Mad (Raving) Wisdom, or Chemical Promises - Sapientia insaniens sive Promissa Chemica

Buy me CoffeeJacob Tollius’ Mad (Raving) Wisdom, or Chemical Promises.

Dedicated to the most illustrious and most eminent councillors (magistrates) of the renowned city of Amsterdam.

Amsterdam: printed/published by Janssonio–Waesbergius, 1689.

Basil Valentine

(From the preface to “The Hidden Generation of the Seven Planets”)

“The light of all knowledge leading to health, a long life, and riches is contained in this little book. Yet many accuse it of madness, and very many call it outright insanity. Very few there will be to whom God grants intellect, prudence, and skill to overcome all opponents by means of this work.”

Translated to English from the book:

Jacobi Tollii Sapientia insaniens sive Promissa Chemica

Jacob Tollius’ Mad (Raving) Wisdom, or Chemical Promises.

“You are mad, Paul; your great learning is driving you into madness!” so, once, with a loud voice, Festus shouted at the Apostle as he was defending himself. But he said: “I am not mad, most excellent Festus; rather, I speak words of truth and sober reason.”

“I am not mad,” he says, “most excellent Festus; but I utter words of truth and of a sound mind.”

Great learning words of truth an argument for madness! Good gods, how unfair are the judgments of the unskilled about the skilled! The blind, forsooth, will judge colors more correctly than those who see well; indeed, they will deny that colors exist in the nature of things, and will refer them among non-entities. This will be “truth”; these, “the words of a sound mind”; this, wisdom itself.

But we unhappy, senseless, delirious, foolish, mad, indeed even driven by frenzy will not merely seem so, but will be declared to be so: we who [state] things that are most true to very many, of every kind of learning (every branch of the sciences) we can prove it by arguments; we are indeed shown as demonstrators, we affirm that these things are true, and we promise that one day God willing we shall show them.

This is the reward for my good and long-continued goodwill; this is the gratitude returned for labor undertaken for the common good; this is the fruit of the deepest inquiry of my studies.

What do you think you deserve from me, you silver-lovers and chemical enemies, for whom my promises stink, and for whom my “Guidance to the Chemical Heaven” is not a philosophical storehouse of blessedness, not a treasure, not a “stone,” but an offense?

But it is not for me to look at what you deserve, but at what is worthy of me.

I promised you lately, most illustrious and most eminent men, an “Opened Chemical Heaven.” While I was unbolting its very inner chambers, such vast spaces of divine glory came before me that, astonished and scarcely myself, I stopped for some time, and I found myself uncertain and of doubtful mind whether I ought to go on, or to stop.

In that moment a dread came over me, such as often seizes those who, as they draw near to sacred shrines, are suddenly surrounded by the brightest splendor of heavenly light.

After that, a certain religious scruple followed, warning me that the revelation of the deepest secrets would be ungrateful to the Highest Deity, useless to the public, harmful to the commonwealth, and dangerous to bring out before the profane crowd.

Nevertheless, desiring to keep the faith I had pledged, and fearing to be crushed by that worn-out taunt:

“What worthy thing will this boaster give with so great a mouth?

The mountains will be in labor, and a ridiculous mouse will be born.”

I chose that way which is commonly held to be the safest, and (without betraying the innumerable mysteries which I have investigated with great care) to disclose those things which both may be a help to inquirers seeking higher matters, and may serve even for the most unfair as the surest proof that I am able to perform what I promised, if God does not hinder.

But I wished this little work, such as it is, to be inscribed with your names, most illustrious and most eminent gentlemen, so that meanwhile it may be a lasting proof and memorial of the respect and reverence which I owe you until, with God willing, I shall have set things forth more clearly.

In the preface to the Fortuitous Things I said that Basil Valentine’s Triumphal Chariot of Antimony (as far as I have learned) has been understood by no one; and I promised an explanation of it, if ever I should have more leisure. But now I dare to affirm indeed boldly to declare that no one is, or has been (except the adepts), who has understood even a single sentence of all his works, before my exposition of certain mysteries in the Fortuitous Things and in the Manuduction.

Come then: here is Rhodes, here is the leap. I shall undertake the interpretation of certain passages, but on this fairest condition: that where truth itself will reveal itself in them, and will strike the eyes of those who are half-blind with its own light, in the other things too which I pass over in silence trust shall be granted to me; and at last it shall be believed that the Philosophers’ Stone is given (exists). For it could scarcely happen that something so cautiously, and with such intricate windings, should be written about a thing that does not exist.

For no plausible reason can be devised why, with such effort and such ingenuity, so learned a writer [skilled in] the nature of things, and especially of all things in the whole, a most exact inspector of the metal-mines of all Europe, would seem to have written falsehoods he whom I myself saw with my own eyes in the secrets of very many mines in Saxony, the territory of Lüneburg, Bohemia, Hungary, Styria, and Carinthia, while he was explaining them; and I found him to be the most truthful of all writers things which until now had lain hidden from the metal-workers themselves before my testimony.

For example: from Basil I had learned that in the Rammelsberg mine of Goslar (a mine of silver, copper, lead, and vitriol) there are “vitriols” that are green like grass, transparent, and by nature hardened into crystal. When I inquired about this with the greatest care, and asked an inspector who had been employed in that mine for more than forty years, he denied that he had ever seen or even heard of such a vitriol. I asked him to investigate it more diligently. Soon afterward a boy, while turning over waste-heaps and moving the refuse, threw down something green that he had found, and I ordered him to pick it up. He brought me a most beautiful piece of green crystalline vitriol like a gem which I carried to Berlin, and there and elsewhere I distributed it among friends, who greatly admired its beauty.

I could produce many more excellent proofs of this kind in support of Basil, if it were not now foreign to our purpose. Therefore, to return to the matter in hand: from Basil I have excerpted a few passages here and there; and wherever there was even the slightest suspicion of some hidden secret, I will set down what he himself thought, even though he covered his meaning with a veil.

Therefore, in the book On Natural and Supernatural Things, chapter 11, where he treats of Mercury, page 238, German edition, last [edition], Hamburg 1677, he speaks thus:

Many worldly people do not believe this, and think it impossible (he had been speaking of philosophical Mercury joined with philosophical Venus and Mars, and fitted for transmutation and for the augmentation of the microcosm by the agency of the body or rather of the fiery, vaporous [power]) and they make nothing of it, and slander mysteries of this kind, which they do not understand in the least. But let such men be, through me, asses tasteless and foolish until illumination follows; for that does not come without the Divine will, but remains suspended until His nod.

But intelligent and experienced men, who have faithfully poured out the sweat of their brow, will willingly bear witness for me, and will affirm the truth, and will confirm it so far that they can certainly believe and admit that in these things which I write there is truth for all truth as sure as it is sure that there are heaven and hell: the one appointed and decreed as the reward of good things for the elect, the other as the recompense of evil works for the condemned.

For I do not write with my hands alone; the very inclination of my mind, will, and heart drives and urges me on, because I observe many who seem to themselves wise and very enlightened supposedly the understanding ones of the world pursuing this mystery with hatred, slandering it, defaming it out of envy, assailing it with insults, reviling it, and persecuting it even to the outermost “bark,” or even to the innermost “kernel,” which draws its beginning and origin from the center.

But I know for certain that a time will come when my very marrow will have vanished and my bones will have dried up, and then men of my kind will care for this from the deep heart with love; and, if God permits, they will gladly vindicate it from death. But that will not be allowed. Therefore I have left it in my writings, to which their faith, attention and judgment may obtain a seal of certainty and truth, so that they may bear witness about me what my final will was, and what testament I wrote for the poor and for all lovers of the mystery.

Although it by no means became me to write so much, I nevertheless could not, without a tearing of my soul, restrain myself from scattering light and brightness through the clouds by which day may be perceived, and the dark night, together with the troubled and murky rainy air, may be driven away.

So far Basil.

But who has ever been among those who have read Basil who has not simply supposed that here a monk of the Benedictine order is speaking, and that he is reproaching the enemies of chemistry for their ignorance? I confess that perhaps I have read these lines twenty or thirty times, and yet only now at last when I consider each word most attentively in the whole work, so that I may in no part fail to relate to you the Chemical Heaven have I understood.

And who has not taken the writer himself to be called Basil, and who has not believed him to have been a monk of that Benedictine order I mentioned? But if I show that this name is fictitious, and that the author borrowed it from that very Philosophers’ Mercury whom he is describing, will there be anyone who will wonder that, by no means and no labor, it has been possible to ferret out for Emperor Maximilian that monastery and the man’s station in life as is found in the commentary on the transmutation of metals by the most learned polyhistor Morhof, an intimate friend of mine?

