On certain matters in Chemistry that have been passed over, on the occasion of which secrets of no small moment and things hitherto regarded as non-entities are frankly uncovered and demonstrated.

Buy me CoffeeJOELIS LANGELOTTI, Doctor,

and Chief Physician to the Most Serene Duke of Holstein, the Regent.

LETTER

to the Most Excellent Curious of Nature.

On certain matters in Chemistry that have been passed over, on the occasion of which secrets of no small moment—and things hitherto regarded as non-entities—are frankly uncovered and demonstrated.

HAMBURG,

at Gothofredus Schultze.

Also available at AMSTERDAM,

at Joannes Janssonius à Waesberge.

A.M. 1672.

Translated from the book:

Epistola ad Praecellentissimos Naturae Curiosos. De quibusdam in Chymia praetermissis, quorum occasione Secreta haud exigui momenti ... deteguntur & demonstrantur written by Joel Langelott

Most Excellent Gentlemen, Lords, and Most Honored Patrons,

Very recently—though, to my regret, all too late—I found myself deeply, indeed ardently, stirred by your invitations, you who burn with so great a desire to advance the public good, so that I thought nothing should be considered before this: by what means I too might publicly attest that I approve in every way of this your undertaking, and that I am also willing to lend you whatever help I can, if only the slightness of my powers permits. And it occurred to me that certain points from my chemical observations might be useful, which I have not hesitated to set before the eyes of your Curious, inasmuch as they have seemed to me not quite everyday matters, not the worn-out commonplaces of the chemists, but such things as may rouse more skillful minds to attempt greater matters and to work out those secrets of the Art which hitherto have come into the knowledge of only a very few.

It has always seemed astonishing to me how it came to pass that the chief chemical operations—what people commonly call “processes”—have up to now counted for nothing, but rather have lain neglected as distasteful and were held for false, some even being classed among “non-entities.” At length I discovered the true cause of this: namely, that the cultivators of the art have not applied, in the manner and at the time required, those means which most of all ought to have been employed.

Of these operations, however, I have found by sure experience that three especially stand out and afford truly wonderful uses: namely, Digestion, Fermentation, and Tritum—to use Pliny’s familiar word—indeed names worn smooth even to beginners; yet as to their use, they have so far become known to few even among veterans. This I must now show by some clear experiments, so that I may hearten those who labor at Chemistry not to give up so quickly precisely where they ought most to press on, nor to cast away at once the hope of this or that process even if it seems doubtful. I would also advise the critics not to ply too hastily a censor’s pen upon things untried and but little understood.

And thus, first of all, I will show the notable use of Digestion in preparing volatile Salt of Tartar. How highly this has hitherto been prized, and with what painstaking care it has been sought by the curious, it is not my purpose now to recount at length. The difficulties that befell me I shall briefly embrace in a word. For after many processes toward this very volatilization had been attempted in vain, at length I came.

I never thought I should reach my goal better or more quickly in this matter than by joining the fixed salt of tartar to its volatile counterpart; yet even so I did not make good enough progress—only a very little of the volatile salt rose, while the larger portion remained at the bottom of the vessel. But as soon as I took proper account of time and called in long digestion to my aid, the operation succeeded so well that at the very first attempt I obtained what I had feared I should scarcely achieve after many repeated trials: namely, volatile salt of tartar, of a most snow-white color, with only a few tasteless dregs left behind, quite earthy in hue.

Another use of Digestion in preparing the Essences of Mineral Sulphurs.

A like benefit from Digestion I have experienced in many other matters, especially in duly preparing the essences of mineral sulphurs; however, I shall for the moment bring forward here only one experiment concerning coral, since together with many other cases, it seemed to me worth placing most plainly before everyone’s eyes that great power and efficacy of Digestion. Some years before I had poured over fragments of red coral a quantity of oil—among vegetable distillates, so far as I know, the mildest—intending to try whether I could extract a tincture with it. But I was disappointed: after a sufficiently long time I observed that neither the oil nor the corals changed in the least. Therefore, casting aside the hope of good success, I gave no further attention to that little cucurbit.

