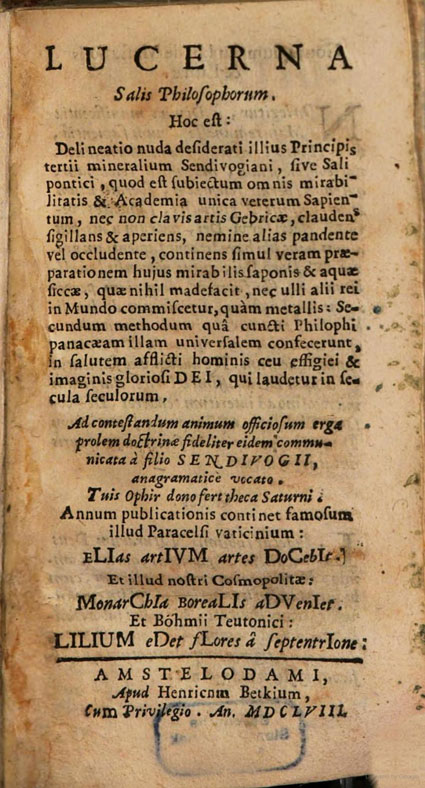

Lucerna Salis Philosophorum - The Lamp of the Salt of the Philosophers (The Lamp of the Philosophers Salt).

That is:

A bare delineation of that much-desired third principle of minerals of Sendivogius, namely the Pontic Salt, which is the subject of all marvels and the sole academy of the ancient Wise, and likewise the key of the Gebric art—locking, sealing, and opening, no one else either revealing or shutting. It containeth also the true preparation of that wondrous soap and of the dry water, which moisteneth nothing, nor admitteth mixture with any other thing in the world, save with metals only: according to the method whereby all the Philosophers attained that universal panacea for the health of afflicted man, as the image and likeness of the glorious God, Who be praised unto the ages of ages.

To attest a dutiful mind toward the offspring of doctrine, faithfully communicated to the same by the son of Sendivogius, anagrammatically named.

“Tuis Ophir dono fert theca Saturni.”

The year of publication containeth that famous prophecy of Paracelsus:

“ELIas artIVM artes DoCebIt.”

(Elias of the Arts shall teach the Arts.)

And that of our Cosmopolite:

“MonarChIa boreaLIs aDVenIet.”

(The Northern Monarchy shall come.)

And of the Teutonic Böhme:

“LILIUM eDet fLores à Septentrione.”

(The Lily shall put forth flowers from the North.)

Amsterdam,

At Henricus Betkius,

With Privilege. Year 1658.

Contents of the book:

1. DEDICATION

2. Preface

3. On the Third Principle of Mineral Things

4. Chapter 1 - The condition and quality of the Salt of Nature.

5. Chapter 2 - Where is our Salt to be sought?

6. Chapter 3 - On Solution

7. Chapter 4 - How our Salt is divided into the Four Elements, according to the Philosophical Understanding

8. Chapter 5 - The Preparation of Diana, white with snowy brightness

9. Chapter 6 - On the Marriage of the Ruddy Servant with the White Woman

10. Chapter 7 - On the Degrees of Fire

11. Chapter 8 - On the Miraculous Efficacy of our Saline-Aquarian Stone

12. Recapitulation

13. Catalogue of Authors - The more illustrious, and therefore the most profitable to be read

14. The Authorities of the Philosophers in Harmony

15. Chapter 1. On the Antiquity, Supreme Excellence, and Certainty of the Chymical Art

16. Chapter 2. Concerning the Requisites of the Seekers of the Art

17. Chapter 3. The Matter of the Stone must be Metallic

18. Chapter 4. On the Origin and Generation of Metals; and that All Proceed from One Root

19. Chapter 5. On the Genuine Subject of All the Philosophers, and that the Whole Art is from One Thing

20. Chapter 6. On the Reasons for Making the Preparation

21. Chapter 7. On Sublimation and the Salt of the Wise

22. Chapter 8. On Water, or Mercury

23. Chapter 9. On Solution

24. Chapter 10. On Body, Soul, and Spirit, and the Rectification of the Species

25. Chapter 11. On Conjunction

26. Chapter 12. Of the Effects of the Panacea, or the Philosophers’ Elixir

27. Chapter 13. On certain expedients and abbreviations in the Chemical Art

28. Epilogue

29. DIALOGUE - Further uncovering the Preparation of the Philosophers’ Stone

30. TO THE READER

31. ADMONITION - Of the Publisher of this Treatise.

32. APPENDIX - Of a certain Dialogue, once held betwixt the Spirit of Mercury and a certain Monastical Philosopher.

33. The Dialogue of the Spirit of Mercury.

34. LATIN VERSION

It is not read that from the Divine bounty a greater gift of wisdom ever flowed forth, whence Hummel: “commend to memory, adorn the conscience, magnify science; for he that despiseth science despiseth that God most high and glorious.” But the wise and elect servants of God, each after another, by grace and gift of God (blessed be His name), inherited this wisdom, and to make for themselves an eternal remembrance among posterity, wrote concerning this their books in typical and tropic expressions. For books are vessels of memory and perpetual fame of the wise. And lest this wisdom and gift of the most high God, so joyfully bestowed upon the microcosm, should tend to destruction, at the call of God the Philosophers and Prophets of the Lord of sciences placed the course of this wisdom revealed in writings.

“Praised be the sublime God of Natures, blessed and glorious, Who revealed unto us the whole order of Medicines, both by the experience of this Magistery which, by the goodness of its investigation and by the constancy of our labour, we sought out, beheld with our eyes, and touched with our hands the completion thereof, searched out by our mastership.”

DEDICATION.

Glory be to God on high: peace on earth: good will toward men: and upon all that sincerely fear God, the eternal blessing of the most holy Trinity.

Although, O venerable cultivators of the Hermetic Muses, nothing (as the distinguished anonymous counsellor of the Conjugation of the Sun and Moon saith, in the third part concerning the Mass of the Sun) can be newly invented in the Philosophical art beyond the sayings of the ancient Philosophers—since at least the matter is one, and its way unique—yet the very delight of this secret, falling together into the mind of the understanding one, doth often pleasantly stir him, that with a small literal unfolding he should before the venerable society of this magistery congratulate himself (hinting with Geber) upon having understood the most hidden knowledge of the Philosophers, and should also, so far as lawful, point out the way unto the same for other still unskilled searchers.

This according to the exhortation of the Ancient Arab, who in his book of Chemistry thus speaketh:

If I be of great reason in the science, and the tropes of the hidden Philosophers be opened to me, and that be manifest to me which they concealed, and I apprehend this by science, then ought I rightly to bring this near to the understanding of my successors, with words open yet veiled, signifying an hidden and covered sense, so that it be both open and concealed. Open to the studious, wise, intelligent, and inquirers; concealed to the less intelligent. If I do not so, I shall not manifest my diligence to those before me. And God shall be witness for me against you, that ye forbid not those who are worthy of our brethren, nor reveal these things unto the unworthy; otherwise ye act unworthily, against conscience, and shall merit punishment from God, Whose name be glorified. For this science hath been committed to you, that it may succour our poor brethren. And God shall recompense.

This therefore was the general intention of the ancients, which to me also, their most humble disciple, was as a lanthorn, that I might not deem it superfluous to publish, not long ago in the German tongue, the delineation of Sendivogius’ third Principle, or the Philosophical Salt (since not a few had hitherto desired it), for those to whom it might be welcome, briefly also indicating what then moved me thereto. But afterwards, when I came into familiar acquaintance with certain other learned lovers who were not Germans, I myself rendered the said delineation into Latin, and enlarged it with the golden sentences of the ancient sages (who shall ever remain our teachers so long as this World endureth), containing the chief doctrines of this Art, and again destined it for the light of the press, doubting not that such a little treatise, of what sort soever it be, shall be acceptable to some. For if it happeneth to come into the hand of the illuminated Philosophers, let such be in friendly wise admonished by me, far more vile than they, and I do earnestly beseech every one of them by God, Who suffereth His Sun to shine alike upon the good and the evil, that they withdraw not the gifts granted them wholly from their neighbour, nor suffer their mind to be possessed by doggish envy; considering how great a sin envy is, inasmuch as that catalogue of the wicked, who shall not inhabit the future new Jerusalem, putteth dogs, that is to say the envious, in the first place (Apocalypse 22:15).

