Hermes the Curious, or New Physico-Chemical Inventions and Experiments of Christian Adolph Balduin

Buy me CoffeeHERMES

THE CURIOUS,

or,

NEW PHYSICO-CHEMICAL

INVENTIONS AND EXPERIMENTS

of

CHRISTIAN ADOLPH BALDWIN,

Fellow of the Academy of the Curious about Nature of the Holy Roman Empire,

and of the Royal Society of England,

(of the College of Hermes).

NUREMBERG,

IN THE YEAR 1683.

Translated from the book:

Hermes curiosus, sive inventa et experimenta physico-chymica nova Christiani Adolphi Balduini

To the blessed shades of

CHRISTIAN ADOLPH BALDUIN,

of the College of Hermes.

May deep peace make you blessed, now departed from this age

so lately the shining jewel of our choir!

Yet that we do not allow you wholly to rest this deed,

I think, is with your goodwill and not without praise:

lest your excellent discoveries, being posthumous, should perish, but rather be made known,

and a greater honor of your name now stand forth.

For what comes last is often most welcome, just as

the song is which the dying swan brings forth.

Therefore, after your death not at the gloomy crossroads of the world,

but to be read abundantly in these pages do you live on, though you have died.

HELIANTHUS.

TO THE CANDID READER

greetings.

The Imperial Academy of the Curious about Nature chose for itself the device: NUNQUAM OTIOSUS (“Never idle”); the Royal Society of England, the motto: NULLIUS IN VERBA (“On the word of no one”). The authority of both has always been very great with me, and I have diligently acted accordingly. For, since I was a member of each, I certainly did not pass my hours in idleness, so as to do nothing at all. As witnesses to this I bring forward what you are reading curious Inventions and Experiments.

And whereas I have allowed myself to be bound by no one’s opinions, and to swear to no Master’s words, the things contained here can easily acquit me of that.

Almost everything here is new. For, in Quintilian’s judgment, it is the mark of a sluggard to rest content with the things that come from other men’s talent and industry. They are short pieces, but in the matter itself they contain not a few things.

It remained that, having sketched out a “Curious of Nature,” I should now renew the work itself. In order that this might be done more quickly, the thought occurred to me of a little press, which at a low cost I might assign to my own portable uses. Nor will it lack success. For I bring forth these new observations, written and printed by our own hands, with a light screw-press, and without the other instruments that heavier printers commonly employ.

Read, then, I beg you, these first curiosities, Curious Reader; and do not pass judgment before you have understood them.

And do you, HERMES THE CURIOUS, continue by your favor especially to add spurs toward higher things. Farewell.

1.