But last winter, while I was occupied with other labors in the digestion furnace, it pleased me to take up again the coral experiment so long laid aside and to set that same cucurbit there once more—and not without happy success. For scarcely had a month elapsed, when, as I shook it in the usual way, I noticed the fragments of the coral, becoming a little more intensely red and softening, though without any change in the oil. I therefore continued with the same degree of heat, and after a few days I saw—greatly to my astonishment—that the corals had been completely resolved into a very ruddy mucilage; while the oil still floated above it in its former state and had not taken up even the least tincture.

I shook the little cucurbit hard and often, to see whether I could unite the oil with the coralline mucilage; but I accomplished nothing—the oil always rising and the mucilage settling. I tried whether I could unite them by digestion, but that too did not succeed. I was therefore compelled to separate things that refused all union; and, the oil having been drawn off (which I found to retain almost its original smell and taste), I poured upon the remaining mucilage tartarized spirit of wine, by which, after a brief digestion, it was, it allowed itself to be dissolved into a very deep-red tincture.

By this twofold experiment I think I have made plain how great is the force of long digestion, hitherto neglected. Let philosophers/chemists also consider here how great the action and energeia of volatile salts may be, if fetters be put upon them so that they cannot so quickly fly away.

I now come to Fermentation—how much usefulness it affords in chemistry I could now confirm by several experiments. I have indeed observed a marvelous fermentation in antimony, pearls, corals, and many other things (which, if God so wills, shall one day be fully described in the Acts of the Gottorp Laboratory).

For the present it will suffice to pursue our tartar, and to explain somewhat more exactly its true dissolution and volatilization by the way of fermentation, since it is so greatly desired by all physico-chemists and by the more exact physicians. That this very volatilization can be achieved most easily by the method just mentioned the following operation will show.

First calcine two or three ounces of crude tartar, only lightly, and to some slight blackening—so that you may have the ferment most needed for fermenting tartar.

Into a very capacious pot pour so much water (after it has been put in place) that it stands about a finger’s breadth deep; apply at first a gentle heat so that it only grows warm; then strew in half a handful of tartar finely powdered. In a short time you will see certain bubbles arise and increase more and more. When you see this, continue as you began, sprinkling in the powdered tartar by divided portions; and thus a greater fermentation is stirred up aroused, and the bubbles then rise in such neat order that you would think you were looking at natural grapes themselves—save for the color. This sight I have more than once contemplated with great pleasure; and from it I have drawn a sure argument that crude tartar is not lacking in that which we are compelled to grant to other salts prepared by art—namely, that they can exactly present the form of their original abode.

But here a careful government of the fire is needed—a moderate one, such as every fermentation requires. Take care also that by too liberal a sprinkling an excessive boiling up is not excited, and that the fermenting matter, as often happens, does not run over the rim of the pot.

When the fermentation has ceased, transfer everything in the pot into an iron cucurbit (for with a glass one there is danger it may crack), since you must rather often apply to it cloths moistened with cold water, in order that the excessive ebullition of the fermented tartar may be checked; for otherwise, being impatient of excessive heat, it is wont to be carried swiftly upward and even to enter the receiver itself. For this reason also the fire must be governed with the greatest caution and increased by slow degrees—yet at the end strong enough that all the salt may be driven over.

You will likewise find that, if you proceed rightly and properly, that gross and feculent tartar is by the aforesaid fermentation rendered so subtle and volatile that not even the least particle of fixed salt remains in the caput mortuum—a thing I have proved not once only.

The liquor that comes over, since by reason of the much water added for the sake of fermentation it is heavily charged, must also be rectified at length, and indeed so far until it shows a somewhat whitish hue, which is the sign that there is in it the due quantity of volatile salt. How highly this is to be esteemed, the testimony of Helmont alone might have sufficed; yet, to oblige the chymiatrists, I willingly add that I have found its use not only in the internal affections of the body, but also in external ones—indeed, even in gangrene itself—in a marvelous degree; and that by its aid I have prepared certain Essences which we had in vain attempted with other menstruums. Thus we have found that faithful warning of Helmont to agree most exactly with the truth.

(marginal: cf. Helmont, On Fevers, ch. 15, p.m. 780.)

But in very deed there still remains to be set forth another use of Fermentation, and a most notable one: namely, that by its benefit crude, impure sulphurs—so hostile to Nature—can be separated most excellently and most conveniently. This the following preparation of opium will show, which I cannot but commend as of the best kind; for it yields a medicine quite safe and free from the common reproaches, nay truly a panacea, bringing a thousand benefits, if one knows how to use it skillfully.