But if there be any whose capacity hath not yet apprehended the secret of the ancients, and who desire to apprehend it, surely they shall here find faithful instruction of this mystery, even as I once received it from the living mouth of a true Philosopher: in which matter I do heartily beseech God to grant unto many both understanding and blessing. I hope also that in very truth the time shall at length arrive, when mankind shall cease from this deadly vanity, whereby now the whole World destroyeth itself, and with clearer eyes shall better acknowledge the spiritual Worker of all wonders, the almighty Creator, without Whose omnipotent providence no human body, from a little seminal water, could ever have been coagulated into such hard bones, flesh, veins, red blood, and the like; and much less could man, after his birth, have found all things necessary already prepared for him, without the daily creation of God, namely fruits and animals for food, wood and stones for habitation, and diverse metals for instruments, all which things by the divine working power are alike hardened out of a thin seminal liquor, and daily brought forth. For it is indeed most marvellous, that an aqueous liquor should be able to harden into such compact bodies of metal, sounding when struck, and extensible under the hammer—bodies which are needful to all men in this whole World, both rich and poor, especially iron, without which no tree could be felled, no house built, no field ploughed, no lock fastened with a key, no ship constructed for navigation, nor any island ever inhabited. Whence also the art of working metals was long since in use, even before the Flood, as we read in Genesis 4, that Lamech, the son of Methushael, Cain’s great-grandson, begat, of his wife Zillah, Tubalcain, who was the instructor of every artificer in brass and iron.

Since therefore, as hath been said, metals are such wondrous bodies, consisting of dry and yet flowing water, without whose help scarce any man could sustain his life—for every one necessarily needeth some habitation prepared with the aid of metals, against rain, snow, and cold, seeing that without houses and garments men cannot live, although examples there be of some men that have lived many years without meat or drink—hence the ancients with greatest admiration clearly beheld in such things the most exact providence of the Creator over every mortal, and therefore earnestly exhorted their fellows unto acknowledgment and gratitude toward God the Creator of all those benefits. They also went before them with virtues and good examples, and day and night with many labours speculated and laboured in divers ways, how they might by ocular demonstration show forth the wonders of the Almighty Creator unto the ignorant, and stir them up to follow; which their good intention so pleased the All-knowing Creator, that He inspired into them the knowledge and operation of many things, and chiefly of the aforesaid dry water. Their mind perceived that all metals had grown out of it, and that somewhat far more perfect might be made therefrom, if first all heterogeneity, which was superfluous in the generation of metals, were separated, and thereafter that pure Ens, even as the bosom of Nature cherisheth the before-named bodies, were cooked. This thing, by divine inspiration, they undertook and accomplished, and attained unto such perfection, that they could not otherwise name the same thing than the Blessed Divine Stone, as being given of God; and because with it they afterwards wrought unheard-of and supernatural things, which no other natural wit could perform or emulate, therefore they were called by men wise Masters and Magi, until that Pythagoras came, who would in no wise be called wise, but only a Philosopher, that is a lover of Wisdom, because none but God alone is truly wise. Which title of Philosopher was afterwards in general ascribed unto the learned, even unto this day, although the greater part have not understood that mastership of Philosophy, yea some have altogether disbelieved it.

But those ancient Philosophers, who by Vulcan and the Chymical art brought the same into use and for the benefit of posterity, consigned it to letters, though enigmatical, parabolical, and figurative, in such wise that it should neither become wholly vulgar, nor yet lie utterly hidden. Moreover, not a few grave men believe and admire even to this day, that the Spirit of God did sometimes marvellously play in that their mystical style, for certain of their sayings have proved as it were prophetical, though they had not the word of God in Scripture. Thus that great Greek Philosopher Plato, in his Alchymical writings, in marvellous wise (as blessed Augustine noteth in the Sum of his Confessions) wrote the beginning of the Gospel of John: “In the beginning was that Word, and that Word was with God, and that Word was God. The same was in the beginning with God. All things were made by it, and without it was made nothing that was made. In it was life, and the life was the light of men: and the light shineth in darkness, and the darkness comprehended it not.” Which very words Saint John the Evangelist, born long after him, wrote likewise.

There are also found in the book Turba Philosophorum, which Pythagoras gathered, certain notable sayings that most aptly agree with some articles of our Christian faith. For instance, when those ancients name their Stone “the Son of a Virgin,” declaring that His mother was a virgin and His father had not known her carnally. Likewise: that the Stone dieth of itself and of itself riseth again.

Also Milvescindus saith there:

“The Creator of souls, when He slayeth these creatures, after He separateth the souls from the bodies, will restore unto them their souls, that He may judge and reward them.”

And Bonellus there likewise:

“All things live and die at the nod of God. And there is a nature which, when moisture or burning befalleth it, and it is left by night, then it appeareth like unto a dead thing. Then doth it need fire, until the spirit of that body be drawn out and it be left by nights, as a man in his tomb, and be made dust. These being lost, God will restore unto it its soul and spirit; and infirmity being removed, that thing is strengthened, and after a shining it is renewed, even as man after the resurrection is stronger and younger than he was in this world,” &c.

And Hermes, in the first of the seven treatises:

“Unless I feared the Day of Judgment, I would reveal nothing of this science, nor would I prophesy unto any,” &c.

And many suchlike things, so that not without cause Rhases in a certain epistle hath written, that the Philosophers magnified themselves above all others with this, and foretold things to come.

On the other hand, the Divine Prophets in their prophecies sometimes employ similitudes conformable to the terms of the Chymical work, as the excellent natural philosopher Petrus Bonus of Ferrara witnesseth in his Margarita pretiosa novella, chapter 9, saying:

“That if I should not offend our Christian faith nor transgress the Law, I would dare affirm that certain of the ancient Prophets had (if it be lawful so to speak) the art, as Moses, David, Solomon, and some others, and likewise John the Evangelist; and they mingled it with the sayings of the Lord, and hid it therein.”

Whence Rhases, in the Lumen Luminum:

“By serious administration I judged it worthy, that it should be reduced to its own nature. Wherefore the sense of this discourse I placed in the Law of Moses,” &c.

And Rosinus:

“God rightly bestowed it upon Moses,” &c.

And Alphidius in the book of the Prophet Malachi:

“Concerning this matter of purification, we read that it was well foretold by the Prophet: ‘He shall sit as a refiner all the day, and shall purify the silver, and shall purge the sons of Levi.’ By which purgation there shall be made a new heaven and a new earth; and all flesh shall behold its salvation, when it shall know itself to be cleansed from all corruption, and to return unto the pristine health wherein it was created,” &c.

By these sayings, the holy Word of God is not profaned, but rather our Christian faith is made the more certain, when we perceive that the mystery of our blessedness and of our union with our Lord Jesus Christ is not only confirmed by God in His Word, but also hath in Nature so precious and manifest a testimony, that it was even made conspicuous to certain heathens (by the inspiration of God, as they themselves confess), as is everywhere set forth in the doctrine of the ancient Philosophers. Let any man gainsay it that will; yet I am altogether astonished, and exceedingly marvel at that great concord and likeness between this most famous secret and the salvation of man. For even as our Saviour, in His manifestation in the flesh, appeared most vile and contemptible among men, Who yet was the supreme and almighty Son of God, and nevertheless put on all our carnal qualities (sin excepted), and assumed the whole misery of man, and suffered a violent death, and rose again—for otherwise by that most holy Corner-Stone (as the Scripture calleth Him) men could not have been tinged unto eternal life—so it standeth altogether with the metals to be tinged. For the highest in heaven is the lowest in earth, and the same thing that tingeth all is wholly alike to them, yet far more abject, and it dieth for them, and it riseth again, and by its tincture infinitely tingeth them unto perpetual perfection. Therefore it is a fair and holy mystery, of which Morienus and other enlightened ones have exclaimed: This magistery is nought else but the secret of secrets of the most high and great God; for He Himself hath commended it to His Prophets and Philosophers, whose souls He hath placed in His paradise.

