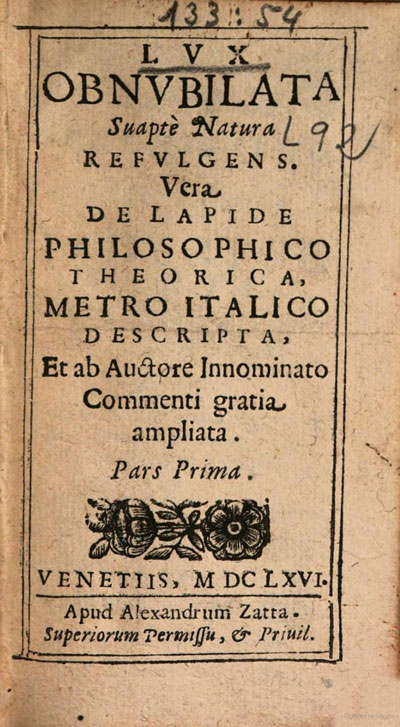

The Obscured Light, Shining by its Own Nature, Lux obnubilata, suapte natura refulgens

Buy me CoffeeTHE OBSCURED LIGHT, Shining by Its Own Nature.

Lux obnubilata, suapte natura refulgens. Vera de Lapide philosophico

TRUE THEORY

OF THE PHILOSOPHER’S STONE,

DESCRIBED IN ITALIAN VERSE,

AND ENLARGED FOR COMMENTARY

BY AN UNNAMED AUTHOR.

Part One.

Venice, 1666.

Printed by Alessandro Zatta,

With permission and privilege of the superiors.

TO THE MOST SERENE AND INVINCIBLE FREDERICK III

King of Denmark, Norway, the Wends and the Goths,

Duke of Schleswig, Holstein, Stormarn and Dithmarschen,

Count of Oldenburg and Delmenhorst.

Still the darkness lingered over the face of the abyss of my ignorance, when, by the impulse of the Divine Spirit, awakened from deadly slumber, I began to see the light: I greeted it, adored it, and loved it above all things.

It is not fitting for light to remain under the table, but to be placed on a mount so that it may shine for all.

Thus I intended to place this small flame of mine upon the golden candlestick of Your Majesty, so that those wandering afar in darkness, drawn by the brilliance of your resplendent diadem, might receive a spark of light to pursue the greater light.

The nature of an unceasing luminous flame is to communicate itself to others without diminishing itself; so too the innate capacity of your most glorious splendor will be to offer itself generously and remain unchanged in itself.

Certainly there is imminent danger that the lamp's flame be extinguished if exposed to disturbed airs; thus it must be protected by clear crystal so it may be shielded from the injuries of winds and other harms. Likewise, if I endeavor to expose this light of mine to the airs without restraint, there will be danger, from the harmful and pernicious breath of scoffers and smoke-blowers, of it being extinguished and scattered. Hence it is fitting for me to implore that under the shadow of your wings this light may safely shine and appear more splendid and illustrious.

Do not disdain, O King, the offering of this small gift in your name, but accept it and graciously illuminate it with the gratitude innate to your spirit; for every vow and offering has always been favorably received by the supreme minds of the gods, and they have never disdained the humility of the one who offers.

With a serene countenance, regard what we humbly present at the feet of Your Majesty, driven by the genial impulse of free devotion, and we pray that your most happy reign continue under ever-fortunate skies.

PREFACE TO THE READER

So many and such great volumes exist on the science of the Chemists, some published, others in manuscript, that I dare to say no science has had as many authors and teachers as the disciples of Hermes.

Happy the Father who had such sons! Glorious the Master who obtained such followers! Truly you deserve to be called the Master of Masters, if each one of your sons is worthy to be called a Master of all sciences. But just as not all books are the true offspring of their authors, not all are truthful; rather, some are mutilated, others corrupted, and—worse yet—adulterated. I believe this arises from the sting of envy and the impiety of those who, either due to the weakness of their intellect or by the just judgment of God, could not approach this table.

The tyrannies of the present age are so widespread that the age of men no longer deserves to be called human, but brutish. Yet nature—or the Artisan of nature—in the cloisters of His divine providence has always preserved some pious man.

Some remained immune to this poison; others hid from the serpent's death—those who, having seen the bronze serpent raised on the mountain, placed their hope in it and kept its sacred doctrines.

While I was still in the third lustrum of my green youth, I was, I know not by what instinct, driven with all effort to exercise my mind in the understanding of these books. But often, and again often, my mind, obscured by the greatness of that light, revealed how insufficient were the powers of my weak understanding to unravel the riddles of this learned Sphinx. Hence I cast aside the books, bade farewell to such reading many times, and more than once thought it erroneous even to wish to understand such things. But recovering my courage, supported by the help of God and hope, I spent twelve continuous years in such readings, day and nearly night, with all my strength, until I began to attempt whether I could reach the effect. I took the practice of the work in hand according to the theory I had conceived in mind; but now I obtained one resolution in spirit, now another, and always something obscure remained to my understanding.

I had two companions at different times, whose fellowship gave me greater occasion to study further and seek the truth, so that I might better argue or approve their opinions. For we were all blind, led only by the light of desire and some measure of reading. We tried; at first we found nothing; we knew something was lacking. Then I firmly began to conclude and to learn: to labor according to the literal sound of the letters is to waste riches and oil and effort, for only the possibility of nature and reason guides the blind and leads the wandering home.

Why sweat over such labors, when simple nature recognizes only one substance?

Why so many furnaces, fires, vessels, when nature uses one vessel, one fire, one furnace?

If the sound of letters and simple direction of the authors were sufficient, how many wiser—nay, the wisest in this science—would be found, who can hardly understand Latin.

Oh, how many are there who think themselves learned in this art, merely because they know how to perform a beautiful distillation, a careful sublimation, or calcination.

Oh, how many others are found who, with a single opinion formed in their thick heads from reading or what they call the direction of one Author, believe themselves most learned—and if the work fails to succeed according to their intent, they do not blame their ignorance, but a broken vessel or the management of the fire, hoping to find it by repeated effort.

Oh, how many think themselves masters because they hold a heap of many opinions in their brains, according to the capacity of their understanding, and believe they can teach others.

I knew a man who, not only many treatises, but entire volumes adorned with such learning and order, he held in his mind, so that I could scarcely believe greater expertise in this science could be attained. Yet, since he knew only the sound of the letters, he knew only the letters themselves. He did not know the work, nor did he truly even know it in theory—and never will he know it. He will always remain in his error, deceiving men, for he is completely astray from the truth, spending daily on particular tinctures (as he says) with endless expenses from those who believe in him too easily.

But this is no wonder, for when the one truth is hidden from someone, they try many paths and wander in the dark.

It is not enough to commit sayings to memory—they must be committed to the intellect and subjected to reasoning. Only the possibility of nature, as I said, must be observed, and her ways weighed on the scale of reason.

When a manuscript of learned verse in the vulgar Italian language, brought forth by an anonymous author, came into my hands, I took it upon myself in these times—when obscurity and darkness roam all around and nearly engulf the whole world—to bring light to light, and, with God as guide, to proclaim openly, as much as is permitted to be spoken, in a secret yet truthful style, what shall serve as commentary on that manuscript, and for its greater clarity and embellishment.

What kind of man the author of that work was has not yet become known to me, though he is recognized in an anagram. It is enough for me to know that he walked the straight path and met with the truth of nature—and though he confesses himself ignorant of the whole work, yet the end does not match the beginning; this feigned ignorance is a device of his doctrine.

As for me, dearest Reader, do not ask who I am. Know only that I wish to reveal the truth, and to bring forth greater things into the light hereafter than you believe or hope. May God grant me grace in life, and after the course of my life you shall know me.