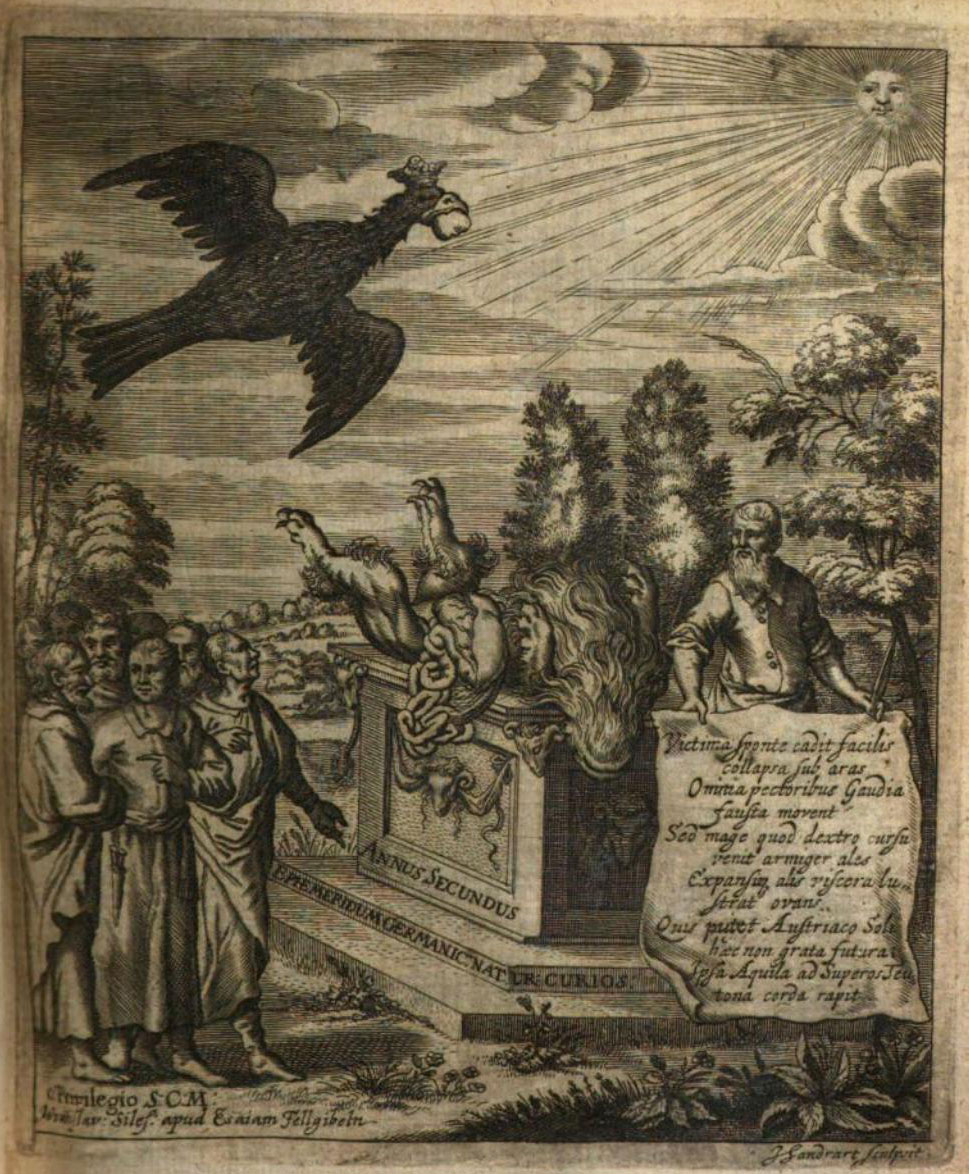

THE MAGNETIC SOLAR EAGLE.

At last I yielded to the requests of the very grave gentlemen of the College of our Imperial Academy. They kept urging me not to suppress even a brief description of that Magnetic Solar Eagle which at the nod of His Sacred Imperial Majesty I had made for everlasting memory at the most magnificent nuptials of the Most Invincible Emperor and his Augusta, celebrated at Passau on 14 December 1676, nor to begrudge it longer to the public. Let this, then, be the first of the Observations which, concerning my physico-chemical inventions, with God’s help, I have resolved to publish, one each month.

It represented the Imperial form of the Eagle two-headed and marked with a crown. The Sun shone upon its breast, with these two letters, L & M, bound together, notable and conspicuous as the indicators of the names of Their Most August Imperial Majesties, LEOPOLD and MAGDALENA. It bore two other letters, as if set into the beaks, E & T, by which Eleonora and Theresia, the remaining august names, were designated. Its talons were armed with a scepter and a sword. The sky round about it was set with golden stars. The mirror in which this effigy appeared was an octagon fashioned by chemical art. On the gilded silver case were engraved these verses:

The eagle, glittering with the flame-spewing Sun, draws gold;

and the Sun of the Empire draws thee, Leopold.

Accordingly, just as by the name Eagle I would have the Emperor himself understood, and by the Sun the Augusta, so at whatever time of day by a magnetic power the Eagle drew the fire of the Sun from the air (without scorching), and by its operation the whole [mirror] appeared in the dark as if all aflame.

Lest anyone think I am saying this gratis, I have witnesses everywhere he who by his own letters reported to me that His Sacred Imperial Majesty had not seldom made trial of the thing, and had ordered it to be placed in his Treasury, so that there (in the words of the most eminent Nicolaus Guilielmus Beckers, Imperial Councillor and Arch-Physician) it might abide among the Imperial rarities and the author’s fame might shine forever.

And what more? That Eagle was long ago not merely a Caesarean Phosphorus, but, illumining my home with its golden rays, was like a little sun. Besides, while we were preparing a Universal Subject of the Sages in which lies a real and essential spark of the nature of Fire and Light, indeed the most secret (nay, immortal) soul of the thing itself, its Azoth and consequently an inward, invisible fire that produces a visible solar fire in marvellous fashion: its splendour and shining interchangeably darting forth rays no light is equal to it in rarity except that which is of the same stock as fire; and the heavenly fire, by a purity altogether its own, is distinguished from the elementary.

A great thing it is truly to know Light; if you know it, you will know true gold and the Philosophers’ [gold], you will know Fire and many other things that the artifice of men has long concealed.

But light rarely flashes forth without the favour of heaven, or without labour does it appear, even though one be occupied in the brightest light. Therefore let the eternal Light illumine our darkness, and may we see more clearly that open Light which has disclosed the Infinite Light!

2.

THE IMPERIAL FLASHING APPLE (ORB).

It had been little (as I had very graciously written to the renowned Academy of the Curious about Nature in our paternal letters, what they call their patents) unless the same letters had borne the names [of the witnesses], that His Sacred Imperial Majesty, exercising his accustomed munificence equally toward me, might now that a year has elapsed reward me with a most splendid golden torc, together with a Caesarean effigy, above all. To whom never, at any celebration, for giving thanks at a celebration much less to repay them I could not do enough; therefore I judged that it befitted my most devoted gratitude, in turn, to dedicate most humbly to His Most Sacred Majesty, and to present, that which I had prepared by chemical art, the Imperial Flashing Apple. It was a huge glass globe, hollow, marked with a cross, and finally entirely gilded save that around it there was inscribed the most august name

LEOPOLD

which shone through by emitting the fire that was contained within. For if you set the globe in the dark, it kept flashing continually through the letters of the name LEOPOLD, as if flames were bursting forth. Nor did it do this only once or twice by day, but whenever it was looked at even by night.

