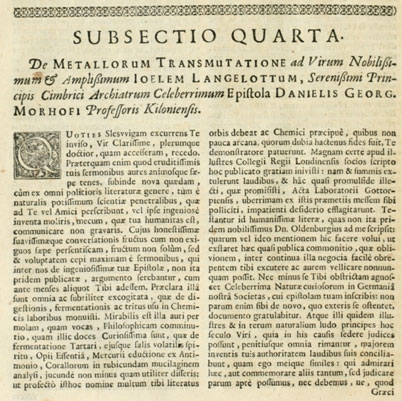

On the Transmutation of Metals - De Metallorum Transmutatione

To the Most Noble and Most Distinguished Man, Joel Langelott, Most Renowned Chief Physician of the Most Serene Prince of Cimbria.

A Letter of Daniel Georg Morhof, Professor of Kiel.

Translated to English by Mitko Janeski from the book:

Jo. Jacobi Mangeti, medicinae doctoris et sereniss. ac potentiss. regis Prussiae archiatri, Bibliotheca chemica curiosa, seu, Rerum ad alchemiam pertinetium thesaurus instructissimus : quo non tantùm artis auriferae, ac scriptorum in ea nobiliorum historia traditur : lapidis veritas argumentis & experimentis innumeris, immò & juris consultorum judiciis evincitur : termini obscuriores explicantur : cautiones contra impostores & difficultates in tinctura universali conficienda occurrentes, declarantur : verùm etiam tractatus omnes virorum celebriorum, qui in magno sudarunt elixyre, quíque ab ipso Hermete, ut dicitur, Trismegisto, ad nostra usque tempora de chrysopoea scripserunt, cum praecipuis suis commentariis, concinno ordine dispositi exhibentur. Ad quorum omnium illustrationem additae sunt quamplurimae figurae aeneae - Subsection 4.

1673

As often as I visit you at Schleswig, Most Illustrious Man, I usually return more learned than I came. For besides the fact that you often captivate my ears and mind with your most learned conversations, you sometimes do not hesitate such is your kindness to share with me certain new things, whether from every field of refined literature or, above all, from the inmost recesses of natural science, which either friends write to you, or which you yourself, with ingenious invention, are working upon. From this most honorable and most delightful conversation, since I often perceive no small benefit, I gained not only profit but also the greatest pleasure from the conversations we had, when a few months ago I was with you, about your most ingenious Epistle, not long since published.

All those matters you set forth there are splendid and most subtly devised: what you noted on the use of digestion, fermentation, and trituration in chemical works; that wondrous comminution of gold by the mill which you call Philosophical, which you there teach; the most curious things which you delightfully and profitably discuss concerning the fermentation of Tartar, the volatile spirit of its salt, the essence of Opium, the extraction of Mercury from Antimony, the analysis of Coral into a reddish mucilage. Indeed, the learned world owes you much for these, and chemists especially, to whom, through your demonstration, not a few arcana whose credibility had hitherto been doubtful were laid open.

Certainly, by the publication of this writing, you have gained great favor among the distinguished fellows of the Royal Society of London: for they both exalted it with the highest praises, and, enticed as it were by this prelude, impatiently demand those Proceedings of the Gottorp Laboratory which you promised, expecting for themselves from those premises the richest harvest. This is testified by the most courteous letters which not long ago the most noble Mr. Oldenburg wrote to me; of which I wished to make mention here, that this might stand as a sort of public reminder, whereby we may sometimes oblige you, amidst your continual occupations, to shake off the distractions that creep upon you, and to prick your ear.

No less, too, will the most celebrated Society of the Curious in Nature in our Germany, to whom you address your Epistle, acknowledge its obligation to you: for it greatly rejoices in this new proof, by which it may display itself to foreigners. And truly, those illustrious men, the princes in this age in the field of natural philosophy, since they can sit as judges in such matters and examine everything thoroughly, will lend their authority with praise to your discoveries, which I, and others like me, can only admire or recount to others, but are little suited, nor ought we, to judge them lest, as the Greeks proverbially say, ἐν ἄλλοτρίῳ χορῷ πόδα τίθησιν, we seem to put our foot into another man’s dance.

Yet it so happened, I know not how, that when recently I received from your hand that most welcome gift namely your most learned Epistle, on the occasion of the dissolution of gold by the Philosophical mill we were drawn into conversations concerning the transmutation of metals; and what things I then put forward on that subject seemed not displeasing to you: so much so, indeed, that you judged them not unworthy of the public light.

These, in truth, were meant to confirm the truth of transmutation, partly drawn from the sanctuaries of natural wisdom, partly from history, both ancient and more recent, as memory suggested to me while discoursing. They were not indeed distinguished nor sufficiently polished: yet, such as they were, they were not unwelcome to you I attribute that to your kindness.

At that time, however, I immediately warned you, not to bid me bring forth new Athens, that is, to write upon a matter worn and almost threadbare by the pens of so many men, and even odious, especially since the most distinguished men Conringius and Borrichius had already long since occupied the whole ground of this subject; and since the crowd of lesser writers is so great, that my effort here might appear to wiser men either inglorious or useless.

But you, thinking otherwise, did not cease to press me, that I should undertake this small task. In which matter, since you so wished, I neither ought nor wished to resist you any longer only see to it that you do not deceive yourself, nor others, to whom perhaps greater hope is held forth by you, be deceived.

We, however, will approach the matter thus: first, that we touch briefly on the possibility of transmutation; then on the authors who have either transmitted or propagated the arcana of this art; then finally, on the very experiments of this art, we shall bring forward into the midst not things entirely trite or commonly known.

Chapter 1.

First, when the question is asked concerning metals, whether they can be transmuted: since transmutation necessarily supposes the corruption of one and the generation of another metal, it ought, at the threshold of this Dissertation, to be examined how Nature composes them in the bowels of the earth.

But who would not confess his ignorance here? For since the matter itself is so deeply plunged into darkness, who shall bring this doctrine into the light? In so many centuries up to this very day none has appeared, though now we discern natural things with eyes so keen, down even to the very particles of particles, who could with an outstretched finger point to the causes of metals and set them before our eyes. Hence everywhere are mere conjectures and gropings, nothing certain: since what we know of their nature arises only from superficial contemplation. Perhaps Nature has hidden their principles deeper than human endeavors are able to reach.

The operations which she employs are slow, and sometimes are extended over whole centuries, and through secret passages, so that they easily escape all the diligence of even the most skillful observer. The metallurgists are unlearned, and ignorant of natural causes. The philosophers, who by deeper insight might probe into them, do not easily expose themselves to the dangers which accompany that business. Hence we have abandoned one of the noblest parts of natural science; and because it has not been sufficiently understood, we shall go astray also in the rest.

For from the inner composition of this earthly globe, and of its chief parts, among which salts and metals claim for themselves, like juices or marrow, the principal place; and from their exhalations, the whole atmosphere which is spread around this globe is variously affected, and many of the phenomena of this atmosphere depend thereon. If you shake down the writers on metals, you will find little that can truly satisfy the mind. Whatever, however, has been accomplished in this matter is due to the Germans; whose footsteps foreigners follow, if indeed there are any who have treated this subject.

There are few monuments in the writings of the ancients Plato, Aristotle, Pliny concerning the history of metals. Among the more recent, after the books De Mineralibus of Albertus Magnus, the book of Andreas de Solea On the Increase and Decrease of Metals (commonly ascribed to Basil Valentine, and usually published together with his Twelve Keys, though he lived a whole century later) is excellently written, and contains many recondite things; but most of them are obscure, and not written with sufficient clarity.

The most diligent and most learned writer is Georgius Agricola, who treated both the history and the operations of metals to the best of his ability. To these may be added the works written in the German tongue: those of Lazarus Ercker, prince in the art of assaying; of Fachsius, Mathesius, Albinus, Zacharias Theobaldus, and the works of Lohneisen, who collected most of his from others. But neither should Andreas Caesalpinus be despised. Bernardus Cesius strays into everything else: for he rather gathered commonplaces about metallic matters, which avail little for discerning the true nature of metals.