(marginal: Another use of fermentation: in separating noxious, impure sulphur.)

(Marginal: The true Essence of Opium)

Take one ounce (℥ j) of Thebaic opium, cut into small pieces, and pour over it, in a low cucurbit, ten pounds of the very freshest juice of well-ripened quinces; add one ounce of pure and very dry salt of tartar. Then set it to a gentle heat for a day or two, until some little bubbles appear—this is the sign of impending fermentation. Next, in order to promote it, add four ounces of sugar most finely powdered, and thereafter keep that degree of heat which fermentation requires. Thus the work will go on quite well, and you will see the opium plainly rise and be resolved into very small parts. But beware of the narcotic sulphur of heavy odor which is then wont to exhale. You will then also observe that part of the impure volatile, foamy portion seeks the top, while the more earthy part settles at the bottom of the cucurbit, to settle; and in the middle there will remain the purer part—a reddish liquor, clear like a ruby.

This you will carefully separate, filter, and by due distillation thicken to the consistency of honey. Dissolve this again in alcoholized spirit of wine, filter it, and digest for a month, so that whatever crudity still remains may by that celestial fire be matured and perfected. When the spirit has been drawn off to a proper consistency, you will find this Essence to be of such power and efficacy that a quarter of a grain, or at most half a grain, mixed with its appropriate vehicle—whether you wish it moist or dry—suffices for the intended purpose and yields truly marvelous effects.

Now I turn to Tritum—indeed quite familiar in the pharmacopoeias, though not so among chemists—to whom it will perhaps seem a paradox that I extol it with such praises, and say that for this alone it is to be wondered at…

(marginal note:) TRITUS — its marvelous use in chemistry, and first in preparing the true potable gold.

…able to be achieved in chemistry. And I am confident that anyone will readily agree with me who will but fix his eyes and mind upon the two operations that follow (passing over many others for the present). Experiments of both were carried out in our Gottorp laboratory, in the presence of the Most Serene Prince FREDERICK, of most glorious memory—a prince accomplished in every branch of knowledge, and most especially in chemistry.