Furthermore, this fire exists in a liquid form; hence you may rightly call it either Fire-Water or Water-Fire.

The material comes from my very own body, out of which by a singular chemical art, though not without great labor that moist fire was prepared; it differs greatly from the dry fire to which our Magnetic Solar Eagle owes its origin.

For it is composed out of the Salt, Sulphur, and Mercury of the Universal Subject of the macrocosm; while from the same principles it is the subject of the particular microcosm. Yet both are free from corruption and without burning, such as the Arab philosophers once exhibited in the renowned city of Aden to the Sultan, a most great and many-sided prince (as beyond doubt is attested by the most excellent Puerarius, Professor of Philosophy and Doctor of Medicine in the Genoese Academy, a man illustrious in learning and lineage; Caspar Scioppius).

Accordingly, just as Nature has also granted in our age to find new fiery things, so the Light innate in all things as though pyric is shaken out by our labors and called forth from its hiding places; and from a small spark an immense flame is kindled, suited to the constitution of the heavens, raises us up, and urges us to strive higher and for the Highest, that we may be restored to our Origin, as if by a torch set beneath.

Meanwhile since this Imperial Flashing Apple will, without any doubt, bring very great delight to His Most Sacred Majesty so may it be that the Imperial Orb (whose device is the same “apple”), together with the most great LEOPOLD, not only shine in peace and cherish with kindness and protect all his faithful subjects, but also flash forth especially in war, and everywhere strike terror into foreign enemies this I sincerely pray and beseech.

3.

THE FIERY VERTUMNUS.

As it is rare for anyone to think well of an enemy, so, while the fires of that most grievous war begun last year by the King of the French against the Roman Emperor were raging everywhere, this was often the rash French wish:

“Let the lily flourish; let the eagle perish!”

I, who was then busied with fiery inventions, seeing this, began to think about a Fiery Vertumnus not that I might invert that wish (which I could quite easily understand), nor (far be it from me) repay like with like, but rather that I might also here indulge my curiosity.

So I fashioned upon a great half-round copper plate, from a certain special mineral substance as well, the emblem of France, a lily; and I arranged it in such a way that within it the two-headed Eagle was scarcely discernible, with the motto: Lilium floreat, Aquila pereat! (“Let the lily flourish, let the eagle perish!”)

But when the plate had grown a little warm, and I immediately carried it into some dark chamber, straightway that very design with the motto of the Lily changed into the Imperial Eagle, and displayed this inscription instead: Vivat Aquila! (“Long live the Eagle!”), belching forth so much flame or fire without smoke or stench as would be enough even for a man standing close by and peering within; while the lily, contrary to the French wish, would again and rightly be in good case, if it were brought out of the dark. Whenever one pleases, these things may be tried.

Now, since peace has not long ago been restored by divine clemency and the wars put to flight, and since the order of affairs seems reversed, this my Vertumnus has learned to walk forth in another garb: the Eagle in the Lily, and likewise by this amicable law of composition as if they were wedded and made one with each other, each of them pouring forth the light of Peace whenever one wishes; nor without a Sincere Wish, which is rather to be read thus:

LET THE EAGLE LIVE,

LET THE LILY FLOURISH!

Behold a true Fiery Vertumnus! The subject from which its matrix is made is mineral, adhering to metallic stones; nor is it of one single kind. It is produced very various in colour now white, now green, now purple. By the working chiefly of this material you can display fiery images or emblems in place of various colours, with flames of different sorts, to the incredible delight of eyes and minds.

For in this matrix there lies hidden a mineral fire, the first mover of metals, or embryonic sulphur, so pure and so subtle that, if you throw it upon burning gunpowder, it does not even ignite it. And when a little of this material, somewhat calcined, is put into a hermetically sealed vial (set upon warm ashes), it can easily burn and shine for a whole day without smoke a thing likewise worthy of admiration.

Since therefore it is good for speculation, and practice and nature agree with it, I have examined this ore with all diligence; and having spent several books upon it, I began about forty experiments of these. If the work shall seem of sufficient value, it may come to pass that these experiments themselves may someday see the light. Nor do I in any way doubt that many other miracles of nature lie in this subject and may be brought to light by equal study.

4.

A LITTLE GLASS SPHERE (set in a mouth), SHINING

There appears in the Philosophical Transactions of our most illustrious Royal Society of England, dated 18 Jan. 1666, no. 21, report 4, “On the complete method of preparing the shining Bolognese Stone,” the following remarks, worthy of note: There is not in the nature of things any material known to us that has the virtue foretold of this stone; so that (for the people of this age to come) it is hardly likely that this phenomenon will be found again anywhere except in books, unless perchance some happy genius should hit upon the same, or a similar, science.

When I had turned these matters over in my mind for a long time and often, I confess a desire seized me to rescue that art from perishing, and to preserve among Arcana the light-bearing stone which I had prepared; and also to reflect upon other subjects which, if discovered by me, would far surpass in power that shining Bolognese stone I mentioned. And indeed I seem to myself to have accomplished this in my Solar Eagle, in the Imperial Flashing Apple, and finally in the Fiery Vertumnus. Yet not content with these, I went on to this further thought and inquiry: might there not also in human hearts be some visible fire or light that could be drawn forth by a luminary magnet of some kind? And, if granted, would it be so powerful as to stir up and ignite the latent fire in the magnet itself?