Nor should the nomenclators of fossils, found in various parts of the earth, be omitted: Kentmannus, Schwenckfeldius, Cresschmarus, Merretus, Aldrovandus in his Musaeum Metallicum, Wormius, and Athanasius Kircherus how much with great display did he promise in his vast book concerning his so-called Mundus Subterraneus! Yet he sadly mocks the crows gaping after him. For although the book is huge, it is nevertheless so destitute of real matter that sometimes he omits even what is necessary, writes down many superfluities, serves up cabbage so often boiled and reboiled, copies out much from others, stumbles often, and sows new things with a sparing hand.

Far more ingenious than he is the writer of subterranean physics, Beccherus, who in that book and its supplement asserted not a few things which can shed great light upon metallurgy. Nor should Honoratus Fabri and Hamelius, most excellent philosophers, be deprived of their praise: the former in his physical books, the latter in his treatise On Meteors and Fossils, not slightly illustrated this part of natural philosophy.

In the past year Webster, an English author, published in his native tongue a Metallographia, but for the most part compiled from the Germans, and especially from some of those whom we have just enumerated, with a few small observations of his own. Yet he knew not all the authors, nor instituted a sufficiently careful selection. Nevertheless, his diligence deserves praise, by which we now have collected under certain heads what in the authors themselves can be sought not without some tedium.

What the illustrious Robert Boyle has commented on concerning the origin of metals and minerals will, beyond doubt, like all the works of that man, be excellent and most elaborate, so far as can be judged from that little book of his, more precious than the very gems of which he treats, not long since published. But these have not yet come into our hands.

Meanwhile, from so vast a harvest of writers on metals, you will scarcely glean anything that brings the inmost nature of metals into full view before you.

Chapter 2.

Those who make water the element of all bodies, do the same also for the substance of metals. This opinion of certain ancient philosophers was revived among the moderns by Helmontius, Bernhardus, Palissy, and Henricus de Rochaz.

And it is confirmed by that notion, still held by some, of the Catholic solvent liquor, which they themselves call the Alchaest by whose power it is believed that natural bodies, and even metals themselves, may be reduced into a tasteless liquid. This hypothesis has troubled the minds of many, and has heated the furnaces of countless chemists: but all with wholly fruitless labor. For never has there been one who could assert he had seen such a liquor; although there are not a few, as is known from histories, who have more than once seen the Great Philosophers’ Stone itself. Indeed, Helmontius contradicts himself: for in one place he wishes that bodies be resolved by this liquor into pure and limpid water; in another, he says dregs remain. Certainly, before the times of Paracelsus and Helmontius, these things were unheard of in the schools of the chemists: for all other writings of Arnold of Villanova, Lullius, Bacon, and the like philosophers speak otherwise. And if you consider the matter itself, it seems repugnant to the nature of things. For the natures of liquids and of solid things are distinct: and though the latter are sometimes dissolved by the former, the bonds by which they cohere being loosened so that, dispersed, they escape the sight of the eyes, nevertheless they never are changed into each other, nor derive their principle and origin from them.

Bernhard Palissy, a Frenchman, indeed a man of the common sort, but ingenious, in books written in his native tongue on the nature of springs, metals, and gems, wishes that from waters all things, even metals and the hardest stones, are produced. Yet he posits two kinds of waters: one material, the other congealing. If you weigh this rightly, you will perceive a diversity of principles, so that nothing new is discovered here, except the names.

Henricus de Rochaz, his countryman, who wrote somewhat on metallic waters and the secrets of mines, also composed a Reformed Physics. He indeed makes water the material principle of things, but joins salt to it, a principle consolidating bodies. Yet he also admits things nearer at hand in the composition of bodies.

To this same view leans the illustrious man Robert Boyle, in a little book recently published on Gems, in which he holds that their first origin was of liquid substance; which, if imbued with certain mineral tinctures while fluid or soft, acquires colors according to the kind of mineral encountered. In opaque stones, such as haematites, jaspers, and similar pebbles, he thinks that earth impregnated with metallic juices is hardened into the form of stone by the addition of a petrifying liquor, or spiritus petrificus. There are many excellent things in that book which contribute to illustrating this doctrine.

He makes mention here of a certain liquor accidentally found, which was able to dissolve gems. He supposes the earth to be full of menstrua and other liquors of various kinds, impregnated variously from the mines through which they wander; which, by certain chances, may sometimes act as menstrua, and otherwise may concur to the production of mineral bodies. Indeed, even common water, infected as it generally is with effluvia of minerals, is thought by Thurneyser, in his book De Aquis Mineralibus, to be able to do this. He testifies that this argument is more fully handled in an excellent book De Subterraneis Menstruis.

While I recall these things, I bring to memory what Abraham of Porta Leonis, a Jewish physician, recounts in his book De Auro (in which he disputes concerning the virtue of gold in medicine), about the Fabarian Waters near the Rhine: that they contain golden juice not yet concreted by nature, whence arise those marvelous virtues in curing the sick. For he says that no specks of corporeal gold can be seen in them, such as appear in the neighboring waters of the Rhine, which yet lack that healing power. In these, however, he thinks that juice condenses into corporeal gold. Hence he rejects the use of wine, in which a golden leaf has been quenched, because it cannot acquire any powers from fragments of corporeal gold. But whether all these things are said truly, let it be for others to judge. In matters obscure and remote from sense there is only place for conjecture. But if we admit those subterranean menstrua, one might believe they are not altogether nothing.

The same web was recently woven also by Thomas Sherley, physician to the King of England, in a Dissertation which he published concerning the causes of stones. On that occasion he inquires likewise into the origin of all bodies, which he wishes to be produced from Water and their own Seeds. He prefaced this, that he might pave the way for a medical treatise which he was to write on the causes of stones in the human body. Many learned and curious things are asserted here, which pertain to this argument and to the nature of petrification: but our present design does not permit us to dwell upon them.

With the highest care and industry, this matter will be undertaken to be demonstrated by the most ingenious Steno, in his Dissertation On the Solid naturally contained within a Solid, of which he published a prodrome in the previous year, as I think. And from this, as the lion may be judged from his claw, the whole work may be easily anticipated.

A natural body, he says, is either solid or fluid. If the solid is produced according to the laws of nature, he says it is produced from the fluid. It grows when new particles are added to its particles, secreted from the external fluid: but this apposition happens either immediately from the external fluid, or through one or more internal fluids. All this he elegantly illustrates by a comparison of the human body with the products of the earth. He teaches that in all cases the place of production is to be carefully inspected, that is, the neighboring bodies which contribute to the shaping of the figures of the inclusions. Thus, in the examination of rocks, he judges many things can be discovered which in the examination of the minerals themselves are sought in vain: since it is very probable that all those minerals which fill the spaces, fissures, or dilatations of rocks, had as their material the vapor expelled from the rocks themselves. Whether this is of perpetual and undoubted truth, I leave undecided, for fissures can also be filled otherwise than by vapors expelled from the rocks themselves.

Concerning the production of Crystal, he inquires with much subtlety: whether between fluid and fluid, or between fluid and solid, or indeed in the fluid itself it is produced. For he has no doubt that it is produced from a fluid; yet he denies that it is concreted by cold, or burnt into glass by the force of fire from ashes. For he thinks that not only by the force of fire is the production of glass made, but that it can also be done without the violence of fire and by human artifice: provided one institutes an accurate analysis of the rocks, in the cavities of which crystals are best formed. For it is certain that as crystal is concreted from a fluid, so it can also be resolved back into fluid, provided one knows how to imitate the true menstruum of Nature. Nor does it stand in the way that bodies, from which the whole menstruum has been driven out by the force of fire, can no longer be resolved: since there is another reason for those coagulated bodies which are concreted in a fluid menstruum, of which parts remain between the particles of the coagulated body. For the fluid in which the crystal grows bears the same relation to the crystal as common water does to salts. With glass prepared by the violence of fire the case is otherwise: for almost all its moisture is expelled.