And as the fulness of the most holy Trinity dwelleth bodily in our Lord Jesus Christ, and all things were created by Him; so also, according to the testimony of all the Philosophers, the three principles of all things are found in perfect conjunction, corporally, in this Stone, and no creature can live without it. And even as the greater part of the world erreth in the knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ, and a vast number of those who ought to teach Christ in humility do, by their pride, fall into Antichrist and seduce both themselves and others, because they abide not in the most humble Christ: so likewise the proud professors of the liberal arts, who should teach this simple art to others, themselves know it not, because they abide not in the lowly simplicity of Nature.

Moreover, herein is our great calamity, that we ever despise the better and choose the worse, deceived by appearances; even as the Jews would fain have received John the Baptist for the Messiah, rejecting Jesus, Who wrought far greater wonders. So likewise here it happeneth, that men ever run after more specious subjects, namely gold and common Mercury, and pass by our universal solvent, which to outward sight is not so fair; whereas hitherto all have found that the vulgar Mercury hath not in itself its proper agent whereby it might perfect itself, even as those eggs which come without the cock cannot bring forth chicks. In contrast hereunto the Philosophers have named this Stone Living Silver (Argentum vivum animatum), describing its principles obscurely, so that few, by reason of the obscurity and the infinite names of this one Egg that containeth all things in itself, have been able to attain the true knowledge of it. To meet this evil, in the new Chymical Light of Sendivogius, it hath been supplied, and the most manifest series of the three Philosophical principles therein disclosed.

But when he perceived that the third, concerning Salt, had hindrances in its communication, I was willing and bound, in honour of this gracious father, to issue such a declaration, dedicated and dutifully offered to those to whom it shall be pleasing. For those to whom these my slender services shall not be agreeable, but despicable, may leave them unseen and feed their eyes elsewhere, since neither hurt nor profit shall thereby accrue to me, and I have long known that no man can so comport himself as to please every one. Moreover, though not every one may here find the whole order of the Art prescribed (for to none is it lawful so to write), yet book doth explain book, and this little book will freely afford enough of usefulness, and point out the residue to be found, so long as diligent reading of good Authors be continued, until the whole situation of Arabia Felix, or the great kingdom of Geber, be most exactly known. For then there will not be so great cause of fear, lest the fleet of the artificer perish and be broken in the ocean of labour, as it befell King Jehoshaphat, of whom it is read in 1 Kings 22:48, that he had ten ships of the sea, which should have gone to Ophir for gold, but they went not, because the fleet was broken at Ezion-Geber. But he who likewise shall go thither only for the sake of gold, and not solely to acknowledge the wonders of the Creator, shall surely experience a calamitous shipwreck both of body and soul.

Let every disciple of the Art therefore attend unto the best counsels of our forefathers (some of which I formerly consigned rhythmically after each chapter in the German, and here have likewise rendered them in Latin). For never hath it repented any man to have obeyed the wise; and from them also have I this faithful counsel, that I advise the benevolent Reader in such wise, and set forth those things which I know shall be profitable to him, as followeth:

These things, with the following, I have written in the land of John Dee, toward the close of the year of Christ’s nativity.

O ye prudent men, where do ye live? I earnestly entreat that we converse together.

Preface

To the rightly-minded Reader

That God, Who in six days created this World, after the course and term of those six great and universal days shall have been finished, will most inwardly renew it, and establish it into an everlasting, crystalline, living, unfading, and perpetual eternity—an unpassing celestial essentiality existing in the most lucid and inexpressibly shining brightness of the infinite and all-present glory of the Lamb of God and the Orient from on high—not only hath His own most true mouth and that of His servants affirmed in the Holy Scripture, but the same also may be seen, as in a mirror, in the book of temporary Nature, in the work of regeneration of the Philosophers, by means of the Philosophical Key which alone openeth and shutteth, in all time to whom Divine Wisdom granteth such a gift. In this mirror the living image of the beginning of creation, of man’s fall and the curse of the world, of the work also of redemption, and of the future most blessed restoration of all things, is visibly beheld by the worthy artificer. Concerning these matters, from Hermes Trismegistus even unto our own times, not a few Philosophers have written much and borne true testimony, as their indubitable attestations sufficiently appear in that notable book Turba Philosophorum and in other writings of the wise, so that it is altogether superfluous to cite them here.

Nevertheless, that hidden mirror of Nature (styled by them the Secret of the Philosophers) from its first discovery, because of the unworthiness and abuse of men, was most carefully concealed and hidden, so that always out of many thousands scarcely one could attain unto it, until at length, in these last times, when the clock of the World is running down to its final close, the long-obscured light of Nature, by the will of the Most High, hath made itself visible in many, who, with minds illuminated concerning the said miracles of God, have written both theologically and philosophically. Among these also was our father, now resting in God, dearly beloved, Sendivogius, whose published New Light of Chemistry is known and precious to the wise in almost all Europe. They grieve not a little that so excellent a companion of theirs, so stout a champion of Philosophical truth, and stronger than all contrary traditions, should have been hindered by idle, tasteless, and venomous slanderers, so that he might not lawfully bring forth the remainder of that incomparable talent entrusted to him, which, beyond his earlier most celebrated works already made public, he had promised.

But since the free mercy of God hath likewise granted unto us knowledge through this great Magistery, it is our purpose to follow the footsteps of our father, and to declare also to the sons of truth the third principle of minerals—most greatly desired hitherto—namely the Salt of the Philosophers (for of Mercury and Sulphur the aforesaid Lumen already containeth an excellent description), and to communicate it faithfully. Wherein we doubt not that we shall thereby obtain some grace with those who are well-disposed, but incur reproach and slander from the adversary and mocking party. Yet (God be witness) we seek herein nothing else than to serve our neighbour fraternally, and not, like the unfaithful and slothful servant, to hide in the earth the pound of gifts granted us by the Father of lights, but to exercise it with gain and increase in honour of the Most High. Therefore we care nothing for any man’s sinister judgment against us, nor throughout all this life shall we seek any vain glory or earthly felicity—though indeed the obtaining of such things seemeth nearer unto us than unto others, to whom the treasure of Nature is unknown, and since we possess that all the precious things of the world are to be found in some vile dung, if only a mad desire of such things (which God forbid) had filled us. But verily we willingly leave such coveting to those who permit their mind to be carried away by avarice (the root of all evils), or to be puffed up with pride, or inclined by worldly pleasure. Our whole joy rather, and desire, and vow, and all our confidence is in God our Creator, Who revealeth His mysteries to them that fear Him, and Who hath also opened to us this secret Mirror of Nature (which never at any time shall be seen by any unregenerate person), concerning which we shall here, as far as is meet, give some indication—together with this dutiful promise: that so far as this third principle shall be found pleasing and acceptable to the sons of the mysteries, perchance they also may, through us, become partakers of the Harmony of Sendivogius.

We would also admonish them to aim at the most inward sense of this little treatise, for all true good of things is inward, and not outward, and is for the most part to be found in such a subject as outwardly seemeth contemptible.

Yet this we have not written for those who already understand such things (of whom, however, the number is exceedingly small, beyond what any man would readily believe), but only for the grace and profit of those who, by Divine invocation, give themselves to the knowledge of such matters. And let each of them take this counsel from us: that he desist not, nor ever omit daily to prostrate himself before the throne of Divine grace, and by fervent prayers weary the heavenly Father to obtain the Holy Spirit, sighing from his whole heart in this wise:

“I beseech Thee, O Lord, most mighty God, most high and most greatly to be revered, who keepest covenant and mercy with them that fear Thee and keep Thy commandments: I, miserable worm, bow myself before the footstool of Thy gracious throne, and with my stammering tongue offer unto Thee most humble thanks from the inmost centre of my heart, for all Thy kindness, grace, and mercy, wherewith Thou hast dealt with me from my mother’s womb. Above all, that of Thy gracious clemency Thou hast made known unto me, that I can in no wise please Thee, unless Thou Thyself give it me, and lead me by the Spirit of Wisdom in Thy ways. Therefore I groan unto Thee, by the bitterness of the death of Jesus Christ, that Thou wouldst vouchsafe to bestow upon me wisdom and understanding, that I may know what pleaseth Thee, and may ever be found Thy faithful servant. O Jehovah, I am Thy servant, the son of Thine handmaid: suffer me to find grace and mercy before Thine eyes, and cast me not away from Thy children. Give me Wisdom, which for ever encircleth Thy throne; send her forth from Thy holy heavens, and from the throne of Thy glory, that she may grant herself unto me, and labour with me; for without wisdom proceeding from Thee I am nothing, nor can in any wise discern Thy holy will and good pleasure. Impart unto me the spirit, the mind, the virtue, the grace, and the charity of Jesus Christ, that thereby I may be utterly reborn, and delivered from the sins which cleave unto me without ceasing. And use me in this world unto the service of Thy children, to the glory of Thy Name. Make me a vessel of Thy mercy, and draw me into the purity and brightness of Thy most perfect Divine charity, that therein I may be wholly immersed, and that in me may die whatsoever Thou Thyself art not. Lead me by Thy Spirit in Thy ways, and grant me to remain faithful unto Thee, even unto the end of my life. Vouchsafe unto me, O Almighty, most beloved Lord, by Thy infinite omnipotence, that I may never decline from Thee, but by unconquered faith and divine strength may inseparably remain affixed and united unto Thee. Make to shine forth from me ever the noble and precious life of Christ, and to bear real fruits. Grant me also means and opportunity that I may be of use in this world to my brethren and sisters, and gladly serve them with all those things which Thou hast granted unto me.

O Jehovah! Jehovah! Jehovah! Who hast created me, and by Thine own heart redeemed me from eternal death—may I, I beseech Thee, be wholly commended unto Thee. To Thee be praise, honour, virtue, power, and glory from every creature, for ever and ever. Amen!

By such or similar sighs of a humbled and contrite heart daily poured forth unto the Almighty, most glorious Father and our Redeemer, so far is it, my brotherly Reader, that any good (that is not to the hurt of the soul) should be denied us, that rather we attain unto the very Divinity itself, and become utterly divine, higher than all angels; for all things are ours, and we are Christ’s, and Christ is God’s. O man, O man, never forget this, and faithfully commend and devote thyself unto the most holy wounds of Christ.

I. F. H. S., Son of Sendivogius.

Whose name is given by this anagram:

“Sit! Pischon horti Aeden tuto fruar.”

(Let it be! May I safely enjoy the Pison of the garden of Eden.)

Or otherwise, the letters set differently:

“Durè sit thronus d. etrina Sophia.”

(May the throne of the Divine Sophia endure.)

But ye, who are possessors and understanders of this most great gift of God, are earnestly besought by our Lord—Who willeth not that pearls be cast unto swine—that with the utmost diligence ye forbid and guard this holy secret from the unworthy and from evil mockers, lest upon us should fall in heaps the curses of the Magi and of the most ancient Philosophers, of which the great Rosarius maketh mention in these words:

“In the art of our Magistery nothing is concealed by the Philosophers, except the secret of the Art, which it is not lawful for any to reveal: for if it were done, he should be accursed, and fall under the indignation of the Lord, and die of apoplexy.”

Likewise Lullius, in the Theoria Testamenti, cap. 6:

“I swear unto thee upon my soul, that if thou revealest it, thou art damned: for if thou shouldest reveal in a few words that which God hath formed in a long time, in the day of great judgment thou shalt be condemned, nor should the crime of high treason against Majesty be forgiven thee,” &c.

And Basil Valentine in his Testament:

“This would be the most grievous sin, and the greatest of all, if an unworthy man should learn it from thee,” &c.

Likewise Aristotle, in his Epistle to Alexander:

“If (namely by my open writing) this ultimate good and divine secret should come unto the unworthy, then should I indeed be a transgressor of divine grace, a defrauder of the heavenly seal, and of the hidden revelation: therefore under witness of the Divine judgment,” &c.

And Hermes:

“Lest the wicked should thereby become powerful unto sins, and the Philosophers be bound to give account of their sins.”

On the Third Principle of Mineral Things

Chapter 1.

The condition and quality of the Salt of Nature.

Salt—by the ancients veiled in silence, but by Johann Isaac Hollandus, Basilius Valentinus, and Paracelsus acknowledged and declared—as it is the third principle of all things (thus we continue the order of our Father, who gave the first place to Mercury, the second to Sulphur, and reserved the third for Salt; otherwise, none of the principles is either first or last, for they are of one and the same origin and coequal beginning)—even so was it from the beginning the third initial Ens of minerals, bearing within itself the two other Primordials, namely Mercury and Sulphur, and in its birth holdeth the place of mother or womb, binding the impression of Saturn, whereby metals obtain body.

Now this Salt is threefold. First, the central salt, which in the centre of the elements, by the qualification of the stars, through the Spirit of the World, without any cessation is generated, and is ruled in the Philosophical Sea by the rays of Sun and Moon. Second, the spermatic salt, as it were the dwelling of the invisible seed, which by its gentle natural heat, through putrefaction, giveth forth form and its own vegetability; so long as that most volatile invisible seed be not dissipated and destroyed by outward heat or any contrary violent accident, for then nothing more can grow therefrom. The third salt is the ultimate matter of all things, found in them after their destruction, and remaining as survivor.

This threefold salt therefore, at the very first moment of Creation, when God spake Fiat, had its origin, and its existence was made out of nothing. For the original chaos of the World was nothing else but a certain salty darkness, a cloud or mist of the abyss, which, by the Word, the Logos, was concentrated from the invisible, and by the calling of God came forth as a first material being, or Hyle: existing actually neither dry nor moist, nor thick nor thin, nor bright nor dark, nor hot nor cold, nor hard nor soft, but only a mixed Chaos, from which afterwards all things that are were made and separated. But we pass over these matters here, and treat only of our Salt, namely the third Principle of minerals, which also is the beginning of the Philosophical Work.

Yet let the Reader, who would draw profit and apprehend our meaning, before all things most diligently peruse the writings of other true Philosophers, and chiefly those of Sendivogius above cited, and from them fundamentally learn the generation and first stars of the metals, which all proceed from one root. For he who exactly knoweth the generation of metals, knoweth also their melioration and transmutation. Having thus known the fountain of our Salt, further instruction shall here be given, how, after devout prayer, and the blessing of Divine grace, there may from it be obtained the precious and snowy Salt, and the living water of paradise be drawn, and with it the Philosophical Tincture prepared, which is the highest treasure in this life, and the gift of supreme nobility, bestowed by God upon the wise.

Rhymes

Pray God for wisdom, clemency, and grace to be given thee,

Whereby this art is attained.

Let no other thing occupy thy imagination,

Save only the Hyle of the Philosophers.

In its saline fountain of our Sun and Moon

Thou shalt find the treasure of the Son of the Sun.

Chapter 2.

Where is our Salt to be sought?

Even as our Azoth is the seed of all metals, and by Nature is constituted and compounded into equal elemental proportion, temperament, and concord of the seven planets; so also solely in it, and in no other thing of the world, must the strongest strength of the strong be sought and expected. For in the whole Nature of things there is but one thing, from which our Art professeth itself to be true, and in that alone it wholly consisteth; and if not from it, then it is the Stone and not the Stone. It is called the Stone by similitude: first, because its mine, taken at the beginning from the caverns of the earth, is indeed a stone, a hard and dry subject, which, like a stone, may be broken and ground. Secondly, because, after the destruction of its former shape (which, like foul sulphur, must be taken away) and after division into its parts (compounded and gathered by Nature herself), it must be reduced into one essence, and by gentle digestion into a Stone unburnable by fire and most certain according to Nature. If therefore thou knowest what thou must seek, then already thou knowest our Stone also; for whatsoever thou desirest to generate or bring forth, of the same thou must needs have the seed.

Now all Philosophers do not only testify, but reason itself convinceth, that that metallic tincture is nothing else but gold digested to the supreme degree of maturity. For if a golden tincture could be made out of any other thing than the entity of gold, it would follow that such a tincture should also tinge all other things in like manner as metals are wont to be tinged, which it doth not; but only metallic Mercury, as tinged and perfected, is actually gold or silver, which before was but in potency, and this in such manner: when the one Mercury of the metals (in whose womb its agent and patient cohabiting together is called Hermaphrodite, and digested to pure fixed whiteness becometh silver, but to redness gold) is taken in its spermatic immaturity, and only that homogeneous nature is by coction matured or fixed, whose final sign is that it glow intensely red, and the whole mass neither smoke nor exhale the least vapour in the flame of any fire, nor become lighter in weight; and afterwards again be dissolved in the fresh menstruum of the world, that the most fixed portion flowing through all may be received into its belly, where such fixed sulphur is reduced into far easier solubility, and the volatile sulphur, by the great magnetic heat of the fixed, is in like manner soon matured, &c.