As to the first point, I already knew from the Dissertation on the Little Flame of the Heart by Jacob Holstius, a most excellent man and its author, what it might be: namely, that it is a fire of the purest Flame of the Heart, and yet does not burn. Although the most noble Walter Needham, Doctor of Medicine at London, in his Anatomical Disquisition on the Formed Foetus, calls the so-called vital little flame a succenturiate [accessory] one; and the illustrious Robert Boyle has touched on this matter as far as he deemed sufficient, though without, no doubt, an ocular demonstration. Concerning the second [point, i.e., the magnet/light], as to the second point, I thought there was less need to labour at it, since I was assured of a magnetic fire from our solar or philosophical magnet. By its benefit, therefore, not long ago I chemically prepared a little glass sphere, which could be neatly held up by a gilded small stem.

If you set it to the mouth and warm it a little there, it shines in the dark so much that you would think it some red-hot little ball of iron. It suffers no decay unless you break it; and try it whenever you please, it will never fail.

Indeed, hung from a woman’s neck, I judge it will constantly lie between the breasts and shine secretly, so long as life remains to her, because of the warmth that they breathe.

For the most noble spiritual and celestial content is in the same little sphere of fire, which you would take for the Soul of the world. It is most closely akin to innate heat, or to the spirit of life of those bodies which surround us human beings. Nor will innate heat have any chamber other than that heavenly Light which, at the creation of the Universe, God dispersed through all the elements and the heavens, having set its tabernacle in the Sun; since, conversely, the human soul is a certain Divine Light, and this is rightly believed.

5.

THE ARTIFICIAL SUN, PERPETUALLY MOVING.

Let no lover of curiosities be ignorant of this: a perpetual artificial motion has hitherto been the true torment of engineers. Hence many, after the lapse of so many centuries, have reckoned a machine of this kind among impossibilities.

Therefore, since in our affair the principle of infinite motion is lacking something intrinsic to the art helps must be sought from Nature herself, by which an equivalent kind of permanence of motion may be had; and, by Art duly applied to the machine, it may produce a perennial mixed motion, that is, physico-mechanical.

Relying on this principle, after much trial and sweat, I at length discovered a SUN that is perpetually in motion.

It bears a human face, sending out rays all around. Its material is a thin plate, likewise gilded. A path through the air is painted in the “sky” [the background], which, to one looking down on the picture, affords a cleverly painted region, about two cubits long (and more), along which it runs.

This “Sun,” as I have said, shows by its course, through changes in the air’s temperature, the increases and decreases of heat and of cold not only in the nearest surrounding air but also in the air far and wide around indicating at the same time which day in the whole year’s course is the hottest and which the coldest.

Yet, lest anyone suppose otherwise, this Sun is not animated like an automaton. What governs it is an aerial Hermetic magnet, likewise set in equilibrium; and it is subject to no decay from either heat or cold. Even in winter when we are in the season opposite to summer no vapors familiar to us hinder it (or, if its operation be concerned, nothing hinders its course) by means of that heat with which, at that season, we defend ourselves from the cold; whence one may even judge of the weather without a hypocaust.

It is now four years since I bestowed this Sun upon its “sky,” and it has not yet slackened in its effect.

This perpetually moving device I exhibit in our Museum, not without the astonishment of the neighbors, to the eyes of the Curious who have not yet sufficiently penetrated by what magnet, and according to what degrees of heat and cold, it happens to be moved.

Since it owes its origin partly to a discovery of Chemistry, and partly to that of Physics and of our Mechanics, who does not see with me that in like manner there is occasion to produce not a few other perpetual machines?

Let me mention, for example, the twelve signs of the Zodiac: these could be fashioned as elegantly as possible and applied to the painted sky in their places, so that each would appear in turn with its proper risings and settings. And since, with the astrologers agreeing, some signs are fiery, dry, and hot, and others, on the contrary, cold (together with the watery ones and those and likewise I would contrive it so that, in turn, by its appearance it would indicate every degree of either heat or cold in the airy region throughout the whole year.

So great is the thirst of human minds their desire for the things that delight them is so greedy that it can never be checked, nor even then satisfied, when something new is always being looked for!

6.

HERMETIC “ENCAUSTIC” (INK).

It is reported that, under the rule of Tiberius, a certain craftsman discovered a material that was ductile and malleable, and presented it to Caesar as a gift though to his own irreparable harm; for the Emperor ordered him to be beheaded, adding the reason that, if the art were to become known, gold and silver would be cheapened, as it were, to the level of glass. This story is related by John of Salisbury, that Englishman who flourished about the year of Christ 1182, in the Policraticus (book 4, chap. 5), and by Pliny (book 36, chap. 26) among matters uncertain and bordering rather on fiction; yet Dio Cassius (Hist. book 57, p. 614) does not by any means take all credit from it. See also Isidore (book 16, chap. 15); Jan Dousa in his notes on Petronius (Praecid. chap. 9); Ludovicus Coelius Rhodiginus (book 20, Lectiones antiquae, chap. 30); Guido Panciroli, Rerum memorabilium deperditarum, part 1, title 36. But that Caesar Tiberius had the man beheaded although who does not know from Suetonius the cruelty of his nature? is this, therefore, a reason to call the art itself into doubt? On the side of those historians, in matters where we believe many other things, I think it is not unfair to include this as well, whose age is now lost, as Panciroli, whom I have already mentioned, not undeservedly records.