I also recall, however, that even in common glass there can be obtained a certain singular liquor, which at least for a time renders it flexible, if it does not dissolve it: so that images may be formed from it, or characters impressed upon it. I made mention of this in my Letter to the Most Learned Mr. D. Major, written on the glass cup broken by sound. I add that, since the body of glass is composed of diverse bodies already concreted, which can each only be resolved by their proper menstrua, it is very likely that no menstruum can be given which would act upon bodies thus joined together.

To illustrate this doctrine, the history of artificial gems made through water and coagulant powder, which I mentioned in that letter, wonderfully contributes. I shall not recount it here, since your own Dissertation, published a year ago, and now in everyone’s hands, has already made it known. Light can also be added by an experiment I saw when I was staying in Amsterdam, at the house of the physician Birrius, not unknown through his published books in chemistry. He showed me certain little stones, sufficiently pellucid and elegant, and polished after the manner of gems, which he said he had made from a certain liquor which he displayed. That liquor was far more ponderous than ordinary water, though in clarity and transparency it equaled it. It tasted, however, of something faintly styptic and saline. He held it not only as a notable medicine, but also claimed he could effect marvels in the dissolution of bodies with it.

When he poured a few drops of it into Rhine wine, the wine gradually passed, after some interval of time, from yellow to a deep red color; and, if I rightly remember, even crystals sank to the bottom. I did not doubt that it was made from Tartar salt, for I detected a similar taste though he concealed these secrets. From this liquor, when he had precipitated a powder, he exposed it to vitrifying fire until it condensed into a substance similar to crystal: from which he had had those gems formed for himself.

Of their hardness I cannot speak with certainty, since by neither touch nor sight could it be determined. If they did not surpass, at least they equaled the hardness of glass, since they were able to endure polishing.

Of the bodies which approach more nearly to the nature of metals, Steno holds that especially the lamellated bodies have concreted in a fluid and from a fluid. In this class is Talc, whose solid body, he says, can be resolved into fluid, since it is beyond controversy that it concreted from fluid. But those men err farthest from the truth who try to wring this gift from it by the torture of fire: for Nature (he says) has been accustomed to treat Talc more gently, and he is indignant at such cruelty among lovers of beauty; and in revenge Talc yields to Vulcan only that part of itself which it keeps enclosed, of its own resolving power.

Finally, even the more perfect metals might seem to have their origin from a certain liquor, if true be what Franciscus Lana reports in his Prodromo all’ Arte Maestra, ch. 20, which he claims to have been taught by experience. His very words, that fuller faith in the matter may be given, I will here adduce:

“Non direi questo, inquit, se io medesimo non havesse havuto fortuna di havere aliquanta di una simile miniera, dalla quale, con non molto artificio fu cavata una poca quantità di certo liquore aureo, che era la vera semenza di oro, ma per non esser conosciuto, tutto fu consumato congettarlo sopra una quantità di argento vivo bollente, il quale tutto subito congelossi, e accresciuto il fuoco restarono cinque parti di esso perfettamente fisso, cioè, a dire una mezza oncia di quel liquore fisso, due oncie e mezza di argento vivo; che se fosse stato maggiormente depurato e poi congiunto come anima al suo corpo proportionato, sarebbesi con esso potuta formare la vera pietra, ma sin hora non ho mai potuto ritrovare altra miniera simile a quella.”

That is: “I would not say this, unless by good fortune a certain mine (of gold he is speaking) had supplied me with some of it, from which, with no great artifice, a small quantity of a certain golden liquor was extracted, truly the seed of gold: but because I did not understand its worth, all that liquor was consumed in projection upon boiling argentum vivum, which was immediately congealed, and, fire being increased, five parts of it remained perfectly fixed: namely, half an ounce of that fixed liquor, two and a half of argentum vivum. Which, if they had been more purified, and afterwards united as a soul to its proportionate body, the true Stone could have been formed from it. But up to this day I have never been able to find another mine like that one.”

This author writes with great confidence; but the faith of these things let rest with him. Whether he truly extracted from a mine such a liquor as could fix argentum vivum; whether thence it had the seed of gold; or whether from the mingling of those bodies the Philosophers’ Stone (Lapidem Philosophorum) could be produced let each one judge.

For our part, that we may at last bring forward our own opinion concerning these views: we hold that neither gems nor metals can be produced from water alone, taken simply. Metals, because they are corpora secunda mixta, what some call decomposta, in their constituent parts first mingled, perhaps acknowledge a primordial liquor; but one which does not appear in the very production of metals, and is useless for producing metal by art. But of these lower matters we shall speak further below.

As regards the concretion of gems and crystals from water, the matter does not yet seem to me sufficiently cleared up. For although, because they appear to have a simpler texture, by reason of their transparency, they may seem to approach nearer to the nature of water, nevertheless many doubts press upon the matter, which persuade that it may be otherwise. Be it so, that they are pellucid: but they are also hard, and brittle: which may be a sign that there is less moisture in them than in the metals themselves, whose ductility clearly shows a thickened liquor within.

Bernhard Palissy, who wishes them to be produced from water, thinks they are not composed of simple water, but of gems, one of which, which he calls congelantem, is nothing other than Salt, as Sorellus explains, or some other stony substance, different from the nature of water: so that even from his very principles it is clear that crystal is not a body ὁμοιομερές (homoeomerous).

The mixture of common stones is sufficiently shown by that observation of Peireskius, related by Gassendus in his Life of him: who drew out of water a viscous slime, which, upon contact with air, passed into stone.

What hinders, that even in crystals and gems, diverse juices or earths, but of purer nature, may be mixed? But in the cradles of crystals, most ingenious Steno found traces of waters, whence he judges them to have concreted. Yet perhaps those served in the place of vehicles, which carried the constitutive natures of the gems to those sites, but remained outside the body itself. Nor would I myself think it a sound argument to draw from this: that since crystals or gems are dissolved by this or that liquor, therefore they are composed of liquors. For I believe that many liquors can be found, or prepared by art, whose particles are so fitted that they pervade the spaces of certain compounds, and by their structure dissolve them yet contribute nothing at all to their constitution.

By a certain accident in England there was found a most gentle vegetable liquor, which, pervading the hardest marble, tinged it within, in the innermost particles of the substance, with colors that had been admixed.

Berigardus, as he relates in his Circulus Pisanus, p. 534, dissolved pearls and many other things easily with that weak phlegm which first drops from the sharpest vinegar; but with that other, which is drawn out by the utmost force of fire, much sharper and more highly colored, he effected nothing. Yet from those liquors neither marble nor pearls owed their origin.

Even if we had that liquor, from which crystal either concreted or from which its substance was precipitated, yet I would not believe, as the very subtle Steno thinks, that it can be resolved again into liquid nature.

Finally, this too may seem likely to someone: that gems, if not all, at least some, might be compacted from diverse bodies by more violent fire, in the same way as glass is made by us.

Certainly those who profess the art χοστοποιητικὴ also teach that gems may be fabricated by fire, if I rightly remember; and they display before the eyes a kind of image of them, those adulterated ones, the preparation of which Antonius Nerius describes.

Chapter 3.

There are others again who derive the origin of metals from Salt. Yet those who think thus, do not all think the same. For some invent a certain universal Salt, by which they hope to effect I know not what miracles in all Nature, and even in the mineral kingdom. This opinion first gained strength in the time of Paracelsus, and was propagated down to these times by some of his followers, and by the Fratres Rosae Crucis. There also exists a specious book On the True Salt of the Philosophers, written by the Frenchman Nuisement, and translated into Latin by Combachius, where that opinion is both proposed and defended.

That salt they call heavenly, aethereal, aerial, universal: which they extract either from dew, or from air, or from nitre, or even from the excrements of animals. Whether such a thing exists, I certainly would not dare to define: assuredly the older school of chemists knew nothing of it. That salt can be extracted from air I would not deny; but that it is universal, I can scarcely believe. Saline particles of various kinds wander in the air, which, subtilized by subterranean fires and by the heat of the Sun, are carried up into the atmosphere, according to the nature of the underlying soil which supplies them: nitrous, vitriolic, or of some other kind, either singly or mingled together. Yet I would not ascribe to them universal or catholic powers.