For one Mercurial nature will not leave the other, until at last thou seest such red or white gold, or rather mature, fixed, and perfect Antimony, congealing in cold, but in heat melting most easily like wax, and soluble in any liquor, and distributing itself through all its parts, colouring it throughout, just as a little saffron colour eth a large quantity of water. This fixed liquefiable nature, coming into metals in flux, will flow together with them as water, in the greatest heat, through the least parts, and the fixed water will retain the volatile throughout, and defend it from combustion. The twofold heat of fire and of sulphur will act so sharply, that imperfect Mercury cannot resist, but after scarce half an hour, with the emission of a certain crackling or crepitation, will show itself overcome, its inmost brought forth outward, and the whole converted into pure perfect metal.

Whosoever therefore hath ever had either the Philosophical or any particular tincture, hath had it only from this foundation. Thus that great Philosopher, our fellow-German Basilius Valentinus, born in Upper Alsace (who lived in my fatherland a century ago), gave faithful testimony in his Triumphal Chariot, concerning various tinctures obtained from this basis, writing thus:

“The Stone of Fire (concocted from Antimony) doth not tinge universally, as doth the Philosophers’ Stone which is prepared from the essence of the Sun: by no means. For it is not endued with such virtue to effect it; but only tingeth particularly, namely the Moon into the Sun, besides tin and lead. Mars and Venus indeed it leaveth out, save so far as may be drawn forth by separation; nor can one part of it transmute more than five parts, that it should remain fixed in Saturn and Antimony itself, in quartation and in burning. Whereas, contrariwise, that true and most ancient great Stone of the Philosophers is able to effect infinitely. Likewise in the augmentation of itself, the Stone of Fire cannot so greatly be exalted, though it is itself pure and fixed gold.”

Moreover, let the Reader note that not of one kind only are there Stones that tinge particularly; for all fixed tincting powders are called stones, yet one always tingeth more powerfully and deeply than another. Of which kind is first the Philosophers’ Stone, which holdeth the highest place of all; next followeth the Tincture of the Sun and of the Moon to red and to white; then the tincture of Vitriol and of Venus, and also the tincture of Mars—both of which contain the tincture of the Sun in themselves, if only they first be brought to persevering fixation. After these cometh the tincture of Jupiter and of Saturn, to coagulate Mercury; lastly the tincture of Mercury itself. This then is the difference and manifold diversity of stones and tinctures. Yet all are begotten from one seed and from one only original mother, from which likewise the genuine universal work hath flowed forth; beyond which no other metallic tincture can ever be found. As for all other stones, noble or ignoble, they move me not at present, nor will I say or write aught of them, seeing they have no power beyond medicine. In like manner of animal and vegetable stones I shall now make no mention, for they are ordained only to medical use, nor can they effect any metallic work, nor yield any power of themselves; whereas the virtue and potency of them all, both mineral, vegetable, and animal stones, are altogether united in the Philosophical Stone.

Salts indeed have no power at all of tinging, but only serve as keys for the preparation of the stones; otherwise by themselves they can do nothing, save only as concerning the salts of the metals and minerals (whereof I now speak another thing, if thou wilt rightly perceive what distinction I would have understood between the salts of minerals). These must by no means be omitted nor rejected with regard to tinctures; for in them we cannot lack in composition, since in these is found that most excellent treasure, whence all fixation with permanence hath its origin, and the true and only foundation. Thus far Basilius Valentinus.

In this root therefore consisteth all Philosophical truth, and he who exactly knoweth this foundation—that which is above being most inwardly the same as that which is below, and vice versa—unto him the use and operation of the Philosophical key shall not be hidden, which by its bitter ponticity calcines and resolidifies all things. Albeit by such resolidification of perfect bodies only that same sperm would be found, which long since may be had prepared by Nature, and there were no need to reduce a compact body, but rather that this sperm, as given soft and immature by Nature, should be carried on to maturity.

Be thou therefore wholly intent upon this primitive metallic subject, which Nature indeed hath fashioned into metallic form, yet left immature and incomplete, in whose soft mountain thou mayest the more easily dig a pit, and thence obtain pure spring water, encompassed about with its own fountain, which alone and no other wave is apt and born to be formed with its proper metallic flour and solar ferment into a paste, and concocted into ambrosia. And though our Stone be of one kind in all the seven planets, as the philosophers say, the poor (namely the five imperfect metals) as well as the rich (that is, the two perfect metals) possessing it, yet it is found best in the fresh and untouched receptacle of Saturn. Of this, namely, whose son the whole world without mystery beholdeth day and night before its eyes, and by seeing useth it, yet no spectacles of the eyes will persuade them to perceive, or at least to believe, that this greatest arcanum is therein. All philosophers affirming and swearing that this is the ark of their arcanums, and retaineth within itself the inward and hidden spirit of the Sun.

Clearer our vitriolated egg we cannot describe, so long as there be known the manifold progeny of Saturn, namely: triumphant Stibium, Bismuth melting at a candle, Cobalt blacker than lead and iron, Lead the tryer, Litharge serving painters, Zinc colouring, showing itself in diverse marvellous ways like unto Mercury itself, Antimony from the air both calcinable and vitrifying, &c. And though that inevitable cook of mankind, serene Vulcan, sprung of black parents as of dark flint and steel, hath not been unable to prepare excellent medicines from each of the aforesaid, yet from them all our Mercury differeth as volatile.

Verse

There is a Stone and not a Stone,

In which the whole Art consisteth.

Nature made it so,

But hath not yet brought it to perfection.

Thou shalt not find it growing upon the earth;

It groweth only in the caverns of the mountains.

On it dependeth all this Art.

For he who possesseth the vapour of this thing,

The golden splendour of the red Lion,

Pure and clear Mercury,

And in this knoweth the red Sulphur

With such an one is the whole foundation.

Chapter 3.

On Solution

Now that the cold Northern Monarchy is upon us, which will soon be followed by the calcination of the World, it were most just also to begin the philosophical calcination, or solution (which is the prince of the monarchy of Chemistry), wholly to be unveiled unto the World. For once it be known, it would not be difficult for many to handle the golden art, and within a short time to obtain dominion over all the treasures of Nature. This would be the sole means to banish from human borders that accursed hunger for gold, which now (alas, alas, with sorrow!) seizeth almost all the inhabitants of the earth to their ruin, and to cast down the golden calf, which great and small do now adore, in honour of God. But since such things, with other still hidden arcana, pertain unto Elias the Artist—who shall soon appear, as long ago Paracelsus foretold, namely that a third part of the world should perish by the sword, another by plague and famine, and a third scarce remain; even the orders (that is, of the seven-headed beast) shall perish and be utterly taken away from the world—then (saith he) shall all things be restored into their place and entirety, and it shall be a golden age, when man shall attain unto sound understanding, and shall live after the manner of man, &c.

Wherefore such things are reserved to that person whom God hath crowned for it. Meanwhile, we write those things by which at this time we may profit the seeker of the art, and say, according to all Philosophers, that true solution is the key of this whole art, which also is threefold: first, of the crude body; second, of the philosophical earth; and third, in multiplication. And since a thing calcined is more easily dissolved than one not calcined, it is necessary that calcination and destruction of the sulphureous impurity and of the combustible stench should go before; and if somewhat of helpful waters or menstruums be applied, it must afterwards wholly depart, so that nothing heterogeneous at all may remain. Withal this supreme caution must be had, lest perchance by excessive outward heat, or some other hurtful accident, the internal generative and multiplicative virtue of the Stone be slain, burned, or put to flight; concerning which the Philosophers give serious admonition, saying in the Turba: “In its purification, above all take heed and have care, lest the active virtue be burned up or suffocated; for no seed ever groweth or multiplieth when its generative force is taken away by outward heat.” But when thou hast the sperm, thou shalt afterwards finish the whole labour by gentle cooking. For first from the magnesia we gather the sperm, gathered we putrefy, putrefied we dissolve, dissolved we divide, divided we purify, purified we unite, and so the work is fulfilled. And as the author of the most ancient Duel, or Dialogue of the Stone with Gold and common Mercury, saith: “By Almighty God, and for the salvation of my soul, I testify and make known to you seekers of this most excellent art, from a faithful mind and from compassion of long investigation, that all our work consisteth but of one thing, and is seen in itself, nor needeth more than solution and reimpression. Therefore it must be done without any foreign thing, even as ice placed in a dry vessel over fire is made water by heat. So likewise our Stone needeth not more than the aid of the artist by his manual operation, and the natural fire. By itself alone it cannot, though it should lie for ever in the earth. Wherefore it must be helped, yet by no foreign or contrary things, but rather as corn is given us in the fields by God, and we must grind and pound it that bread may be made: so here. God created for us this brass, which we only receive; its crude and gross body we destroy, the good inner kernel we gather, the superfluity we remove, and from poison we prepare medicine.”