Meanwhile, not so very long ago I found a liquid, which I call Hermetic Encaustic; whose power and efficacy are so great that it can penetrate even the hardest glass.

Among the Ancients there was a kind of painting called encaustic; afterward there was the liquid with which the Caesars wrote, namely made from the blood of the murex, that is, purple dye (see the various rescripts on the subject), and it was used for designation. But since encaustum has come in our day to mean the ink which we too who write use, I gave my liquid that name yet with an addition: I wished it to be called Hermetic, not from my own by-name “Hermes” only, but chiefly from the material out of which it is made, namely a Hermetic (i.e., mercurial) matter.

With this I am accustomed on glass tablets to impress types and to form images, landscapes, and insignia; also to write mottos, in such a way that as I am wont to do upon the “sky” [i.e., a glass back-ground] those figures are not, as it were, engraved into the glass, but appear as if cut out and standing forth in relief. Of this I have hitherto shown many proofs especially this most elegant one, produced upon the mirror-glass of the most powerful King CHARLES II of Great Britain, founder and patron of our English Society, exhibiting not long ago his name under the royal crown.

It is certainly no mere nothing nor a miracle, but should be ascribed to Nature, that she has given us a material by which even the hardest glass [usually penetrable by no other strong waters or corrosive liquors] can be softened.

Moreover, from the same principle I lately made for myself a white mirror-glass; and upon a leaf there was fashioned a certain parrot (so to speak, a figure “out of a leaf upon a leaf”). It was transparent like crystal, while the glass itself was dark, of the color such as the murrhine cups. Since the glass is not liable to corrosion either by alkaline salt or by any corrosive spirit, it is not to be wondered at if, when immersed in common water, it becomes pellucid; and, on the contrary, when dried, it returns to its former obscurity.

7.

THE PERPETUAL HERMETIC PHOSPHORUS.

And although what I published about Phosphorus some four years ago would seem sufficient so that for the future I should say nothing more on the matter they thought I should say no more; yet because in an Epistolary Commentary on Phosphorus the Most Excellent GEORG CASPAR KIRCHMAJER, Professor at Wittenberg an old friend, bound to us by the loyalty of that friendship seemed, among other things, to be trying to dim its splendour, favouring Kunckel more; I could not help, though unwilling, but disperse the mists which he was casting before men’s eyes yet doing so kindly and courteously, as our Academic Law XII enjoins.

Nor shall I here discuss at length the invention of Phosphorus which the most distinguished gentleman described for us [as customarily made from inspissated human urine]: whether that discovery should be ascribed to Kunckel, or rather to Brandt, the Hamburg chemist I will not now examine; far less will I inquire which phosphorus excels the other. What I take up if only for a little in examining and refuting is the things most learnedly set down by Kirchmajer; adding this one point meanwhile, that my invention in particular has something more of phosphorus in it; and I shall turn aside modestly, gently, and without gall, to show the world of letters that its powers are not yet weakened, despite his dissent.

For when (Commentary, p. 9) he says that my phosphorus has no light of its own, but only a borrowed light in itself, I would very much like to know what he dares to prove. Perhaps against what he contradicts he is ignorant of the method of handling phosphorus. And surely he has not read those words in the Appendix [to my treatise On Aurum Aurae], §9, which are these: that phosphorus, or the magnet of lights, rejoices not only in a foreign light, but shines with its own fire (or, if you prefer, with its own light). But perhaps, because he has not seen it, the worthy Commentator does not credit the assertion. I will not force him.

Meanwhile I promise and stand ready at whatever time to give a prepared demonstration to anyone who wishes, showing each particular point: that my phosphorus, which I have already called so often that phosphorus, if you touch it even lightly with a feather or a straw, without any prior attraction of light, emits certain sparks. Thus it is with good right that I call it phosphorus, since it possesses not only a true substantial light within, but also attracts external light.

Next, as though (p. 10) he had somewhat inaccurately charged it with lack of durability. But what if I reply with what the most renowned author of the Commentary himself suggests in that same work (p. 6): “Is Alkor not seen full with the Moon?” They report that the very specimen which, set like a star and enclosed in a little silver case plated with gold, I presented four years ago to the Most August King of Great Britain, still retains its full powers, i.e. it still shines. And what of this that I can still easily produce several phosphori, among them some that I made five years ago, kept only in wooden containers, which likewise have abated nothing of their effect? I do not deny that the cause of their long duration lies by no means in phosphorus alone, but also in the care with which it is prepared. If, without doubt, the worthy Commentator does not know the method, what wonder if he takes away credit from mine? But why does he attack, in ignorance, what he does not grasp?