Here, by occasion of this Dissertation, it conveniently occurs to me what I saw at Amsterdam, with that most ingenious man Theodorus Kerckringius. He showed me a considerable quantity of true and genuine but impure vitriol, which he had extracted from the air of Amsterdam impregnated as it is with many effluvia of saline waters and marshy soil by means of a certain machine. Truly great instruments of Nature’s Architecture are Fire and Salts: but various, as bodies and mixtures of bodies are various, whose ministry she employs, according to the disposition of the subjects, in their composition and dissolution. Yet they do not enter into their very essence.

Marvelous changes Nature produces in bodies, both metallic and others, by the help of salts, which, through subterranean channels, she scatters in disorderly fashion through the whole frame of the earth, and through all the veins and mines of metals. Whence it is that various small bodies of salts and sulphurs are usually found together in mines: which, however, one would scarcely dare to say pertain to the constitution of metals themselves.

I saw in England a Brabantine, who, by the moderation of fire alone, without any addition of another thing, could produce from the ore of Saturn [i.e. lead] true vitriol, true sulphur, common salt, nitre; he could also prepare vinegar, tincture, and many other things. This art, however, as a most secret matter, he intended to sell for no less than 200 aurei. He had received it from a certain Doctor at Paris: not to be despised, indeed, but of no consequence for the sum of metallurgy. For the metallic body was not composed from those things, which had only by chance flowed together at the place of the ore. From other materials he might perchance have produced other results; though he had tried the experiment only in the ore of lead and antimony. The ores of gold and silver, I think, he would not have overcome by his artifice.

Indeed, in every soil there is a peculiar saline substance, either singular or mixed with others, which difference a certain blind sailor was said to be able to detect by taste, as a most trustworthy man told me. For when a lump of clay was thrown into the sea near the land, the earth which adhered to the lump, being tasted by him, he could name without error the place where they were.

Hamelius, De Fossilibus, book 2, chapter 9, seems in some way to favor this opinion: for he makes the first rudiment of metal to be a certain false substance, soluble in water, which is gradually cooked, and at length no longer fears the injuries of air or water. But these things are said as mere conjecture, and without any show of truth. For what was that false substance? He himself cannot name it, nor is there any among the known which could serve that function.

Chapter 4.

There are, moreover, those who, leaving aside that universal salt which they seek everywhere and find nowhere descend to the known and common kinds. For when they see the powers of nitre, vitriol, and common salt in dissolving metallic bodies, they suspect that some other hidden arcana lie concealed beneath them. Their spirits are encouraged by those countless little stories which they have either heard by report, or read recorded in writing. Such are those of silver extracted from lead by the aid of spirit of salt, as reported by Johannes Fridericus Helvetius in his Vitulus Aureus; or of a good quantity of gold drawn forth from a certain Hungarian vitriol, as reported by Beccherus in his Physica Subterranea. These, however, happened rather by the separation of silver and gold already latent, than by any singular ingeneration. For I do not wish to call into doubt the faith of those men who have handed these things down to memory.

And I confess that I am not quick to believe what Salomon de Blauenstein for thus he undoubtedly calls himself in writing, and openly professes himself a true disciple of the art χρυσοποιητική has set forth in his Interpellation to the Philosophers concerning the Philosophers’ Stone against the Mundus Subterraneus of Kircher, chapter 2. There he says: “Why say more? I also could give another Epicherema against Father Kircher, if only he were present with me for three hours, and I could provide him, though incredulous, something to touch with his own hands: how from pure fine silver, entire and whole, pure fine gold is made by the addition of simple prepared salt, without any the least other addition.”

What he means by his simple prepared salt I do not know. If he means common salt, I admit that nothing more astonishing could be imagined, which so greatly contradicts the principles of the older chemists. Above all, some have labored to madness over vitriol and nitre. Some have filled entire volumes with these things: and though they themselves were blind, yet they wished to show the way to others, twisting into their own sense the sayings of the chemists, which they, deceived by the variety of names, did not rightly understand, nor could interpret correctly from the consensus of the authors for the names of Vitriol and Nitre in them signify something other than what these men suppose.

How many so-called “processes” are circulated by impostors from vitriol! There exists also a Process from Vitriol by one Jodocus V. R., which is usually added to the works of Frater Basilius Valentinus, described with great display and labor, promising the highest medicine of men and of metals: but a friend of mine, who had operated according to its prescription, found it false in every respect, except in the very effect itself. The rest in it are fairly well. What a noise did Glauber make with his nitre, from which in so many books he promised miracles with wide open mouth! Many things in him are excellent and splendid; most are the offspring of ingenuity rather than of the heat of furnaces. Yet golden mountains we have not seen. In many things, however, Hamelius, in his De Fossilibus, follows his authority though he ought first to have tested it.

I do not deny indeed that astonishing effects in nature may be produced by these salts, and especially by nitre: but that they can produce the metal itself I doubt. For plainly it belongs to another family of minerals, and is not by nature fitted for constituting that slow and viscous metallic humor. Meanwhile, if they appear under the form of a sharper spirit, they exercise a tyrannical power upon those bodies; if, however, reduced by a gentler fire into a subtler and more benign nature, they even seem to elicit tincture from gold itself, and to carry it with them through the alembic. These things may perhaps be of some use in medicine; but in the amendment of metals, since it belongs only to corporeal nature, it is ineffective.

Some speak everywhere of the marvelous powers of the subtle spirit of nitrous salt extracted from May dew. They write that with the spirit and oil of this salt, which is prepared from May dew, those at the point of death may be recalled, and tincture may be drawn forth from gold.

It is astonishing how Borellus (Centuria 1, Observation 6) triumphs in this secret, which he investigated more deeply: “After many labors and vigils endured in searching into nature’s arcana, I at last obtained the secret of dissolving gold, that is, a benign menstruum, which kindly dissolves gold within a few hours, and without smoke indeed without fire dissolved it can be reduced to the nature of a salt and of an oil; of which 3, 4, or 6 grains, administered according to different ages, within about four hours by copious sweats cured malignant, purple, epidemic, and obstinate fevers.”

But let the readers know, he adds, that this was effected by the spirit of dew, according to the doctrine of Sendivogius. Many will say: why then do I not procure a supply of it for myself? But let them know that the expenses surpass the profit. It is noteworthy (he further adds) that the gold collectors of the river Gard, near the town of Vigan, affirm that drops of dew adhere every morning to each grain of gold in the sand, and that they are nourished thereby. This dew, by long digestion, I rendered black, then very white, and then citrine; but it did not produce projection.

He afterwards added some particulars about the method of preparation, which you may read there. Moreover, it has been observed that if leaves of gold be cast into the dew itself not into the spirit of it and digested with it for some time by a gentle fire, they at last disappear; but when afterwards the dew is filtered, there remains at the bottom of it a substance like wool or snow, of the happiest use in affections of the heart. Some ascribe this to the dew or to the spirit of dew; others to the spirit or essence of honey, which itself also consists of dew. For it is said to dissolve gold and to seize its tincture through the alembic, which may be like potable gold (aurum potabile), and may accomplish marvelous things in the transmutation of metals.

And I myself saw some tincture of gold prepared in this way by a man who, hoping for I know not what treasures from it, had sold this secret at a high price to a certain prince. But if anyone wishes to know it for free, let him consult Johannes Nardius Florentinus, Disquisitiones Physicae de Rore, chapter 23, where he teaches the mode of preparation.

Mathesius Sareptensis, Concio 3, observed that a golden coin, sprinkled several times with dew or May rain and dried by the Sun, or buried in the earth, became heavier. Yet although all these things are spoken of with enough plausibility, they do not move me to assign any part, either to nitre or to the spirit of dew or of honey, in the making of gold, or in dissolving it radically. Those liquors, or rather the salts mixed with liquors, act only in the ordinary way, as all corrosive waters do: but because they are more attenuated and subtle, they also tear away subtler particles, which the alembic can drive over without any trouble of fire, yet not disjoined from their own natures.