Thou seest then that without solution thou wilt accomplish nothing. For when the Saturnine Stone hath bound up the Mercurial water, and made it stiff in its bonds, it must needs by gentle heat putrefy within itself, and be resolved into the primordial humour, whereby the invisible, incomprehensible, and tinging spirit—which is the pure fire of gold—being shut up and imprisoned in the inmost bowels of the congealed salt, shall be brought forth; and the grossness of the body, by regeneration, shall likewise be subtilized, and indivisibly folded together with the spirit.

Therefore solve the Stone duly,

and in no sophistical manner,

but rather according to the mind of the wise,

with no corrosive employed.

For there is no water anywhere

that can dissolve our Stone,

save only one most pure and limpid little fountain,

springing forth of its own accord,

which is the water fit for solution,

but hidden from almost all.

Growing warm of itself, it becometh the cause

that the Stone sweateth tears.

A slow outward heat helpeth it,

bear this well in memory.

One thing more I will reveal to thee:

unless thou seest black smoke beneath,

and whiteness above,

thy work is wrongly performed,

and thou hast dissolved the Stone amiss.

By this sign thou mayest instantly discern;

but if thou proceed aright,

there appeareth to thee a black mist,

which straightway sinketh to the bottom,

while the spirit taketh on whiteness.

Chapter 4.

How our Salt is divided into the Four Elements, according to the Philosophical Understanding

Since our Stone is outwardly moist and cold, but its inward heat is a dry oil, or sulphur, and a living tincture, with which the quinta essentia must be joined in a natural manner, it is necessary that thou separate these contrary qualities from one another, and reduce them into true concord. This our separation accomplisheth, which in the Philosophical Scale is called the separation or purification of the watery vapour or liquor from the dark dregs, the levigation of rarity, the extraction of gross parts, the division of things joined, the production of Principles, the segregation of homogeneity. And it must be done in due baths, &c.

But the elements must first be digested in their bosom, because without putrefaction the spirit cannot be separated from the body. And it alone is that which subtilizeth, and bringeth forth volatility. When, however, it is sufficiently digested so that it can be separated, being separated it is the better clarified, and becometh argent vive, having the appearance of a clear water. Divide therefore the Stone into two distinct parts of the Four Elements, namely into the volatile and the fixed. That which is volatile is Water and Air; that which is fixed is Earth and Fire. Among these only Earth and Water are discerned, but not Fire and Air. And these are the two Mercurial substances, or the double Mercury of Trevisan, distinguished by the Philosophers in the Turba under these names:

1. Volatile

2. Argent vive

3. The Superior

4. Water

5. Woman

6. Queen

7. White Wife

8. Sister

9. Beya

10. Volatile Sulphur

11. Vulture

12. Living

13. Water of Life

14. Cold and Moist

15. Soul or Spirit

16. Dragon’s Tail

17. Heaven

18. Its Sweat

19. Sharpest Vinegar

20. White Smoke

21. Black Mists

1. Fixed

2. Sulphur

3. The Inferior

4. Earth

5. Man

6. King

7. Ruddy (Red) Servant

8. Brother

9. Gabrius

10. Fixed Sulphur

11. Toad

12. Dead

13. Blacker than the Blackest Black

14. Hot and Dry

15. Body

16. Dragon devouring its own tail

17. Earth

18. Ashes

19. Brass or Sulphur

20. Black Smoke

21. The bodies of those things from which they proceeded, &c.

In the higher spiritual volatile part is the life of the dead earth; and in the lower fixed portion of earth is the nourishing ferment which fixeth the Stone. These two are of one root, and must both be united in the form of water. Take therefore the earth and calcine it in moist warmth of horse-dung until it whiten and appear fat; this is Sulphur not burning, which by greater digestion can be made red sulphur. But it must first be white before it can be red; for from black there is no passage unto red save through the middle, namely whiteness. And if whiteness be present in the vessel, then without doubt redness is hidden in it. Therefore it must not be drawn out, but only cooked until it redden.

Verses

The gold of the wise is not that common gold,

But a certain water, clear and pure,

Over which the Spirit of the Lord did move,

And every being hath thence its life.

Therefore our gold is altogether made spiritual,

Carried through the alembic by the spirit.

Its earth remaineth black,

Which before appeared not,

And now dissolveth itself,

And becometh again a thick water,

Desiring noble life,

That it may be restored thereto.

For by thirst it dissolveth and breaketh itself,

And this greatly helpeth it.

For unless it became water and oil,

The spirit and soul could not

Be mingled with it, as now it happeneth,

So that one thing is constituted from them,

Arising unto full perfection,

So firmly bound together,

That no separation is henceforth possible.

Chapter 5.

The Preparation of Diana, white with snowy brightness

The Philosophers call our Salt the Seat of Wisdom, nor without cause; for it is altogether full of divine virtues and miracles, and from it may all the colours of the world be unfolded. Externally, indeed, it is especially white with snowy whiteness, but inwardly it holdeth a sanguine redness, being at the same time filled with the sweetest savour, with life-giving virtue, and with celestial tincture. Yet all these are not of the Salt’s own property, seeing that it giveth only acridity and the bond of coagulation. But its internal heat is pure, simple, essential fire, and the light of Nature, and a beautiful, pellucid oil, of such sweetness that no sugar or honey may equal it, inasmuch as it may be wholly separated from other properties. Moreover, the invisible spirit dwelling therein, by its vehemence of penetration, is equal to the irresistible might of lightning, most powerfully piercing. From these therefore, united together, and fixed into an incombustible essence, ariseth the most potent Tincture, which, like the fiercest thunderbolt, doth in the twinkling of an eye pervade bodies, and whatsoever it findeth contrary to the point of life, it forthwith expelleth. By this means metals are transmuted or tinged into gold, for they were already gold before, sprung from the one entity of gold; corrupted only with leprosy and sevenfold disease, derived from the curse and wrath of God. And unless they had been gold from the beginning, never could the Tincture transmute them into gold; just as man is not gold, even if he receive the Tincture, yet it expelleth every evil of his body. Careful anatomy of the metals also showeth that inwardly they are a golden entity, but outwardly encompassed with matter and execration.

First, they possess an immoveable, gross, and hard substance from this accursed earth, to wit, their stony thickness in the mine. Secondly, a deadly stinking water. Thirdly, in this water a certain mortified earth. And fourthly, a destroying, furious, venomous quality. All these maledictions of heterogeneity being separated from the metals, there is found also the noble golden entity—our blessed Salt—which the Philosophers have commended unto us in these words: “Draw forth the Salt from the metals without corrosion and violence, and it will give unto thee white and red.” Likewise: “All the secret consisteth in Salt, from which is composed our perfect Elixir.”

But how hidden the reason of instituting and attaining such a thing is, is plain from this—that even unto this day the world hath not fully known this science, and even now scarce a thousandth part understandeth what to think of the marvellous preaching of the Sages concerning one and the same single thing, which is nought else but natural genuine gold, and yet is most vile, and to be found cast in the way: a most precious price, and yet dung; a fire burning stronger than any fire, and yet cold; a water most pure in washing, and yet dry; an iron hammer beating into impalpable atoms, and yet soft as water; a flame most extreme in burning to ashes, and yet moist; snow snowy, and yet coctile and wholly condensable; a bird flying on the mountain-tops, and yet a fish; a virgin undefiled and yet bearing, and abounding with milk; the rays of Sun and Moon, and the fire of sulphur, and yet ice congealed; a tree burned, and yet in burning flowering and bearing an immense abundance of fruit; a mother bringing forth, and yet nought but a man, and the converse; a metal heavy, and yet a feather, or feathery alum; a feather borne by the wind, and yet heavier than metals; a poison deadlier than the basilisk, and yet expelling all diseases, &c.