Finally he asks (p. 10) to what use the Hermetic Phosphorus is suited, and goes on: “I will pledge my public faith that in nitre (the material of phosphorus) these arcana (to wit, the Alkahest, etc.) are neither to be found nor to be hoped for.” I answer: I should not believe that he himself really wished to say this. Meanwhile I can very readily be persuaded of this much that he has not yet truly examined the nature of nitre. But suppose he denies that marvels lie hidden in nitre, from which they may be elicited what then? Well then, if these things be true, I, for my part, will do the Commentator and the rest of the Curious this favour: to show, by the experiments that follow, what chemical arcana I have discovered in the matter of phosphorus chiefly in philosophical nitre. Yet so as not rashly to violate the seal of Hermes, nor be found offending or doing wrong against that same Our Father.

8.

THE EVER-LIVING PYGMY.

There is indeed an experiment with quicksilver, suspended upright within a glass tube, for the demonstration of a vacuum most memorable and exceedingly delightful. Which, as Valerianus Magnus the Capuchin relates; and many maintain it so. Thus most writers Roberval, for example, and Kircher, Mersenne, and Schott acknowledge the famous Tuscan mathematician Evangelista Torricelli as the true author. George Sinclair, Professor of Philosophy in the University of Glasgow, gives the invention the name Baroscope in his book On the New and Great Art of Gravity, where he treats these matters at greater length.

Now, as it is quite easy to add something to inventions already found, so the noble Otto von Guericke, with a certain singular practice some years ago, contrived a little figure of wood to ascend and descend within a glass tube, for detecting at any time the weight of the air. But since it is his special habit to keep things secret he has thus far begrudged the public the arcana, however clearly his great diligence shows how powerful they are.

Although in the method of preparation which I seem to myself to have devised I erred in nothing, it was only the dimension of the tube that stood in the way. Meanwhile the Most Illustrious N. N. of O. (i.e., a noble patron) supplied me with a certain diagram, with observations added. Yet when I too found not a few things needing correction here as well, I girded myself to the work; with this success that, following Torricelli’s principle, there arose for me not only one “Pygmy,” ever-living, but two others, springing from another principle of my own. Of these for the present:

(1) A spiritual kind, not uncomely in workmanship a little column. Upon it are set two crowns, as it were linked one to the other; between them a small glass tube projects, marked with distinct little gradations painted thereon, and, with elegant carving, it encloses the Pygmy. This tiny “little man,” wearing the appearance of life, is borne by the external air; and by continually changing place now ascending, now descending he points with a little finger what faces we are to expect, even two hundred miles round about in the neighboring lands: what rains, what gales, what other storms, and whether they are about to reach our horizon or not. Commonly he gives the sign two or three days beforehand; for as he uses speed or delays, so things turn out. Here certain rules are applicable, which furnish certain rules for judging the weather to come. And if you wish to know upon which region within 200 miles the winds and heavy storms are pressing, get yourself an instrument on which the thirty-two points of the winds are inscribed, and set it so that it answers exactly to the situation of the four quarters of the world.

(2) After this there are no longer only three, for from quite another and a physical foundation I have enclosed a Hygroscopic Pygmy in the hollow of a glass sphere. This is seen to be divided into several equal parts, with their numbers marked outside. The little “man” itself, fitted into the machine small indeed, but less obvious to those who encounter it turns round under the pull of an ethereal magnetism, now toward the East, now toward the West, and then toward the other quarters of the world, indicating by what it observes how cleverly the state of the air is shown; by which one judges the degrees of moisture and of dryness, and what weather of the sky will follow on the next day or night, etc.

(3) It is now two years since we also found a Time-measuring Pygmy. Its principle is automatic mathematics. Through a glass tube, which I made not more than two cubits long, it ascends every twenty-four hours, and with its finger points out on the tube the marked parts of those hours quarters, halves, and wholes by day and by night alike. A gilded globe covers this tube. The base, of very soft alabaster, is the skull of a piece of workmanship not to be despised. Under it are written in golden letters these verses:

Time, and the year, and age pass by with a silent step;

One lives by one’s wit: all else shall belong to death.

9.

THE HERMETIC MUMMY.

Whenever one thinks of the Egyptians and Romans and of the more civilized nations, the funeral anointing or embalming at once comes to mind: the rite, namely, by which those mortals used to keep putrefaction away from dead bodies, employing salt, nitre, cedar, asphalt, honey, wax, myrrh, balsam, and other things.

Although in our own age the care taken in the funerals of the great is not infrequent, yet it is not the same as among the Ancients, who first eviscerated the body. Because this could not be effected without dissecting the corpse, that procedure held by not a few to be cruel has plainly fallen out of use. Hence there arose the question whether by a better method it might be permitted to preserve corpses whole; and this the modern medical-chemists have especially and diligently pondered men who deserve to be named for honor’s sake: the most distinguished Nicol. Steno, the most illustrious Ludovicus de Bils, and the excellent Gabriel Clauderus.

