Isaac Newton Manuscript: from Faber’s Hydrographum spagyricum and Palladium spagyricum

Buy me CoffeeIsaac Newton Manuscript: Ex Fabri hydrographo spagyrico

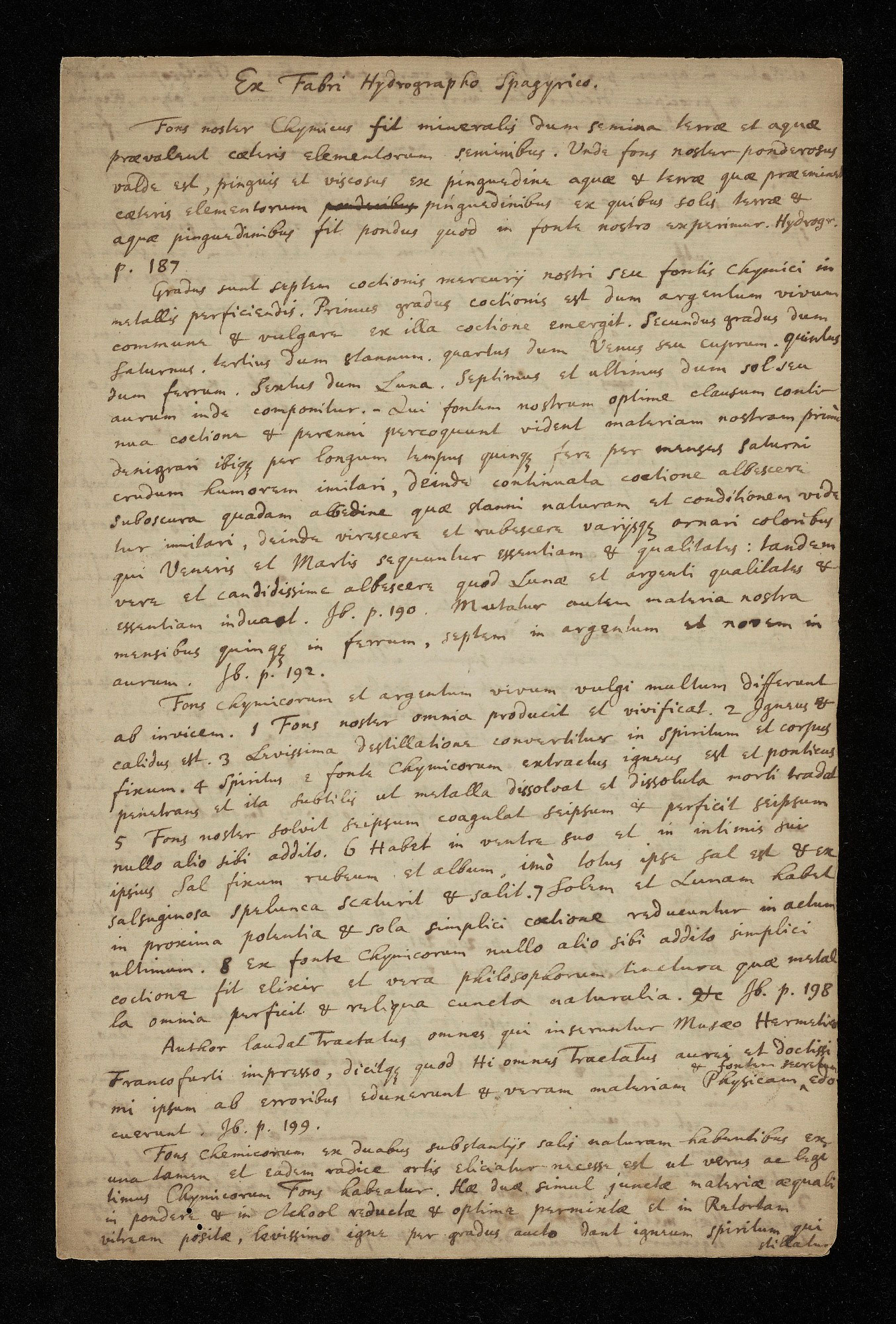

Isaac Newton penned these four pages of notes on the works of Pierre-Jean Fabre, a well-known 17th century French Paracelsian alchemist and physician. We know Newton owned a copy of Fabre’s Opera, published after Fabre’s death in Frankfurt in 1652, which contains the two works cited here: Hydrographum spagyricum (1639) and Palladium spagyricum (1624). Clearly written in Latin with citations to specific pages of the two books, this manuscript reveals which of Fabre’s passages were most important to Newton.

Isaac Newton penned these four pages of notes on the works of Pierre-Jean Fabre, a well-known 17th century French Paracelsian alchemist and physician.

BURNDY #13

MSS 1024 B

RB NMAH

Burndy Library

Chartered 1941

Gift of

BERN DIBNER

PAGE 1

From Faber’s Hydrographus Spagyricus.