Therefore accept the truth: our author both here and elsewhere (as I shall show) repeatedly introduces Mercury speaking under his own persona.

For to him Mercury is the Mercury of the Philosophers:

“Basil” means royal, the offspring of a king; for “basil-” is derived from the word for king. “Valentine” comes from strength or power that power which penetrates all things, generates, nourishes, increases, changes, and renews.

A “spiritual man,” because of an airy, spiritual essence, flying here and there, as I described him a little before. “Of the Benedictine order,” because to his poor “brothers” that is, to impure metals he imparts a heavenly blessing, namely his most pure, ethereal essence.

That this word has this meaning is clear from very many other passages, of which I shall bring forward one or two.

At the beginning of the Introduction to the Great Stone (p. 8), speaking allegorically, he says: “Therefore, before all other things, pray to God your Creator, that He may deem it worthy to give you His blessing in this matter.”

But he is speaking covertly about metals, under the appearance of human beings. In the last chapter of Book II, Part II, p. 226: “Pray to God with a pure and attentive heart, that you may obtain from Him mercy, wisdom, and blessing.” And soon after: “So that you may receive a greater blessing from the Lord.”

Now this “blessing” is the gift of the heavenly sulphurous spirit, from which (as I said) arise generation, life, and nourishment for things.

Likewise on p. 235: “This spirit of Mercury (namely, that which dissolves metals without corrosive action) is my primary key, the second key of which I wrote at the beginning.” And therefore I must cry out: “Come here, you blessed of the Lord; stop anointing yourselves with oil and refreshing yourselves with water; and preserve your bodies with balsam, lest they rot and stink foully.”

Here I appeal to your faith, judges of our science: for who are these “blessed of the Lord,” if not the philosophical metals, which [are produced/treated] by the Philosophers Mercury do they partake? Are they not the chemical “brothers of the Benedictine order”? I think you have now been satisfied on this point; therefore:

The name having been explained, the personification must be shown something that occurs often, but is not noticed. Do you want it to be shown at once, most clearly? Read pages 282 and 283 of this very book, where in almost the same way he excuses himself for having disclosed so many things; and then, without any distinction, he afterward introduces Jove speaking as follows: “In my dominion, among the twelve heavenly signs, Sagittarius and Pisces are assigned to me,” etc.

How, I ask, can these things be referred to our author? But they can rightly be referred to Mercury, who already passes, through Saturn, into Jove. Therefore, having now become Jupiter, he is nevertheless the same Mercury, but raised to a higher grade. This is the philosophical gradation, about which more will be said later, and something has already been said in the Manuduction.

So also at the end of page 269, that whole passage: “I am a spiritual man, subject to a spiritual state, and, by a spiritual divine right sworn by oath, devoted to the Benedictine order,” etc., almost to the end, refers to philosophical Mercury; and there too mention is made of the divine blessing which he shared with his “brothers” for their health (see also p. 345).

But in the second part of the works, chapter XIII, section 1, the personification is most open and plain Mercury brought up to the solar summit, that is, to philosophical gold so that scarcely anyone can any longer doubt this matter, especially if he considers each of the things that follow.

But very often elsewhere Basil speaks so symbolically yet in such a way that he always mixes in, as it were, certain emblems and verbal signs, by which to those who have once begun to notice these things, it is immediately clear what he means.

But let us proceed to the passage itself. “Many worldly people,” he says. In Basil, the “world” is threefold: the macrocosm, the mesocosm, and the microcosm; likewise, the world is supercelestial, celestial, and elemental.

The macrocosm, of which the discourse here is speaking, is the Earth, as is plain from page 237 (or the page immediately preceding), where he treats of Mercury joined with philosophical sulphur and philosophical salt; and from this there comes a perfect medicine of all metals (and this should be noted: for these are Basil’s “brothers”) not only to generate them at the beginning in the earth, as in the macrocosm, but also to transmute them in the microcosm by means of a vaporous body.

The microcosm is the chemical man, generated from the union of sulphur and salt.

The mesocosm is the heavenly water: philosophical Mercury, joining soul, spirit, and body that is, joining sulphur and salt.

Again, Mercury is the supercelestial world: the first moving power, the root and fountain of life, as he says on page 263.

The celestial world is spirit, that is, sulphur; the elemental world is salt.

Therefore men i.e., the inhabitants of the world are metals, but not yet purified by our Mercury.

From this follows his rebuke: “those who do not believe these things.”

Here one must know what it is to “believe” among the chemical philosophers, and what “faith” is of which mention is also made at the end of this passage. On page 231, while treating of the chemical planets and calling them the servants of the King (that is, of the Sun), he says: “Nor should one wonder that the King needs something to be changed by his servants, since their bodies are not fixed, and they admit much inconstancy, and therefore can keep faith only a little.”

Here, without controversy, faith is attributed to metals just as it is to human beings.

Let us now compare page 8 at the beginning of the Introduction: “so that,” he says, “you may obtain all the more blessing from the Lord, and may acquire ‘faith’ in heaven by the confirmation of your faith.” Here faith, the sign of steadfastness, is set against inconstancy; and the confirmation of faith is the same thing as its preservation, or else the weakness in preserving it.

Therefore, among the chemical philosophers, faith is a kind of magnetism, or an attraction of the invisible earth, that is, of the earthly spirit, by which it joins to itself the heavenly spirit of Mercury.

Hence, further on, in this same book, p. 214: “Supernatural things (that is, spiritual, invisible, incomprehensible things) must be grasped and judged by faith.” For Mercury seeks Mercury, and embraces it.

And what must also be made the chief point of my words key XI of Saturn bears as its banner Astronomy, presenting a black banner, on which faith is depicted clothed in yellow and red. For the yellow and red color of faith is perceived only in Saturn, hidden beneath blackness on which Geber speaks (Book I, chapter V).

But Saturn is the first of the metals that grasps Mercury by faith and fixes it, as we have shown in the Manuduction. This is the faith which our author here desires in imperfect metals; as also on page 117, On the Microcosm:

“If Elias were already present, made clear, if the stars could speak, and if silent nature were instructed with a tongue, I would need no testimony from this point onward against unbelievers, who do not apply their mind to understand this discourse of mine. For where a man is possessed by blindness, he can make no judgment about writing; but understanding judges by patience, and wisdom separates itself from foolishness by its own experience.”

This passage is especially relevant to the explanation we are giving of the text we are treating. For it follows: “mysteries, which they do not understand in any way” that is, they do not notice them with understanding, or (as they ought to be understood) they do not pay attention.

Then: “let it be allowed that by my judgment such men asses, lacking understanding may be, and may remain, fools.” To this corresponds the saying: “wisdom separates itself from folly.” Concerning blindness and writing, however, we shall say something a little later, when we reach that point in the context.

“Until illumination follows.” This is one of the signs by which I have explained the true sense of this passage. For “illumination” is a chemical term, and is especially familiar to our Basil in describing the Great Art.

Thus, in the beginning of the Introduction, in the place already cited (p. 8): “that your heart may be illuminated with every good.” Here “heart” is put for the center of the salty earth. For the heart of a man is the center of life. Hence, in the same author a little earlier you read about seeking the art with groanings from the whole heart, and elsewhere about praying with a pure heart, and lower down in this place about those who will take care of mine in the tomb with their whole heart where there is more on this.

“Every good” is that which comes from our heaven. Thus on p. 236: “But I judge that man to be learned who, after the Divine Word, penetrates with true understanding the earthly things which ought to be judged by skill (that is, by the spirit of sulphur), and has learned to recognize darkness from light, and to separate good from evil” that is, to separate pure sulphur from impure and combustible sulphur.

Now illumination is the spreading around of light; and our light is the light of Wisdom, which shines in darkness and yet does not burn, as he says in Key XI. For our sulphur does not burn, and yet it shines far and wide. From this it is clear that this light is heavenly sulphur, which is also mentioned in Key VII (see p. 50 and p. 263; likewise p. 21 in the Introduction), where the Chemical Old Man cries out to the people that is, to the metals: “Awake, O man, and look upon the light, lest darkness lead you astray.” These words wonderfully illuminate what has just been said.

“Which does not happen without the Divine will, but waits for His nod.” What God is to the chemists, and what His will and nod are, will be explained in the Opened Chemical Heaven, together with Chemical Theology.

“But intelligent and experienced men.” We have already spoken about understanding; likewise, who the learned man is namely, the salty spirit of the earth: that is, the one who knows and has received the light of wisdom. And the experienced men are those whom, in the Introduction (p. 20), he calls “learned men of the earth and men skilled in writing.” But we shall soon see what he means by writing.

“Who have faithfully poured out the sweat of their brow,” that is, those who have joined themselves or their salty spirit to Mercury in good faith. For sweat can be false, and it appears on the face; hence it can easily be recognized whether it is genuine or feigned.