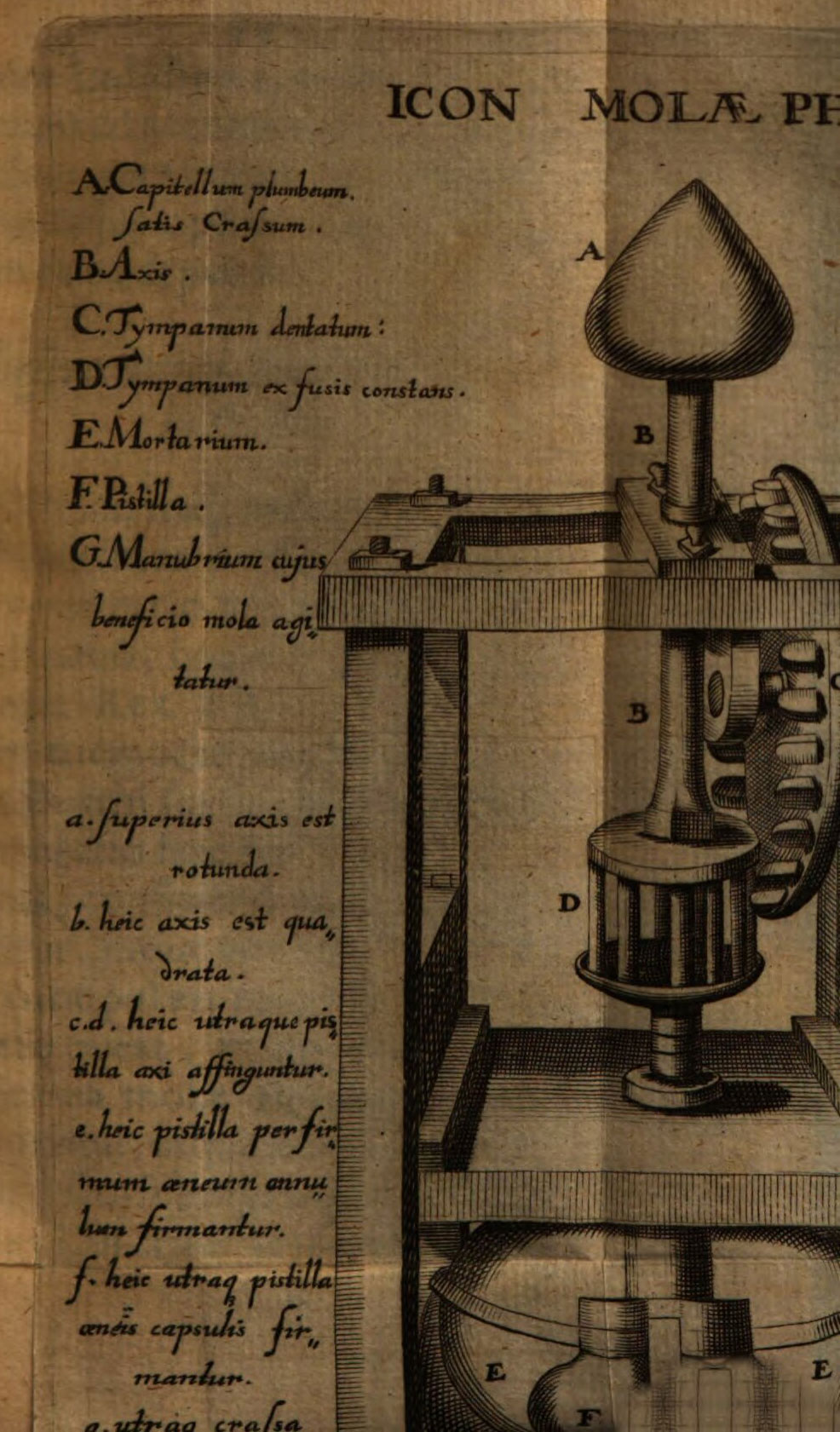

It was indeed a marvel—and this first befell us—that GOLD, that most fixed body (to speak in the chemists’ manner), submitted to the power of TRITUS; whereas otherwise it yields neither to extreme fire, the tyrant of the world, nor to any other of the strongest menstruums. Yet it yielded to this, as we saw with our own eyes—though only when a unique instrument was applied; and on account of this astonishing use we have given it the name “the philosophical mill.”

(marginal note:) That some sort of TRITUM of gold was in use in Pliny’s time is evident from Natural History Book 36, ch. 26, and likewise Book 33, ch. 4.

…we have given it this name, and we have taken care to describe its structure here the more exactly, since the whole success of this operation depends upon it.

The outline of the instrument to be inserted here.

Accordingly, gold, beaten into leaf as required and cut into the smallest particles, is placed in a very dense glass mortar (or a golden one), of the kind which the most august King FREDERICK of Denmark, of blessed memory, shortly before his death had caused to be made at the urging of Borrhius, as soon as this operation was first introduced in these parts. Into it the gold is put, and, the mortar being covered only with paper so that no dust or other thing may fall in, it is ground night and day with the mill kept in continuous motion, until it is converted into a brownish-black powder; for which grinding fourteen days is for the most part required, fourteen days must be spent at it; but if one wishes to work only by day, a whole month will be required.

Then put this powder into a small retort not too deep but flat—such as the English ones are wont to be—and drive it in a sand-bath fire, first by degrees and at last with the strongest heat. In this way there will distil a few drops indeed, but most ruby-red, which, either by themselves or digested with tartarized spirit of wine, yield true potable gold, not counterfeit nor tainted with any foreign quality.

The residue, although we could also readily reduce it by further grinding, we preferred to extract with our philosophical vinegar (prepared by long digestion from verdigris, sulphur, and alcohol of wine); and so again we obtained a tincture quite ruddy and of altogether great powers. The very small portion that still remained, by the aid of borax we reduced by the help of borax back into a body, but it lacked its due weight.

At first sight, indeed, this operation seems rough—demanding much time and toil and little art. Yet, in the upshot, it is truly marvelous, aided by that marvelous Salt, the sole catholic solvent of the Air. And that this salt is drawn out by continuous grinding many other experiments made on this subject have taught me—matters which I reserve for publication one day in the Acts of the Gottorp Laboratory.

A second experiment of TRITUS will display the true and genuine preparation of the Mercury of Antimony—that Mercury which a recent author of “Non-Entities” has assailed with so many shafts and has therefore consigned among the chemical non-entities. But this censure must be forgiven a physician and anatomist otherwise very experienced and most deserving because in chemical matters a man does not always reach the goal he has set for himself.

And pray, what kind of conclusion is this: “this or that process does not succeed—therefore none succeeds”? To play the critic is a matter of great moment, and belongs only to those long and much exercised in the art. No man’s authority will frighten me from making public and communicating this process—not for empty vainglory, but moved solely by love of truth—a process which I myself once worked out in the presence of my most gracious Prince FREDERICK, of blessed memory; and I further took care that the same should be performed by the hand of the most practiced chemist of the Saxon Electorate, Johann Kunckel, so that I might not rely on myself alone, nor lack such a testimony as may put those rash censors of “Non-Entities” to shame.

And to that end it seemed good to send to you, Most Excellent Sirs, Kunckel’s own letters as the surest witnesses of this operation, so that I might win the greater credit for poor Mercury, and leave nothing undone that may serve to vindicate his honor.

Now the chief part of this work consists in TRITUS. Therefore, first grind the regulus of antimony to an impalpable powder. To one pound of this add two pounds of the purest and driest salt of tartar, and eight ounces of sal ammoniac; mix thoroughly, then moisten with the urine of a healthy man—and, if it can be had, of one who drinks wine. Take care that this mixture be ground upon porphyry by two very strong, brawny youths for a whole day without the least intermission, always sprinkling on urine whenever the moisture fails; afterwards the mixture, put that mixture into a cucurbit, and pour over it so much urine as to stand two fingers’ breadth above it. Keep the vessel duly closed, cherish it with a gentle digestion for a full month, and shake it daily. If in the meantime the mass appears to grow drier, add urine again. When the digestion is finished, mix in equal parts of powdered glass and quick-lime, form the whole into small pellets (globuli), and dry them in the shade.

From these you will draw out Mercury in the following way. First have ready an iron vessel, oblong and shaped like a cucurbit, into which cold water must be poured, and bury it in the earth. Upon this set an iron plate pierced with many holes, and place upon it the well-dried pellets; then fit to it an iron head likewise, somewhat hollowed/lowered, so that you may conveniently lay glowing coals upon it; and thus maintain a moderate heat for four hours keep this heat as prescribed, then increase it for the same number of hours—up to the utmost. Afterwards, before it has cooled, beware not to move the vessel buried in the earth, nor to pour off the water until it has quite cooled; otherwise you will lose much Mercury, as happened to us the first time, when the Most Serene (impatient of delay) ordered it to be poured off too soon, and so would have caused a loss. For Mercury, having been broken down by so great a force of fire into the smallest atoms, must by cold be coagulated again.

And thus I think I have duly fulfilled my promise concerning the Mercury of Antimony. Let the critics raise whatever they please—unconquered truth will stand. For the Mercury which I myself prepared with these hands and handled, and even saw with these eyes running in the bottom of the vessel after the distillation was finished—no one will persuade me to believe that it is a Non-Entity.

Nor will I be moved in the least if, for the very unskilled operators, this or that of the preceding processes should not, at the very first attempt, turn out as they wish. It is enough for me that I have brought forward nothing here which I have not myself tried by my own experience and carried through to the end, and—which many perhaps will marvel at—have described thus far quite openly and candidly.

Let those who are newcomers in the Art and unlucky workmen consider how many things must be observed beforehand, and in the operation itself, and also after it, if one would be certain of the result. This will be clear even from the single operation on tartar. For by no means is all tartar of the same quality; indeed I have been able to note hitherto a great diversity in it.

Next, the fermentation of the tartar itself must be carefully managed: for if it be less than proper, then that too, even in the least will not be dissolved; nor will the “grapes” present themselves in the natural form in which they ought; nor will all the salt—which is the chief point of the work—be volatilized. And if perchance during the distillation the fire has been excessive, much of the volatile salt will also be burned, and it will render the spirit heavy-smelling, like the common sort.

I add no more, lest I seem to linger over trifles. And I think by this single example I have made clear with what circumspection one must act and judge in chemical matters.

What remains, Most Excellent Gentlemen, is to pray that the supreme Deity may deign to bless further this your glorious enterprise, and to grant to each of you the years of Nestor, together with the aids by which—once stirred—you may reach the proposed goal at full speed and happily promote the glory of our common fatherland, Germany. Farewell, and continue steadfastly to show me your favor.

I turn to you again, Most Excellent Gentlemen—trusting in your kindness—that you will the more readily accept even this slight supplement, since it seems to serve to illuminate the foregoing.

After I had already added the colophon to those matters, there happened to come to hand among my papers another operation concerning the Tritum of gold, once communicated to me by a friend well skilled in chemical affairs, and highly commended—chiefly for this reason, that even without the ministry of fire it would distil a ruddy liquor. At that time, however, I could not bring myself to give it credence, but rather left it undecided.

Now, while I am reviewing operations of this sort, I have begun to examine this one also a little more carefully, and at length have judged it worthy that the curious I lay it before your curious eyes, since it seems to me not to promise a vain result. And that you may judge of it the better, I have thought it best to preface a rough sketch of the instrument.

a. Mortar.

b. A steel body which is to take the place of the pestle.

c. The space between the two steel bodies, in which the gold lies.

d. The handle.

The mortar (a) is made of the purest steel. The body to be inserted into it, which is to take the place of the pestle or grinder, (b) is likewise of steel, and it ought to correspond to the mortar in the very shape in which it is drawn—save that at its base it should be three fingers’ breadth wider, and thus also thicker.

The space (c) is that in which a gold leaf—of a thickness equal to half a ducat—is laid.

The handle (d) is what by which that steel body (b) must be kept in motion, as my friend advised, for three weeks; and so at length the gold will be resolved into a potable liquor.

You see, Most Excellent Gentlemen, what this newly proposed method of working is like—plain, indeed very simple, and involving no artifice. Whether it will approve itself to you, I am eager to know. For my own part—speaking frankly what I think—it seems entirely so, nor have I any doubt that it seems to me that gold can be resolved far more quickly and readily in this way than if it were put into a golden or glass mortar such as we have used—because of the sulphureous-saline quality of Mars (iron), which, being freed from its fetters by this grinding and raised to the highest degree of subtlety, acts the more powerfully upon the very compact substance of gold; and at the same time it attracts the aerial salt in greater quantity than can ever be done in a golden or glass mortar.

I foresee, however, what the more shrewd will object to me—namely, that by such continued grinding steel particles are abraded and mixed with the gold. I do not wish to contend against those who think so; but I would ask them also to weigh this: how near is the kinship of these sulphurs, and how great is the benefit of digestion, which at length separates the pure from the impure and excites that hidden martial fire, well known to the genuine adepts of Nature—a fire which, aided by the alcohol of wine, is able very well to cook down that little which is still unripe to its due maturity.

Have I said much in a few words, and satisfied the doubt raised above? You, Most Excellent Gentlemen, are well acquainted with Nature’s operations. On this occasion I again and again urge all who aspire to the secrets of the art to let Nature be their guide and mistress, and to hold commended to themselves the two chief means by which she produces and perfects things—namely, Fermentation and Digestion. The very ample use of each I have briefly indicated in the foregoing letter, and I could confirm it with several more experiments; but let this suffice for the present. It should be enough for the physico-chemists that I have shown by two experiments the great use of Fermentation, especially in preparing the true Essence of Opium, which others have sought in vain by another route; for they will certainly never attain the true aim of chemistry, which is the separation of the pure from the impure. Let them also consider how very far the common method of preparing opium differs from this, and how exceedingly small are the fruits to be gathered from that method—whereas by this [method] they are most excellent and altogether marvelous.

Digestion is of yet greater use, and under it is included Maturation, hitherto unknown in the chemists’ workshops. Let the physico-chemists only weigh the experiment I have reported about corals: for who would readily believe that a body so hard and stony could by digestion alone be converted into a soft, somewhat pliant mucilage? Who would believe that the tiny tincture contained in corals could by digestion alone be so increased that their whole substance appears as nothing but tincture? Therefore it is enough…

Thus by these few experiments I think I have indicated what the physico-chemists ought to follow in imitation. Farewell, Most Excellent Gentlemen, and be pleased to regard this slight supplement with fairness and goodwill.

FINIS.