This is my opinion concerning nitre, or the nitrous salt contained in dew, with regard to operations upon metals: though I am not ignorant of its great powers in the generation of Vegetables and Animals. I will produce a notable example of it, unless you, Most Noble Sir, dislike such a digression beyond the bounds of our argument. That eels can be produced by art, I had neither ever heard reported, nor read in any writer of natural history; but I learned on my recent journey that farmers in Belgium accomplish this by the benefit of dew. At first I refused to believe the tale: but afterwards I came upon the writing of Abraham Mylius, On the Origin of Animals and the Migration of Peoples, and I read of the same artifice there, book 10, p. …, whose words I will quote:

“In the month of May, when there is heavy dew, cut and dig up with a hoe from a grassy field two equal turfs before sunrise, and place them, grassy sides together, on the bank of some pond on the north side, where the Sun casts its rays most strongly. You will then see, after a few hours have passed, a swarm of young eels as it were sprouting forth. In this way one man, not without profitable success, has generated in his ponds a great number of eels.”

And this experiment seems likely, because in eels no seed is ever found, nor any organs of generation: so that much debate has arisen among writers of Natural History concerning their origin. If you ask fishermen, they teach that they are produced from certain small worms which are generated at a fixed time of the year in the flesh of all kinds of fish. I myself have more than once discovered these worms.

You may also read in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of England, p. 35, the observations of Thomas Henshaw, a noble Englishman, concerning the generation of worms from putrefied dew. And I myself recall that the generation of bees from putrefied hydromel was noted by someone.

Finally, to dew alone must be ascribed that resurrection of plants from ashes, concerning which Caramuel and Hardtoffer have written in their books; Voigtinus in a special Dissertation has treated it; and Kircher promised to make an entire book out of it. Great therefore is the power of this salt in the production of vegetables and animals: but though metals may be vexed and variously affected by it, they cannot be improved, changed, increased, or made fruitful by it, as is the case in vegetables.

Chapter 5.

From the family of salts we proceed directly to the metals. Among these, the first of all to be addressed is argentum vivum (quicksilver), truly a marvelous substance, which fashions and refashions itself into a thousand forms, in whatever way it is treated by art. Pliny calls it the vomica of eternal liquor: for it is liquid and flowing. And since with wondrous love it embraces gold, and unites itself with it most intimately, and seems beyond the other metals to be only another humor and the rudiment of a metal, very many, indeed, have thought that they discerned in it the first being of the metals, so to speak. Nor are there lacking today those who assert the same though not made wiser by the shipwrecks of so many in that sea.

Added to this is that venerable name of Mercury, which occurs so frequently in the writings of the chemists: so many descriptions, so many requisites conspire together, that even the most cautious are deceived by them. Some will have the Virgin Mercury, produced by Nature herself, not yet tried by voracious flames; others, that extracted by art from the other metals. Whether this be possible has until now been doubted; but the truth of this artifice was shown in your Epistle, Most Illustrious Sir. Yet I judge that this differs in nothing from the vulgar mercury, whatever others may think.

For since marvelous, and almost imperceptible, is that dissipation of Mercury into the smallest parts, which happens in mines by subterranean fires, it readily insinuates itself into and mixes with metals but not radically. Some of its particles vanish into the air at the first fusion of the metal: those which cling more tenaciously remain, and at last are drawn out by the help of salts, and separated from the rest of the particles. This is more easily done in ores into which it has entered more freely, and from which it is more quickly expelled. When by fusion the metallic particles are more closely joined, all things succeed with greater difficulty.

From Antimony and lead it can be extracted not without ease, more easily still from its own ores. Grind the ore of lead into fine powder, and move a golden stylus in it for a little while, and particles of Mercury will at once adhere to the gold. Nor does it mix itself only with metals, but also with wood. I had from a friend a piece of wood, cut from a tree grown in metalliferous soil, in which throughout all its fibers and veins were disseminated particles of argentum vivum, so that by vigorous shaking they could even be dislodged which was easily done, since the paths in wood are looser than in metal. I showed it, when I was in London, to the illustrious Robert Boyle, who believed that such wood could also be produced by art. But be that as it may. Yet in the same way, namely by sublimation, this is effected both by Nature and by Art.

The author of the book L’Europe Vivante, tome 1, part 2, relates, on the report of a certain English nobleman, the case of a workman who had long labored in the mines of Mercury, into whose whole body its minute particles had so penetrated, that a piece of copper grew white at the breath of his mouth or the blowing of his fingers, as if the very body of Mercury had been rubbed upon it. I therefore altogether believe that those are mistaken who, because they see Mercury can be drawn out from metals, at once think that metals are composed of it intrinsically. Yet I confess that the arguments we have set forth above are so specious, that they may easily draw someone into that opinion.

But from so many experiments nothing has yet been accomplished, and with one voice all the more prudent chemists cry out: that they have nothing to do with the vulgar Mercury, that they do not want argentum vivum currens, which Lullius somewhere calls the subventanean egg, but another metallic substance, immature yet not impure at its root, which they call their own Mercurius: that without this, common quicksilver has no use in the transmutation of metals.

This I could confirm by their countless statements, did I not know these things to be already familiar to you. Yet I know some who, by the so-called particular way, boast of having made from argentum vivum a nobler metal though without profit. Of which I shall speak in what follows. How many labors, moreover, have been expended upon Antimony, from which not a few hoped to obtain that greatest secret of Nature! But in it there is no genuine metallic Mercury, such as is required for composing the most perfect metallic bodies: as is plain from the fragility of its texture. Perhaps there is hidden in it some portion of purer sulphur, whence a certain particular transmutation may be granted. This seems to be hinted at by Basil Valentine in his Triumphal Chariot of Antimony, and by his commentator *Theodorus Kerckringius. For to the Great Work, by their own confession, it contributes nothing. Yet most useful remedies lie hidden in it, especially for diseases arising from infection of the blood, which it has power to subdue almost miraculously. These Basil Valentine extols even to the skies with praises, and Kerckringius confirms by his experiments.

There are not lacking those who, either from one immature metal, or from the union of two one perfect, the other imperfect by long coction alone, which imitates the subterranean operations of Nature, think to produce a more perfect metal: since metallurgists discover in Nature that the ores of lead, in process of time, are changed into silver. In this opinion was that most sagacious investigator of natural things, Bacon of Verulam, who in the Historia Naturalis, Centuria 4, prescribed a method by which it seemed to him possible to transmute a baser metal into a nobler.

After he had listed the requisites of this work, finally, at number 327, he prescribes the process in this way: “Let a narrow furnace be prepared, and a temperate heat be excited, such indeed that the metal may be perpetually melted and preserved, but not a more vehement one; for this is most conducive to the matter. Let the material be silver, the metal which most symbolizes with gold, and let one-tenth part of quicksilver (Mercurius vivus) also be added to it, together with one-twelfth of nitre, in just weight, which serve by enlivening to open the body of the metal. The operation must be continued for at least six months. I wish also that oily substances be sometimes added, such as are employed in recovering gold, when it has been embittered by the torments of separation; in order that the parts may be more lightly and closely disposed. This is of great importance to the undertaking. For gold, as is well known, is the most compact, of all metals the heaviest, and the most flexible and extensible.”

So Bacon of Verulam; and a friend of mine in London confirmed to me that he had truly held this opinion. For although in his writings everywhere he speaks but lightly of the study of metallic chemistry, yet in his private studies he most diligently treated of the matter, not without great expense, and by that very method which he here prescribed to himself. But he effected nothing at all, nor indeed could anything be effected by that path, as anyone skilled in these things can easily perceive.