“Faithfully,” that is, truly. Hence, at the beginning of the Introduction: “The Creator does not grant true knowledge to everyone, but only to those who hate falsehood and love it without any deceit.” It can also be explained in an “attractive” sense namely, that this sweat is joined with Mercury.

“In these things which I write,” that is, in the spirit which I communicate. For this is what writing, for us, is; and those who share in this are the men skilled in writing. Thus, in the Introduction (p. 9): “Do not forget, then, your diligent labor in the continual searching of the writing,” and on p. 11: “Writing and faith must judge this.” That is, the spirit of Mercury descending, and its …

through a most powerful attraction from the earth. Heaven and hell: more on these later in the Opened Heaven.

“For I do not write with my hands alone,” etc., “but my heart urges and drives me on.” We have already said something about the heart; but Mercury wishes, by a magnetic desire, to draw to himself that illumination of the earth. For philosophical Mercury is the magnet of the philosophers, which draws chalybs that is, the fiery, salty spirit of the earth to itself. Thus in Key V.

And just as iron has a magnet, which by an invisible and wondrous force of love draws it to itself, so too our gold (that is, the fiery, salty spirit) has its magnet, which is the first magnet of our great stone, its material. If you understand this discourse of mine, you will be rich and blessed above all the world.

And on p. 267, chapter VI, on the Sun: just as the Sun, that great lamp of heaven (that is, unfixed fiery sulphur), by a special familiarity and love strives to draw to itself the earthly fire, by a magnetic manner and nature; so also between the Sun and gold there is a peculiar friendship and a mutual attractive force, etc.

“Many imagine themselves wise, very enlightened,” etc. Here he is touching on minerals and metals especially Venus from which some think they will extract a tincture. But our author calls those minerals and metals imaginary and the men who pursue them imaginary (supposed) enlightened and wise, because their sulphur is not fixed, but inflammable and flying away in the fire.

“They persecute [it] even to the outermost bark.” Certain of those things especially minerals when added to a wise man, that is, to an illuminated chemical man, harm him; and with their corrosive sulphur they gnaw at him and attack his “bark,” indeed even to the innermost kernel, as he immediately goes on to say: they penetrate it with their poison, and infect and corrupt the fire hidden in the heart that is, in the center of the earth of which Geber speaks in many places (Part I, Book II, ch. XIV).

“Which draws its beginning and origin from the center.” Thus also on p. 233: “But matter, which draws its origin from the center, is imagined through the stars,” etc.; and on p. 132: “Having been born from the center (its heart), it spreads itself through the whole circumference of the circle and fills all things.”

“But I know for certain that a time will come when my very marrow will have vanished and my bones will have dried up.” That is, when I have been “cooked” and matured by the philosophical fire; when my moisture has been digested into dryness. And this is what, in the Introduction to the Great Stone, he says of Vulcan (p. 19): “when he kills Mercury, so that his bone is completely burned up.”

“They will care for this from the deep heart.” The word heart occurs often in our author, and signifies the center (as we have seen), or the innermost parts of the earth, or even of Mercury, if the discourse is about him. Thus in the Introduction, p. 20, he speaks of the old man, that is, Mercury: “He was speaking with a singular spirit that lay hidden in him; and his speech penetrated him with body and life, so that his soul felt it in the heart.”

“Those who will take care of mine in the tomb.” Because Mercury must be killed, so that he may be revived more gloriously.

“They will take care of mine.” Namely the Moon and Venus, of which the same p. 19 was cited.

“If God permits.” As above: because it does not happen without the Divine will.

“They will gladly vindicate it from death.” That is, they will raise it up again this is the work of Venus. Hence, on the same page 19, he prays to Vulcan on behalf of Mercury.

He says that for Mercury, his liberation from the feminine sex will be brought to completion. And he himself, a little afterward, having been revived, cries out with a loud voice:

“I was born from a woman; women have widely scattered my seed, and by it they have filled the earth; my soul is devoted to her therefore I will feed myself on her blood and will water [it].”

Against this there is the failing heart, a sign of a weak vital spirit, that is, of Mercury, and of one deprived of nourishment (on the Microcosm, p. 122). But also the powerful animal heart from the East that is, of the lion, or of salty sulphur must be devoured by the harmful bird from the South, that is, by Mercury (Introduction, p. 21).

And on p. 232, Part II, there occurs a phrase almost like this one of ours:

“Whoever therefore,” he says, “has come to know this golden seed, or its magnet, and has searched out its property, has the true root of life, and can reach that which he desires with his whole heart.”

But he will not be able to do this now; for Mercury must die so that the Sun may rise again concerning which resurrection there is more in the Opened Heaven.

Therefore I have left them these writings of mine: what writing is, we have already explained (see also pp. 406 and 412).

Their faith: see what we noted above.

Attention/notice: the love of Mercury.

“They will obtain a seal of certainty and truth”: that seal is the Hermetic seal, understood by very few up to now. Hermes Mercury is the chancellor in our art, as we shall see later.

“What my final will was”: namely, that the poor brothers that is, the imperfect metals should be helped by the resources I leave behind. They are called poor because they lack fixed sulphur. Concerning these, p. 231:

Because the Moon lacks the crown of the golden garment, along with fixity, as likewise in Saturn, Jove, and Mercury namely, in common Mercury, or living silver but not in the philosophical, fermented [Mercury], which is very different from it. Therefore he everywhere calls these metals poor and needy, as on p. 8:

“Remember, when you have been placed in a rank of honor, to bring help to the poor and needy, and to rescue them from misery.”

But most plainly in the end of Key III, p. 35:

“This is the purple cloak of the supreme Emperor in our art, with which the Queen of Health is veiled, and by which all needy metals can be warmed (revived).”

He also mentions these same things in Key VI and Key IX, where he says that as often as a new gate of entrance is opened by the fire, so often it distributes a new form and appearance of the garment as spoil, until the poor themselves have obtained riches and no longer need to be changed by another. Here the fire is now called the fire of fixed, salty sulphur, by which needy metals are warmed. And this is the garment, the golden crown; this is the purple cloak.

“Without harm to my soul.” Quite rightly because it must be joined with salty sulphur.

“I would scatter brightness through the clouds.” This light is the penetrating power of that [light], of which we spoke above. Clouds arise from excessive moisture and from the condensation of vapors rising upward. Our author, on p. 266 of On Natural and Supernatural Things, where he treats of this same light and of its sympathy with the earthly [light], says:

“Take note of this: that great heavenly light pursues the small earthly light with a singular love, because of the spiritual air by which both are driven and preserved from mortality. But when the air is corrupted by excessive moisture which it draws to itself and drinks in then it happens that by the coagulation and condensation of mists, clouds are generated; and the sun’s rays are hindered by them, so that they can be reflected less, or can send forth their penetrating power. The same principle holds for the little earthly fire: in rainy and cloudy air it never shines so brightly as in a clear sky, and so on. Therefore a cloud is an excessive Mercurial moisture.

He also speaks of these in the Macrocosm, p. 143: “Then the body will no longer be earthly (namely, after the resurrection), according to faith and scripture, as it was before; but plainly heavenly and clarified, shining like the morning star, or like the sun, when all clouds vanish.”

And in Part II, p. 215, he explains these things in detail: “But,” he says, “to John it has been revealed that the heavenly fire is the smoke of the cloud, and the vapor which, from the moisture of the earth, rises up into clouds.” Where soon after he says that the heavenly fire is to be compared to sulphur, the smoke of the cloud to salt, and the vapor to the water of the sea, that is, to Mercury in which the earth lies shut up and hidden.

“So that day may be perceived, and the dark night with the murky and cloudy, rain-laden air may be driven away.” These things have already received ample light from what has gone before.

Nevertheless I add what our Mercury cries out with a loud voice in the Introduction, p. 21: “Blessed is he whose eyes are opened, that he may see the light which was previously dark to him.”

This is a far different and much sounder exclamation than that of Festus with which we began. Therefore I will make our imaginary “blessed ones” truly blessed, and open their eyes, so that henceforth they may recognize the Chemical Light, especially the Basilian one, obscured by the darkness of many parables.

In the Repetition of the Great Stone, where concerning living lime, he treats of living lime (p. 100), praises its spirit highly, and says that it has the power to overcome and to fix other spirits.

Then, he says: “Take note: this spirit loosens the ‘eyes of Cancer,’ and also reduces crystal to a liquid. These two, joined and united by a kind of distillation, break up every stone of yours and dissolve the knots of cramp of the hands and of gout so that the gout is forced to depart.”

This most certain remedy I taught my pupil; and for the same reason the learned Chancellor of our most powerful Caesar daily gives me thanks.