Now just as their process acknowledges for its principle something mostly saline, on account, namely, of salt’s effective power of penetration, so those salted bodies are exposed in the highest degree to the changes of the air, and especially to moisture (which certainly liquefies and dissolves the salty substance); and they withstand putrefaction only for a time. (The most prolific Th. Bartholinus, in his Dissertation on the Liver, p. 551, reports not without some severity that the Bilsian method of embalming leaves bodies very damp.) Clauderus, an excellent man, Methodus Balsamandica, lib. 6, p. m. 172, freely confesses that his liquor (which he prepared from calcined bones and Armenian salt), when applied to corpses laid in little coffins, has not yet altogether prevented the damages of the air; yet he does not despair, given God and time.

Accordingly I too laid my hand to the work six years ago; nor was I silent, in my Aurum Aurae ch. 101, about a thermometer, which I had made perpetual by the help of a certain preserving salt of my own blood. To this there is added that, in chapter V of Veneris Aureae, I inserted an experiment of a certain Gorgonian or petrifying juice belonging to us and truly singular. Not content with these things, I went further, and added to the embalming a device for freeing the body from the injurious touch of moist air. For when, by the aid of a stone-making seed, Nature transforms not herbs only and wood and bread and eggs, and fish and birds, and finally skin and other things by a certain marvellous metamorphosis into stones, then indeed sometimes even infants in the mother’s womb themselves are found thus preserved the human form remaining, without any intermediate putrefaction or dissolution of the matter. (Of such a kind though of an adult size J. B. van Helmont, at Paris, records that a foetus, turned into stone, was cut out: De Lithiasi, Tract. 1, cap. 1, n. 11. Denys tells the history of an infant found in the abdomen and changed into a stony hardness; and likewise that petrified boy from a certain city of Africa who, many years ago, was sent to Cardinal Richelieu, as the most noble Th. Bartholin relates, Epist. Med. 53, Cent. I.) Why, then, should it not be possible by the craft of art with the help of that petrifying seed of which I spoke to communicate to corpses at least a durable hardness?

In the work itself, last year, I carried out what I had speculated; and I contrived by nitre purified from very white sand that my liquor should be petrifying, which, when sent into the microcosmic spirit, did not fail in the experiments that follow.

1. I separated my fresh blood from its phlegm, and added to the blood an equal quantity of the said liquor; the mixture succeeded so well that to this hour I keep the blood red excellently, and I am altogether free from fear of its putrefaction.

2. I took a fish (of the smallest kind which they call Fundulus).

3. Next, a piece of flesh; I seasoned each for the space of an hour with my brine; then dried them in the air; and, being dried, I keep them through the virtue of this balsam no doubt safe and entire for us in the future.

What more? 4) Shut up in glass, after a few days the very liquor itself solidifies in the air and congeals, not unlike ice in its right.

Although these things be so, they have not yet satisfied my desire not because of the labour (which I see is required partly in preparing the pickle, partly in embalming and drying bodies), but because I have also discovered that air, too, can be petrified by art, and at times can be resolved into sand and salt, and thus corrupted even though, with all the care you can, you keep off and shut out the air, so that it may not alter them. Hence, not long ago, we devised and discovered for ourselves another and wholly new method of embalming, which leaves what is called “pickling” many parasangs behind.

Among the Ancients the “mummy” of the chemists is often the balsam; and in this sense I too have called my new balsam a “mummy,” and Hermetic. For it is our universal salt together with a catholic balsam which, as I have found, is prepared with scarcely any labour or expense. And although, since it has been permitted me to penetrate this arcanum, I have been hindered by weightier affairs, and thus have confirmed it only by experiments on fish, mice, and other small animals, yet I am altogether without doubt that by our Hermetic Mummy larger bodies, even human, can likewise be preserved so that, with no entrails removed, no intestines taken out, nor even the brain separated, there will be no corruption to be feared from air, water, or earth.

On which matter it may happen that I treat at greater length elsewhere, or impart it to the Curious Reader in a separate treatise.

10.

AZOTH, OR THE HERMETIC SALT

The philosophers of every age have thought most nobly of common nitre, and have spoken of it likewise; for they called it the Magnesia of the Wise, and Titanian now Solar, Lunar, and even Ouranogaean [heavenly]. For it consists not only of the earthly salt (which is its magnet or attractive part), but also of the airy and fiery salt: compare them, and you will find as it were its iron and steel, that is, the thing attracted. You may recognize in it the Sun as the Father, and not improperly call the Moon the Mother: the red and igneous it has from the Father, Spirit; the white and cold from the Mother, which fitted it with a body. Whence it is both hot and cold, life-giving it is at once life-giving and deadly.

A wondrous offspring indeed of Parents so different in nature! Since I have examined it in various ways not only yesterday but today as well and have brought forth from it things which may with good reason be counted marvels, the first to occur among them are these: the Spirit of the World (which some, not wisely, think is drawn for us out of the air), the Balsam of the World, the Solar Eagle, the Hermetic Mummy, etc.; and, to speak so, at last the highest of its lower arcana the central, catholic, and pure mercurial nature of Nature where I found what lay hidden, and which I here call Azoth or Hermetic Salt; for the chemists use these names Azoth, Salt, and Philosophical Mercury indiscriminately and promiscuously.