Do not condemn the style and manner of speech or phrasing. Know for certain that this edition is untimely—so much so that you could hardly believe it. I am moved by a force that I could scarcely or unwillingly resist.

To utter such things in this age—I had not even dreamed. Yet let the will be done of Him who reigns and shall reign forever and ever. Farewell.

WE, THE REFORMERS OF THE

STUDIO OF PADUA,

Having seen, by the attestation of the Father Inquisitor, that in the book titled Lux Obnubilata Suapte Natura Refulgens. Vera de Lapide Philosophico Theorica there is nothing against the Holy Catholic Faith, and likewise, by testimony of our Secretary, nothing against Princes or good morals: we grant license for it to be printed, according to the regulations, etc.

Dated the day of April, 1665.

Zuane Donado, Reformer

Andrea Pisani, Procurator & Reformer

Angelo Nicolosi, Secretary

TO THE TRUE SAGE

One Discusses

THEORETICALLY

On the Composition

OF THE PHILOSOPHERS’ STONE

First Song

By

FRA MARCANTONIO CRASSELLAME CHINESE

1

From Nothing had emerged

The dark Chaos, a shapeless Mass,

At the first sound of the Almighty’s Word:

It seemed as though Disorder

Had given it birth, rather than

A God had been its Maker—so formless it was.

All things within it were idle,

And without a Dividing Spirit,

Each Element in it was enclosed,

Mixed together in confusion.

2

Who now could recount,

(Marvel!) how the Heavens, the Earth, and the Sea

Formed so light in being, so vast in mass?

Who can imagine how the Moon and Sun

Received light and motion above,

Or how below, all things took shape and state?

Who shall ever comprehend how all things

Received Name,

Spirit, quantity, law, and measure

From that impure and unordered Mass?

3

O you, Sons and Heirs

Of divine Hermes, to whom your father's Art

Makes Nature appear without any veil,

You alone—yes, only you—know

How Heaven and Earth were ever wrought

By the eternal Hand from undistinguished Chaos.

Your Great Work

Clearly shows

That God, in the very manner your Philosopher’s

Elixir is made, composed the All.

4

But I am not worthy

To draw with a weak pen such vast Parallels,

Still unskilled and but a Son of the Art.

Though surely my eye

Sees your pages strike the mark,

And though the prudent Iliasto is known to me:

Though the marvelous Compound

Is not hidden from me,

By which you have drawn out of potential

The purity of the Elements.

5

Though I understand

That your unknown Mercury is nothing else

But a living, innate Universal Spirit,

Descending from the Sun

In aerial vapor ever stirred

To fill the Earth’s empty Center;

Which then comes forth again

Among impure Salts, and grows

From volatile to fixed, and takes the form

Of radical moisture, shaping itself.

6

Though I know

That unless in Winter the Oval Vessel be sealed,

The noble vapor never settles in it,

And if lacking

The sharp eye of the Lynx or a skilled hand,

The white Infant dies at birth;

Then no longer fed

By its first humors,

Like man who in the womb feeds

On impure blood, then suckles milk in swaddling.

7

Though I know so much, still

Today I dare not venture into trial,

For others’ errors still leave me in doubt.

But if envious Cares

Have no place in your compassion,

Take from the Mind its doubtful heart.

If I have shown

Your Magistery plainly

In these my pages, then let it be

That your reply be an Act, not mere reading.

THAT THE MERCURY

AND THE GOLD OF THE COMMON PEOPLE

Are not the Gold and Mercury of the Philosophers,

And that in Philosophical Mercury is everything the Wise seek,

Touching on the practice of the First Operation,

Which the Experienced Worker must undertake.

Second Song

1.

How greatly are men deceived,

Unaware of the Hermetic School,

Who at the sound of the word

Apply themselves only with greedy intentions:

Thus to the vulgar names

Of quicksilver and gold

They set themselves to work,

And think that by slow fire

They can fix the fleeing silver.

2.

But if I open my mind to hidden meanings,

I clearly see

That both this and that

Lack the universal fire, which is the acting spirit.

A spirit that in violent

Flames of a vast furnace

Abandons and escapes

Every metal which, without living motion,

Outside its mine, is a motionless body.

3.

Hermes points to another Mercury, another Gold—

Mercury moist and warm,

Each hour more resistant to the fire.

Gold, which is all fire and all life.

Is there not an infinite difference

Between these and the vulgar ones?

Those are dead bodies, lacking spirit;

These are embodied spirits, and always alive.

4.

O great our Mercury, in you is gathered

Silver and gold extracted

From potential into act,

Mercury all Sun, Sun all Moon,

Three substances in one,

One which spreads into three.

O great marvel!

Mercury, Sulphur, and Salt, you comprehend,

Which in three substances are but one alone.

5.

But where is this rare Mercury

That, dissolved in Sulphur and Salt,

Becomes the radical moisture

Of metals, and the animated seed?

Ah! It is imprisoned

In so harsh a prison,

That even Nature herself

Cannot draw it from its dark cell

Unless the Master Art opens the path.

6.

What then does Art do? It ministers

To industrious Nature

With vaporous flame

It purges the path and leads to the prison.

Not with other guidance,

Nor with better means

Than with continuous heat

Does it aid Nature, so that she

May loosen the bonds of our Mercury.

7.

Yes, yes, this Mercury you enlightened souls

Must seek alone,

For in him alone you can

Find all that learned minds desire.

In him are already reduced

To near actual power

Both Moon and Sun; which, without

The vulgar gold and silver, united together,

Are the true seed of Silver and Gold.

8.

Yet every seed is seen to be useless

If uncorrupted and whole

It does not rot and turn black.

Generation is always preceded by corruption.

So Nature provides

In her living works,

And we who follow her,

If we do not wish in the end to produce monsters,

Must first blacken before we whiten.

THE INEXPERT ALCHEMISTS

To desist from their Sophistical Operations,

All contrary to those taught by true Philosophy

IN THE COMPOSITION

Of the Great Universal Medicine.

Third Song

1.

O you who, to fabricate gold by art,

Never tired, draw

Incessant flames from constant coal,

And your compounds in so many ways,

Now fix, now dissolve,

Now all dissolved, now partially congealed?

Then in some distant corner

With smoky butterflies, both night and day,

You watch around foolish fires.

2.

Cease now from your vain labors:

Let not blind hope

Gild your credulous thoughts with smoke.

Your works are but useless sweat,

Which, within your squalid room,

Only engrave hardship on your faces.

To what end such stubborn flames?

Not violent coal, not burning beeches

Do the Sages use for the Hermetic Stone.

3.

With the fire that works everything underground

Nature and Art labor—

For Art must only imitate Nature.

A fire that is vaporous, and not light,

That nourishes, and does not devour,

That is natural, and discovered by Art;

Dry, and yet it causes rain;

Moist, and yet it always dries; water that

Washes bodies but does not wet them.

4.

With such fire works the Art that follows

Infallible Nature,

Which, where Nature fails, supplements it.

Nature begins, Art finishes,

For only Art purifies

What Nature was incapable of purging.

Art is always wise,

Nature is simple; thus, if cunning

One does not smooth the paths, the other halts.

5.

So to what end so many substances

In retorts and alembics,

If there is but one matter, one fire?

The matter is one, and everywhere

The rich and poor possess it.

Unknown to all, yet present to all,

Abject to the wandering vulgar,

Who for mud at a vile price always sell

What is precious to the Philosopher who understands.

6.

Let keen minds seek this one despised Matter,

For in it is gathered all they desire.

In it are enclosed, united, Sun and Moon,

Not vulgar, not dead—

In it is enclosed the fire whence they have life.

It gives the fiery water,

It gives the fixed earth, it gives everything

That an instructed intellect ultimately needs.

7.

But you, without observing that one only

Is sufficient for the Philosopher,

Take more into your hands, ignorant Chemists.