I would dare to swear by Jupiter’s Stone (for our Stone is far holier) that no one who reads these things can fail to be touched by at least some suspicion of the hidden secret. Yet let the blind see what lies hidden.

Nothing is more certain, or easier to prove, than that what is described here is philosophical “living lime,” whose making, or preparation, Key IV teaches. And this living lime is the same spirit as the spirit of the dragon, which has long dwelt in stones, and slips into and out of the caves of the earth, as is in Key II.

But the whole passage must be set down, so that more light may be poured in from it. “When,” he says, “you have joined the old dragon to the eagle, and have set both upon the infernal saddle, Pluto will blow so strongly that he will drive out from the dragon a volatile fiery spirit, which by its heat will burn the eagle’s feathers; and you will prepare a Spartan bath, in which snow on the highest mountains melts and is dissolved into water.”

This eagle is philosophical Mercury, the first key; and, as he says elsewhere, the second key of this key is philosophical vinegar, or Azoth A and Z, A and Ω, N and Π. Living lime is the stone-dragon, the salt of Mars.

The fiery spirit of this dissolves crystal into liquid, and cures gouty people, as the learned Chancellor of the most powerful Caesar testifies.

But who is that faithful pupil whom he taught this medicine? Who is this Chancellor who bears witness here? Who is that Caesar? What is this crystal?

The pupil is the philosophical sulphur of Venus, as I have explained on p. 406; Basil openly indicates the rest elsewhere. Thus in Key IX, where he treats of the offices of the planets: “Mercury,” he says, “is the chancellor of all.” And hence that “seal of certainty and truth” is committed to him, as we saw above.

But in Key III: “the purple cloak of the supreme Emperor in our art”; and on p. 242: “This now is the way by which the spirit of Mercury can be compared; which way I have thus far opened, as far as it has been permitted to me by our supreme Emperor.” Here you have the most powerful Caesar.

But concerning the crystal, see p. 168, where Mercury [says]:

“The nourishing Mother has handed over to me all the colors of the world; and hence Raphael gave the angel a white jewel crystal so that I might form from it whatever work I wished. It is transparent, because it receives all colors.”

Nortonus the Englishman, in the Hermetic Museum, p. 496.

But many of the learned will wonder (as is clear) that so many various colors will appear in our stone before the perfect, clear, and unchangeable whiteness [appears], considering the small number of ingredients. To these I will answer according to their liking, and I will present the truth of that great doubt:

By the nature of magnesia these colors arise, whose nature is convertible to whatever proportion and degree just as a crystal is disposed toward its subject…

For of any thing which is in the earth, if you set crystal before it, it represents color.

Hence cease to wonder.

Basil (p. 271, ch. VII, On Natural and Supernatural Things) says that crystal is called the “common mercury.” And in the Repetition of the Stone, p. 78: “Our Mercury is made from the best metal, transparent as crystal.”

Therefore that fiery spirit of the stony dragon, or of living lime, dissolves into a liquid the crystal of Mercury that is, its water coagulated by Saturn, colder than snow, clinging to the highest mountain-peaks; and it burns the wings of Mercury himself, that is, of the eagle.

But when the crystal has been dissolved by heat like ice into water and mixed with the loosened “eyes of Cancer” (that is, with the philosophical Moon dissolved, or alkali), it loosens the stone of the philosophical bladder, and the knots of cramp of the hands and of gout concerning which remedy, God willing, [more is said] in the Commentary on the Diseases of the Chemical Man.

From this spirit of such great power I pass to another, which, being badly understood, has led even the most learned chemists into error, and has deceived the greatest princes of the world.

For what king or prince either does not have drinkable gold, or does not strive to have it? Who among chemists does not promise that, and boasts of a special method for making it?

I do not wish to deny that there is a solution of gold which can do much in medicine; but its preparation is most difficult, because the right method of preparing it lies hidden from most people.

I will say nothing here about that aurum potabile of Antonius Franciscus, Elector of Cologne, Baron of Wagnereck, or of others; but I prove only this: that no aurum potabile of that kind is philosophical.

I have said elsewhere that the philosophers’ drinkable gold is that which imperfect metals drink, so that they may attain perfect and complete health of their body; and likewise that it restores to wholeness the philosophical man or the one suffering from that disease by this [means].

It is prepared from the spirit of philosophical Mercury, from which philosophical gold is brought back into a body. Thus Basil says (p. 268):

“From this spiritual essence, and from this spiritual matter, from which gold in the beginning was formed into a body; but drinkable gold is prepared more certainly than from gold itself because first it must be made spiritual, so that from it drinkable gold can be made.”

And on p. 243:

“But this is the sum of the most secret words: without the spirit of Mercury which alone is the true key for making bodily gold drinkable the Philosophers’ Stone cannot be made.”

When bodily gold is the fixed salty sulphur, which, having been reduced into a spirit and joined with the spirit of sulphur as with its yeast, Mercury prepares the heavenly medicine.

Now then, lovers of the Divine Art, give me your most pleasing thanks, because I will so illuminate for you (also with Philalethes, chapter XIII) the exposition of one kind of bodily gold, that from this you may easily recognize in Mars the common gold that is, the sulphur of Mars, as it is in Mars, not yet drawn by the magnet.

Ignorance of this matter drove Georgius Hornius, otherwise a most learned man, into madness.

But I, a worshiper of the sparing and seldom-seen gods,

WHILE THE WISDOM THAT RAVES

“Consulted in error, now I must backtrack,

lower the sails, and retrace my course.

Do not leave me behind”

Abundantly, taking from the great conscience of a sound mind a fitting fruit for you; and I do this so much the more, because I loathe all that chatter of the rejected and the flattery of men devoted to the great ones.

For it is not enough that I should stain and defile my papers with names so contemptible; but so as to return to our author he teaches the same method of making this drinkable gold elsewhere. Thus in Part II, p. 216:

“Therefore it is fitting for prudent metallurgists to open the eyes of body and mind, so that they may understand and recognize all ores, metals, and minerals, both mined and excavated. Thus they will acquire for themselves glory and a name that will never die, with much praise: just as noble gold shines out in glory and beauty, especially when it first comes forth from its lodging; and [gold] can also be reduced into an oil, which preserves men in long-lasting health beyond every balm, and becomes a good vegetable thing to drink.”

But here it must be observed and noted that it is not so easy, for a faithful and accurate understanding of things, to translate word-for-word into Latin each point that our Basil explains with ambiguous German expressions.

For when German metallurgists are called berg-leute (“mountain-men”), that word does not so much mean laborers as men who are occupied in the mountains; and thus it more conveniently hints at the metals themselves, existing in the mountains.

Therefore the speech is directed to these, as I have shown more often above in other places.

What “prudent,” or “intelligent,” men are has already been explained. Likewise what blindness is. That “splendor of glory” is that illumination spoken of above.

The lodging is Mercury, or the radical moisture, in which philosophical gold is shut up [gold] which can easily be reduced into oil…

This “good vegetable [thing]” is this same gold dissolved into a spirit that is, philosophical Mercury by which the metals “drink.”

For (as I shall explain more fully elsewhere) those three kingdoms Vegetable, Animal, Mineral for true chemists are Mercury, Sulphur, and Salt. Hence in our author’s Introduction, p. 9: “Some call our stone a vegetable work; which indeed it is not; yet because it grows and increases, they therefore call it vegetable.” But it grows through the changes of the planets up to the highest perfection.

Further, from this drinkable gold appears Basil teaches on p. 80 where he says: “If fixed sulphur is fed with unfixed sulphur, the spirit of wine is drawn through the alembic into a vessel, red like blood; and it is called drinkable gold, able by no art to be reduced into any body.”

Yet nowhere more clearly than in the second part of the work, Book V, p. 343, does he explain what true drinkable gold is where he proposes three kinds of it, of which one is the true and principal drinkable gold, the second is nearest to it, and the third he calls, as it were, a kind of intermediate drinkable gold because of its outstanding powers.

“The highest,” he says, “and the chief drinkable gold, which the Lord God alone by nature has infused, is cooked and purified, and fixed by the substance of the stone itself, to which it first comes as a ferment. It is far more excellent and more effective than the most precious drinkable gold that can be found anywhere in the whole world; for it is a heavenly balsam, and derives its origin from Heaven, and has received its body from the earth; afterward, when it has been brought, after its highest purity, to supreme perfection, it is a universal medicine of men, and also of metals; but of these, where it after fermentation it has been reduced into a tincture. But the metals, by the work and benefit of this, are converted and changed into the highest amendment and health that is, into the purest gold.

Here “men” are to be understood philosophically just as also philosophical metals, or the seven Basilian planets, of which more below.