So also Fr. Lana, in the passage we praised above: he supposes that gold amalgamated with Mercury, if long digested by fire, is at length changed into the Philosophical Elixir. Yet this is not to be despised, that Bacon required exact regulation of the fire: by this alone sometimes more is accomplished than by six hundred other aids. Wherefore nothing do even the older chemists more insist upon, and I myself know many of his experiments to be quite successful.

Who does not know that the calcination of Talc is reckoned a most difficult matter? Roast it in the greatest fire at pleasure, and even for a long time, and it will stubbornly elude all the force of the flames. Yet I have seen within half an hour, by a very small fire, and with rude artifice to the eye, its whole substance so calcined that, the yellow color being taken away, it became spongy, and under the fingers could be crumbled into the finest powder. Hence it is clear that Talc is not so indomitable by fire as some have believed, who thought they had discovered in it something like gold, especially in the yellow.

In which opinion they were not altogether wrong: for even today metallurgists know how to separate gold from it, and there lies hidden in it a purer sulphur than you might suppose. And a friend once told me that he knew a physician who, with sulphur extracted by a singular artifice from this body, was able to cure incurable diseases, and placed it in the highest rank, next to the greatest Elixir. This is also attested by Martinus Martini, in his Atlas Sinicus, p. 79.

Talc reduced to lime and mixed with wine is received by the Chinese physicians as a singular medicine for prolonging life. From this experiment, therefore, it may be seen how often also in the kingdom of Vulcan:

Tranquil power accomplishes

What violence cannot;

how sometimes gentler flames prevail over harder bodies, while stronger ones are resisted. To this dissertation, since I am now upon it, I will give further attention, and unless my talkativeness be burdensome to you I will confirm it by most choice examples; although not all from near at hand, yet some from afar may nevertheless illustrate our subject.

When I lived at Amsterdam, Theodorus Kerckringius confessed to me that he had made from quicksilver (argentum vivum) both true silver and true gold. For he showed me four metallic pieces, equal in thickness to a man’s finger-ring: the first like tin; the second like silver; the third was yellowish; the fourth in color answered to gold. These were made by the mere regimen of fire, from argentum vivum, with the addition of a certain very small powder (which I suspected to have been made from Antimony, nor did he himself seem to assert with certainty that it was otherwise). And it appears that he himself, in some places of his Commentary upon Basil Valentine’s Triumphal Chariot of Antimony, hints at this.

I also saw at the same man’s workshop a remarkable artifice: that amber could be dissolved by the mere ministry of fire, with no other thing added. For he showed me the corpses of infants coated with amber, so that all their members were transparent. He also showed me a glass phial filled with such amber dissolved and then congealed again. How splendidly thus the bodies of great men might be embalmed and preserved from putrefaction! For without any evisceration of the bodies, against all injury of air and moisture, in this new tincture of amber they would lie as if clad in armor.

What profit might not arise from this invention, since fragments of amber the larger they are, the more precious they are esteemed, and in the East they are valued beyond gold could thus be produced here in whatever quantity one wished? Therefore that which in so many ways was attempted by the most ingenious chemists, is now owed to the regimen of fire alone. Long and much, I confess, have I exercised my mind in investigating the nature of amber: and indeed the novelty of this invention compels me, though the matter be somewhat foreign to my theme, not to withhold myself even now.

Concerning the origin of amber, the matter is uncertain. Some regard it as the offspring of the sea; others, who judge that it proceeds from the earth, whose opinion seems to me the more probable: for terrestrial animals and insects are found enclosed in amber everywhere; a matter which our most illustrious colleague Dr. Major will one day explain more fully in his book On the Non-Maritime Origins of Amber. But in truth it is frequently produced in places where Pines and Turpentines grow, which might be an argument that it arises from a certain similar viscous substance, such as is found in those trees, dispersed through the earth, and coagulated by saline particles of the neighboring sea, or from elsewhere. For many things argue a nature almost the same: its inflammability, and its odor, which differs little from that of burning Cyprian turpentine; and the fact that from the juices of those trees by art amber can be made, as the Chinese even today make it, according to the testimony of Martinus in his Atlas Sinicus, p. 65.

He says that some think it arises from the clarified marrow of pines, hardened and rendered pellucid over long time. And I indeed saw that from pine-pitch or resin by decoction it can be made by art, and so excellently separated by the Chinese, that it might provoke envy of the genuine. I myself judge that an oily humor of very similar nature can be dissolved.

Impure amber also can be corrected and refined by art, as Glauber teaches in his De Furnis Philosophicis, by spirit of salt rectified: but then it loses that hardness, and will endure only in a cold place, or moderately warm. If the heat is more intense than is fitting, it melts and is dissolved. I know men who tried this experiment with good result: if only anyone knew another art by which amber could again be solidified, he would then be superior to Nature’s arts. Yet even Nature sometimes presents it in an unelaborated form, such as was that piece which was soft on one side, hard on the other, and upon which the most noble Oldenburg was able to impress his seal, of which he himself makes mention in the Philosophical Transactions, p. 2061. Nature also is wont to paint it with various characters, such as the piece lately sent to me by the most noble Johannes Tintorius, Councillor of the Most Serene Elector of Brandenburg, in which the letter D was drawn by a clear line of Nature, and, being most courteous, he promised to send me also other letters of the Alphabet so delineated in amber.

Since therefore I judge this opinion of the origin of amber most probable, I think the author of the book L’Europe Vivante is deceived, who in tome 1, part 2, supposes it to arise from honey, which, collected by bees on the stones of the shore of the Indian Ocean, after the cooking of the Sun, falls into the sea, and, clothed with sea-salt, is cast up by the sea upon the shores of other regions. He cites the authority of some chemist, who found in fractured amber a soft substance similar in taste to honey, and which, after its solution by spirit of tartarized wine, still remained. But anyone can easily see that all these things are absurd, so that it is not worth while to dwell on them. But enough has been said about amber, on the occasion of its solution, which is effected by fire alone. Let us now return from this digression to our path namely, to the use of fire in chemical labors, if rightly administered.

Of which I would here repeat another example, mentioned above, of the Brabantine, who by one artifice of fire was able to draw forth almost twenty different things from a single ore of Saturn (lead). But how, without fire, any spirits whatsoever may be drawn from animals, plants, woods, stones, and other bodies, or their parts a procedure proposed by Magnus Pegelius in his Thesaurus Rerum Selectarum, p. 109 that remains buried among his other arcana. For (to note this in passing) that author, who was a physician and philosopher at the University of Rostock, published in 1604 certain Lemmas of singular inventions, both physical and mathematical, among which were many either conceived or indicated by him, which in our time have been discovered and brought to light by others.

Chapter 6.

Furthermore, those who do not find the causes of metals in the earth attempt to derive them from the heavens, or at least to deduce the principal part constituting them from there. Hence certain Planets are assigned to certain metals, to which they are believed to owe their origin, and they are even greeted by the same names; so that we may have, as it were, new subterranean stars. Although this opinion is attacked by some, because no evident reason can be given for it, yet it is by no means to be utterly despised, since it is not born merely from χρῆς ἢ πειθών [necessity or persuasion], but defends itself by its antiquity; as the most learned Borricchius shows in his excellent work On the Origin and Progress of Chemistry, whose coffers I will not pillage. That in the great globes of this world especially the planetary ones whether as a whole system, or in their nobler parts, among which in the terrestrial globe the metallic spirits must absolutely be reckoned, scattered through this vast body, there should be no sympathy or mutual efficacy, no one will easily persuade me. But since the faculty of observation extends beyond human ingenuity, we cannot define anything accurately; yet neither ought we to explode and reject what we find handed down by others, especially by the ancients, concerning it.