He cooks in one single vessel under the Solar Rays

A vapor that blends itself.

You expose a thousand pastes to the fire!

Thus, while God composed everything from nothing,

You finally

Return all to the primitive Nothing.

8.

No soft gums or hard excrements,

No blood or human seed,

No sour grapes or herbal quintessences,

No sharp waters or corrosive salts,

No Roman vitriol,

Dry talcs or impure antimonies,

No sulphurs, no mercuries,

No vulgar metals does the expert Artist use

For the Great Work in the end.

9.

To what purpose such mixtures? The high science

Restricts all our mastery

To a single root.

This, which I have already clearly shown you—

Perhaps more than is lawful—

Contains two substances, and they have one essence.

Substances that in potential

Are silver and are gold, and in act

They become so, if we equal their weights.

10.

So they become silver and gold in act.

Indeed, once the volatile is made fixed

In golden sulphur.

O luminous Sulphur, animated Gold,

In you, kindled by the Sun,

I adore the concentrated operative virtue;

Sulphur, all treasure,

Foundation of the art, in which Nature

Refines the Gold, which ripens into Elixir.

PROEMIUM

There are many—indeed, almost all—who, upon hearing of the theory of the Philosophical Stone, immediately wrinkle their noses and disdainfully dismiss this treatise with scorn. But I ask, what impudence is it to pass judgment on things not known, and to intrude one’s own mustard into another’s field?

What the Philosopher’s Stone is must first be learned, and only afterward may its discussion be judged.

These are the same people who, seeing so many alchemists and those laboring in the art of alchemy, claiming they can make the Stone, observe them squandering both their own and others' wealth.

These are the same who, seeing so many deceptions, so many useless recipes, and hearing so many false promises, criticize the true art—not knowing that this is not the work of mere alchemists, but of Philosophers. For it is just as possible for these vulgar pseudo-philosophers to make the Stone as it is for them to produce a new sun in their home or trap the moon in a bottle. Indeed, to be a true Philosopher, one must know and truly understand the foundation of all nature.

They do not realize that the knowledge of the Philosopher’s Stone surpasses all teachings and all arts, however subtle. The difference is such that the work of nature is always more perfect, complete, and secure than any practice of the arts. In fact, if according to Aristotle's axiom, “nothing is in the intellect that was not first in the senses,” it will be true to say that whatever we comprehend through the senses, we understand only by the occasion given by nature.

For all the arts, their rudiments and first principles, have been learned from the work of nature—so much so that it would take too long to demonstrate this truth here, though it is sufficiently clear to any intelligent person who does not view with vulgar eyes. But let us not proceed further fruitlessly.

It must be generally known that the Philosopher’s Stone is nothing other than the radical moisture of the elements, which is found expanded in them, but in the Stone is united and purified from all foreign matter. Hence, it is no wonder that it can perform such great things, since it is well known that the life of animals, plants, and minerals consists in their radical moisture—this is an article of undoubted faith, and no one will ever deny it.

For if someone has oil stored in his house for putting into a lamp, who would be so foolish as to think that such a lamp could be extinguished by the depletion of the oil, which is its food for nourishing the fire? And if the weakening of the light comes from the depletion of oil, surely, by adding more oil, the light will resume its former brightness. In the same way, our life consists in our radical moisture, and the spark of life is carried and held within it. When this moisture is consumed, the vital light, freed from its bonds, escapes.

Thus, through nourishment, nature must replenish this moisture. But sometimes the natural heat, due to some accidents, becomes so weakened in its radical moisture that it can no longer resume new nourishment, and thus it languishes more and more, becomes oppressed, and ultimately perishes, abandoning the body in a dark death. If someone at that moment could supply oil—not enclosed in the excrement of food but separated from it and purified by every art—surely the fire of life would take it up and convert it into its own nature, thus flourishing again with its former brightness.

What use are remedies to a dead man? Not even the most perfect balsams can do anything. For it is nature, or the natural fire hidden in the body, which uses medicines to free and deliver itself from the disease or harmful humor, so that it may perform its task of life freely within its radical moisture. Therefore, through nourishment, food must be given that is fitting and restorative, and this fire will recover its former strength; otherwise, medicines are of no benefit, being merely an incitement to nature and not a restoration.

What good would it do a soldier, on the verge of death from blood loss due to a wound, to have his aggressive faculties stirred by trumpets and drums to fight off enemies and bear the labors of Mars? Truly, it would be of no help—indeed, more harmful, making him faint with terror. So also in our case: to stir nature through medicines when it is weakened by the loss or suffocation of radical moisture is dangerous and often useless. But if someone could restore its former strength and increase its radical moisture through suitable administration, then nature would free itself from harmful waste and malignant humors without any other stimulus. The same must be said for the nature of plants and minerals.

Hence, how insane are those who day and night pursue health, yet do not know the source from which all health and life proceeds. Let them, then, cease barking against the Philosopher’s Stone, unless they are wicked and cruel, wishing to abuse the light of their own life by ignorance.

Thus, it must be concluded: Whoever, by divine fortune, has been granted the Philosopher’s Stone and knows how to use it, will not only enjoy sound health throughout the course of life under the joyful title of well-being, but may even prolong his lifespan beyond its usual term—so long as Divine Providence does not object—and through a happy and long life, will be given to inquire into the centuries of others, in praise of his eternal Benefactor. This is not beyond the limits of nature, but sanctioned by the law of nature: that whenever a body, overwhelmed by contrary faculties or diseases, is inclined toward death by unbreakable law, the vital spirit will abandon it and return to its homeland as nature fades.

No one who has even faintly perceived the scent of Philosophy will deny that the life of animals—or the vital spirit—being spiritual and of the nature of the aether (from which all forms descend through celestial influences—here I do not speak of the rational soul, the true form of man), has no affinity with the earthly body unless retained by some medium partaking of both natures. If this medium were not most constant and pure, life would always flee and receive no permanence from it, since it is certain that no one can give what he does not have.

In the substance of mixed things, the radical moisture of things is the most constant and pure, since it is the subject of all mixed nature, as we will later teach in its own chapter. Therefore, it will be the medium and capable subject in whose center the life of the body must consist. For the center of radical moisture is the innate heat, the true fire of nature, and the true sulfur of the wise, which they have learned to reduce from potency to act of the True Philosopher in their Stone.

Therefore, whoever possesses the Philosopher’s Stone possesses the radical moisture of things, in which, through the most sagacious and natural art, the innate heat exercises its chief powers. Indeed, the whole heat, having determined its moisture and transmuted it into what is called fiery sulfur by decoction, is contained in it.

The entire nature of the mixed body lies hidden in this radical moisture. Hence, whoever has the radical moisture of any thing has already obtained the entire essence, powers, and faculties of that thing—provided it has been extracted with sagacious industry and by a natural medium and physical art, not by that vulgar Spagyric-Chymic art which has polluted the world with its extracts and acrid substances and has taught little or nothing good. But first it must be understood what this radical moisture is, of which, in the chapters below, everyone will be sufficiently instructed if he reads, and does not spare effort in repeated study.

Let them, therefore, consider how great a weight lies in the hands of him who has obtained the Philosopher’s Stone. For if someone, through the nourishing substance of exquisite food or the powerful essence of a balsamic remedy, recovers lost health—though both food and remedy are taken wrapped in coarse skins and mixed with waste—what must be said if their radical moisture, or more precisely, their core and center of virtue, is administered in a suitable vehicle?

All the more, since this marvelous medicine does not stir nature by incitement, stimulation, or violent movement, but gently and naturally restores the natural heat, of which it abounds, and rejuvenates the languishing nature of the body. It performs marvelous—indeed incredible—operations in animal bodies, for then not the physician's hand, but blessed nature itself serves as both doctor and medicine.