The second kind, nearest to this, is that which is prepared from fixed red sulphur (that is, the most purified bodily soul of gold), by the addition and conjunction of the universal spirit of Mercury.

The third is a certain particular medicine, which because of its remarkable virtues ought to be called something like a halfway drinkable gold.

Here it must be noted what is meant by “particular” among the chemists: not what the pseudo-chemists sell from cinnabar, or from mountain red sulphur, or from lapis lazuli, or from mercury, and the like (for from such things no true “particular” is given; since from a trunk, as Sendivogius says, branches are sought in vain); but rather when Mercury is changed into Saturn, Saturn into Jupiter, Jupiter into Mars, Mars into Luna, Luna into Venus, and Venus into Sol (which metamorphoses are taught by the six earlier keys of Basil) then truly this work is a particular.

For when the philosophical Sun has been fermented and brought on to augmentation and multiplication, it is called universal which a little before was set forth under the name universal medicine.

That this is so may be proved from p. 241 of this second part, where, speaking of the philosophical Moon, he says:

“The humidity of the Moon has not yet been entirely taken away, although it has reached the degree of fixed sulphur; but by this quality it is held even in a low degree…

Nor does our King warm his cold body with his own fervent seed an operation that then belongs at once to the particular works. Likewise, in Part I, p. 231: “But when our King has received tribute from his servants, he endures and overcomes cold and fire more easily than leprous metals; and thereafter, increased by this growth, he becomes the ruler and victor, in a particular way, over all the rest.” More proofs could be brought forward, were it not better to avoid tedium.

But since the whole plan of this work is exceedingly intricate, I will, with a mind inclined to the common advantage, set down this: that what in the Manuduction I almost only touched on as by the way, I will now explain more fully and more exactly adding certain points less obvious, yet neither unpleasant to know nor useless.

On the difficulty, thus Norton:

Now after this you must know all things:

The seven circulations of each element,

Which agree with the number of the seven planets;

Which no one knows, unless by heavenly grace.

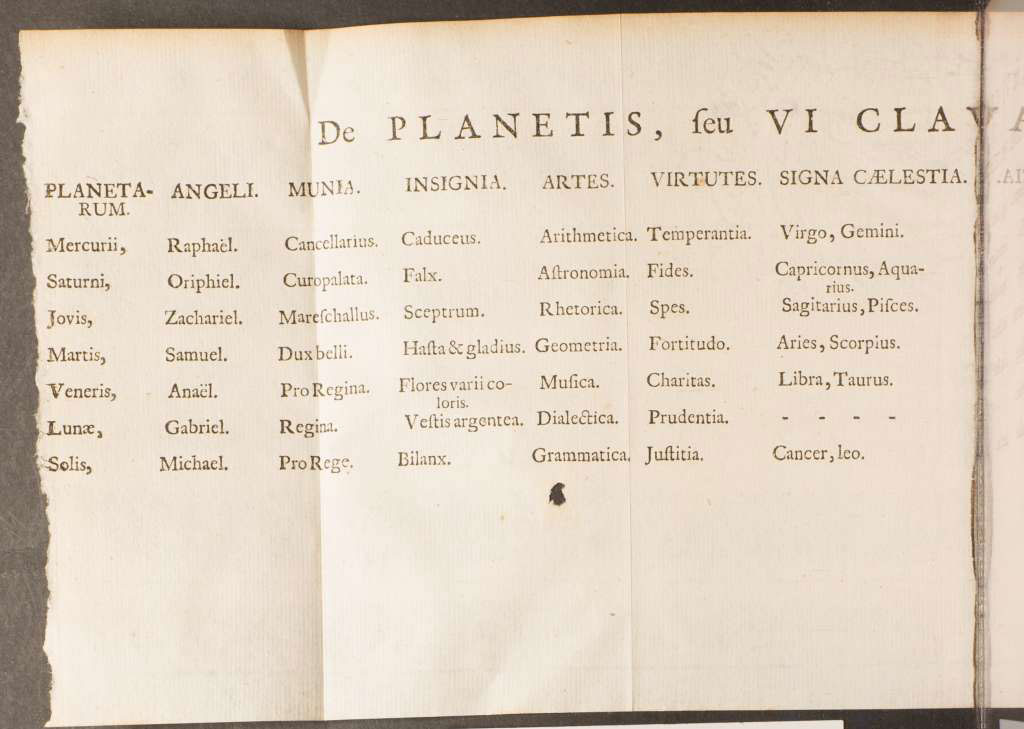

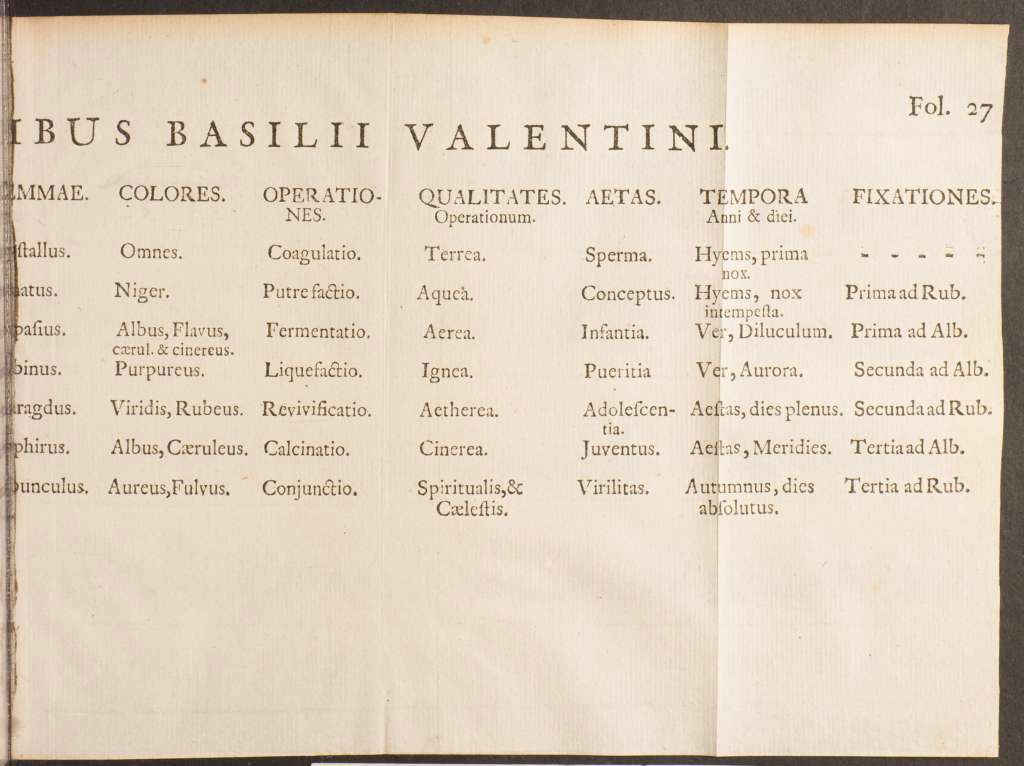

But so that I may do this as plainly as possible, and so that the reader’s attention be not drawn aside by the variety of things attributed to many planets, I will place all the Planets together with most of what belongs to them under one view, and set before your eyes a compact survey in a table (for there is not leisure now to recount and illustrate everything; and part of it you may seek from my Fortuitous Pieces, concerning Trees, Flowers, Animals, rites, etc.), and I will explain it as the matter requires.

Table of the Planets.

On Mercury

Our author did not set Mercury among the planets as the topic of the six preceding “keys”; rather, because Mercury is common to all, and truly (as the Greeks say) Hermes is knowledge, he dedicated his Introduction to Mercury: for from Mercury the beginning of the Philosophers’ Stone arises, and thus Mercury becomes the guide of the journey to everlasting happiness the beginning of the chemical work, whose end is the Sun.

Therefore (I think) the angel Raphael is assigned to Mercury he who was also the guide and companion of the younger Tobias on his journey; and the divine physician who freed Tobias’s wife from evil spirits (she having been bereft of her former husbands), and restored the use of his father’s eyes. For among the Hebrews Raphael is “the Physician of God.” We have explained elsewhere that Mercury is the messenger of the gods, and the guardian deity of roads and travelers.

Here, then, we shall have Mercury as the universal parent of medicine, and the minister of Potable Gold as Janus, the opener and the closer of every blessedness and health.

The office of Chancellor is given to him (as above), and there we also showed that the Hermetic Seal is entrusted to him not the common one, but ours, as the philosophers say. Concerning this, Philalethes in the Manuduction (p. 785) says:

“This is the heat of the lamp, which, if it is moderate, makes the matter circulate daily, until, the moisture having been dried out by calcination, the second fire produces ashes in which the vessel, or the water, is hermetically closed and sealed, according to the saying of the philosophers: ‘Take the vessel, strike it with the sword, take its soul; this is the closing.’”

The emblem of Mercury is the caduceus, that is, the twofold rod surrounded and entwined by a double serpent, by which it restrains what is light and fickle; it pleases the golden throng of the gods above and below.

The two serpents represent two spirits: the fixed and the volatile. Of these, Philaletha likewise says (p. 788):

“Sulphur and living mercury of which the first is fixed, the second volatile are compared to two serpents, or dragons: of which the winged one signifies the volatile nature of the one, while the one without wings denotes fixity.”

Among the arts assigned to Mercury is Arithmetic, because all things consist in number, weight, and measure. Thus Nortonus:

“For God made all things, and surely ordered them

in numbers, weights, and measures.”

The same author shortly afterward, when he treats of the conjunction of the four Elements which will follow in our Saturn (that is, Key I) adds:

“Join them together also arithmetically,

by subtle proportional numbers,

a matter of which little has yet been known,

since Boethius wrote: ‘You bind the elements by numbers.’”

Basilius, in On the Macrocosm (p. 144):

“Between the heavenly and the earthly there is a great difference, as regards faith and intelligible substance; nor is the difference less between the sidereal and the earthly: since the sidereal is observed and penetrated by imagination alone, with the aid of arithmetic; but the earthly by contemplation and separation. Imagination belongs to Mercury, as contemplation belongs to Saturn.”

Moreover, just as Mercury is the beginning of the Work, so from that same arithmetic (that is, numerical) beginning the ordering of the planets begins.

There is also present in it the virtue Temperance; since, before the conjunction of the elements, their mixture/temperament ought to be exact, and care must be taken that nothing outweigh or excel. Hence come the precepts so frequent among ourselves and others about observing weight, or the degrees and regimen of the fire.

To the Virgin Mercury the Virgin also is faithfully joined, together with the Twins (Gemini). Nothing is more common in our Art than virginal milk, nothing than an immaculate and uncorrupted Virgin. Concerning this, Philalethes (ch. X) says: “This sulphureous fire of Mars is the spiritual seed, which our Virgin (remaining nonetheless undefiled) conceives; because an uncorrupted virginity is able to admit a spiritual love according to the Author of the Hermetic Secret, and according to experience itself.”

Hence the error of those men is exceedingly ridiculous who seek “Virgin Mercury” in Idria, on the borders of Carinthia and Friuli; as that was shown to me there, which in that famous mine is expressed from the ore without fire and which is sometimes also, though very rarely, found (as is commonly observed) slippery, and flowing like water. Nor is the astonishment of those difficult to understand who dig up “virgin earth” from beneath lakes.

To such men I shall point out in Basilius the virginal milk, for restoring the strength of a spirit grown languid he calls that (p. 279) an animal sulphur. For the milk of the Virgin is a sulphureous spirit, by which the Philosophical Mercury, coagulated in the womb of the virgin earth through Saturn, is nourished and grows into a man. Our author On the Microcosm (p. 118) says: “But this vital spirit, or Mercury, is fed and sustained by the fatness of human sulphur, in fatness (pinguedine), which rules in human blood.”

Basilius likewise, Key V, says: The Spirit of Life is the life and soul of the earth, which dwells within it, and from heaven and the stars works into what is earthly. For all herbs, trees, and roots, and likewise all metals and minerals, receive their powers, their increase, and their nourishment from the spirit of the earth: because spirit is life, which is nourished by the stars, and thereafter supplies food to all vegetative things (i.e. to Mercury), and like a mother bears the fetus in the womb and nourishes it. Or, as Cicero says (De Natura Deorum, book II, ch. 32): “The earth, pregnant with seeds, brings forth all things and pours them out from itself; embracing them with shoots, it nourishes them; and it itself grows, and is in turn nourished by the higher and outward natures; and by its exhalations the air is fed, and the aether, and all things above.”

Concerning this, I have written at length certain things in the Fortuitous (Fortuitis), from Sendivogius and others, which may be consulted.

Gemini indicates the hermaphroditic nature of Mercury, concerning which (also) in the Fortuitous. And then (there is) both spirits, the Mercurial and the sulphureous, volatile who, when joined with the spirit of the Virgin-earth, are hardened into a Mercurial crystal. For thus he himself says of himself in Basil(ius), in verse:

“Gemini and Virgo bestowed the hardness of the Crystal.”

Therefore the Crystal is also assigned to him as a gemstone (as has already been indicated); and from the chemical operations (comes) passive coagulation. For if an infant is to be conceived, it is necessary that there first be a coagulum of seed or sperm. Yet coagulation is not a substantial form, as Norton rightly observed, but at least a passion/affection of a material thing. Mercury, moreover, is the first matter of the Stone, and the seed of metals. But the coagulation of Mercury as it is (set forth) with our author on p. 88 is found in Saturn; which on p. 17 (is called) “imprisonment” he calls it ‘incarceration.’

To coagulation he assigned Earth as the fixed origin, if Basil is to be believed; but according to others, the internal heat of the earth.

Hence Sendivogius, Tract. V:

“All water is congealed by heat, if it is without spirit;

it is congealed by cold, if it has spirit.”

But whoever knows how to congeal water by heat and to join spirit with it, will certainly discover a thing a thousand times more precious than gold; that is (to give light here by other things also), whoever is able to congeal the Mercury of Antimony into regulus, by the most hot sulphureous spirit of Mars, in fusion with salt, niter, and tartar, will indeed have procured for himself something of the greatest value.

Whoever is unwilling to believe me here, let him consult Philaletha; and so he will begin to see the truth.

Moreover Earth is assigned to Saturn, of which presently.

The beginning of the year’s season is winter; of the day, the first is night. Age is not observed in the seed, but in a man already born; nor does fixation have place in it, since it is still soft and slippery quicksilver.

On Saturn

The first key sets Saturn before us; that is, Mercury already coagulated and bound by Saturn the first metal, and the beginning of our stone (p. 243, Part II).

The angel added to it by Basil is Oriphel a word which can be explained in different ways. For if the first letter has been corrupted from o into u, so that it becomes Uriphel, it will mean “the fire of the divine mouth,” like Uriel; and our author elsewhere mentions this angel, together with several other angels of the planets: it is the light, or fire, of God.

But if it is read Horiphel, it is “a cave, or” either a hiding-place, or even the excrement of the mouth of God, can be explained. And indeed, in that Saturnine putrefaction, and in the separation of excrements, the last etymon of that angel can scarcely be seen, αωθσ-. But since we do not know the Hebrew tongue, we leave that to others to be examined more exactly.

Saturn, moreover, performs for our Venus the office of a Curopalates. Now it is known that the Curopalates’ “introduction” belongs to the receiving of foreigners who arrive at the Prince’s palace, and that he admits them from there to the Prince; indeed, that the whole care of the palace also lies upon them. Therefore by Saturn that is, by putrefaction the palace of Mercury is “opened,” and the spirit of Mars is admitted to Mercury.

But to restrain the palace household, a sickle was granted to him, by which he cuts down and reaps every impurity of combustible metallic sulphur. Hence, in a poem in Basilius, he speaks of himself thus:

I stand as a fatal abyss for impure metals;

The harshness of my sickle cuts down what is anxious, and struck by sure peril of life,

and drives it on to Orcus.

Furthermore, just as Saturn is the highest of the planets in the heaven, so also among the liberal arts the supreme one is consecrated to him: Astronomy. For in the highest region of the sky the stars rule, and the constellations complete their course, says our author (p. 179). And just as he himself is the beginning of the philosophical work, so also the stars, spiritually and incomprehensibly, generate the minerals (p. 216). We read in Zoroaster the principles of the world and the risings of the stars most diligently, to have beheld without”:

Here, by Apuleius and others, he is counted among those whom natural magic has claimed for itself, and has enrolled among the practitioners of our art.

This beholding of the stars and of heavenly things our author calls speculation that is, a grasping of supernatural matters by the power of the mind, insofar as it is permitted to rise to so lofty a summit.

Therefore, in the last introduction (which we said was given to Mercury), when it was now necessary to proceed to Saturn when Mercury’s discourse (that is, the old Philosopher’s) had ended each of the planets, or metals, withdrew again to its own place, and gave itself over to deep contemplation, by day and by night.

But in the clearest words (p. 216) he joins speculation to Astronomy, where he says that the nature of the visible “supernatural” things namely heaven, the planets, and the stars is to be observed by a “speculation of computation,” which belongs to astronomy.