Our Chymic Fountain becomes mineral when the seeds of earth and water prevail over the seeds of the other elements. Whence our Fountain is very heavy, fat, and viscous, by reason of the fatness of water and earth, which surpasses the fatnesses of the other elements [MS has a struck-through word [[pandeibus?]]]; and from the fatnesses of earth and water alone there arises the weight which we experience in our Fountain. (Hydrogr. p. 187.)

There are seven degrees of the cooking of our Mercury, that is, of the Chymic Fountain, in perfecting metals. The first degree of cooking is when common and vulgar quicksilver emerges from that cooking. The second degree, when Saturn [lead]; the third, when [[glannum]] [i.e. Jupiter/tin]; the fourth, when Venus, that is, copper; the fifth, when iron; the sixth, when Luna [silver]; the seventh and last, when Sol, or gold, is composed therefrom. — Those who, with our Fountain very well sealed, carry on a continual and never-ceasing cooking, see our matter first blacken, and for a long time [[ibiqs?]] it imitates, for almost [[quinqs?]] months, Saturn’s crude moisture; then, with the cooking continued, it becomes white with a certain somewhat dusky whiteness which seems to resemble the nature and condition of [[glasui?]] [glass/ice]; then it grows green and red, adorned with [[varÿsqs?]] various colors which follow the essence and qualities of Venus and Mars; at length it whitens truly and most brightly, so that it puts on the qualities and essence of Luna and of silver. (Ib. p. 190.) Moreover, our matter is changed in [[quinqs?]] five months into iron, in seven into silver, and in [[novem?]] nine into gold. (Ib. p. 192.)

The Chymists’ Fountain and the vulgar quicksilver differ greatly from each other. (1) Our Fountain produces and vivifies all things. (2) It is igneous and hot. (3) By a very light distillation it is converted into spirit and a fine body. (4) The spirit extracted from the Chymists’ Fountain is igneous and pontic [briny/sea-salt-like], penetrating, and so subtle that it dissolves metals and, once dissolved, delivers them over to death. (5) Our Fountain dissolves itself, coagulates itself, and perfects itself, nothing else at all being added. (6) In its belly and in its inmost parts it has a fixed salt, red and white; indeed it is itself wholly salt, and it gushes and leaps forth from a salt-soaked cave. (7) It has the Sun and Moon in nearest potency, and by simple cooking alone they are reduced into their ultimate act. (8) From the Chymists’ Fountain, nothing else being added to it, by simple cooking there is made the elixir and true Tincture of the Philosophers, which perfects all metals and all other natural things, etc. (Ib. p. 198.)

The author praises all the treatises included in the Musaeum Hermeticum printed at Frankfurt, [[dicilqs?]] saying that all those treatises, golden and most learned, freed him from errors and taught him the true physical matter and the [[^ & fontem [[zecretum?]]]] secret Fountain. (Ib. p. 199.)

It is necessary that the Chymists’ Fountain be extracted from two substances having the nature of salt, yet sprung from one and the same root, if the true and legitimate Fountain of the Chymists is to be had. These two materials, joined together in equal weight, reduced into [[Achool?]] [very fine powder/“alcohol” in the old sense] and most thoroughly mixed, and placed in a glass retort, with a very gentle fire increased by degrees, give an igneous spirit that is distilled.