All common medicines, as we said above, are merely irritants to nature, by which the living being is urged to exercise its faculty and regain its dormant powers.

Hence, after taking some medicine, the sick often languish more, appearing at times joyless and weak, almost lifeless. The reason is that all the medicines used in this age are purgatives, which, by their intrinsic qualities (even if administered sweetly), irritate nature, which then tries with all its might to expel the illness.

Therefore, it is nature alone that expels waste and it is her faculty alone that has power in such cases. Thus, stimuli are useless when nature is languishing and weakened, and does not respond to the medicine's provocation. Indeed, the condition worsens, and the body, now impotent, is forced to surrender, and the image of death is stamped upon it.

An example is the clyster or medicine introduced into the intestine separated from the body, in which it does nothing, nor does it possess any purgative power, because there is no nature there to be stimulated by the clyster like a goad to purge itself. Hence, if nature alone is effective in a healthy person to expel excrements and other harmful humors, why do we irrationally provoke this languishing nature and increase even greater excrements with the same stimulus, when it would be more appropriate to strengthen it and impart new vigor through our medicine? What marvelous cures and miraculous effects in health would arise from this method of administration? Truly incredible.

I do not deny that there is sometimes a medicine which strengthens the heart (cardiac) or contains other properties besides purgatives, but this is used rarely and only in certain cases. Worse still, such medicine is prepared in a crude manner and is weak in virtue, appearing almost useless and ineffective; in its administration the sick person often nearly gives up their vital spirit and becomes unfit not only to receive the virtue of the medicine but not even to feel it.

I do not deny that there are other medicines found that free nature from contraries not by irritation but by their specific quality—such as rhubarb and similar substances called "specifics." And in truth, if such medicines were appropriate to be administered in all diseases, healing would be certain and undoubted.

But who knows how to find such things, and how to prepare and administer them properly? Uncertain knowledge produces uncertain effects.

Therefore, Philosophical Medicine is suitable for all diseases—not because it contains different qualities to produce various effects, but because it has only one faculty, which is to strengthen nature and give it the highest powers.

Hence those err who deny that all diseases can be driven away from the body by the Philosopher’s Stone, since in the body there is only one nature, which must be strengthened by this one medicine, so that it may be able to free itself even from infinite diseases, if they were present.

This is perhaps that medicine of which it is written in the Holy Scripture: “The Most High created medicine from the earth, and the wise man will not reject it.” It is, I say, from the earth, because the Philosophers knew how to extract it from the earth and elevate it to the heaven of its virtue. It is the medicine of which, once one knows it, one no longer needs a physician—unless one uses it in madness, in excessive quantities, beyond what is proper and fitting to nature.

It is, indeed, the purest fire of nature, which, if it is too great, devours a small flame. Just as an animal is choked by too much food, and the natural faculty is overwhelmed by excessive substance, so the strength of the body is consumed by the abundance and overflow of this [medicine]. Just as one loses strength from excessive joy, so the fire would be dispersed by excessive heat. Likewise, fruits, roots, and all vegetables—even though they live and are nourished by water—are destroyed by excessive floods. Hence in all things, as in these, prudence, not imprudence, must prevail.

It is not surprising, then, if this Stone performs such great and marvelous cures when administered by the hands of the Philosopher. For even the most stubborn, virulent, and incurable diseases are immediately healed and driven away as if by a miracle of nature, because nature in the sick body is so invigorated and strengthened that it fears no illness and is burdened by no malign quality—it overcomes all contraries.

Nature, O wretches, is what imparts health to you—if only you knew how to restore it. If you have oil for your lamp, do not fear its swift extinguishing (unless God wills it); do not dread the tyranny of diseases, so long as nature holds a safe citadel and a reserve of aid. Why sweat day and night with such exhausting cares, if your efforts for health are unfruitful? Why waste your time and mind on so many sciences, useless services, elegant lectures, and readings, with only popular example and empty opinion to show for it?

Let it be your care to understand the Philosopher’s Stone, the foundation of your health, the treasure of riches, the knowledge of true natural wisdom, and at the same time a sure understanding of nature.

But now it is time to speak a bit about the truth of this art: whether it is possible and true, especially with regard to the tincture which the Philosophers promise—to transmute imperfect metals into gold. For if someone knows its possibility, they will no longer doubt the doctrine and may have the will to follow it.

But setting aside the authorities of the authors and Philosophers—which can be seen in books specially printed for this—we will rely only on the same reasoning which was sufficient for us, and which we urge the reader to follow more than the doctrines of others. Thus, we have delayed by such discourse before touching upon the truth of the matter.

All metals are nothing but coagulated mercury, either in part or wholly fixed. Here it would be lengthy to bring forth all the affirmative authorities supporting this opinion. But, as I said, even in this matter, leaving them aside, we are certain from the effect that the material of metals is mercury, because all things that occur during their liquefaction, and the properties by which the nature of things is known, point to mercury: they have weight, mobility, brightness, smell, easy liquefaction, and they do not yield to superimposed weight, for all things float upon them; they are liquid and do not wet the hand or other things; they are soft, and—what is more remarkable—when liquefied, they vanish into smoke like mercury, in a shorter or longer time according to the degree of heat or fixation, except for gold, which due to its complete purity and fixation does not evaporate but remains stable in flux with ignition.

Metals not only show these properties of mercury when liquefied, but also others—for instance, the easier mingling with mercury than with any other sublunary body, for nothing mixes with another except that which is of the same nature. And this is the principal property of mercury. Hence, due to their common mercurial material, which metals possess, they also mix with each other.

Thus iron, because it has little mercury (in which metallic virtue consists) and much earthy sulfur, is also difficult to mix with mercury and with other metals. It only acquires a mercurial luster and the rest of the above-described properties by art, which are more or less found in the other metals.

Furthermore, ductility—which consists in mercurial union and the gluing together of the radical moisture in which mercury abounds—is a property common to all metals. The more they abound in mercury, and the more fixed it is, the more ductile they are. Therefore, gold is more ductile than other metals.

Not only by these manifest properties is it known that metal is nothing other than mercury, but also by the anatomy or dissection of the very metal this is confirmed. For from all metals pure mercury of the same essence as common mercury is extracted, and the whole substance of the metal is reduced to it, according to how much it participated in it. Hence we extracted less mercury from iron than from other metals. From this, it is to be considered more imperfect, just as gold is more perfect because it is wholly fixed mercury.

We may therefore conclude that just as gold is the true perfection of metals, and wholly metal because it is wholly fixed mercury, so only that metallic substance in metals should be called metallic which is the substance of mercury—whether pure or impure, cooked or uncooked. This difference, however, does not change the species, for even fruit, whether more or less ripe, sour or sweet, is still the same in species, though differing in degree of ripeness. Just as an unripe grape (omphacium) differs in quality from a ripe grape, yet both are the same in species. Nor is a healthy man distinguished in species from a sick man, or an infant from an old man.

Given all this—that metals consist solely of mercury as their metallic substance—their transmutation will not be impossible, but rather their maturation into gold, when this can be accomplished by mere cooking, which is induced by the physical Stone, the true metallic fire, which in a moment performs what nature does in a thousand years, in the hands of the Philosopher.

This Stone is made from the middle and purest substance of mercury alone. Hence, if common mercury enters and mixes with metals during their fusion as water mixes with water, what shall we say of that noble, most subtle, and penetrating medicine derived from it, brought to the highest purity and exaltation? It will certainly permeate all mercury, even in its smallest parts, and, as of its own nature, embrace it. And because it is fiery and redder than all redness, it will dye it and adorn it with a citrine color. For redness in its highest degree, when mixed with much whiteness—as is in mercury—produces a citrine color, because its redness is tempered by that whiteness.

As for fixation, we say further that the substance of mercury found in all metals (except gold) is crude and swollen with excessive moisture. Hence the dry naturally attracts its own moisture, tempers it by drawing, and by drawing dries it, and by dryness balances the moisture. When this balance is achieved, the metal is now equalized and perfected gold.

Thus, because it is neither too moist nor too dry but partakes of both, in this balance the volatile part no longer dominates the fixed part, but is retained by it in fire. And because by nature’s work the earthy and the humid are homogeneously united, in the substance of mercury either the whole evaporates or the whole remains. Thus fixation and constancy in fire are given, with no evaporation of moist parts, which does not happen in other bodies because of the lack of such balanced mixture.

Hence it is seen that this moisture, by its supreme dryness, purity, and penetrability, enters the substance of mercury included in metals and dyes and fixes it, with the excrements separated—not present in the test. For only that substance can be converted into gold, all others being excluded.

Now the error is revealed of those who think that an imperfect body like copper or iron, or another, can be wholly converted into gold by some medicine without separation of its excrements or dross. For it is impossible unless the mercurial moist substance alone be brought to the end of gold. And those who presume such things are impostors. Such transformation is not granted except into something of similar nature.

Thus, those who say that nails or other instruments immersed in a menstruum are transmuted into gold speak falsely, for they do not understand the nature of metals. Even if part of the metal appears to have been transmuted into gold, and another part remains in the original metallic form, do not believe that the metallic part was transmuted. Rather, it is either a trick or a portion of natural gold cleverly glued to the impure metallic part, so that the whole nail or instrument seems golden to the eye, but the deception is detected by a discerning intellect.

These were the things that revealed to me the possibility of this science, which I believe are sufficient for anyone intelligent, if they compare all with the possibilities of nature. Let them consult other authors, and before undertaking the work, read what follows in this treatise, and re-read it with repeated study.

THE END

LUX OBNUBILATA

By its own nature shining forth. True

THEORETICAL ON THE PHILOSOPHICAL STONE.

Canzone 1. First

Out of Nothing came forth

The dark Chaos, a shapeless mass

At the first sound of the omnipotent Word:

It seemed that disorder had given birth,

Or rather, that the Creator

Had been a God. So much were they inactive (me),

In Him all things,

And without dividing spirit, confused,

Every Element was enclosed in Him;

CHAPTER ONE.

The work of Creation, as Divine, thus requires a supernatural intelligence for its understanding; About those things which it is not fitting to speak above us, nor should we incur Daedalian danger: neither parabolic nor hyperbolic spectacles can reveal the inclination of that invisible infinite point to us. Nevertheless, since it is fitting to know the Creator through those things which are created: and the ineffable nature of that order requires, through things produced outside itself, to declare its own essence though confused; nor will it be inappropriate to follow the poetic teachings of our Author, and to amplify his learned discourse on that ineffable work by a greater explanation, so that it may serve the utility and benefit of all, and the advantage of the novices of the Hermetic art: and let it, for the glory of such a great architect, manifest as much as possible his workmanship, according to that prophetic saying: The heavens declare the glory of God, and the firmament shows the work of his hands.

Without a foundation laid beneath, it is impossible to build above: nor can the mass of a building be constructed without a base; what is denied to the creature is not incongruent with the Creator; nor is it a marvel, since He Himself, the foundation (or, to speak better, the principle) of His works, lacks no more solid foundation for the structure of His hands. If I ask, why the immovable earth, struck all around by air, remains? why the mass of heavens and celestial bodies moves so orderly around? nor is the fundamental basis of these visible to the eyes? The answer is sufficiently given by saying they are carried above the center, and the center is their foundation base.

A great Mystery, revealed not to all. The foundation of the whole world is the uncreated Word of God; for if it is proper to the center to manifest the image of a point, in which neither duality nor division occurs: what is more indivisible? what greater Unity than the Word of God?

The point of the center is no less indivisible than invisible, only comprehensible through the circumference: the Word of God is invisible except through creatures comprehensible. From the center point all lines are drawn and in the center terminated: from the Word of God all things created came forth, and to it they shall return, completed through this circular revolution. The immovable point of the center, while the sphere turns: the immutable Word of God, while all perish. Just as from the center all things flowed out through dimension; so all will recede to the center through constriction, that one by uncreated goodness, this by hidden wisdom.

The ineffable Word of God, so to speak, is the center of the world; from it this visible circumference flowed out, retaining somewhat the nature of its first principle. For all things created by God keep the holy dogmas of the Creator and imitate His supernatural workmanship as much as possible. For the earth offers itself as the point of the center of visible things. Every fruit and any created thing contains and preserves the point to the eye, from which they flowed out in the center, from which all forces as lines from the center, or rays from the luminous body, came forth. The microcosm, which symbolizes the adequate image of the whole world, does it not also contain the heart as the center, from which all arteries, lines of vital spirits, and most shining rays proceed in the middle?

What was its exemplar? Nothing but the structure of the whole orb: What order so great? Nothing but the highest Creator’s document, so that just as all His presences are needed, so they are governed by His order. It is therefore firm: from this point are derived these infinite lines.

But at that beginning of creation what form or shape would it have? This question has been doubtful and uncertain for many until now; But if we rightly consider the nature of things and examine the disposition of the lower things, we will opine without any insane doubtful error that an aqueous vapor, or humid mist flowed forth from the beginning. For among all created substances only humidity is more properly defined by an alien term, and is the adequate subject for receiving all forms, it alone had to show itself also the subject of the subsequent order in creation; For as our learned Author keenly touched, that dark chaos, or confused mass, which ought to be the most suitable and capacious of all forms (as the first matter, according to Aristotle, and all the most learned Scholastics born to be formed by forms, indifferent to all) ought to have the essence of vaporous humidity.

From the later production of lower things we learned that any seed of that undigested mass and deformed mass must be clothed in aqueous moisture: for the seeds of plants, containing a hermaphrodite nature, thrown into the earth to be revived, do they not first rot and pass into mucous humidity? Generation of the sought thing in any kingdom, as we will show below in its chapter, does not occur unless first to that first matter, or chaos, no longer universal but specific, things, that is seeds of things, are reduced.

Therefore, the seeds of plants, so that they may be preserved for a long time outside their body in which they were enclosed, incorrupt and unfading, nature has decreed that they be contained in a hard shell, which defends them from the injury of the elements and other harmful things: But when we wish to have a new generation and multiplication from them, it is necessary to revive them and reduce them again somewhat to the original chaos; But the seeds of animals, being more noble and swelling with a more lively spirit, could not be contained outside their body unless they had a shell harder than even marble, which would disgrace the nobility of that compound and the convenience of generation: Hence the very wise nature did not separate that seed from the body, but kept it as if raw and truly aqueous in the body itself; which seed is driven by the excitation of lustful motion (as will be better explained below) into a matrix appropriate for it, as into earth there to be wholly revived by the union of the more humid, that is the seed of spermatic nature, and afterwards to multiply itself not only in the quantity of virtue but also in mass by nourishment.

Which we demonstrated in the two kingdoms above, purely animal and vegetable: and why we do not determine it in the mineral? Because we will teach that in its particular chapter, we leave it for its place.

There is no doubt that aqueous humidity, or vaporous mist, was more suitable for that chaotic embryo or formless mass, from which the foundation and basis of all generations should arise. This is fully proved by Evangelical doctrine, where it is said of the Word of God, that all things were made by Him, and without Him nothing was made that was made; For it is said, He was in God, that is, in the beginning was the center, or infinite point, which is the first principle, the incomprehensible eternal Word, from which point all things were made, and without this point nothing could exist; What that water was from which the first chaos arose from that point, Moses teaches in sacred magic, and demonstrates with a secret yet learned indicator: since it says that immediately light was created, and the spirit of the Lord moved upon the waters, and no measure of any other substance was there except the form of light and water as the subject before the coming out of the divine spirit, chaotic and formless.

Although at the beginning it said: God created heaven and earth: and it made mention of the earth: it is not therefore to be understood that the earth obtained distinction from heaven before light had obtained distinction from darkness; Because it was unsuitable and opposed the most noble order for the separation of light to be posterior, and consequently the lowest parts to be produced before the upper parts; And if the chief opinion of the theologians is that at the time of the creation of light, the cohort of the noblest angels and spirit of noblest nature was created: how unbecoming it would be that the grossest element and the dark dregs of the whole world should have been produced before the production of that most noble intelligence: Beyond that I ask: whether heaven and earth at that time were distinct in the order in which they are now, or confusedly mixed? If distinct, then the earth is the center of the world and heaven above it surrounding it spherically, how could the motions of heaven, without light, from which all motion is derived, exist? If you say it was not moved then: then the earth by rest and deprivation of light would have been again absorbed, and migrated into the original chaos without any distinction: For light was to flee darkness and to drive it to the lower waters, as we say. If however, they were not as now placed; then they were confused and not distinct into heaven and earth: nor could heaven have obtained its name, that is the firmament of division, but the same (as we said above) chaos, an unregulated and shapeless mass: which we concede; Moses therefore placed the general distinction of the whole world there into heaven and earth: and took heaven for the more visible part of the upper part, and earth for the lower elemental part, because the earth is more conspicuous, thicker, and elemental. Later he explains a special distinction of the parts of the world, and declares that the nature of light was produced from that eternal point, which being the most fitting form of that vaporous humidity, was seen to be the origin of all forms instantly: Therefore, that most cloudy appearance of water was first obtained by that primitive chaos; which is better understood while he goes on to say that he separated the waters above the firmament from those below the firmament: Hence it clearly appears that above and below there was nothing but watery substance, created in a marvelous way as the adequate subject of all forms.

Throwing this foundation, we must proceed further to demonstrate this divine workmanship. They flowed out, as we said, as confused and disordered vapors from the center, which were called abyss, upon whose face darkness proceeded. Now, as our poet teaches, all elements gave confused and disordered work to rest: so that all things under the deep silence seemed as in the sleep of death: no action of agents, no alteration of passives, no mixture of changers, nor the vicissitude of new generation or corruption was present: indeed, they seemed inactive and fertile.

Canzone 2

Who now could tell again

How Heaven, Earth, and Sea were formed,

So light in themselves, and vast in mass?

Who can reveal how

Light and motion came to be above in the Moon and Sun,

The state and form below as we see?

Who can ever understand how

Every thing received its name,

Spirit, quantity, law, and measure,

From this disordered, impure mass?

CHAPTER TWO

LUX — from that eternal and immense treasure of light — as a shot arrow, at a fixed time flowed forth, and with its radiant light banished darkness, drove away chaotic terror, and introduced universal form, just as before, the universal matter had been Chaos. Hence immediately it was seen that the spirit of the Lord was spread over those watery substances by its own inherent motion, as though impatient to produce, to fulfill the will of the eternal Word.

Here, through the production of light, the noble firmament was created, as a medium between the first parts—that is, the more subtle parts of watery gloom—and the lowest, thicker parts of water. From that intense and fiery light afterwards, impregnated by the Spirit of God, the highest angelic creatures were created by the Supreme Architect of things; if not from nothing, then by the natural faculty of the spirit wandering above the waters of the firmament in the higher Empyrean, it held a free office in carrying out the commands of God.

The command of the eternal Name indeed is diffused in inferior creatures. The ways of that Order are the teachings of nature and all the inferior things; for every creature is a likeness of its Creator and shows this noble order: just as from the center of the eternal Maker continuously flowed rays of light wandering to the circumference, so any created body, by its imitation, constantly pours forth its rays, though invisible and endlessly multiplied; such are the visual rays, or rather spirits of light, which although enclosed and compressed in opaque bodies, nevertheless perform their office in radiating.

This mystery is not known to all, nor revealed to all; for all bodies are known by the reflection of mirrors, from themselves continuously sending out rays, which, reflected in the mirror glass, enter the eyes of the beholders, where vision is formed (whose natural inquiry we will provide separately in the second part). It suffices now to know that those rays, or as they are called, spirits emitted from any body, are nothing but parts of that original most pure light; though obscured.

Only light strikes through glass and the hardest diamond, which is denied even to the most subtle air. This is the command of the divine Word, that in every point every creature show the order of the supreme point of creation as much as possible; which we will better demonstrate in a special book for the eye, God granting, to His glory and the consolation of the son of the art.

Now by that spirit of the Word of God, the subtler and purest vapors are gathered, which, participating in that immense light, were to be adequate objects of light. The firmament itself was then seen to be adorned with the beauty of luminous bodies; sparks of light shone; trembling stars sent their rays to the sky; when the Creator, rejoicing in all beauty, gathered greater light in the single Sun, to give there especially the eternal seat to His beneficent Majesty, according to the prophecy: "In the Sun He placed His tabernacle."

Because of this unceasing and radiant light, then the day broke forth; then the elements were moved; then the principle of generations was near, only awaiting the eternal Word’s command: yet the lower waters, although sympathetic, had not yet become equal to the higher: so only by the swiftest movement did that purest substance of ethereal agents act in the lower; hence the wise Architect joined the middle with the lower, so they might follow one another with a sweeter and gentler motion.

From this the Sun was created; then the Moon, the noblest womb of Masculine light, in the same order; so that receiving from the Sun the fruitful and fiery light, mixed with a more humid light, it might impart its ray better suited to the lower natures: thus, the Sun was called the Prefect of the Day, and the Moon the Mistress of Night; whose position was placed in the lower part of the firmament not for another reason but that it might better receive the influences of the higher and transmit them below.

Thus from the less pure part of the higher waters, composed and gathered into one substance, light too must have been more obtuse, colder, and more humid; and changes under the moon must not be said to come from another source, since the moon’s light and body are more akin in nature to the inferior: the middle uses light more than the extremes themselves. But now it is time to pursue the Order of Creation.

Now in the lower waters, by the firmament and the lights of the bodies, great alteration and confusion of elements arose; when from the purer part by the action and rarefaction of the higher, our air, which we breathe in the belly of the waters, seemed to rise again; yet the thickness of the waters surrounded it, disturbed. Hence, as said by the Word of God, the waters were gathered into one Sea, and the earth, as the excrement and dregs of that first chaotic mass, appeared dry.

But what is to be said of the motion, vastness of Heaven, and the stability of Earth, and the continents therein, as our poet hints? Certainly it seems difficult at first for us who are the lowest to know the highest; it is better to leave this task to the dwellers of that heavenly region and to clarify these higher matters. Yet it would be a sacrilege against divine grace for us, who are partakers of that purest light, to abuse it. For the celestial soul, although it has an elemental body, is truly an inhabitant and citizen of that glorious homeland, if it does not disgrace itself, and may speak marvels of that province according to the extent of its intellect.

It is impious to believe in a work contrary to God’s harmony, to believe impossible things in knowledge, those things which belong to the same order, though of a purer condition; since there is only one Author, in whom there is no variation, whose order does not allow exception, nor can it attain higher nobility, because it is equal to wisdom and goodness.

For the most benign Creator willed that those incomprehensible things created outside Himself should be knowable, so that by them we might come to the knowledge of Him. The same creature is Heaven, the ether, and the most noble body of the Sun, as is any stone or even the dust of despised sand; hence the lesser is no less knowable, and that is intelligible. Perhaps you believe, O Zoilus, that the human body, lesser in nobility and order of manufacture, is greater than Heaven itself; rather, Heaven and the World are ordered by Divine goodness with much greater order and structure.

Therefore, with a tearful spirit, even about those things that we shall inquire above us by knowledge of the lower, light adds light, and a small spark kindles a greater fire.

But before we investigate the distinction of the heavens, first it must be seen what is meant by Heaven. Certainly what the Sacred Scripture teaches us who worship the true God must be the norm, and true Physics in the order of creation must be taught in the sacred pages. For Moses, moved by the Lord, wrote what he had been inspired to say: a truly perfect Magus, and also instructed in all the wisdom of natural magic (as all who wrote about him assert).

Hence whatever can be said about the order and knowledge of Creation in sacred Genesis is taught holy and truly, though in a secret style. It is therefore held certain that there God said He made a firmament in the midst of the waters to divide the waters from the waters; and God called the firmament Heaven. Therefore by the name Heaven nothing else is understood except what is also called the firmament.

It is likewise established that there were two kinds of divided waters: one kind above and another below the firmament, which is the same as saying waters above Heaven and waters below Heaven. It is taught that the waters below Heaven were gathered into one place so that dry land appeared; the eternal Creator called this gathering of the lower waters Seas. Therefore all that is above these lower waters deserves to be called Heaven, that is, the firmament, by one name.

It must not be said that these waters can transgress the divine command, ordering the lower waters to be gathered in one place, which would be most disobedient to the Divine Master of nature. Since we see the waters above the clouds are not elevated, it must be asserted that the firmament, that is, Heaven, is contained immediately above the clouds.

Water naturally rarefies by the action of agents; therefore the higher it ascends, the more it should rarefy according to natural reason, and the greater the rarity, the greater the capacity of the place; yet even considering the immense capacity of the place helping, waters are rather compressed than rarefied; and they are constrained as though the hardest glass or the most solid crystal were blocking them.

This must be philosophized about by the cold and other more remote causes; it is enough to say the command of God and the waters execute that command when He ordered them to be gathered and separated from the higher by the firmament.

Therefore it may be repeated, Heaven indeed and truly speaking is contained from the beginning of the clouds up to the highest waters, called by many the crystalline Heaven. Thus there is one Heaven, no less one firmament, as taught in the Sacred Page, which is the divider of waters.

But that this Heaven ought to be divided into several parts will be done for the sake of a more attractive explanation.

For God placed stars in Heaven and other luminaries, and there, according to the nature of the luminary, they had their proper place according to their natural law; the firmament is nothing but the division of waters, or the confusion of that chaos through which light was to wander to illuminate and shape the World.

Yet light is more spiritual and invisible to the bodily eyes, so it needed some opaque body so that through it it might become sensible to other creatures; hence the Supreme Creator made luminous bodies, as we said, from the gathering of the upper waters into such a body, and imparted light to it according to His will, so that it shone everywhere for the lower.

Just as to each body fashioned by God in this lower region the lower waters have supplied the matter, so what was produced above must be said to be made only of the matter of the higher waters.

Why multiply matters, when it was convenient to induce all subsequent separations from one confused Chaos?

Therefore, the conglomerates of the superior waters, some parts into a spherical form, according to the nature of that water itself, which always conglomerates spherically, the light has adorned and placed them with infirmity (which is clearly taught in that sacred Genesis) so that some may be present for the day, others indeed for the night, and so they may be signs of times and vicissitudes of the sublunar elements. Whence from this it is clear how vain and impious is the effort of astrologers, who judge those bodies for foreseeing the hidden judgments of God about future contingencies concerning morals, the actions of men, and other accidents, which alone can be foreknown by the mind of the supreme Creator, in whose word all things are included, and from whose will all things proceed and are observed. But let us leave them to fluctuate in their error; it will suffice for us to prognosticate from those bodies the alterations of times, elements, and vicissitudes of the whole year, which will be infallible to the intelligent and experienced.

The luminous bodies in that vast firmament have each obtained a fixed position and place, and there are balanced by their own nature; for they are light bodies by the nature of the superior waters, as we said, nevertheless in regard to the firmament, and because of the immensity of their mass, they would be heavy and would transgress their place if, by the command of God, and by the governance of the Intelligence assigned to them (as some theologians have rightly opined), which presides over any creatures' bodies, having received the rapid motion of the first Mover, they were not governed in their position and posture; for the circular motion is of such a nature that whatever is moved by it remains in its own sphere and in the ecliptic, so to speak. Experience shows that any weight, whether lead or marble of whatever magnitude, when rotated spherically, loses its weight and as if flying is carried around the center of rotation. For any very thin thread could restrain the gravity of that weight equally from the center by a tether; likewise any wheel, however immense and large after the first impulse of motion, moves by its own nature, and the greater it is the faster and easier it rotates around its axis; whence it is not surprising that the bodies of the luminaries, even if extended and of almost infinite magnitude, are lightly carried around in their own sphere, fixed at no varying point, as if attached to the most solid wall. Such motion is caused by nothing else than that most lively spirit of light, by which those bodies are animated; for the spirit is restless and impatient, and from it the powers and actions of the vital spirits depend, as we shall sometime say in a particular book about the marvelous structure of man.

Therefore, the heaven is properly taken for the firmament, which by its nature is unique and undivided; but because we, who are placed in a lower place, see whatever is above us as adorned with the mantle of heaven, thus we also call the position of the waters and the empyrean by the name heaven: for sometimes the denomination may be taken from the more visible and evident; the lower elements are called earth, just as the higher are called heaven, as Moses has generally spoken; whence whatever is above us is heaven, and whatever is beneath this is earth. Then it will be easy to divide this upper part called heaven into three orders, as if into three heavens distinguished.

First, therefore, if it may be divided, heaven will be that region immediately above the clouds, where the thicker waters recognize their appointed boundary from the Creator under the firmament, up to the position of the fixed stars: that is to say, the place where the erratic planets, so called because they do not observe order in their motion among themselves, but move distinctly by wandering, to give form to the universe and execute the changes of times. The second heaven will be the site of the fixed bodies, in which the stars proceed in order, always observing the distance of waters between them; whence by such unchanging motion they are called fixed, as if they were affixed to some more solid body; nevertheless, the first and second heaven are successively united, and no distinction appears, while the firmament is the same and the same upper part of the universe, as we said. The third heaven will be itself the place of the superior waters divided by the mediating firmament from below, where the cataracts of the heavens are preserved to execute the hidden judgment of God, which sometimes seemed to be the floods of waters to repress the perdition of men, in the time of the flood of sins, an examiner and not executor of divine justice: up to this third heaven, which is near to the empyrean, where the divine Majesty and supreme monarchy and the order of spirits reside, it is to be believed that St. Paul was rapt; for no further boundaries are assigned in the sacred page.

If these waters are moistening, it cannot be denied, yet with undoubted knowledge it must be said they are not moistening; for they are waters rarefied by the purest rarefaction and are spirits of waters: for if it may be allowed to take an argument from the stronger, let us say that if the rarefaction of the inferior waters, which are thicker and as it were the dregs in comparison to the superior, prohibits in this region of the air that they should moisten, although they are extended everywhere and spread through the whole air, much less will those superior ones moisten; diffused in a most vast place and by their own nature more subtle. Hence, the more water is rarefied, the more it approaches its pristine purity of nature, which being placed above the firmament, is the most noble part of the etheric. From such rarefaction of the waters and their nature the Philochemist Hermetic should receive greater instruction than from all the science of Aristotle and his sect, however sharp and learned in a different kind. This seems to be hinted by Sandius in his new light, where he teaches to observe the miracles of nature, and especially he says in the rarefaction of water etc., which we will explain better in its place.

What the matter of the firmament was like, whether there was a vacuum there or something distinct from the surrounding waters, seems doubtful and uncertain; but if we rightly consider the natures of things, although the secrets of the superior are distant and obscure to us, still it will be granted to explore them. The substance of the waters, as we said, supplied the universal matter of the whole world, like light supplies the general form; but because in the firmament above all, the light, spread everywhere, had to be restrained, and there more abundantly to flourish, its dwelling place had to be more akin to the nature of light than to the material substance itself, so that in its own and free place light could wander and appear more splendid; for it is known that air or the nature of air is closer to light or fire than water is: for we have the example that our fire lives by air because of its nature's kinship. Hence it will be manifest that in that ethereal region the purer elements thrive: namely light for fire, firmament for air, and superior waters for water; but earth, since it is not properly an element, but the bark and dregs of the elements, therefore since in that place there is no room for excrement, the seat of earth is rightly denied; for since the fiery light is there in its own home, it naturally did not need to be preserved violently or with a hard crust as in our regions; as will shortly be said below.

About heaven and its bodies, it has now been said; now let us come closer to the lower elements, and because mention has been more often made of the inferior waters and their congregation, let us bring something forth.

Separated by the Word of God from the inferior waters into one place, and this aided by the action of light and the retreat of darkness, which sought to flee to the lowest parts, behold a new chaos of inferior nature somewhat represents itself: for there were the other elements disordered and confused, and no action arose; when the wise Creator conceived to grant light to this nature; but since it was of the nature of light to rise on high, and there was no fitting subject there, He gave them a dwelling place, as much as possible suitable to Him, which is fire and the charioteer of light, otherwise without this most noble body, light could not be held; but because fire is the purest and driest part of this second chaos, that is the purest air; it naturally attracts its own natural humid, and by natural action it would consume and extend itself into a greater quantity, so as to burn nearly the whole world, and consume all the lower air and water converted into it; whence provident nature, or rather the Author of nature, if He wished to grant fire to us as the vehicle of light, had to assign it a very hard prison, namely earth, and hold it in most impure coverings, lest it escape freely, but bound by a double bond, namely by the coldness of the earth and the thickness of the water by antiparistasis repelled by its contraries, it was detained and enclosed for the benefit of the lower nature. Now you have fire as form, that is the vehicle of light, and its seat in earth, that is in the bark or dregs of the lower water placed and detained.

This fire acts on the matter nearest and most apt to suffer, namely water, which immediately rarefies and is converted into the nature of air, which is the air below the clouds, mixed with water by the attraction of the superior. If such fire in the center of the earth finds the aerial humidity produced by its action enclosed, no previous exhalation on account of the hardness and opacity of the earth, then it again acts upon that humidity, and joining itself with the drier and subtler parts of the earth, with this added aerial humidity, there results bituminous sulphur of the earth differing according to the place. But if that air reaches the place of exit, it moves other air and causes winds; but if that fire acts on aqueous humidity, exhaled air, and uniting itself with the purer and driest parts of the earth, to which it adheres, it is common salt: whence from here depends the cause of the salinity of the sea. For the sea’s basin is as the deepest, and as if it reached the center of the earth, where above all the central fire thrives, on account of the vastness of its basin and the quantity of waters gathered there and the certain quietness they cause, that fire acts continually on that humid marine matter, the aerial exhalation always rising by some moment through the pores of the water, whereby salt is generated; the causes of the said exhalation are the storms, the sea’s whirlpools and tides, which come from the sea. But about these, their flux and tide, we will say at a better time in a better explanation; it is enough to know the general cause, arising from the exhalation of that aerial humidity, which is not retained as in the most closed places of the earth, where sometimes that aerial exhalation is moved and afterward suddenly finds another closed place, and so immense motions of the earth arise according to the quantity of matter. From that continual action of fire in the depths of the sea, in the aqueous humidity by union of the subtlest parts of the earth, as we said, salt is made, which by the fluctuation of the sea is drawn from the caverns of the earth, and the water itself is impregnated by the continual motion and becomes salty. But passing these salty waters through the pores of the earth excluded in linen, that fire is not able to act, where the basins of that fountain or river are more shallow; for the generation of salt does not begin on the surface of the bottom, but under the earth; hence if the basin is closed, covered so that it has smaller pores or the water does not enter deep enough to serve the generation of salts or the produced salt is not drawn off and so the water is not impregnated, then it remains dispersed in the entrails of the earth; the water on the surface remains, as it was, fresh. In the depth of the sea, where the quantity of sand is found, the exit of the water is given so that it may enter and be imbued with the substance of salt and thus become salty.

Behold heaven, earth, and sea produced from that shapeless chaos, whose natural dimension established this world; whose law, order, and measure, because it is my intention to clarify in a particular book, are therefore left to the reader.

3.

O you, sons of the divine Hermes,

Emoli, children to whom the paternal Art

Makes Nature appear without any veil,

You alone, only you know

How Earth and Heaven were formed,

From indistinct Chaos by the eternal right hand:

Your great Work

Clearly shows to us

That God in the very manner by which

The Physical Elixir is produced, composed all things;

CHAPTER THREE

Only the sons of the whole Hermetic discipline know the foundation of all nature: only they truly see Nature, to whom the light of that Nature is evident. They are like northern births, to whom at the origin of their nativity it is granted to look upon the Sun, the source of light, with fixed eyes; indeed, they handle the Son of the Sun in their hands, draw him from the well, wash him, bathe him, nourish him, and promote him to a more mature age. These are the ones who truly worship Diana the sister, who had a second fortune in their nativity horoscope under favorable Jupiter; who, as if the Creator’s monkey in the making of their stone, venerate the supreme Creator, worship the Merciful One, imitate the wise as much as possible, pray humbly, praise eagerly, and those possessing the gifts return thanks...

For who would believe from one confused little corpuscle, where nothing but filth appears to vulgar eyes, where only abomination is found, that the wise Chemist could extract his obscure and mercurial humidity, containing all things necessary for the work? Near to this Mercury is whatever the wise seek, who may extract from it hidden elements of the waters above and below, to be drawn out by a second physical separation, purified, and promoted to the act of generation after corruption? Who would ever believe that there is found the firmament, the divider of the superior and inferior waters, and the bearer of luminous bodies, in which the luminous bodies themselves sometimes suffer eclipse? Who would ever believe that fire is enclosed in the center of the earth? That fire which is the charioteer of light, a fire which does not consume and devour, but nourishes and is natural, and is the source of this nature, by action in the depths of the Philosophical Sea, and that salt is generated, and in the virgin bays of the earth the true sulfur of Nature, the Mercury of the Wise, and the Philosopher’s Stone are found?

O happy you, who joined the superior waters with the inferior ones in the middle of the firmament! O wiser you, who through fire and water saw the earth, burned it, and sublimated it in the ether! Surely the glory of earthly beatitude adheres to you, and all obscurity will always flee from you. You saw the superior waters not wetting, you handled light with your hands, you constrained the air; you nourished fire, sublimated earth into Mercury, into salt, and finally into sulfur. You recognized the Center, extracted rays from the center of light, expelled darkness through light, saw a new day. Mercury was born to you, you held the Moon in your hands... The Sun was born, reborn, and exalted for you; you worshiped the Sun in its redness, greeted the Moon in its whiteness, and adored the other stars in the darkness of night. Darkness before light, darkness after light, and light appeared to you together with darkness... What more shall I say? You produced Chaos, extracted form from it, had the primary matter, informed it with a nobler form, corrupted it with a second form, and transmuted it into form. No more should be said, for it is not fitting to speak more in this science than is proper...

4.

But I am not fit to portray

With a weak pen so vast a comparison—

I am not yet an experienced son of the Art.

Yet if I certainly hit the mark,

Your writings reveal themselves to my eyes:

Though well-known to me is the wise Illiastus,

Nor is the marvelous Composition hidden from me,

By which you have extracted by power

The purity of the Elements in act.

CHAPTER FOUR