And by this indication many passages that are obscure (and ἀνὴρ μωτιδη) and difficult to understand become so clear and plain that they lie open to anyone as at p. 262 and 305 of Part I, and p. 233, 242, etc. of Part II which I will not set down here.

Yet one thing (p. 144 of Part I, in the Microcosm) seems worth adding: there he teaches that, with regard to the penetration of the earthly body that is, of Saturn one must look to speculation, and to separation.

“Speculation,” he says, “is made by purpose, and separation by doctrine. The former is spiritual: because the spirit of man does not rest, but desires to investigate and penetrate the many properties of all things. For each spirit, as though by mutual love, draws to itself one like itself.

The separation of the earth is this: whereby he separates an earthly body from its spirit by the Chymical Art, so that the one may be distinguished from the other. Therefore speculation is the magnetism of the spirit of the earthly salt, of the heavenly (principle) drawing sulphur unto itself.

To Astronomy is joined Faith, because heavenly and supernatural things, and thus things incomprehensible, are grasped by faith. Concerning this matter enough has been brought forward above.

The celestial signs assigned to Saturn are Capricorn and Aquarius, “the well of Winter,” frosty with moisture.

He adorns him with the gem Garnet, a symbol of blackness through putrefaction. For that gem by its own nature bears a black colour hidden secretly within itself, as is with our author in the Triumphal Chariot, p. 362. And this gem was to me Ariadne’s thread, which out of the vast errors of this study like out of a most intricate labyrinth unravelled me and led me forth. Wherefore the mention of all this is always most pleasing to me.

Black colour is a sign of putrefaction, or of solution. Hence “to dart with black colour,” meaning “to dissolve,” is a Chymical manner of speech with our writer, p. 314. “Many,” saith he, “torment Antimony in strange ways and excarnify it.” (Mark these words, you who write commentaries upon the Triumphal Chariot, or who prepare medicines from it according to the letter:) “but without fruit, and with labour and cost; because they wander from the right mark: for the reason of ‘darting with black colour’ escaped the eyes of their mind; so that they could neither observe it rightly, nor give heed to the soul.” Moreover, out of every thing that hath moisture mixed with it, blackness may be drawn forth by the help of fire, saith Flamellus.

And the reason it is ready at hand. For if heat acts upon a moist and thick matter such as Saturn is then a black color is produced from it. For thickness makes darkness and a privation of light. But if, on the other hand, the color which comes from light is removed, blackness will appear, as it does in Norton in the Ordinal.

As to putrefaction, which is assigned to Saturn, it must be known (says Sendivogius, tractate VI) that winter is the cause of putrefaction, since it freezes the vital spirits in trees. When these are dissolved by the sun’s heat in which there is a magnetic power attracting all moisture then the heat of nature, stirred by motion, drives to the circumference a subtle vapor of water, which opens the pores of the tree and makes drops to trickle down, always separating the pure from the impure, etc.

But our author indicates it somewhat more plainly in Key VIII: “Whatever is to be born through putrefaction must necessarily be done in this way. The earth, hidden and shut up with moisture, is brought to corruption and destruction: this is the beginning of putrefaction. Yet by this warm property it must needs kindle itself and expand; without which no birth can be brought forth. Therefore, that it may obtain the vital spirit here, air is required, and its assistance.”

Putrefaction, then, is of water, and for that reason it requires the winter season of the year, because winter is moist and soaked with waters. Thus Alze’s book in the Museo Hermetico, p. 334, rightly says: “This work must be begun in winter, which is moist.” Then indeed let us draw off the moisture up to spring, which grows green, so that then, under labor in a gentle fire, colors may also appear to us. Then we proceed to summer: and then the work must be made into powder with a strong fire. Lastly we come to autumn: and then, as the fruits ripen, we arrive at the noble redness of the work. Nor are the motions of the stars and planets to be attended to, as is read in certain books.

For our truth it is a certain temporal thing, in which the spirit we seek lies hidden by which we tinge (things), and make glass so that it can endure the hammer; and (it is) about changing crystals into carbuncles (gem-stones).

These last two points about malleable glass, and about turning crystals into carbuncles are chiefly to be noted first. To make carbuncles out of crystals is to change Mercury, through the order of the planets, into the Sun, or rather to bring it to perfection. For just as we showed above that crystal is assigned to Mercury, so too Basilius in his poem assigns the carbuncle to the Sun, saying of the Sun: “A shining carbuncle-gem adorns the child’s head.” Concerning malleable glass I could speak at length, if circumstances allowed; for now I will state it briefly, and in only three words (as they say): all those are mistaken who count that Petronian tale mere chemical sport of wit among true things. For in the nature of things, or by any art whatever, you will find no other malleable glass than that which Philosophic Mercury produces when it has been cooked out and matured to the highest fixity this is, when from crystal it becomes no longer a carbuncle, but true, pure gold.

For this warning, I say, that learned Frenchman who provided a most learned commentary on an Italian poem by a certain chemist who took for himself the name “Brother Marco Antonio Crassellami,” and who entitled both little works in French Light Rising from Darkness (“The light coming forth from the darkness”) will thank me, whenever this small commentary comes into his hands and before his eyes. And I approve his conjecture of taking “glass” for the true meaning in that poem for this reason: that our vessel must be sealed with the Hermetic seal not in winter, but in spring, as (I have) brought forward above.

“This is clear from Philalethes’ words. But it has seemed neither foolish nor useless to copy here these few Italian verses:”

Although I know well that, unless

the oval vessel is sealed in winter,

no noble vapor ever stays within it;

and that, if prompt assistance

(with lynx-eyed sight and a skillful hand) is not at hand,

the white infant dies at its very birth;

and that, later, he no longer takes as food

his first humors

like the man who in the womb is nourished

on impure blood, and afterward on milk in swaddling-clothes.

“Therefore one must read in the second verse, ‘to seal the oval vessel of glass.’ For the vessel of Mercury is glass indeed even crystalline which must be sealed in the ash-fire. It is called ‘oval’ because it is compared to an egg, as we indicated in the Manuduction.”

“But to return to the Philosophical Winter: Basilius speaks thus in Key VII: ‘In winter the common crowd of men reckons all things dead, because the cold has bound up the earth so that nothing can grow or be born from it. But as soon as spring appears, when the force of the cold has been broken by the rising of the sun, all things are called back to life: trees and grass show themselves to live; and creeping things, which to avoid the harshness of winter had hidden themselves in caves within the earth, creep out again from these into the open air; etc.’ where the creeping things represent Mercury to us.”

“It is still midnight: when the conceived infant is warmed in the womb, and nourished, and, as it were, fixed. For this is its first fixation, which leads to solar redness. Hence some men, as our author notes elsewhere, have called ‘lead (as) gold,’ and ‘gold (as) lead.’

On JOVE (Jupiter)

Zachariah has given Jove the name “Jovis παρίδεως” (as it is written here), the most fitting of all. For it is the whiteness, or brightness, and the splendour of God a colour which a little later will be claimed for Jove.

He seems to call the same thing by another name, or to substitute another for it, in our author’s book On Natural and Supernatural Things, in the chapter on Jove; where he names Zedechiel, whether this one or that one that is, the justice of God, which suits Jove equally well.

For the office assigned to Jove is that of the Marshal of the Palace, whose task is jurisdiction and command in the service of the court. “Jupiter,” says our author, “is good and kindly; not too hot, nor too cold, of a moderate temperament between the moist and the dry.” Hence he also holds the middle place among the metals.

For this reason the ancients consecrated the navel to him, as is found in Callimachus, in the hymn to Jove; and he himself was once worshipped among the Africans under the surname of Hammon, in the form of a navel-shaped image, as Quintus Curtius testifies in his history of the unconquered Alexander the Great. Among the Greeks too he is for the same reason called ἐμφάλιος (emphalios, “of the navel”).

Now the navel is the middle part of the body, as I have shown from Vitruvius in the Fortuitous Things. He also procures (as our author further relates) that under his rule strict discipline is observed, and that to each person his own right is allotted.

The badge of this power is the sceptre, or the marshal’s staff, by which he commands peace that is, quiet to all; and therefore he is called by our author (p. 278) the God of Peace. And this sceptre is made of olive-wood, which is sacred to Jove; about which I have written somewhat more in the Fortuitous Things. The reason is the sweetness of its oil, sweeter than all sweetness.

But otherwise he says, by the spirit of his mouth, which is hot, and dries up and consumes the moisture of Saturn. Hence he bears before him the banner of Rhetoric. For thus he himself says in a poem:

I render what is owed to the rich, and punish the wrongs of the needy,

when my tribunal has been approached.

Therefore my right hand, with royal sceptre, must be feared;

and Rhetoric calmly holds the measured rule of the tongue.