Now the properties of this thing itself, which I now set down, are these:

1. It shows a whiteness like snow.

2. It tastes of nitre.

3. It dissolves whether in wine or spirit, and also in water; likewise in other corrosive menstruums when poured in without any hissing.

4. It melts on embossed silver if you set beneath it a lamp-flame or glowing coals, becoming like water; and if you remove the heat it freezes again, like snow. Take care, however, not to apply too strong a fire; for then Hermes’ little bird will desert its nest, and it will play the flying dragon, evaporating more quickly than you would think, until none is left.

5. It causes no annoyance by stench nor by any corrosion.

6. Our Azoth is not properly corrosive; it is rather igneous.

7. It is something incorruptible, by whose favor Nature preserves all things, acting as the supreme agent.

8. A true salamander living in the fire, and growing and multiplying there.

9. It bears within itself a most excellent medicine; I have thus far experienced its powers in more than a few diseases in malignant fevers, in the stone, in the hypochondriac malady, and other similar ailments.

10. And although this Hermetic Salt is a volatile body, yet it has its own hidden center, with the nature and disposition of the fixed and permanent; by long and continual coction it at length shows itself plainly and breaks forth.

11.

THE HERMETIC ALKAHEST.

All that is commonly reported about the Alkahest goes back to Helmont: so much so that anyone who hears the word straightway thinks that he possessed that liquor, the most penetrating searcher-out of Nature’s secrets; while some go so far as to doubt altogether whether there ever was or is that universal menstruum which we point out by this name. (Consult the Most Excellent Ludovicus de Comitibus, in the preface to the Disceptationes Practicae; and also the letter of Otto Tachenius, by which he made the question of the Alkahest a matter of public right.) But since that very celebrated man (Helmont), who in other arcana invented nothing lightly, not only repeated the name of the Alkahest many times throughout an entire work, but even described it (in the Arcana of Paracelsus, p. 441): that it is a liquor immortal and immutable, a circulating water-salt, which resolves every tangible body into a liquor that coheres with it, etc. surely the whole matter is not to be rejected out of hand, even if he strove with the greatest zeal to keep it hidden, and even wished the menstruum to be unknown to his own son Franciscus Mercurius.

Although I am fully persuaded that Helmont used quicksilver as the material in preparing the Alkahest, I do not at all think that quicksilver which I have called living cannot, by the help of artificial fire, be turned into a water that no fire can alter; namely, when you purge it of its superfluous parts of that accidental, outward, and combustible sulphur, and also of the superfluous moisture so that there remains only the inward fixed radical sulphur of the living silver. For if that serpent has bitten itself, then, revived now from its own poison, it can neither die nor be destroyed “Mercury from Mercury,” as they say.

And yet though I hold these matters most certain to myself because the work is so arduous and toilsome, and would require even the expense of much precious time, I have so far scrupled to involve myself in it. Rather did I think I ought to postpone taking it up, however highly others may value it, and not immediately, I saw it could be done; and from our Hermetic Salt which in some measure partakes of the properties of Mercury I could compose for myself a catholic solvent. For this Salt has sulphur together with itself, and it has mercury; and it is a pure, most pure fire of nature, not elementary but rather celestial, incorruptible, penetrating.

Nor, I confess, would success have failed our labour and such great expense. Our Alkahest dissolves vegetables, nay even coals; it dissolves minerals for example, it dissolves the stony part of cinnabar; it dissolves all metals, and indeed without corrosion, and reduces them to states such as are probable. For this dry water brings every body back into a more subtle substance, together with medicinal faculties.

Now the King of the metals comes before us for special examination a thing plainly singular in its institution with me. But of this in the following chapter.

12.

THE MEDICINAL HERMETIC STONE

Among other names it enjoys that of universal menstruum, and it is the Golden Magnet both because there is a notable sympathy of it with vulgar gold, and because it signifies that it can radically dissolve that metal and, as they think, unite itself to it with ease.

Accordingly, last year, to see whether that dissolvent the Tree of Hermes, or Fire of the Wise would burn Gold to ashes, I celebrated a philosophical marriage of our Alkahest with the purest gold. Thus, when I had mixed the lime of Sol with the Alkahest, and allowed it to digest gently in a vial, there followed no violent solution such as is wont to be produced by aqua fortis, aqua regia, or other liquids of that kind, but a soft and gentle one, with no bold hissing at all. And, after some weeks had intervened, the menstruum with the gold, being sublimed, began to assume various colours ashen, green, yellow, red, brown.

Again, after the space of a few months, you would have thought it ink-black. After this there followed a whitish hue because the Solvent, when the dissolved matter flows with heat like water, on the contrary congeals with cold. Now again some weeks go by, and it was seen to be of a yellow color, today inclining toward red. A spectacle than which I hardly remember ever to have seen anything more delightful or more wonderful!

Nor with the tending of fire by day and by night having wearied me for well-nigh a whole year shall I even now abandon the attempt, while I hope (God willing) soon to have a supply of the Medicinal Stone.

Meanwhile, since only a few things remain to bring this little work to completion, let there for the moment be a commanded pause to these matters.

The End.