We readily perceive the powers of the Sun and Moon upon these lower things. To the former commerce with gold, to the latter with silver, is vulgarly attributed without now saying anything of the other metals. The similarity between Sun and gold is shown by their splendor and heat, which proceeds from sulphur most perfectly digested, and which is believed to be instilled into this metal by the Sun. If we are willing to listen to the opinion of Honoratus Fabri, which however he pronounces as a hypothesis: the very substance of the Sun consists of gold melted. It is therefore no wonder if it also scatters these seeds through the earth, and produces therein a substance similar to itself. Digby reports but from the word of a friend that the rays of the Sun, through glass and concave vessels disposed in a certain way, were precipitated into a purple and most minute powder. Who, when he reads this, would not, with the credulous, exclaim concerning the sulphur of nature? But he who told this to Digby deceived himself with pleasing illusion. For in the air there always float particles, either saline or of some other kind, which, collected by this mirror-fire and burnt or calcined to redness, appear in such a form. Already Paracelsus had written of a Solar powder collected from mirrors by the rays of the Sun, by which, duly prepared, we might excite the fiery nature within ourselves, and enter into some commerce with fiery demons. But these are impostures.

The vulgar opinion concerning the Sun is, that it generates gold in lead and copper, with which temples and houses are wont to be covered. Though Honoratus Fabri calls this an old wives’ tale, I yet know men who, from old lead and tin, by repeated calcinations and reductions, have extracted no small profit of gold and silver; whether it proceeded from certain hidden causes, or whether it was merely separated.

For as to lead and copper laid up in roofs: by continual rains, in which lie hidden the most subtle saline particles, and by the heat of the Sun, in those metals (since no metal is altogether solitary) something of purer metal might have been matured. Albinus, in his Chronicon Metalicum, p. 29, observes that in the mines of Schneeberg, abundant silver was always found under the entrance of Saturn into the sign of Cancer, with the Moon assisting. Concerning pearls, Garcia ab Horto reports that those taken after the full Moon diminish and decay with time; but those taken before the full Moon are not subject to this defect. Is it not well known concerning gems, whose watery blemishes undergo changes with the Moon? We perceive the powers of the Moon in the bodies of animals and in vegetables. These Isaacus Vossius in his book On the Motion of the Sea tried with many arguments to refute yet Experience teaches otherwise.

Chapter 7.

We shall now enter the game of the Chemists and listen to their oracles. They are ever inculcating upon us their Mercurius and Sulphur. If you examine what lies hidden under these names (for they do not wish them to be taken in their vulgar sense), they will thrust upon you six hundred words, obscure and enigmatic descriptions, in which one must hunt for meaning, and gather them together, as it were, like the torn members of Hippolytus, from here and there. Yet when you have done this, you will find a consensus among them except that the most recent sect of Chemists, after the time of Paracelsus, added to those two, Mercurius and Sulphur, a third principle, namely Sal. I do not wish here to discuss at length the number of these principles, whether they belong to every body, and how much they differ from the common principles; for this has been most learnedly and copiously disputed by the illustrious Robert Boyle in his Sceptical Chymist, and by Hamelius, in his book On the Agreement of the Old and New Philosophy, lib. 2, c. 4. The ancients, before Paracelsus, did not establish these two as common principles, as our moderns would have it, but only as metallic principles. In this matter, I think they are to be heard before others, since by actual use they more correctly learned the nature of metals, than those who follow only their own reasonings and opinions.

Those more remote principles of bodies, namely the elements and atoms, they did not consider to belong to their art: for metals are not immediately composed of these, and it is given only to Nature herself to produce something from them. Closer principles, however, can be handled by the hands of men and drawn into some work. If you read their books carefully, and compare their opinions with one another, you will see that they do not teach absurdities, but things which can be reconciled very well with the schools of the ancient philosophers, Plato and Aristotle as Hamelius, in De Fossilibus, lib. 2, c. 9, has reconciled them, having there gathered and judged the various opinions of different philosophers concerning the generation of metals; so that we may spare ourselves that labor.

By Mercurius and Sulphur they do not mean what we commonly so call: for those, rather, are metallic dregs to them, than true principles. Mercurius, or rather argentum vivum, so far as we can gather from their writings, is to them a metallic substance from the family of the more perfect metals, immature, most fluid with gentle heat, ponderous, volatile, supremely ductile not the running quicksilver of the vulgar, but the one and highest agent of metallic nature. This they describe under six hundred names, yet by no single one do they call it or demonstrate it. This, they say, is found crude in Nature; whence, by the highest art, they draw forth a most pure, viscous substance, which is a nearer material for constituting metal. This indeed is a principle common also to the other metals; but according as sulphur purer or more impure tempers it, it acquires this or that mission, whence the various species of metals are vulgarly constituted. Whether these be rightly so called is a useless dispute, and does not greatly help or hinder the affair of the Alchemists.

They bid us seek this material in the cradles of the more perfect metals; and since nothing can be hoped for among the perfect metals from compact gold, we must look to silver, or to something akin to it, as innumerable passages of the authors intimate, from which a whole volume might be filled. I will give a handful of these, as it were, by way of sample.

In the chapters ascribed to Hermes, the Stone itself is made to speak thus: “The Moon is my own, and my light surpasses every light.” Arnoldus, in the Semita of Hermes, explains it thus: “His father is the Sun, his mother the Moon.” By the Sun we understand gold, by the Moon silver. And he adds: “Now therefore I have sufficiently demonstrated to you …”

The Rosarium Majus: “Our Magnesia is the full Moon, the Mercurius of the Philosophers, that is, the matter in which the Mercurius of the Philosophers is contained. And it is that which Nature has gradually worked, and formed into a metallic form: yet left imperfect.”

An anonymous author: “It is necessary that the Sun should have a receptacle suitable and consonant for its seed and its tincture, and this is the Moon, that is, silver.”

Sendivogius (or rather Setonius) in Treatise XI calls it the menstruum from the Sphere of the Moon, which can calcine the Sun.

The Scala Philosophorum: “Aid therefore the solution by the Moon, and the coagulation by the Sun.”

The Turba repeatedly calls it the Spirit of the Moon.

But who can enumerate all? We see hence in what direction they point the finger. This material they call fire, water, vinegar which works upon the perfect metals in such a way as fire upon inflammable bodies, water upon salts and ice, vinegar upon bodies which can be dissolved by it.

One would need to search the mines, whether such a thing might be found in them; for in the writers on metals there is little wisdom here to be had. They describe not a few species of immature or formless silver; but who has ever seen or examined them? At times it appears in the form of a sluggish liquid, which afterwards coagulates into the best silver. A memorable history of this is related by Albinus, Berg-Chronicon, p. 110, which perhaps it will not be unpleasing to insert here in the author’s very words:

In the Count of Hohenstein’s mines in the Harz, especially on Enders-Berg, at the most famous shaft called Samson, this memorable and unheard-of thing happened: that there was found a white liquid silver, resembling quicksilver, which flowed out of the vein and outside, so that it could be gathered with the hands, and as soon as it came into the fire, from that moment it became true silver, as I have been told by trustworthy people. Some say the ore was like buttermilk; but as soon as it was held in the air for a while, or even preserved in vessels in which it was thought it could be kept soft, it hardened like sand or grit, and its white color turned to brown or sooty.

So much for this wonderful material, nearly answering to what Matthesius relates of his Gur, though it did not yet approach the nature of pure silver. The same Albinus, p. 127 of the same book, adduces notable things concerning different kinds of silver ore, which I prefer to leave for reading in that place, lest I fill my pages with too many testimonies.

Perhaps also worthy of contemplation are the things which Nieremberg, Historia Naturalis lib. 16, cap. 19, reports of a certain singular metal used for the solution of silver: Quicksilver, he says, was known only to the barbarians, but was of no use; for in place of it, for the benefit of silver, another metal was substituted, found in another lower hill lying near the mount of Potosi. The Indians call it huayna Potochi, that is: “the youth of Potosi.” Here was found a certain baser metal, almost lead, mixed with silver, which was used in place of mercury. They call it Zuruckhe, which means “that which causes to slip away,” because by its inflation the silver was made fluid, and not burned.

These are the traces we find in the writings of the Chemists concerning the first principle of metals, Mercurius, which, however, they cover so carefully that none may penetrate too deeply into their mysteries. Nothing indeed do they hide more studiously than this matter, on which the whole business of alchemy depends.