So good a Prince what else does he do except make good hope? And to him the white colour is fitting; whence white lilies were to the ancients the symbol of hope. That Virgilian line is well known: “Give lilies with full hands.” And even on those ancient coins Hope (Spes) held a lily-flower in her hand.

But someone will say: “Yet the banner of Jove, in Basil (Book) XI, is of an ash-grey colour.” I admit it; but he himself explains it in a poem, and says that an ash-grey colour also sometimes belongs to him, but in winter: that is, when the whole moisture of Saturn has not yet been cooked out by the fire of Jove. For heat works out from black an ashen-grey, then soon white, then yellow, and finally it produces a red colour.

Therefore to him also, and to Saturn (in respect of a greater fire being applied), all these colours are assigned. The reason, moreover, is plain. For the more earth a body has, the more opaque it is. Hence Saturn is at first black. Water mixed with earth makes an ash-grey colour. The more water there is, the more the body becomes diaphanous (transparent). But clear matter, such as water, is the matter of whiteness. Yet it cannot be clear except through air, whose property is to give light to dark things.

But if to this matter there should be added its form namely dryness, with all moisture consumed by heat then whiteness is perfected.

And hence Jupiter King of the White Crown is what Basil, Part II, p. 276, calls him. Then, as heat grows more intense, the yellow colour (as I said) is produced; and at last, with the fire increased, the red is born such as appears in Saturn and Jove as minium (vermilion). But to return to Jovial Hope, that gentle goddess is now already fixed in evident whiteness. For one cannot pass from black to red, unless whiteness has intervened.

Jupiter has under him the heavenly signs Sagittarius and Pisces; concerning which our author, on p. 283, gives this reason: “From a fish,” says he, “I, Jupiter, was born, because before the entrance into life I was in watery moisture; but Sagittarius directed his arrow into my heart, so that I might lose my moisture, and through heat might come forth worthy of the dry earth.” What the arrow means for you, I explained in the Fortuitous Things; and what the heart means, in the preceding pages. Hence there is an unspeakable harmony of all these things, and from that inexplicable harmony the truth of our art is made manifest.

The topaz stone, which from white turns yellow, is, because of the colours already explained, among the ornaments of Jove.

Among the chemical operations, Fermentation is assigned to Jove, for it belongs to the air. Becher, in his Subterranean Physics, describes for us a threefold fermentation: of which the first kind is swelling, or warming; the second is fermentation properly so called; the third is acidness.

Here one must speak chemically, not in Latin, as often elsewhere; nor is there leisure to dwell with Jove over trifles such is the “splendour” of his style, which was once attempted by us with care, and perhaps not unhappily. For in our Jove, Rhetoric is furnished and adorned with the splendour of things, not with the magnificence of words.

Swelling, therefore, to return to it, comes about when heat, whether innate or infused whether in something dry, or in something fat and viscous acts upon the moisture mixed in: hence arises rarefaction. Such as is seen in a seed, when it begins to sprout.

Fermentation takes place in temperate air of which sort is that attributed to Jove; because, just as cold, which is in Saturn, condenses, so excessive heat thins out (rarefies).

Souring (acescentia) occurs through rarefaction, or the raising up (exaltation) of the saline parts. For that is sharp/pungent (acre) which is extremely rarefied. And from this the method of preparing Philosophical Vinegar can be learned.

Among true and worthy chemists there is much talk of a threefold ferment; but it is so little understood, that I cannot sufficiently wonder at this very fact. I will teach this also, as the rest provided only that no one wishes to be taught by reason of pride or contempt of me.

There are three ferments in our Basil: the first is when Mercury is animated by its sulphur; the second, when Mercury, now already animated, is fed with its salt that is, when the Red Lion and the Green Lion are joined. And these two are the Philosophical ferments, concerning which our author speaks most plainly in Part II, p. 275.

The third is when the Philosophical man is restored/refreshed, or the Philosophers’ Stone is increased, and is fermented with common gold or silver.

I will add also an explanation of another little chemical term, and I will show what the soap of the Philosophers is. “Fermentation,” says the same Becher, “consists of saline and sulphurous particles namely unctuous and viscous ones, that is, earthy and watery which, when temperately mixed, are so disposed that the saline particles are easily raised up, thinned, and made sour, and, like soap, mix themselves with water and with any liquid whatsoever.”

Compare these things with what went before, and you will understand what chemical soap is.

The most delightful season of the year, when (it is) opened/unlocked.

When, with the sun’s temperate heat, all things on earth sprout, and burst forth into leaves and flowers, and gladden mortals with cheerful hope, Spring is rightly consecrated to Jove. Hence the divine Poet:

In spring the earth swells, and calls for the generative seeds.

Then the almighty Father, the Heaven (Aether), with fruitful rains,

descends into the bosom of his joyful spouse,

and, great himself, mingled with her great body, nourishes all the offspring.

The kindly field gives birth, and the Zephyrs, with their warming breezes,

loosen the bosom of the plains; a tender moisture abounds in all things;

and the grasses dare, in safety, to commit themselves to the new suns;

nor does the young vine-leaf fear the rising south winds,

nor the rain driven through the sky by mighty north winds;

but it thrusts out its buds, and unfolds all its leaves.

Nor could tender things endure this labour,

if so great a calm did not pass between cold and heat,

and the indulgence of heaven did not receive the lands.

Now Spring is the year already begun as it were the dawn of the day, and like the infancy of a man, who has just come forth from the mother’s womb into the shores of daylight.

To these things corresponds the fixation of Jove, which is the first step toward whiteness concerning which colour the foregoing pages may be consulted.

On MARS

Wonderful, as I said, is the chemical harmony not only of things, but also of names that agree with the things. So here, when our Basil adds Samuel as the angel of fiery MARS, who stirs him up to enter bravely into battle with the impure Philistines.

We have already, from the inmost heart, offered prayers and groanings to God; and we have shown that the Heart is the centre of Mars, that is, of the salt of the earth, to be of the earth, expecting help and the coming of the heavenly spirit. And behold, I shall have heard Samuel as the leader of prayers. For God heard the voice of her who called upon him with her whole heart, with groanings Hannah, poor and afflicted.

In this expedition Mars is the leader of war, armed with a spear and a sword. And indeed he is of a marvellous colour, and, like a fiery mirror, shining with a ruby brightness. Each weapon is a symbol of the spirit that is igneous, flying, and penetrating; and in the Fortuitous Things one may find it, where I have spoken of the spear of Cadmus and of Achilles, and of the sword of Vulcan, of Mercury, and of the Sun, and of other weapons of that kind, drawn from the history of fables.

Nor is it without purpose that our author compares the sword of Mars to a fiery mirror. For you will find no word of this sort in all Basil that is written without some hidden mystery beneath it. Wherefore he rightly warns in various places as on p. 94, 324 of Part I, and Part II, p. 301, etc. that these things must be most diligently observed.

I will add an example, which at the same time explains the preceding passage about the head of Jove. In the poem mentioned, Jupiter thus speaks of himself:

To whom, far and wide, the roaming seeds of the earth are known,

the eager one calls me from the blue Englishmen;

whither for me the way is first through the salt waves of the sea.

These things, taken simply, are seen to have been said, as in the English proverb, which is held to be excellent: that the sea must be crossed by one who is going to that island. But whoever observes more carefully will perceive that Jupiter says that the sea must be crossed, not for that man who seeks Jupiter’s riches, but for Jupiter himself which to one who does not understand could at once seem ridiculous and absurd; but to one who understands, not so.

Anglia, to the Germans and Belgians, is Engelland, that is, as much Angel, and thus it signifies the region of the Angles. In this ambiguity the author plays, and he hints at a region of spirits, that is, the air which is the middle region of the heaven and that it is the airy homeland of Jove.

But our Jupiter must pass over the Philosophers’ sea, which is salt. Basil makes mention of this on p. 21, where he says that, with the Lion rising and the Bird at midday, the great salt sea must be entered. Likewise in Key III, p. 34, where he warns that the wise sulphur must be sought in a like sulphur, yet it cannot be found unless the body has first passed through the salt sea. And in Part II, p. 237, where he teaches that the sun, that is, the heavenly sulphur, must be killed by the salt water of the salt of the stone and of sal ammoniac (that is, of the stone of the eagle and of the stone of the dragon, which together constitute the second key).

Now the Eagle, most pleasing to the divine king, is sal ammoniac, and (as I have already explained) it is the principal spirit of Mercury in Basil; and it is shown to be the key of this second key.

But the stone Dragon is the saline spirit of fire, the salt of the stone, or the nitre of the Philosophers; which, like calcined tartar, by its causticity attracts to itself the air, or the sulphur of the sun, because the air in it is resolved into water. This is that which Jupiter, as we have just had, must enter as the salt sea.