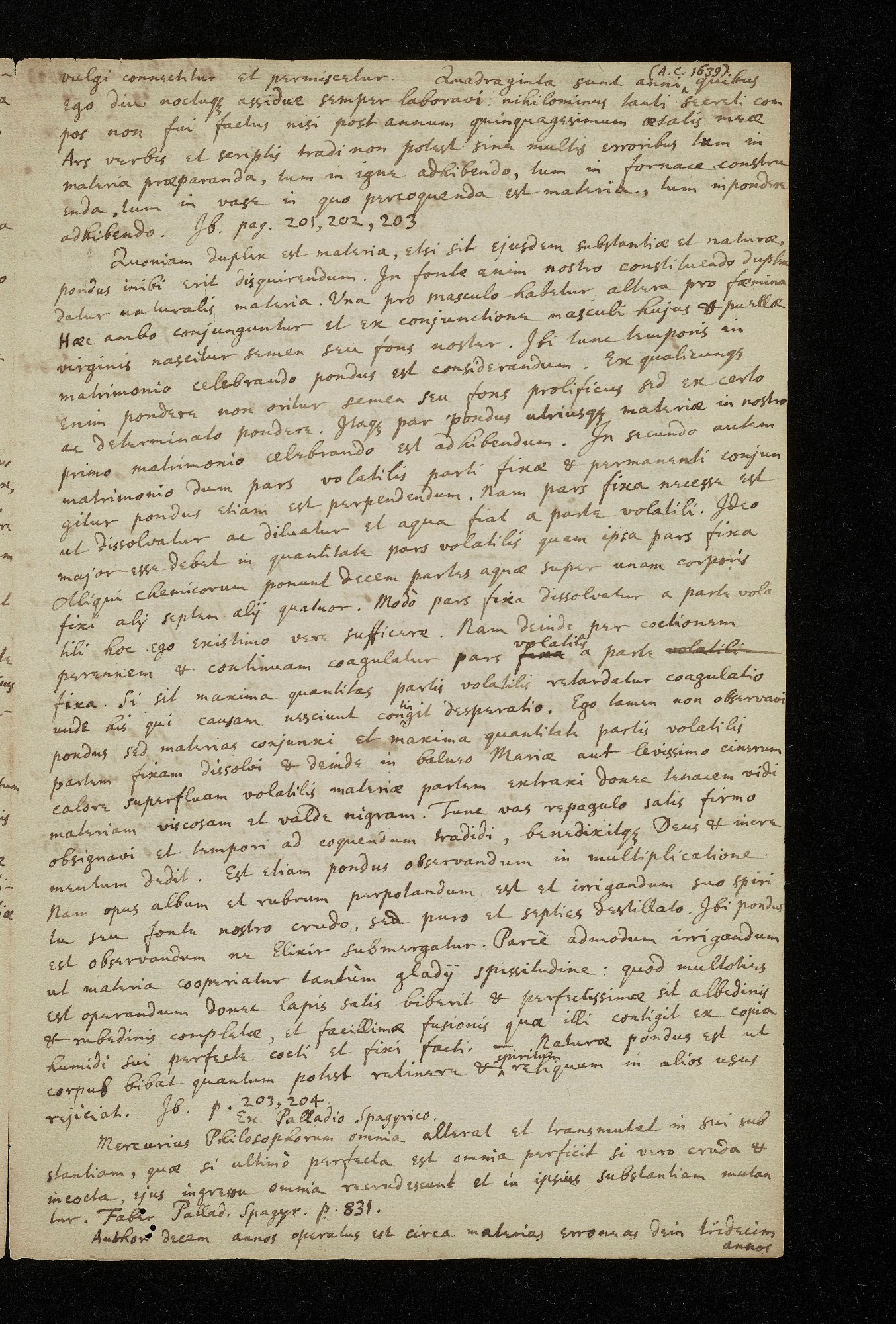

PAGE 2

It is distilled into [[perlimpidam?]] water, which is designated by various names by the Philosophers and is especially called the milk of the virgin, vinegar [[acerimum?]], water, the queen, the white woman, heaven, the tail, aqua vitae, the vulture, the sister, Mercury, the fountain, sweat, the black cloud, and by many other names; although nevertheless it is one and the same thing—namely, water, think “distilled”—from these two substances of one root, of mineral and metallic lineage. And indeed these substances, when they pour out that spirit at the bottom of the retort, remain fixed and, as it were, permanently [[velutpi?]] dead, when they have emitted their [[suum?]] spirit and life [[per?]] distillation; yet they are to be re-vivified and to rise again from the dead by pouring back their spirit upon the very materials, which, by the abundance of their spirit, are dissolved by a very gentle fire into a bloody substance and liquor which, with continued cooking and its graduated digestion, [[dirs?]] erscit & augetur—that bloody color grows—and little by little becomes from blood-red altogether black, which, with continued digestion, thickens and grows fat.

This same matter, left at the bottom before it is joined to its spirit, is likewise designated by many names. For it is called bronze, or the filing of the body with [[sulphore?]] very well calcined; the earthy and coarse part; the part to be cerated; the king; the body; ashes; the red husband; the dragon; “black, blacker than black”; the brother; coal; the sun; and by many other names. The art, however, separates the spirit from the body so that, once cleansed and made purer, they may again be joined and never thereafter be separated, but, joined together, may remain and, joined together, be perfected. For while, with continued digestion, they become thick and fat, at length they are fixed so that they may never again be separated, even if they remain molten and liquid. And this is the last sign by which our matter is denoted. The first sign is that the matter be double [[insertion]] nomine [[/insertion]]—in name—yet of the same and one genus and root. The second, that the matter be mineral and of metallic root. The third, that the matter be of very easy fusion and have volatile and fixed parts. The fourth, that the volatile and fine parts, separated and joined together, become putrid together and in putrefaction be perfected. [[Quintum?]] Fifth, that while they are cooked and putrefy, they are dyed with infinite colors—[[Timgantur?]]—and first black, then white, lastly red. Sixth, that this matter, when it is white, [[tingal]] tinges metals into silver; when red, into gold. And these are the chief signs of our matter, to which may be added that its spirit and volatile part is of a very acid taste and of a most penetrating and subtle substance, though of a pontic (briny) quality. (Ib. pp. 200–201.)

Almost all the Philosophers assert that the Chymists’ fountain, or our Mercury, cannot be perfected without gold and silver. [[Sed?]] But that gold and silver are not the vulgar kind, but are born within the very bowels of the fountain—[[Esqs?]] namely, the fixed part of the fountain, white and red, that is, the white and the red salt. Which two are one and the same thing [[quod?]], and by a different [[tespectu?]] respect are called gold and silver. For that salt, when it has the sixth degree of perfection and the highest whiteness has then been obtained, is called silver. But when that same salt has reached the seventh and last degree of perfection and has attained the final term of its cooking, then it is called gold. And without this gold and silver our fountain cannot be perfected. These metals must be joined to our fountain: with these metals it is cooked and digested and by perpetual digestion perfected—and, in the end, [it is] the same as the gold of the vulgar.

