequence is neither congealed nor tinging. Of the due time the same saith: Rule it, and cook it until whiteness appear; and then ye shall see one of three fellows left, namely the water of life, in which are three—fire, water, and air—or the water of life from the body, in which likewise are three.

And Limerus saith, about twelve or eighteen days, so long as there is no sign, and when it is in blackness, even the greatest.

And Morienus saith, that the blood must be broken, lest it hinder; which breaking, that is, separation, is done after it is whitened. And note, if it be ruled longer than is needful, then the body will intrude again; and therefore in due season must it be taken.

And further it followeth: or if it be taken from the lower part of its kind, that is, from other perfect planets…

And Pandulphus in the Turba saith: The egg of the Philosophers, when it is overturned, is against the greater world. For our egg, according to its midst, is called higher, namely from the Sun; but according to its extremities is called lower, namely, the other two parts. For the egg of the world, according to the poles, is called higher, and according to its midst lower; and in the midst is the point of the Sun, as the chick; and in the upper part the same. But in the egg of the world contrariwise: its midst is lower. For example: in the world fire is the subtiler, lighter, and higher element; but in the egg, fire is the lowest, for it is set in the midst. And in the world earth is the grosser, heavier, and lowest element; but in the egg, the outer shells are earth, and the highest element; and so of the rest. Therefore it is true, that the egg hath itself contrary to the egg of the world.

And thus the Philosophers called this art the Egg.

It followeth, the saying of Assiduus: Neither in a strange fire nor with a strange spirit doth it work. For, as the Elder saith: Make not aught alien enter upon it, for it shall corrupt it and destroy the whole. Rather, better to say: it worketh not in another fire, but in its own fire, which is moist. For strange fire is unequal and excessive, lacking temperance. For the whole efficacy of this work consisteth in its own fire, as Morienus and Geber witness. For the heat of the Sun alone generateth the good complexion, which heat the fire of nature doth imitate.

It followeth: When that other is digested—namely, the bird’s water of life, which is the animated tincture—by incorruptions its form is perfected. And after it is whitened, then is it apt for operation. Wherefore it must not be taken before melancholy, that is, blackness, abound in it; nor after it aboundeth. Nor let it be taken before the air, that is, vapour of air, be begotten in it—that is, in the unclean body not yet spirited. And if thou defer too long, then it fadeth. But after it is more perfectly formed, it is apt for operation; before melancholy abound, for otherwise it would work into black and not into red or white.