Their second principle is Sulphur: a spirituous, penetrating thing, coagulating metallic matter, the sources of which they do not dissemble. They wish, however, that it be drawn from gold, but through its material vehicle; for they despise the sulphurs of the other metals, as impure.

Some deduce its first origin from the Sun and the stars, but all that is uncertain. Others from subterranean fires which is not altogether absurd. For since the earth is a compound of all the first natures that are necessary for the generation of mixed bodies, there must necessarily be within it a great force of fire, without which nothing can be generated or mingled.

It must needs have for its familiars oily natures of various kinds, with which it is first mingled, whence to the outward parts oily vapors, now purer, are driven forth, more or less well cooked. These, mingled with water or earth, seem to produce various species.

And these are not only those commonly known to us sulphur, bitumen, and the like but many more, unknown to us, to which fire is especially familiar, and which spontaneously strive toward mutual mixture, so that they cannot be separated.

For combustion of oily things seems to be nothing else than the separation of fire from those matters in which it dwells. Therefore, since the Sulphur of the Chemists is truly an oleaginous substance, yet incombustible, and yet (as they say) fire embodied, or the nature of fire, it is most probable that it descends from such a first mixture.

Hamelius, De Fossilibus, lib. 2, cap. 9, p. 246, thinks that this sulphur is not to be deduced from the stars nor from central fire. To him its nature seems the same as that of vulgar sulphur, except that by long alteration it becomes fixed, pure, and incorruptible. A judgment not to be wholly despised.

For I remember reading in the writings of the Chemists, and unless I am mistaken, in the Correctorium of Richardus Anglicus, that within the nature of common sulphur there lies hidden that incombustible sulphur, and that it can be restored to gold whose sulphur has been extracted, as if from its own entrails.

This recalls to me a story, which I read in a certain manuscript book written in German, concerning gold extracted by the help of common sulphur and copper, or rather matured in copper; which I will insert entire here:

Gregorius Eusebius von Madrit told me that a certain Chemist came to Montanus and begged a small opportunity to labor, which was granted him. Then the operator took a hundredweight of copper, and kept it always in flux, and continually added sulphur, and thus wanted to bring the copper to ripeness. At length the neighbors complained of the stench, and Montanus dismissed him. But he greatly lamented that he had not been able to complete it. After some time Montanus broke open the furnace in which he had worked, and found a pool of ten ounces of gold sticking in the hearth, which had run down through a crack. Montanus wrote to him in vain, but he himself restored it to the Prince of Anhalt.

The faith of this story I leave in the middle; nor indeed do I advise anyone to spend money on an uncertain matter. Yet I was unwilling to omit it, since it illustrates our subject.

As for the parts of metals, which the Chemists so distinguish, no doubt seems now to remain. For what some thought that the substance of gold consists of similar parts is false, since its Sulphur, or tincture, can be separated from it.

In the baser metals, especially copper, this can be done, as many experiments have shown.

Hamelius, De Fossilibus, lib. 2, cap. 7, bears witness to the same concerning gems. There are some who, taking gems of lesser note such as amethyst, sapphire, chrysolite place them, laid upon an iron plate, with quicklime or steel filings, and cover them with live coals, so that by heat gradually increased they are stripped of their native colors, and put on the appearance of diamond. For if hardness and clarity be present in the stone, it will hardly differ from diamond.

If this should succeed, we would have a great secret of confecting nobler from ignobler gems. Yet the colors of artificial stones are sometimes washed away by corrosive liquids. In the vegetable order the same can be done. What dyes more than saffron? And yet from saffron its whole color can be so separated as I know, taught by a most noble man that I can present under a crystalline liquid of perfect transparency all saffron’s odor and taste, yet with no appearance of saffron; though the viewer sees nothing like saffron, the taster perceives pure saffron, or its most subtle essence.

This much astonished those to whom I showed that liquid, which is also used in medicine with great success. From gold too, though more tenaciously it clings there, sulphur or tincture called also the soul of gold can be separated, as both ancient and recent Chemists attest; which is confirmed also by Franciscus Luna, in that place of his book which we cited above.

And it is done thus: As much weight as the gold had from which the tincture is extracted, so much silver, if the tincture be cast upon it, will it tinge with its color and convert into gold itself. When this is done, a pale mass of gold remains, equally ponderous as before, to which its color can be restored by cementing. Something similar concerning such tincture of gold cast upon argentum vivum was publicly reported at Venice, by the learned Italian Alexander Tassonus, in a book written in his native tongue, entitled Pensieri diversi, lib. 10, cap. 26. I will insert his very words:

Among the most curious properties of Alchemy, none equals that of the examination of gold, whereby a great mass of it is reduced to a very small powder of purplish color, which by some is called the Stone of the Philosophers. Cast into a quantity of Mercury, made to boil over a gentle fire, it converts as much of it into gold as corresponds to the original weight (namely of the golden mass whence the powder was extracted). Whatever quantity of Mercury exceeds that measure, it fixes into silver. This experiment was publicly shown in Venice a few years ago.

So much this author concerning that tincture of gold, which, by his own judgment, he calls the Philosophers’ Stone. But the two differ as widely as heaven itself.

Nevertheless, he testifies that the thing was publicly done in Venice. And many believe that the Republic of Venice holds such an arcanum, which they say was communicated to its Senate by Johannes Augustus Pantheus, a Venetian priest, who also wrote a certain most obscure book on an art which by a barbarous name he called Voarchadumia, wholly different from Alchemy, and dedicated it to the Doge of Venice. It is found in the second volume of the Theatrum Chemicum.

The more sagacious have conjectured from this that no foreign gold or silver coin has legal tender there, but must be exchanged for other money; and since they have no mines of gold, yet the Venetians strike golden coin, which in color exceeds by a certain degree all native gold, however fine. Perhaps to this also may be referred what Matthesius records in Sarepta conc. 11, concerning the Venetians that they yearly fetch much red sulphur from Carinthia, to use in tincturing. But nothing certain can be pronounced here, for all is conjecture.

Most memorable of all is the story of sulphur aurum extractum, which, together with the judgment of Robert Boyle from his Physiological Essays, Essay 2, On Experiments which do not succeed, I will now adduce.

He relates: The matter was seriously told me by D. D. K., a man most alien from all habit of falsehood, if any ever was. He affirmed to me that, having left his laboratory in Batavia to a friend when he went abroad, and having left there certain kinds of Aqua Fortis prepared for his scarlet tincture, that friend shortly after his departure wrote to him, that in digesting gold in one of those Aqua Fortis, he had drawn forth a tincture, or yellow sulphur, from it, rendered volatile, the remaining substance of the metal tending toward saltness; and with this golden tincture he had transmuted silver, not without profit, into the most perfect gold. Hearing this, D. D. K. immediately returned to his laboratory, and with the same Aqua Fortis himself several times obtained the volatile tincture of gold, which likewise converted silver into true gold. And when I asked him whether the tincture itself could transmute into gold a quantity of silver equal in weight to that of the gold from which it was extracted, he confessed that from one ounce of gold he obtained only one ounce of sulphur or tincture, which was sufficient to turn a corresponding ounce of silver into the noblest metal.

And this (adds Boyle) I am the more inclined to believe, both because it is more certain to me from some experiments, than that it should be doubted, that the yellow substance or tincture can be separated from gold; and also because silver contains within itself a certain sulphur, which by maturation may become gold. Hence it seems probable to me what some most skilled in the metallic art, and attesting on the faith of their own observations, have said: that sometimes by the help of dissolving liquors (which also Francis Bacon somewhere noted), sometimes by the benefit of common sulphur (well roasted and combined with suitable salts), certain grains of most pure gold have been extracted from silver.

However, our Doctor’s conceived hopes of riches from this experiment utterly deceived him: for shortly afterward, when he repeated the operation, it again mocked him; the blame he cast upon the aqua fortis, and so determined to attempt the work anew.

But since all his efforts have hitherto come to nothing, it seems probable that the error arose from some latent cause: for we know such accidents have happened to others, without remedy of any kind.