These and the like contradictions, which yet are the proper names of our Stone, altogether blind the ignorant, so that innumerable deny its truth, though in other things they claim to themselves all the ingenuity of the world—believing Aristotle alone more than the countless multitude of most weighty Authors who for many ages verified and described such things, declaring that of their words and these of their deeds they should render account before the last judgment. Yet this availeth nothing: the possessors of knowledge are ever despised, and that not without the heavy judgment of God, Who, the better gift He putteth into any vessel, the more foolishly causeth it to appear in its own kind, that it may the sooner be despised and rejected by the unworthy to their own perdition. But the sons of prudence observe with fear this mode of divine ordinance, weighing how the parabolic style of Scripture, both most holy and of all other wise men, signifieth far otherwise than the dead letter would show; wherefore, according to the command of the first Psalm, they meditate therein day and night, and with anxious mind seek the pearl, until by prayer and labour they find it.

For if God so evidently denieth this Stone of earthly miracles to all evil men, seeing that it is at least a small picture of that most holy heavenly Corner-Stone, what thinkest thou of the having of the very authentic One, whom all angels and archangels adore? And yet without difficulty every one that is regenerate may promise it unto himself, if only he cast away the stinking scoria, and in no wise contend, but enter through the narrow gate into the kingdom of heaven, following all the saints of the Old and New Testament.

But we know fundamentally that all Theology and Philosophy without the incombustible oil are vain. For even as the five imperfect metals perish in the trial of fire, unless the incombustible oil (as the Philosophers call the Stone) do tinge and bring them to perfection: so also those five foolish virgins, not having true oil in their lamps, shall perish at the coming of the King the Bridegroom. For the King (as is read in Matthew 25:41–43) shall set those who lack the oil of charity or mercy on His left hand, and shall say unto them: “Depart from me, ye cursed, into everlasting fire, prepared for the devil and his angels. For I was hungry and ye gave me not to eat; I was thirsty and ye gave me not to drink; I was a stranger and ye took me not in; naked, and ye clothed me not; sick and in prison, and ye visited me not.”

On the other hand, even as they who diligently study to understand the wonders of God, and ardently seek illumination from the Father of Lights, do at last receive the Spirit of Divine Wisdom, which leadeth them into all truth, and by living faith uniteth them with that victorious Lion of the tribe of Judah, Who alone openeth and looseth the book of regeneration, sealed with seven seals, in every faithful man—so that there is born in him that Lamb which from the beginning was slain, and Who alone is Lord of Lords, crucifying by His cross of humility and meekness the old Adam unto death, and regenerating the new man from the seed of the Word of God.

So likewise is this type beheld in the philosophical work of regeneration, where the green Lion alone closeth and openeth the seven indissoluble seals of the seven metallic spirits, and cruciateth the bodies unto perfection, by the long-suffering and meek patience of the artist. For such an one is likewise the Lamb, to whom, and to no other, the seven seals of Nature shall be opened.

O ye sons of light, who in the power of the Lamb of God are victorious, all things that God ever created shall be for your temporal and eternal felicity. For such promise hath been made from the living mouth of our Lord Jesus Christ, twice eight times in succession, in Matthew 5, in the Apocalypse 2 and 21, in these words.

1. Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven.

To the victor I will grant to eat of that tree of life, which is in the midst of the paradise of God.

2. Blessed are they that mourn, for they shall receive comfort.

He that overcometh shall not be hurt of the second death.

3. Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth by right.

To the victor I will grant to eat of that hidden manna, and I will give him a white stone, and in the stone a new name written, which no man knoweth save he that receiveth it.

4. Blessed are they that hunger and thirst after righteousness, for they shall be filled.

If any one overcome and keep my works unto the end, I will give him power over the nations, and he shall rule them with a rod of iron, and as the vessels of a potter they shall be broken to shivers, even as I received of my Father; and I will give him the morning star.

5. Blessed are the merciful, for mercy shall be shown unto them.

He that overcometh shall be clothed in white garments, and I will never blot out his name from the book of life, but will confess his name before my Father and before His angels.

6. Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.

He that overcometh I will make a pillar in the temple of my God, and he shall go out no more; and I will write upon him the name of my God, and the name of the city of my God, the new Jerusalem, which cometh down from heaven from my God, and my new name.

7. Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called the children of God.

To the victor I will grant to sit with me in my throne, even as I also overcame, and sit with my Father in His throne.

8. Blessed are they who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven.

The victor shall inherit all things, and I will be his God, and he shall be my son.

Let us therefore, O brethren, by the grace of our merciful Lord, take unto ourselves a laborious soul, to fight the good fight; for no man shall be crowned save he that hath striven lawfully. Even so God selleth His temporal gifts at least by sweat and toil; and the Philosophers with Hermes bear witness that they could not spare themselves labour in acquiring the blessed Diana, and the joyful Lunar Lethea, as each may well conjecture.

For since our Salt is at the beginning an earthy subject—heavy, rough, impure, chaotic, gluey, slimy, and cloudy, an aqueous body—it must of necessity be dissolved, and separated from its impurity, and from all terrestrial, watery, and venomous accidents, and from its dense shadow; purified and sublimed to the utmost, so that the crystalline Salt of the metals, purged from all foul blackness and corruption, may be had in utmost purity, clarified to the highest degree, white as snow, and flowing and melting like wax.

Salt is the sole and only Key:

Without which our Art can in no wise be true.

Although this Salt (to make thee certain)

Hath not at first the appearance of salt,

Nevertheless it is salt, and without doubt

At its first inception altogether black and foul.

In the progress of the work it will also

Resemble the coagulum of blood,

And at last shall become wholly white and clear,

By dissolving and coagulating itself.

Chapter 6.

On the Marriage of the Ruddy Servant with the White Woman

Many there are who seem to themselves to have knowledge of the preparation of the Philosophical Tincture. But when examined by our ruddy servant, it can scarcely be believed how few, and what a very small number, endure such a trial. For where is the book that giveth sufficient instruction on this matter? The Philosophers keep silence and will it hidden, as likewise did our beloved father, leaving to the seekers, by way of revelation, only these few words: “One single thing, mixed with the Philosophical water.” And without doubt this hath caused no small labour to certain philosophers, before they could sail past this Syrtis, at the very first salutation of the work.

A notable example of this was related to us by the disciple of the Author of the Arca Apretæ — The Open Ark commonly called the Greater and Lesser Farmer —who possesseth by his own hand the manuscripts of that teacher (now resting in God), and hath perfectly known the whole art of philosophy for thirty years. He told how this master of his fared at this stage: when first he came hither, the two sulphurs would by no means come together or be commixed, but always the Sun swam above the Moon. This caused him great lamentation, and wearisome return to a new journey, that he might learn this point from some possible possessor of the Stone, which at length he obtained, and whose experience no philosopher hath yet surpassed. For he trod the nearest path of the art, to wit, of finishing the Stone in thirty days, whereas others must needs keep it cooking first for seven, afterwards for ten continuous months. This we note for those who, by imagination and self-persuasion, believe themselves philosophers, yet have not attempted the due manual operation, that they may consider whether aught be lacking to themselves. For before this passage, not rarely are the presumptuous artificers compelled to lay aside their Daedalean wings.

Moreover, some are found—even among those who are doctors and men of very great learning—who are fully persuaded that our digested ruddy servant must needs be drawn from nothing else but vulgar gold, by Mercurial water. But this error the most experienced Author of the ancient Duel of the Chemists long ago exposed, when, in the person of the Stone, he uttered these words: “Some have come so far with me that they knew how to extract my tinging spirit, mixing it with other metals and minerals, and by many labours bringing me so far that I yielded somewhat of my virtues and powers into the metals nearest and most akin to me. But had the artificers cared for my proper wife, and joined me with her, I could have tinged a thousandfold more.”