PAGE 3

…it is joined to and intermixed with that of the vulgar. Forty years [[insertion]] (A.D. 1639) [[/insertion]] have passed in which I, by day and [[noctuqs?]] night, have always labored unceasingly; nonetheless I was not made master of so great a secret until after the fiftieth year of my age. The Art cannot be handed down by words and writings without many errors, [[tum?]] in preparing the matter, in applying the fire, in constructing the furnace, in the vessel in which the matter must be digested, and in the weight to be used. (Ib. pp. 201, 202, 203.)

Since the matter is twofold, although it is of the same substance and nature, the weight therein must be investigated. In our fountain of the soul [[constilucado?]] a double natural matter is given: one is held for the male, the other for the female. These two are joined, and from the conjunction [[in?]] of this youth and the virgin girl there is born the seed, that is, our fountain. There and then, in celebrating the marriage, the weight must be considered. For from just any weights there does not arise a seed or a prolific fountain, but from a certain and determinate weight. [[Jtaqs?]] Therefore an equal weight of [[utriusqs?]] each matter is to be employed in celebrating our first marriage. But in the second marriage, when the volatile part is joined to the [[finæ & permanendi?]] fixed and abiding part, the weight must likewise be weighed. For it is necessary that the fixed part be dissolved and thinned out, and be made water, by the volatile [[parte?]] part; therefore the quantity of the volatile part ought to be greater than that of the fixed part itself. Some chemists put ten parts of water over one of the fixed body, others seven, others four. Provided only that the fixed part be dissolved by the volatile part, I judge this to be truly sufficient. For thereafter, by perpetual and continual cooking, the [[strikethrough]] fixed [[/strikethrough]] volatile part is coagulated by the [[strikethrough]] volatile [[/strikethrough]] fixed part. If the quantity of the volatile part be greatest, coagulation is delayed, whence to those who do not know the cause there [[insertion]] [[^tis?]] [[/insertion]] comes despair. I, however, did not observe the weight, but joined the materials, and with a very great quantity of the volatile part I dissolved the fixed part; and then, in a bain-marie or with the very light heat of ashes, I drew off the superfluous portion of the volatile matter until I saw a tenacious, viscous, and very black matter. [[Tune?]] Then I sealed the vessel with a sufficiently strong stopper and consigned it to time for cooking; [[benedixilqs?]] God blessed it and gave the increase. Weight, too, must be observed in the multiplication. For the white and the red work must be made to drink deeply and be irrigated with its own spirit, that is, with our crude fountain—but purified and distilled seven times. There the weight must be observed, lest the Elixir be submerged. It must be irrigated very sparingly, so that the matter is only covered to the thickness of a sword-blade; and this must be done many times, until the Stone has drunk enough and is of most perfect whiteness and of completed redness, and of most easy fusion—which befalls it from the abundance of its moisture perfectly cooked and made fixed. — The weight of Nature is that the body drink as much as it can retain and cast off the remaining [[^ spirit]] into other uses. (Ib. pp. 203–204.)

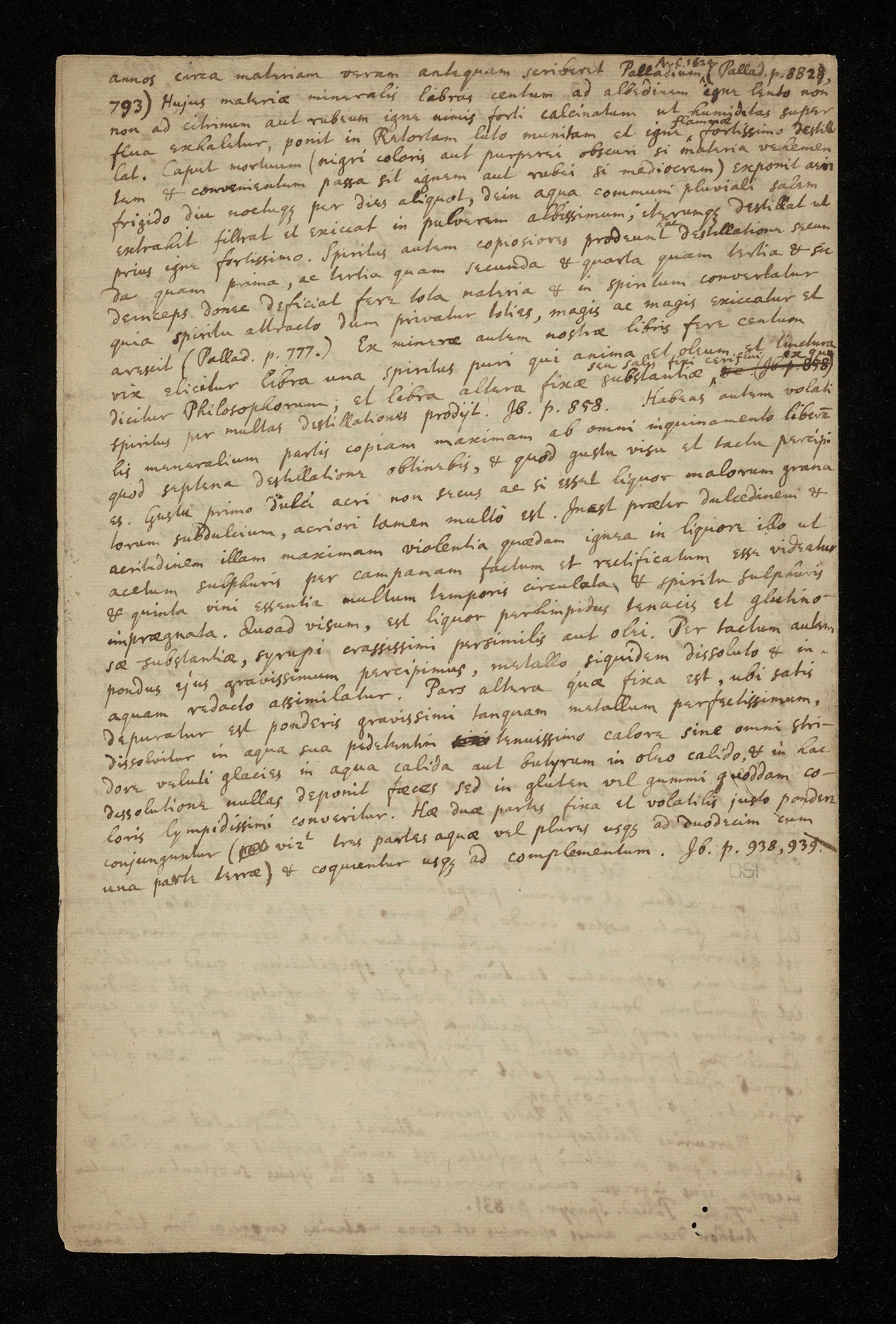

From the Palladium Spagyricum.

The Philosophers’ Mercury alters all things and transmutes them into its own substance; which, if at last it is perfected, perfects all things; but if crude and uncooked, by its ingress all things grow crude again and are changed into its own substance. (Faber, Pallad. Spagyr., p. 831.)

…years upon the [[oeram?]] matter before he wrote the Palladium [[insertion]] ^ [[A.V.S?]] 1624 [[/insertion]] (Pallad. p. 8828), 793). He takes one hundred pounds of this mineral matter, calcined to whiteness with a gentle fire—not to citrine or red with too strong a fire—so that the superfluous moisture may exhale; he puts it into a retort fortified with lute and distills with a very strong fire [[insertion]] ^ of flame [[/insertion]]. The caput mortuum (of black color, or of dark purple if the material has undergone a vehement and [[convenientum?]] suitable fire, or of red if a moderate one) he exposes to cold [[aeir?]] air for a long time, [[nochiqs?]] for several days; then with common rain-water he extracts the salt, filters it, and dries it into a most white powder; [[iterumqs?]] he distills again as before with very strong fire. And the spirits come forth more copiously in [[insertion]] [[hac?]] [[/insertion]] the second distillation than in the first, and the third than the second, and the fourth than the third, and so on, until almost all the matter fails and is converted into spirit—because, as it is so often deprived of the spirit drawn off, it is dried out and parched more and more. (Pallad. p. 777.) Moreover, from almost one hundred pounds of our ore scarcely one pound of pure spirit is elicited, which is called the soul and the oil and the tincture of the Philosophers; and another pound of fixed substance [[insertion]] ^ or of fixed waxy salt [[/insertion]] [[strikethrough]] Je. (Jb. p. 858 ex [[qua?]]) [[/strikethrough]] from which the spirit comes forth through many distillations. (Jb. p. 858.)

Now you shall have a very great supply of the volatile part of minerals, free from every contamination—which you will obtain by a sevenfold distillation—and this you will perceive by taste, sight, and touch. In taste, at first sweet-sharp, just as if it were the liquor of somewhat-sweet pomegranates, yet it is much sharper. Besides that sweetness and sharpness there is in that liquor a very great fiery violence, so that it seems to be vinegar of sulphur made under the bell and rectified, and the quintessence of wine circulated for a long time and impregnated with the spirit of sulphur. As to sight, it is a [[perhinpidus?]] very limpid liquor of a tenacious and glutinous substance, very like a very thick syrup or honey. By touch, however, we perceive its very heavy weight, for it is comparable to metal dissolved and reduced into water.

The other part, which is fixed, when it is sufficiently purified, is of very heavy weight, like the most perfect metal; it is dissolved in its own water little by little with a very gentle heat, without any hissing, like ice in warm water or butter in hot oil; and in this dissolution it lays down no dregs, but is converted into a glue or a certain gum of a most limpid color. These two parts, the fixed and the volatile, are joined in just weight ([[strikethrough]] [[pal?]] [[/strikethrough]] namely [[superscript]] [[2?]] [[/superscript]] three parts of water, or more up to twelve, with one part of earth), and are cooked [[usqs?]] to completion. (Jb. pp. 938, 939.)

LATIN VERSION TRANSCRIPTION

PAGE 1

Ex Fabri Hydrographo Spagyrico.

Fors noster Chymicus fit mineralis dum semina terræ et aquæ prævalent cæteris elementorum seminibus. Unde fors noster ponderosus valde est, pinguis et viscosus ese pinguedine aquæ & terrae quæ præeminet cæteris elementorum [[strikethrough]] [[pandeibus?]] [[/strikethrough]] pinguedinibus ex quibus solis terræ & aquæ pinguedinibus fit pondus quod in fonte nostro experimur. Hydrogr. p.187.

Gradus suat septem coctionis mercurÿ nostri seu fontis Chymici in metallis perficiendis. Primus gradus coctionis est dum argentum vivum communa & vulgare ex illa coctione emergit. Secundus gradus dum Saturnus. tertius dum glannum. quartus dum Venus seu Cuprum. Quintus dum ferrum. Sextus dum Luna. Septimus et ultimus dum solseu aurum inde componitur. - Qui fontem nostrum omptime clausum continua coctione & perenni percoquunt vident materiam nostram primè denigrasi [[ibiqs?]] per longum tempus [[quinqs?]] fere per mengus saturni crudum humorem imitari, deinde continuata coctione albescere suboscura quadam albedine quæ [[glasui?]] naturam et conditione [[on?]] vide tur imilari, deinde virescere et vubescere [[varÿsqs?]] ornari coloribus qui Veneris et Martis sequuntur essentiam & qualitates: tandem veve et candidissime albescere quad Lunæ et argenti qualitates & essentiam indua[[?]]l. Jb. p. 190. Mutatur autem materia nostra mensibus [[quinqs?]] in ferrum, septem in argentum et [[novem?]] in aurum. Jb. p. 192.

Fors chymicorum et argentum vivum vulgi multum differunt ab invicem. 1 Fors noster omnia producit et vivificat. 2 Igneus & calidus est. 3 Levissima destillatione convertitur in Spiritum et corpus finum. 4 Spiritus [[E?]] fonte Chymicorum extractus igneus est et ponticus penetrans et ita subtilis ut metalla dissolvat et dissoluta morti tradat 5 Fors noster solvit seipsum coagulat seipsum & perficil seipsum nullo alio sidi addito. 6 Habet in ventre suo et in intimis sui ipsius Sal fixum rubeum. Et album, imò totus ipse sal est & ex salsuginosa spelunca scaturit & salit. 7 Solem et Lunam habet in proxima potentia & sola simplici coctione reducuntur in actum ultimum. 8 Ex fonte Chymicorum nullo alio sibi addito simplici coctione fit elixir et vera philosophorum tinctura quæ metal la omnia perficit & reliqua cuncta naturalia. &c Jb. p. 198

Author laudat Tractatus omnes qui inseruntur Musæo Hermetico Francofurti impresso, [[dicilqs?]] quod Hi omnes Tractatus aurei et doctissi mi ipsum ab erroribus Edunerunt & veram materiam Physicam [[insertion]] ^ & fontem [[zecretum?]] [[/insertion]] Edo cuerunt. Jb. p. 199.

Fors chemicorum en duabus substantÿs salis naturam habentibus ex una tamen et eadem radice ortis eliciatur necesse, est ut verus ae legi timus Chymicorum Fors habeatur. Hæ duæ simul junctæ materiæ æquali in pondere & in [[Achool?]] reductæ & optima permintæ et in Retortam vitream posite, lavissimo igne per gradus aucto dant igneum spiritum qui stillatur

PAGE 2

stillatur in aquam [[perlimpidam?]] quæ varÿs nominibus a Philosophis insignitur & præcipue dicitur lac virginis, acetum [[acerimum?]], aqua, Regina mulier candida, cælum, cauda, aqua vitæ, vultur, soror, mercurius, fors, sudor, nebula nigra et alÿs multis nominibus; cum tamen unum quid sit, aqua puta destillata, ex his duabus substantÿs unius radicis mineralis et metallicæ prosapiæ. Quæ quidem substantiæ dum spiritum illum effundunt in fundo Retortæ, remanent fixæ & perma nentes [[velutpi?]] mortuæ cum spiritum [[suum?]] et vitam emiserint [[per?]] destillationem : at vivificandæ et a mortuis resurgendæ reaffuso earum spiritu super ipsas materias quæ copia suimet spiritus dissolvitur levissimo igne in Substantiam et liquorem sanguineum qui continuata coctione & graduata digestione ejus, in [[dirs?]] erscit & augetur color [[strikethrough]] ejus [[/strikethrough]] ille sanguineus & pedeteutim fit ex sanguimeo omnins niger, qui continuata digestione crascessit et pinguescit.

Hæc eadem materia in fundo relicta antequam conjungatur suo Spiritui multis etiam nominibus insignitur. Dicitur enim æs sive [[sulphore?]] corporis limatura optime calcinata, pars terrea et grossa, pars ceranda, Rex, corpus, cinis, Rubeus maritus, Draco, nigrum nigrius nigro, frater, carbo, sol & multis alÿs nominibus. Ars autem separabal spiritum ab Roc corpore ut iterum purgata & puriora facta iterum connectantur & nunquam in posterum separentur & simul juncta permancant & simul juncta perficiantur. Nam dum continuata digestione crassescunt & pinguescunt tandem figuatur ahibo ut nunquam amplius separentur etsi fusa & liquida permaneant. Et hoc signum ultimum est quo denotatur mate via nostra. Primum signum est ut duplex sit [[insertion]] nomine [[/insertion]] materia ej usden & unius geueris & vadicis. Secundum ut materia sit mineralis & radicis metallicæ. Tertium ut materia sit fusionis facillimæ et habeal partes volatiles et fixas. Quartum ut partes volatiles & finæ separatæ & simul junctæ putre fiant simul & in putra factione perficiantur. [[Quintum?]] ut dum coquuntur et putrescunt infinitis colonibus [[Timgantur?]] et imprimis nigro dein albo, ultimo rubro. Sextum et hœc materia ubi alba est tingal metalla in argentum, ubi rubra in aurum. Et hœc sunt signa præ cipua materiæ nostra, quibus addi potest, quod spiritus ejus & pars volatilis sit acidissimi saporis et penetrantis & subtilis admodum substantiæ etsi ponticæ qualitatis. Jb. p. 200, 201.

Omnus fere Philosophi asserunt fortem Chymicorum seu Mercurium nostrum sine auro et argento perfici non possa. [[Sed?]] aürum & argentum illud non est vulgare sed in ipsis fontis visceribus enatum, [[Esqs?]] pars fixa fontis alba et rubea, videlicet sat album et rubrum. Quæ duo unũm et idem sunt [[quod?]] [[strikethrough]] & [[/strikethrough]] diverso [[tespectu?]] dicitut[[strikethrough]] [[eo?]] [[/strikethrough]] aurum et argentum. Sal erim illud cum sextum habeal perfectionis gradum et albedinem summam est conductum tune temporis dicitur argentum. Cum verò idem ipsum sal septimum et ultimum [[strikethrough]] gradum attigerit [[/strikethrough]] habet per fectionis gradum & ultimum coctionis suæ terminum attigerit, tune dicitur aurum. Et sine auro isto et argento fors noster perfici non potest. Hœc metalla fonti nostro jungenda sunt cum his metallis coqui tur ac digeritur et perenni digestione perficitur, & ultima cum auro vulgi.

PAGE 3

vulgi connectitur et permiscetur. Quadraginta sunt anni [[insertion]] (A.C. 1639) [[/insertion]] quibus ego dice [[noctuqs?]] assidue semper laboravi nihilominus tanti secreti com pos non fui factus nisi post annum quinquagesimum æsatis meæ Ars verbis et seriptis tradi non potest sine multis erroribus [[tum?]] in materia præparanda, tum in igne adhibendo, tum in fornace constra enda, tum in vase in quo percoquenda est materia, tum in pondese adhibendo. Jb. pag. 201, 202, 203

Quoniam duplex est materia, etsi sit ejusdem substantiæ et naturæ, pondus inibi erit disquirendum. Jn fonte anim nostro [[constilucado?]] duplex datur naturalis materia. Una pro masculo habetur, altera pro fæmina Hœc ambo conjunguntur et ex conjunctione [[in?]] asculi hujus & puellæ virginis nascitur semen seu fons noster. Jbi tunetemporis in matrimonio celebrando pondus est considerandum. Ex qualicunqs enim pondera non oritur semen seu fons prolificus sed ex certo ac determinato pondere. [[Jtaqs?]] par pondus [[utriusqs?]] materiæ in nostro primo matrimonio celebrando est ad hibendum. Jn secundo auteum matrimonio dum pars volatilis parti finæ & permanendi conjun gitur pondus etiam est perpendendum. Nam pars fixa necessa est ut dissolvatur ac diheatur et aqua fiat a [[parte?]] volatili. Jdco major esse debel in quantitata pars volatilis quam ipsa pars fixa Aliqui chemicorum ponunt decem partes aquæ super unam corporis fixi alÿ septem alÿ quatuor. Modò pars fixa dissolvatur a parte vola tili hoc ego existimo vera sufficere. Nam deinde per coctionem perennem & continuam coagulatur pars [[strikethrouh]] fixa [[/strikethrough]] volatilus a parte [[strikethrough]] volatili [[/strikethrough]] fixa. Si sit maxima quantitas partis volatilis vetardatur coagulatio unde his qui causam nesciunt con[[insertion]] [[^tis?]] [[/insertion]]git desperatio. Ego tamen non observavi pondus sed materias conjunxi et maxima quantitata partis volatilis partem fixam dissolvi & deinde in balueo Mariæ aut levissimo cineorem calore superfluam volatilis materiæ partem extraxi donec tenacem vidi materiam viscosam et valde nigram. [[Tune?]] vas repagulo satis firmo obsignavi et tempori ad coquendum tradidi, [[benedixilqs?]] Deus & incre mentum dedit. Est etiam pondus observandum in multiplicatione. Nam opus album et rubrum perpotandum est et irrigandum suo spiri tu seu fonte nostro crudo. Sed puro et septies destillato. Jbi pondus est observandum ne Elixir submergatur. Parcè admodum irrigandum ut materia cooperiatur tantùm gladÿ spissitudine: quod multoties est operandum donec lapis satis biberil & perfectissimæ sit albidinis & ribedinis completæ, et facillimæ fusionis quæ illi contigit ex copia humidi sui perfecte cocti et fixi facti. - Naturæ pondus est ut corpus bibat quantum potest retinere & [[insertion]] ^ spiritum [[/insertion]] reliquum in alios usus rejiciah. Jb. p. 203, 204

Ex Palladio Spagyrico.

Mercurius Philosophorum omnia alteral et transmutat in sui sub stantiam, quæ si ultimò perfecta est omnia perficit si vero cruda & incocta, ejus ingressu omnia recrudescunt et in ipsius substantiam mutan tur. Faber Pallad. Spagyr. p. 831.

Author decem annos operatus est circa materias erroneas dein [[tórdecim?]] annos

PAGE 4

annos circa materiam [[oeram?]] antequam seriberet Palladium [[insertion]] ^ [[A.V.S?]] 1624 [[/insertion]] Pallad. p. 8828), 793) Hujus materia mineralis libras centum ad albedinem igne lento non non ad citrimem aut rubeum igne nimis forti calcinatum ut humiditas super flua exhaletur, ponit in Retortam luto munitam et igne [[insertion]] ^ flammæ [[/insertion]] fortissimo destillat. Caput mortuum (nigri coloris aut purperei obscuri si materia vehemen tem & [[convenientum?]] passa sit ignem aut rubei si mediocrem) exponit [[aeir?]] frigido diu [[nochiqs?]] per dies aliquot, dein aqua communi pluviali salem extrahit filtrat et exiccat in puloerem albissimum; [[iterumqs?]] destillat ut prius igne fortissimo. Spiritus autem copiosiores prodeunt [[insertion]] [[hac?]] [[/insertion]] destillatione [[secun?]] da quam prima, ac tertia quam secunda & quarta quam tertia & sic demceps donec deficial fere tota materia & in spiritum convertatur quia spiritu attracto dum privatur toties, magis ac magis exiccatur et arescit (Pallad. p. 777.) Ex mineræ autem nostræ libris fere centum vix elicitur libra una spiritus puri qui anima et oleum et tinctura dicitur Philosophorum; et libra altera fixæ substantiæ [[insertion]] ^ seu salis fixi ceriflui [[/insertion]] [[strikethrough]] Je. (Jb. p. 858 ex [[qua?]]) [[/insertion]] spiritus per multas destillationes prodÿt. Jb. p. 858. Habeas autem volati lis meneralium partis copiam maximam ab omni inquinamento liberā quod septena destillatione obtinebis, & quod gustu visu et tactu percipi es. Gustu primo dulci acri non secus ac si esset liquor malorum grana torum subdulcium, acriori tamen multō est. Jnest præter dulcedinem & acritudinem illam maximam violentia quædam ignea in liquore illo ut acetum sulphuris per campanam factum et rectificatum esse videatur & quinta vini essentia multum temporis circulata, & spirtu sulphuris imprægnata. Quo ad visum, est liquor [[perhinpidus?]] tenacis et glutinosæ substantiæ, syrupi crassissimi persimilis aut obei. Per tactum autem pondus ejus gravissimum percipimus, metallo siquidem dissoluto & in aquam vedacto assimilatur. Pars altera quæ fixa est, ubi satis depuratur est ponderis gravissimi tanquam metallum perfectissimum, dissolvitur in aqua sua pedetentim [[strikethrough]] [[sini?]] [[/strikethrough]] tenuissimo calore sine omni stridore veluti glacies in aqua calida aut butyrum in oleo calido, & in hac dissolutione nullas deponit fæces sed in gluten vel gummi quoddam coloris lympidissimi converitur. Hæ duæ partes fixa et volatilis justo pondere conjunguntur ( [[strikethrough]] [[pal?]] [[/strikethrough]] viz [[superscript]] [[2?]] [[/superscript]] tres partes aquæ vel plures usqs ad duodecim cum una parte terræ) & coqucentur [[usqs?]] ad complementum. Jb. p. 938, 939 [[image - short diagonal mark on page above 939]]