In truth, as concerning our conjunction, there are two ways of joining: one moist, the other dry. In the former, the Sun hath three parts of his water, and his wife nine parts, or even two to seven. And as the seed of man is at one time and in one act cast into the womb, and afterwards in a moment is closed until the bringing forth of the fruit, so likewise in our work we join two waters: the sulphur of gold, and also its Mercury; the soul and the body; the Sun and the Moon; the man and the woman; the two females; the two argents vive. From these ariseth the living Mercury, and from him the Philosophers’ Stone.

Verses

After the earth hath been rightly prepared

To imbibe its own moisture,

Then take together spirit, soul, and life,

And bring them into this earth.

For what is earth without seed?

Or a body without a soul?

Mark well, and observe:

Mercury is returned

Unto his mother, whence he came.

Cast him into her again, and it shall be thine.

The seed shall dissolve the earth,

And the earth shall coagulate the seed.

Chapter 7.

On the Degrees of Fire

In the concoction of our Salt, the outward heat of the first operation is called boiling, and is done in moisture; but the warmth of the second operation is accomplished in dryness, and is called roasting. This twofold fire the philosophers thus inculcate unto us: We must boil and roast the Stone.

That blessed work of ours is directed according to the constitution of the four parts of the year: the first part of winter is cold and moist; the second, of spring, is warm and moist; the third pertaineth unto the very hot and drying summer; the fourth unto autumn, appointed for the gathering of fruits.

The first regimen of fire must be like unto the heat of the hen brooding upon her eggs to bring forth chicks; or like unto the stomach digesting food and nourishing the body; or like unto the warmth of dung; or of the Sun being in Aries. Such warmth lasteth until blackness appear, and also until it be changed into whiteness. But if such regimen be not observed, and the matter be overheated, then the desired crow’s head shall not be obtained, but instead it will produce a sudden and quickly vanishing redness, unhappily like the wild poppy, or else a reddish oil floating above, or again the matter will begin to sublime. In such cases it is necessary to take up the composition anew, to dissolve it, and imbibe it with our Virgin’s milk, and afterwards to commit it again to the fire, with more watchful caution, until such defects no longer appear.

After whiteness hath appeared, the fire must be increased, until the Stone be wholly dried. This degree is likened unto the heat of the Sun passing from Taurus into Gemini. But when the Stone is dried, the fire must yet carefully be strengthened, until its redness be perfected; which heat is like unto the Sun abiding in Leo.

Verses

Be most attentive to the counsels,

Destroying with gentle fire set forth;

And so mayest thou promise unto thyself prosperity,

And be made at last partaker of this treasure.

I am already the fire of vapour,

According to the intimate understanding of the wise,

Which is not elemental,

Nor material or semblant,

But rather the dry water of Mercury.

This fire is supernatural,

Essential, heavenly, and pure,

In which the Sun and Moon are joined together.

Govern it by the moderation of outward fire,

And bring our work unto its end.

Chapter 8.

On the Miraculous Efficacy of our Saline-Aquarian Stone

Whosoever hath obtained from the Father of Lights this gracious indulgence—that unto him in this life should be granted that treasure more precious than all preciousness, the Philosophers’ Stone—such an one may not only be assured that he possesseth a treasure which the whole world, with all its princes dwelling round about, could not repay, but also holdeth therein the most evident token of Divine Love toward him, and the pledge that henceforth he shall have Wisdom of God, whose gift this is, as his spouse, and with her an eternal marriage, equal and abiding. Which union of heavenly matrimony we from our heart beseech for every Christian, since it is the centre of all treasures.

Even King Solomon testifieth the same, Wisdom vii: “I preferred Wisdom before kingdoms and principalities, and esteemed riches as nothing in comparison with her. I likened not unto her any precious stone, for all gold is but as a little sand before her, and silver in respect of her shall be counted as clay. I loved her above health and comeliness of body, and chose to have her for light; for her brightness never goeth out. And all good things came to me together with her, and innumerable riches were in her hands.”

First: In this Stone shineth forth the most holy God, One and Three, with His works of Creation, Redemption, Regeneration, and the state of future glorious beatitude.

Second: It expelleth and healeth all sicknesses, of whatsoever kind, unto the appointed term of life, where the spirit, as a quenched lamp, peacefully departeth, and passeth into the hand of God.

Third: It tincteth and transmuteth all metals into silver and gold, better than Nature herself produceth. By it also base stones, and the vilest crystal, may be changed into the noblest gems.

But when it is applied to transmute metals into gold, it must first be fermented with the best and most purified gold, else the excessive and supreme subtilty thereof cannot be borne by imperfect metals, but in projection would rather cause loss and damage. Moreover, the impure metals must themselves first be purged, if profit be looked for. To the red tincture the ferment of gold is added; to the white, the ferment of silver. One drachm sufficeth, and there is no need to buy gold or silver for fermentation; for with so small an addition it may afterwards be tinged more and more, until at last whole ships may be laden with the precious metal thus produced.

For if this medicine be also carried forward by multiplication, and be again dissolved and coagulated with its own water of white or red Mercury, out of which it was prepared, then its tinging virtue becometh ten times greater with every repetition—and this as often as one will repeat it.

Rosarius

“He who hath once perfected this art, though he should thereafter live a thousand thousand years, and feed four thousand men every day, yet should he never want.”

Aurora Consurgens

“This is the Daughter of the Wise, and there is given into her hand power, honour, virtue, and dominion, and the flowering crown of the kingdom is upon her head, glittering with the rays of seven shining stars, as a bride adorned for her husband. In her garments is written in golden letters, Greek, Barbarian, and Latin: I am the only daughter of the Wise, utterly unknown to fools. O happy therefore is science with the knowing, for whoso possesseth her hath an incomparable treasure, enriched before God, and honoured among men. For he is not made rich by usury and fraud, nor by false merchandise, nor by the oppression of the poor, as the rich men of the world now strive to do, but by industry and the labour of his hands.”

Therefore not without cause do the philosophers conclude with these two enigmas, concerning the White and the Red Tincture, or our Urim and Thummim.

LUNA

Here is born the holy Empress Augusta,

Whom the Masters call their daughter,

All with unanimous consent.

She multiplieth herself, and bringeth forth an innumerable offspring,

Existing in purity, immortality, and without any stain.

This Queen hateth death and misery,

And excelleth gold, silver, and noble gems,

And moreover all medicines, great and small.

Nothing in all the earth is comparable unto her.

For which cause let thanksgiving be offered

Unto the Divine Majesty in the holy heavens.

SOL

Here is risen the Emperor of all honours,

Never can one more exalted be born,

By any art, nor even by Nature herself,

Among all created creatures.

By the Philosophers he is called their Son,

Strong and mighty to give effect

Unto whatsoever man demandeth of him.

He imparteth health, steadfast perseverance,

Gold, silver, and precious stones,

Strength, youth fair and sincere.

He consumeth wrath, sorrow, poverty, and every languor.

O thrice blessed he who obtaineth such from God!

Recapitulation

Thou, my inquiring man, dear brother and little son, let us, I pray thee, begin again from the first, and repeat those things most needful for thee, if with desired success thou wouldst see thy search helped forward and prospered.

First, and before all things, thou must most firmly fix in thy memory and remembrance, that without the mercy of Jehovah thou art most miserable—yea, more wretched than the devil himself, to whom all the damned are subject—inasmuch as thou, being endowed with an immortal soul, must of necessity live on for all eternity, whether thou wilt or no: either with the Son of God among the saints in ineffable blessedness, or with God’s enemy, Satan, among the accursed, in unutterable torment. Therefore shalt thou revere Jehovah with thy whole heart, that He may save thee eternally, and walk with all thy strength in His commandments, that they may be unto thee the rule and norm of piety. For so the Saviour commanded: Seek ye first the kingdom of God, and all other things shall be added unto you.

Imitate herein our wise forerunners, and observe by what method they found favour with this dreadful Lord (before whom the Prophet Daniel saw thousands of thousands standing, and myriads upon myriads ministering), even as that most wise Solomon hath faithfully shewn us his own way, by which he obtained true Wisdom, in this most excellent and altogether imitable doctrine: