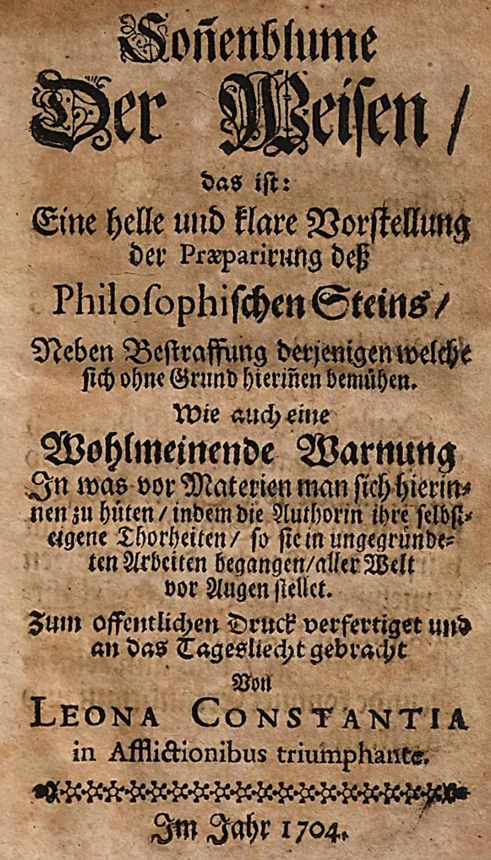

Sunflower of the Wise - A bright and clear presentation of the preparation of the Philosophical Stone

Listen Audio Book Buy me CoffeeSunflower of the Wise

that is:

A bright and clear presentation of the preparation of the Philosophical Stone; together with the chastisement of those who busy themselves herein without cause. Likewise a well-intentioned warning as to what materials one must beware of in this matter; in that the authoress sets before the eyes of the whole world her own follies committed in unfounded labors.

Prepared for public print and brought to the light of day by Leona Constantia, triumphant in afflictions.

In the year 1704.

Job 28, v. 12.

“But where shall wisdom be found, and where is the place of understanding? Behold, the fear of the LORD—that is wisdom; and to shun evil—that is understanding.”

Proverbs 2.

“Then, if you call after it earnestly and pray for it; if you seek it as silver and search for it like treasures; then you will perceive the fear of the LORD and find the knowledge of God. For the LORD gives wisdom, and from His mouth come knowledge and understanding.”

Translated from the book:

Sonnenblume der Weisen: das ist: Eine helle und klare Vorstellung der Praeparirung dess philosophischen Steins

To the most gracious and beloved Reader.

It is indeed all too true that only those ought to write books who can do so and have learned it; the others, being unknowing, should only read and hearken to them, so that by means thereof they too might obtain understanding. The former may then, not without reason, be set before me as a lesson.

That I, however, venture to bring this little tract openly to the light of day has this single and only cause: that for a long time I dragged myself about in Chymie and had to endure the greatest toil and labor therein, so that now, out of heartfelt compassion, I would gladly, sufferings of others, who likewise are by no means less involved therein and perhaps have not yet come so far that long-continued ignorance finally becomes for them the best guide—namely, to take the way back in good time—may, by means of my own harm, receive a proffered light, so that, if they should not proceed further and reach the shore of felicity with the richest enjoyment (which few attain to, a very few excepted), they may at once make a firm resolve to turn back again, and thus be spared exceedingly great toil and danger in the future.

Hasten then, beloved reader, to grasp what my purpose is—one for which I can in no wise be blamed—unless it be the case that upon this my little thicket there settle not only the useful bees, which from all flowers, even the bitterest, suck an excellent medicinal honey, but also perchance harmful ones spiders or other poisonous creatures—for it can scarcely be otherwise—should settle themselves there; at which one need by no means marvel. For already in Solomon’s time harmful flies spoiled the most artful ointments.

What, then, are we to expect now, in these still greater times of corruption, wherein more than in the first world all flesh has corrupted its way? Surely nothing else than contempt, abuse, and mockery—indeed even judicial judgments—on the part of one’s fellow man.

But should a soul that longs for wisdom trouble itself that it must be judged by those who are themselves full of vices? Should one who has only now endeavored, as far as lay within his weak, wretched, sinful powers, to love God and his neighbor as himself—should he care, when people revile him and pursue him to the uttermost?—and ah! were they even men! For to be a man is that which God created upright; but now, through the world’s “artificing,” whereof Solomon speaks (Eccles. 7), it has been altogether corrupted.

No—by no means; for it is a small thing for a Christian to let himself be judged by men. The good opinion and back-biting of people takes nothing from our piety. What matters it whether the world accounts thee this or that? Only see to it that thou mayest stand before God’s judgment.

Therefore, when thine enemies revile thee and speak evil of thee, and the winds of persecutions blow about thee, and thou art come upon the wide sea beneath the waves of evil tongues—then withdraw from the storm-winds into the chamber of thine heart and quiet the same. If it be there still and at peace, thou hast cause to rejoice heartily; for when thou you have in your heart—and among pious, Christ-loving people—a good name, you can desire nothing more; your virtue will make you sufficiently renowned: rejoice only in your innocence.

For a man lives today; tomorrow perhaps he is no longer here—why then do you fear men? Therefore you must not seek your peace in the mouths of men, but solely in God and in your good conscience.

An upright man diligently seeks how he may daily improve himself, and in such points he finds so much to do that he does not even think of his neighbor’s doing or leaving off—unless it be a matter that it serve the good, perhaps to offer that same neighbor a helping hand in one or another mischance; which indeed is every Christian’s bounden duty, so much so that whenever we but see someone who is in need of our help, it should be enough for us to know our neighbor’s needy poverty; for when we anticipate our friend’s desire, then we double our beneficence—as the excellent Jesuit Bona, in his Manuductio ad Coelum, treats of this at great length. But in these times of great corruption this is by no means the aim; rather, one is busied in prying narrowly into one’s neighbor’s doings and leavings-off, so that on the benches of the mockers there may be matter enough to make everything out for the worst and to draw it through the comb.

Since we know that this is the custom only of those who seek to amuse themselves with the world and worldly things, those who seek true wisdom must nevertheless regard such people always with an eye of pity and compassion, in the hope that at length the time will yet come when they will arrive at the knowledge of themselves come to it.

Meanwhile, by no means seek to take revenge, but keep these evil desires bridled by reason; perform the works of virtue not with burden, but with delight and joy; cast all unjust affronts to the winds, and with a cheerful spirit strive to accomplish our work—keeping the same with us in secret and not making a show of it.

When, then, you are satisfied with the witness of your good conscience and find yourself continually occupied in this virtue without ceasing, you will at length also bear away virtue’s reward. For to exercise oneself in virtue is the most excellent work of a Christian—whereby you, who otherwise are still revenge-minded, can best avenge yourself upon your haters and persecutors. Guevara speaks of this very thoughtfully in his epistle: he says, in all the world there is no more heartfelt triumph than when one by means of virtue, bears and forgives the disgrace done to him.

The burgomaster Mamilus once asked Julius Caesar what was the most noble honor in the world. He was answered: “Mamilus! I swear to you by the immortal gods that I know nothing in the world wherein I gain more honor, nor anything that delights me more, than when I forgive those who revile me.”

Phalaris the tyrant swore by the immortal gods that he had never become angry over an evil word. “For,” said he, “if a pious man has spoken it, I know that he has spoken it for my good; but if a fool has spoken it, then I take it as a pastime.”

Thus one sees that we must still learn patience even from tyrants. Emperor Aurelius used to say that Julius Caesar obtained the empire by the sword; Augustus inherited it; Caligula came to it through his father, who had subdued the Germans; Nero brought it about by tyranny; Titus received it because he had taken Judea; Trajan attained it through his bravery and noble mind; but Marcus Aurelius obtained it by no other means than by patience—for it is a far greater virtue to endure the insults of the wicked than to dispute with the jurists in the high schools.

That, furthermore, one may see how by means of virtue one can best avenge oneself upon one’s enemies, is shown by the words of the excellent orator Cicero. He once said to the Romans: “I know that you are not envious of me because I am not the person that you are, but because you cannot be the person that I am.” And in such a case I would rather that my enemies be envious of me than that my friends should have compassion for bear with me.

If the heathen have spoken thus, and knew how to exercise themselves in this excellent virtue—why then should we, who call ourselves Christians, not only refuse to imitate those praiseworthy heathen, but all the more step into the footsteps of our mirror of virtue? His express command is: “Bless those who curse you, that you may be children of your merciful Father in heaven.”

But so that, as this point has led me somewhat far afield, the preface does not become greater than the treatise itself, I will only add this: namely, to give a brief answer to those who perhaps will presume to rebuke me, as a woman, for undertaking matters which, they say, do not at all befit that sex—since it is, after all, commonly known what work they are supposed to claim for themselves, namely to attend diligently to the kitchen and the distaff to wait for; and since this is more than too true, I will not trouble myself long to prove this truth with counter-arguments (though the same might easily be done in many ways), but will only add the wise sayings of that Roman woman Cornelia, of whom histories report that her writings were so excellently and keenly composed that even Cicero could have made use of a woman’s writings; who among other things also spoke these words, namely: If the name of a woman did not put Cornelia to shame, she would rightly be the foremost among all the sophists; for from such tender flesh I have never seen so lofty and deep sentences flow. From this it is plain to see what that excellent heathen, Cicero, thought of the writings of a woman.

This Cornelia speaks, in her very wise instruction to her two sons, among other things these words: I render unspeakable thanks to the immortal gods for the grace shown me; first, that they made me intelligent and not foolish, for it is enough that women by nature are otherwise weak, without their having also to be accused of folly. Secondly, that in my trials they gave me strength to overcome them; for only those troubles are truly to be counted as troubles which cannot be borne with any patience, and only that person is unfortunate to whom the gods deny patience in his necessities.

This, then, is briefly all that I am minded to answer on this point. And since I conceal my name, no one can therefore fall into the thought that I do this out of pride, to let myself be seen. Be that as it may, I am content, for I know that by this I desire to serve my neighbor. Whoever believes it and receives it with the same heart with which I communicate it in all sincerity will be able to draw manifold benefit from it; but the others I willingly let go their way, and I advance bravely and undaunted to my intended work.

The eternal Wisdom of God has so greatly exerted itself that it lets itself be heard even on the open way and in the streets—indeed at the gates by which one enters the city—with a strong voice and cry, and breaks forth into these words: “O you foolish ones! how long will you be foolish? and how long will you scoffers delight in scoffing, and you godless hate instruction? Behold, I will pour out my spirit unto you and make my words known to you.”

From this loving summons of eternal Wisdom, which the most-wise King Solomon sets forth in his instructive Proverbs, it is sufficiently to be noted that the ignorance in which, generally, the blind people of the world are stuck does by no means arise from the fact that the most high God, who distributes His gifts so abundantly—especially to those who ask and call upon Him—should refuse them anything, or leave them stuck in their ignorance and blindness? No, by no means; rather God, who is Wisdom itself, gives us knowledge and understanding; He enlightens our eyes so that we can see; to our mouth He gives the distinction of taste; to the tongue, speech; He provides the sense of smell, of touch, of walking.

In sum, our whole body is a representation of the great world; therefore man, with the greatest right, is called the little world. And what is more: within it dwells and rules the immortal soul, which has its origin from the breath of God, and which, after the frailty and perishability of the body (for man is earth, and shall again become earth, from which he was taken), shall again return to God; for God has compassion on all His works and creatures. Thus this immortal soul—after the putrefaction of the body, which shall then gloriously rise again and be made clear—shall once more be united with the body, to the praise and glory of the eternal, infinite God.

Therefore the fault must of necessity lie in human beings themselves because of their ignorance; for it is said that they hate instruction and will not have the fear of the LORD; they would not heed the counsel of the LORD, but even blasphemed all His reproofs. Then God says: they shall also eat of the fruit of their own way, and be filled with their own counsel.

One sees therefore plainly that this willful disobedience of the foolish brings them themselves into misfortune; and hence it is no wonder at all when people in general remain stuck in their blindness and ignorance and do not keep to the right way, must miss the right way. But with those who seek Wisdom with a longing soul, it is quite otherwise: they fear the Lord with all their heart—which is the true beginning of wisdom; they seek Him with an earnest spirit and call upon Him, since He is near and to be found.

All worldly honor and riches they cast at their feet and reckon them as loss; they use them only as incidental means. Instead they seek solely and alone the heavenly wisdom, strive after it before all else, firmly assured that the rest (so far as it is needful) will be added to them. Their mind is always directed toward God; they use outward things in such a way that their heart clings to them least of all, nor can they be turned aside from their appointed goal.

They love God with all their heart, and this law of love does not at all permit that, alongside God, one should love anything else and turn oneself to creatures—for that would be the greatest corruption. In sum: since they seek nothing other than God and divine things, the Lord God does not deny them their request, but gives them much more than they desire. He grants them understanding both of earthly and of heavenly matters; all of nature lies disclosed before them; in it they behold the greatest marvels; from these creatures they learn to recognize their Creator ever more and more. They perceive Him in His glorious works which He has made from the beginning; they recognize God in His mercy, and they in turn practice mercy toward others; they recognize Him in His righteousness and judgment, wherefore they will not stain themselves with any injustice, nor in any way deal unfairly with their neighbor.

Justice is their garment is righteousness, and truth their chief adornment. And should it happen—as commonly does not fail to occur—that they are insulted by their haters and persecutors in one way or another, and that from their enemies they suffer the utmost, both the robbing of honor and goods and other shameful abuses and oppressions (for it is the very nature and condition of Christianity to be despised, mocked, reviled, and slandered—yet a true Christian rejoices in this disgrace, and therefore he binds all these lies and slanders about him as an ornament; for if the world did not so deal with him, he would lack the mark of being a holy child of God), nevertheless they follow the admonition of the Apostle: “Avenge not yourselves, my beloved, but give place to wrath; for the Lord is the avenger”—that is to say, the Lord who repays all things will also repay your enemies; He will surely requite their wickedness.

He will hurl the sling-stone upon the jaws of all your foes—and this the godly souls know full well; therefore they bear all things with patience. They know that the Lord, the Lord, will set all this right in His time, and that the Lord holds a cup in His hand, which is filled to the brim with strong drink, of which the godless must drain the dregs.

They know that the Lord will arise and have mercy upon Zion; indeed, He will bring it to an end, so that they need no longer hear the voice of the oppressor. They also know that when they have finished their pilgrimage here, then they shall have a building of God, a house not made with hands, but eternal in the heavens, where they shall behold God face to face—for they shall see Him as He is, and shall be transformed into the selfsame image. O my soul! Marvel here at this divine vision, and bow thyself before so holy a God. O my soul! Let nothing in this world—though the temptation be ever so great—keep thee from this wondrous contemplation. O press through to that eternal brightness, to behold this everlasting light for ever.

O when shall the time come that from this fragmentary state I shall be brought to highest perfection and to the eternal light, and thus, with unspeakable praise, behold Him who is all in all in His everlasting clarity—so that I may raise that ineffable hymn: Holy, holy, holy is the Lord Sabaoth. Here I must fall silent; for what tongue, understanding, sense, or reason is able to express this?

And so let us indeed lay ourselves down with utmost humility before the throne of grace before the throne of the Most High, clothed with sackcloth about our loins and with cords about our necks, lamenting plaintively our great unworthiness, beseeching most humbly that God would clothe us with the garments of salvation and with the robes of righteousness, washing away our many great sins in the Blood of the Lamb; and just as God in this temporality and earthliness has opened our eyes that we may here behold the wonders of His mysteries, so also may the most high God deign to tinge and clarify us unto eternal glory.

Now, to come at present to my purpose, I say that the matter upon which our Stone is prepared is a mean and unseemly thing. It is the stone that is despised by most; in it there is not to be found the least beauty; it sometimes lies at every man’s feet, and is not even accounted worthy even to be picked up. It is recognized by no one except by the eye of the wise; he is the true Samaritan who brings it into the artist’s inn, where its wounds are washed with oil and wine. And when it has now come again to its health, it is thereafter able to free its brethren also from their infirmities and to bring them with it into the most excellent state.

But to this glory they can come in no other way than by being lifted up through the Cross; for the first beginning of our Stone is the Cross, its midpoint is the Cross, its preparations all take place in and through the Cross; upon its highest step of honor it sits upon the Cross and bears in triumph a sceptre of the Cross in its hand—which is also called its twofold serpent-staff. With this staff it works wonders: it can divide the sea into two parts so that one may pass through with perfectly dry feet; he can strike water with this staff from the hardest rock. In sum, with it he can bring upon the Egyptians all the plagues—so that this staff and stone are of a wondrous origin.

Yes, it is precisely the matter out of which God in the beginning created heaven and earth—namely, out of a lump. Take this lump and deal with it just as God in the beginning dealt in the creation of heaven and earth.

This earth was waste and void (that is, utterly without form, so that no one knew what it should be), and darkness was upon the deep (there was a vast abyss in the place where now heaven and earth stand, and this same abyss was full of thick darkness, as if a black fog); and the Spirit of God (mark this) moved upon the waters (He stirred the foggy chaos, drove, compressed it into narrow bounds so that it had to resolve within itself and become watery and thick), and further, at the almighty powerful word, “Let there be light!”—that the light came forth out of the darkness, and that the light was good; and thus, further, that “evening and morning” became the first day.

What could be set forth more plainly to explain and portray our true Stone?

One might answer me here and say that indeed, by this, one can recognize the first matter of our Stone; but how to proceed further with it—of that numberless books have been written, yet for the most part so obscurely and with veiled words that one can understand the least part thereof. To this I reply that in truth it is so. Therefore, my dear reader, do not imagine that you can gather fruit from an untilled land; first it must first be dug through with hoes and mattocks with the greatest toil; then, after you have sown your land with a proper seed (in which the little germ is not dead, but still green and living), it will, by the early and the latter rain, also bring forth fruit. Of this you can learn from the farmers and take an example from them.

But that you may also have from me a quite plain explanation, know that I have resolved to write as open-heartedly and without deceit as none has yet done. True, there are very many who boast of this—especially the noble Philaletha, who makes such promises that one might think one would find with him Diana naked and wholly exposed to the eyes. He also boasts himself to be at the very core of alchemy and affirms that he reveals everything and withholds nothing, one thing excepted; but I say in truth; for I have experienced it: whoever is lacking even this single One will surely miss the mark.

In Eckhart’s Entlaufener Chymicus, speaking of the earth, he says among other things how d’Espagnet resolved for him the doubt which he had concerning the Doves of Diana, and which for that cause had occasioned him so many restless nights; yet the name Diana still stood in his way, until at last he learned that the ancient philosophers often imparted one name to two subjects—especially the Egyptians. And when he further considered that the nymphs are the team of Venus’s chariot as well as the doves, and that these are the team of Diana’s chariot just as those are of Venus, he finally came upon the right road. I must confess: whoever rightly understands this, to him the single One cannot be hidden. But that one should rely upon d’Espagnet with clear, indubitable one could find this from d’Espagnet’s words—let him who pleases to seek it there experience it for himself.

For what great toil and hardship it costs to pick this kernel out from the coarse chaff, those can tell who have exercised themselves herein. To investigate Nature, to discern the pure from the impure, is a labor not only of the body but also of the spirit; it is a work that occupies a man’s whole mind and brings it into the greatest unrest; a work that also requires a whole man—I say, a whole man—one who has not dedicated part of himself to the world, with too much commerce of worldly company, nor imagines that he will erect for himself some great worldly dignities (which indeed may go by one name or another). All this I find quite unnecessary to touch on here, since this has otherwise been sufficiently set forth by others.

To sum up briefly: it is enough for the one who longs for wisdom to know that this is the right course—that each remain in his own station and, as far as possible, withdraw from all worldly company. Nor must such a person at all times look only to profit; rather his desire must be to behold the great wonders and unfathomable works which God has laid in Nature and to take delight therein—sparing neither toil nor labor, which are to be met with here in many forms (especially in our first conjunction of Venus with Mars, her consort). He must not look upon this only in one way, but both by night and by day spare no effort, however great it may be; rather, with might and strength press on through this rough, untrodden path, beset with many branches and hindering detours—this toilsome, climb up over the cliffs and not relent until one can reach the harbor of desire and the shore of blessedness.

Finally then—although one has obtained this glorious jewel and has the treasures of this world in possession—one should not refuse to cast everything once more at the feet of this world, and to live with God for eternity; which eternal blessedness and highest delight I will not presume to express with this pen, but may the Lord, the Lord Himself, with the finger of His holy good Spirit, write and engrave the same upon the tablets of our hearts, so that we become ever more fit to tear ourselves loose from the strong fetters of these monstrous chains of the world, and with the wings of our spirit soar upward into the heavenly places, where we shall triumph forever with God and in God.

But so that I may also come to my promise and put it into effect, let the kindly reader know that we must first understand for what we wish to use our Stone. Since my intention is to treat of a Stone that is to improve the metals, it follows plainly that one must not seek it among things that are combustible; for Nature does not allow it to be found there, nor can anyone bring its like to any increase except upon the nature of its like. Therefore it must of necessity spring from and flow out of a metallic root.

Thus this Stone is generated nowhere else than from its own seed. Whoever therefore loves this wisdom and would search for this golden star must, before all else, go with the Magi near Bethlehem, where this new-born King lies and may be met; follow it, and you will then find in a single subject the philosophical ground and root in which all three—spirit, soul, and body—lie hidden, with which the beginning and the means of the work can be brought to a happy end.

Whoever learns to know this seed and its magnet, and to investigate its properties, may truly boast that he has the true root of life—the single root of all metals and minerals—and at last will find that for which his one desire has stood in this world. In short, he will climb to the highest summit of Mount Parnassus and, in the garden of the Hesperides, be able to pluck the apples to his heart’s content.

This our subject—our magnesia, our adrop—must, at the beginning of this work, be most thoroughly cleansed; then opened and broken open and made into ashes; for the philosophers say: the artist who has no ashes can make no salt—a saying full of truth. Whoever therefore knows the salt and its solution, as well as the coagulation and distillation, knows the secret of the philosophical tartar and the whole foundation. Yet this salt is of no use unless its inmost part has been brought forth and reversed; for it is the spirit alone that makes it living—the mere body avails nothing here. He who has this spirit has the salt also.

Here I have spoken much; I wish the beloved reader may understand all this in its proper force. I say in truth: whoever does not understand this still has a great veil before his eyes, and it would be desirable that he should in time desist from his dangerous journey and turn back again; for I say in truth, and I speak from my own experience: if someone, in foolhardy fashion, should set out on this dangerous, untrodden path, it may well happen that he is attacked by the untamed wild lions and poisonous dragons that lie along the way—creatures not always so firmly restrained that they cannot at times inflict on the passer-by notable and irreparable harm—so that he is assailed to the point that he is no longer able to turn back, much less to go further. For what is our matter other than a poisonous dragon?

What else is it than a wild, unbridled lion and a life-destroying basilisk? Yet far be it from me to teach that this our initial matter, or the taking of this road, is harmful to everyone—no, only to those who, without preparation and without sufficient prior knowledge, rush headlong upon this and stony, mountainous road; for it can easily happen that these inexperienced folk catch sight of some side-path—of which innumerably many are to be met—and think it not so altogether unreasonable to take it. There too they come upon one or another “marks” of which the guides have spoken; and it may finally seem to them that on such by- or side-ways they would meet with less danger and trouble than upon our untrodden way.

But they should be warned that, before they ever come to the end of such a road, they will have to learn—regretfully—what it is to undertake a work for which one has no foundation. For what could be more wretched than those who, having spent most of their life in unjust usury and in forbidden speculation and hoarding of all manner of wares, when at last they have ruined themselves, now wish to take up “chymie” imagining that the same “understanding” or cunning which had served them in their injustice (and which had nothing but the nature of the venomous serpent, and by no means the simplicity of the dove) should also suit this heavenly science.

Oh no, indeed! They must surely learn—though late and with regret—that chymie is pure fire, and whoever thrusts into it rashly will be badly burned. It is like water: whoever plunges in without first being taught to swim will surely sink deep. Therefore I say once again, by way of warning: test yourself well beforehand; for it may be that at the Chymical Wedding one will be set upon the scale, and in the balance one will register as sheer nothing, unable in the least to move the weights that are set thereon; for this is a matter such a matter that is not to be handled by every unwashed hand; the noble growth of pearls is by no means a dish for swine.

Let every rash boaster—whose pen no longer suffices him, who would continue and practice his customary day- and night-long debaucheries—know that this science in no wise accords with him. For what fellowship has righteousness with unrighteousness? That has long since been answered. In short, such people should not imagine themselves fit for these things; they belong to far subtler minds than are found among such world-roamers.

Whoever therefore wishes to be spared the mockery mentioned above at the Chymical Wedding must first acknowledge the rudiments of nature; for how could one learn to read rightly to whom the letters are unknown? He understands not at all the musicians who has not first learned the notes.

It is truly pitiable when one must so often hear from the so-called chemists that this or that fellow “has the art,” that he can bring so-and-so much upon this or that metal; that he has (to use their own mode of speech) a real particular, a good “in- or out-bringing into Luna”—at which a man who can at least distinguish white from black has his ears made sore. Then some peasant—who would be far more praiseworthy to remain with his cow-milking—must needs be master of the Art. Why?

Because he has read the books of the German philosopher Böhme; and since in those books (which I esteem each in its degree, and which will still give a wise man enough to do to understand those profound writings of Böhme) very many strange signata are to be met with, which in the end every peasant—as one also finds such things in an almanac—can still read this man’s writings, wherein there is no particular art; and then they say: this peasant is so clever that he even understands the whole course of the heavens! And there are those hearts that fancy they have swallowed all the world’s wisdom (though these mockers ought to be ashamed to touch with their venomous tongues men to whom they are not worthy even to loose the shoe-latchets), yet they are pure fools compared with this peasant.

O misery and lamentation! But—my dear “particularist,” or my good peasant!—being able to read and being able to understand are two different things. It by no means follows that if a peasant can read and write, he can therefore at once understand everything—which is why such excellent men have sometimes written in flowery and ambiguous words wrote so—not in order that their true followers, who have all taken the yoke upon themselves and have not shrunk from bearing it along these rough and trackless ways, through hardship and toil (on which road, to be sure, peasants would still be very apt to stumble), should be unable to understand; for why should the true philosophers hide anything from their children?—they are precisely those who belong to this heavenly art.

But from those coarse fellows (I am compelled to use Basil Valentine’s words) it had to be kept back until illumination and knowledge should afterward follow; thus the wise have indeed concealed their high wisdom. And because everything—even the divine Scripture—is readily misused, it is said that to the wise and prudent of this world these lofty mysteries are hidden, but to the simple and the unlearned God will reveal these high sciences.

Yet alas! O folly!—the simplicity and childishness spoken of here, which by no means is to be overthrown, does not consist in a mere pair of peasant’s breeches. If that were what counted, there would be many who, to their great advantage, would simply change their dress; the chymists and alchymists would all come forth clad in peasant garb—and doubtless the Swiss peasant dress would be judged the most convenient! No, this simplicity consists in many other things.

Shall I name them? I will set them before you only in David’s 15th Psalm—there you can read them; and believe me, it will be far more profitable and useful to you than if you were to leaf through all the books of the blessed, highly enlightened Böhme, and look at his signata as a cow stares at a new gate, like fool or like a blind man judging of colors. In truth, those profound writings belong to other sorts of minds, and it was by no means that blessed man’s purpose to instruct the whole world in chymie; he treats of something quite different. Whoever can understand those writings will indeed be led by them to a great knowledge of himself.

Therefore I kindly advise peasants in general to remain by their plow, and instead of these deep books to read the Testament diligently. Yet I would not like to be regarded and taken as if I said this out of contempt for simple folk; one would certainly do me wrong to attribute that to me. For it is not unknown to me that God raises the lowly from the dust and sets them among princes; I also know well that God resists the proud, but gives grace to the humble.

I also know that the Lord God teaches the afflicted His ways and instructs them in His secrets. It would take far too long for me to add here everything that has been promised to the righteous. I speak only by way of rebuke to those who lay claim to these lofty mysteries and yet are full of ignorance—a fact that would surely come to light were an examination to be held. I have said above that true simplicity and childlikeness consist in many other things. In short: whoever does not understand Nature should leave these mystery-laden matters alone, or else he will have to pay for it to his own harm.

Here I cannot, in passing, leave unmentioned that nowadays among the clergy there are some who presume to do so—to practice both in medicine and in chymistry—which is altogether irresponsible. For a bishop ought to be blameless, not to involve himself in strange occupations, and not to ply a trade. God the Lord expressly commands in chapter 18 (of the Law) concerning the Levites that they are to attend to their office at the tabernacle, and that they are to possess no inheritance except the tithe; this God has given them for an inheritance, together with the promise that God Himself would be their portion.

But the priests of our day—so-called “Levitical” priests—are not content with this: they boldly lay hands here and there on an office that is not theirs. It seems to me that the strange fire of Aaron’s two sons (if, indeed, they believe there ever was an Aaron with his sons) ought to hover before their eyes like a threatening rod. But alas! O eternal God!

O God! In what a miserable and pitiable state the clergy stand today. Where can one find true and faithful shepherds who make it their earnest care to tend their flock—who heal the sick, watch over the weak, bind up the wounded, bring back the strayed, and seek the lost? Must we not rather lament that, for the most part, there are shepherds who pasture themselves, eat the fat, slaughter the well-fed, and clothe themselves with the wool, while they let their entrusted flock wander utterly scattered—so that at times they are miserably torn by wild beasts—and there is no one who takes heed of them?

I ask you, O shepherds! What sort of “beasts” do you think they are whose blood will be required at your hands? Do you suppose you can answer for yourselves when you only deliver, at fixed times, a lukewarm sermon about, from the pulpit and leave it at that, offering no further personal admonitions from yourselves?

Do you think—tell me—that with this everything is set right and you have nothing more to do for your flock? (I will pass over that you ought, with all your ability, to order your own manner of life according to the Word you preach—unless you wish, through your own negligence, to be blameworthy—so that teaching and life agree; but where are such men to be found? scarcely anywhere.) Do you not know that private instruction can often do as much good as public sermons, which—alas!—are delivered merely out of custom? Why do you not bestir yourselves to deal with this person and that, whom you know live in discord—where the weaker is most cruelly oppressed and persecuted by the stronger, and the godless harass the devout seek to swallow them up by every means and way—should you not in particular punish this? since it is your office; and you cannot slip out of it, unless you wish to be held outright as weaklings.

You ought in earnest to warn them to turn from their evil, perverse life—to root out of the heart (which should be a temple and dwelling of the Holy Spirit, not a loathsome cesspit of devilish vices) all hatred, all envy, every bitter, often twenty years and more old, rancor. And with such people—should it even happen that these malicious enviers and persecutors are your own blood-relations, yes, even father, mother, or nearest kin—show not the least partiality or hypocrisy; in this matter, namely in punishing vice, no person is to be regarded, but everything is to be dealt with plainly and thoroughly, whoever it strikes, let it strike—use the sharp, two-edged sword of God’s Word; then he would prove himself to be a true prophet and teacher sent by God, one whose mouth the Lord has touched and into which He has placed His powerful word.

But alas! If one were to walk today through all the streets of Jerusalem, would one find such teachers and preachers whose heart is so disposed that they ask after the faith, do what is right, consider the ways of the Lord, themselves walk in His ways, keep His commandments and law, and also teach others the ways of the Lord and, as their office requires, instruct them in the same? Ah, no! For they have all turned aside; there is none who does good—though they ought well to know what purity and cleanness of spirit, and what perfection of life, are of life—which the priests of God ought to have in them.

We read of Joseph that when Asenath, before she had been given to him in marriage, drew near to kiss him, Joseph answered: “It is not fitting that the one who eats the bread of life and drinks the draught of immortality should touch the mouth of one who eats from the sacrifices of idols.” Thereupon Asenath earnestly strove, according to Joseph’s instruction, to believe in the true living God and no longer to live in her former idolatry.

If this Asenath, at this single reproof from Joseph, could abandon her gods and with all her strength turn to the living God—why then would the priests of God forsake the law and commandment of the living God and turn to their own fancy, to live by that in all things? Truly, this is a thoroughly perverse matter that the heathen in all things must be wiser than the so-called Christians.

Therefore hear, you shepherds: As I live, says the Lord, because you let my sheep become prey and my flock food for all the wild beasts—since they have no shepherds and the shepherds do not inquire after my flock—behold, I am against the shepherds. I will demand my flock from their hands and make an end of them, so that they shall no longer be shepherds nor feed themselves. I will rescue my sheep from their mouths so they can no longer devour them.

For I myself, says the Lord, will pasture my sheep; I will seek the lost and bring back the strayed and tend them as is right. And the Lord will judge between sheep and sheep, between rams and goats, between fat sheep and lean—something that should well be considered will be judged—those goats whose time of separation will certainly come on that great day of reckoning—who in every way hunt down the sheep and trample their lawful pasture underfoot.

So the shepherds can see how much they themselves must amend before they may rightly claim that name. Indeed, even when they have done all that was commanded them, they are still unprofitable servants, far removed from the perfection of their chief Shepherd, their Lord and Master.

From this it is clear with what disorder and injustice they presume to take upon themselves things that, in view of their office, do not in the least belong to them—though I speak here only of some; for I am well aware that there are also teachers and preachers who uphold the Lord’s rights with all earnestness hold the Lord’s cause in earnest, cling to His testimonies, and have chosen the way of truth—whose souls long and whose eyes yearn for God’s command; who also restrain their feet so they do not walk evil paths or let injustice rule over them, but early root the wicked out of the Lord’s city; in a word, who do not turn aside from the statutes of their God but make them their eternal inheritance)—why should such men busy themselves with matters that are not only wholly unseemly for them but far beyond their understanding? Why should one who is set apart to preach the Word of God meddle in things he has never learned and does not understand at all—such as medicine and chemistry? Why should a preacher try to insert himself here?

Surely, it seems to me, a true teacher and preacher ought to do what he is appointed to do would have no time left to meddle in other people’s affairs; rather, he ought to redeem yet more time so that he might best accomplish everything so dearly entrusted to him and for which he must give an account. A physician studies medicine daily and watches over his patients to the best of his ability; in the same way a teacher and preacher should consider—and be diligent—how he will preach the Word of God pure and unadulterated, and how he and his household will order their life and conduct according to this Word, that he may be a living example to his hearers in teaching and in life.

But alas! what am I saying about an example? What examples do our clergy present nowadays? Are they not true examples of greed, of usury—in sum, of every self-seeking temper? Is not avarice so deeply rooted in them that they as though day and night they are bent on plotting how they might enrich themselves as much as possible; how they might heap up a treasure by which their fat bellies are filled during their life, and leave the remainder to their young. Has not usury among them grown so strong that in this they even surpass the Jews who are otherwise given to bartering? Go only to the cattle and horse markets: there you will see how excellently and how merchant-like (or “Jewishly”) they know how to haggle and bargain and trade, so that between them and the Jews (who also appear there in great numbers) no difference can be discerned—indeed, why do I even speak of a difference? The difference often lies in this, that the Jew, in justice and fairness, not seldom surpasses the so-called Christians.

O the fine virtue of our clergy today!—my pen has run on rather far here, it would not be out of place to continue further on this matter; in particular, something should be said about love of one’s neighbor and the practice of mercy—topics with respect to which the whole world, and especially the clergy, are not merely drowsy but altogether dead.

Indeed, so much so that, if one happens to engage them in discussion and begins to speak of love for one’s fellow human, it seems to them as strange as if one were talking about “Bohemian villages.” One will even hear them laugh out and say, “Ho! the shirt is much closer to me than the coat.”

Yet I am not inclined, in this little tract, to go so far beyond the proper bounds—as, in this point, has almost happened against my will. Let this brief mention, namely of love and mercy, therefore be taken up at greater length in another treatise, I will expand on this more fully elsewhere; for the present it is enough to have heard how, alas, greed, usury, and self-interest have seized our whole race. In order to conclude my former point more fittingly (namely, that today’s “Levitical” priests intrude into a foreign office), I say this: it would be very ridiculous to behold if a sacristan or bell-ringer presumed to preach to an entire congregation from the pulpit.

In like manner, it seems to me far more ridiculous when one must see that a man who ought to be a teacher and preacher busies himself with medicine—or even more with alchemy. These are not matters that belong or harmonize together. And what does such a so-called teacher and preacher reveal by this? Surely nothing else than, besides his great ignorance, his great, insatiable greed for money—which is then a great blot of shame of the preached Word of God.

It would also be only right to take to task those who presume to revile this noble art of alchemy and, with many mocking speeches, try most slanderously to besmirch all who work at it (I mean those who, through diligent inquiry into nature, have laid a lawful and irreproachable foundation), as if they were busy with unlawful things. People say, to be sure, that many have ruined themselves by it, and that it is nothing but pure delusion and empty nothingness. But who can, I ask, keep silent while such ignorant folk gnaw away at the good and honorable name of wise men?

Who can patiently listen, I say, to the blind daring to speak about the sun?—though it is more praiseworthy to despise useless prattle than to refute it; nevertheless, let such people know that I have no time to dally with them; it is useless to try to cure every man of his folly.

I refer them to Irenaeus Philoponus Philalethes’ Kernel of Alchemy, where they will find ample material to correct the smug prejudices they pass on against others—prejudices they are in no position to answer with even the slightest well-founded counterargument—so that, unless they are utterly stone-blind, they may convince themselves.

Our innocent philosophy is free of vice and stands unmoved, for it is firmly established upon the solid pillars of this truth and, to our comfort, can remain protected against the barking of these envious rams. Therefore I am by no means inclined to expend great effort trying to instruct the ignorant in a path which they could never learn to walk, not in all eternity.

My purpose is only this: from my heart I would wish that the true lovers of wisdom might, by means of this little instruction of mine concerning this excellent secret, gain a firm foundation and in due time turn away from the errors that have hitherto clung to them.

For in truth I find that my intention is so Christian and honorable—since I myself once wandered long upon my own erring paths (indeed, perhaps up to this very day I should still be found on them), had not the most high God taken pity on me and sent me a faithful guide—whom I shall revere from the inmost ground of my heart as long as I draw breath, and toward this most faithful guide I shall show all due respect with the most obedient humility. From his brightly burning, shining torch my little light too has, little by little, been kindled made over to the lovers of wisdom—through which I brought myself into such immense wildernesses; along them no one will be able to find the path of peace, but rather, after great toil and expense, will be plunged into indescribable misery.

Let it therefore not be hidden from the kindly reader that I too, for a long time—indeed into the twentieth year (as the author of the Kern der Alchymie says)—was one of Geber’s “cooks,” tormenting myself with all manner of brewings and stewing. At the beginning nothing was more disagreeable to me than even to hear of such things; indeed I felt an honest loathing for them. Yet I was occupied with many words of entreaty (for I found myself among people whose commands I had to carry out), speaking to certain persons—both by day and by night—to persuade them about these matters which were terribly repugnant to me; but all this was in vain, whereas those same exerted themselves to talk me into it with the most “reasonable” arguments; and in the end they succeeded quite well.

Little by little I found myself seized with a most vehement desire to set the most curious operations to work—though entirely without profit.

My first undertaking in the work was a certain mineral, which I knew how to analyze so artfully that those who were at times involved with me in the work could not help but marvel. After this, and after much reading in the best books, I took vitriol in hand, for which Basil Valentine gave me no small guidance—since in his third book On the Universal of the Whole World he treats at great length of vitriol. All this I understood to the letter, and did not realize that these wise men, by “Venus,” did not mean copper or vitriol, but rather their own “Venus.”

With this mineral—so highly praised in its rank—namely Cyprian vitriol, I spent a long time dissolving, evaporating, coagulating, and crystallizing. And after I had produced crystals (which in truth should have their six corners, the seventh being at the midpoint) that presented themselves so excellently one could hardly help thinking that by them that very star must be meant by which the Wise Men were led to the newborn King, I let them fall, in gentle warmth, into a snow-white powder in which a certain sweetness could be sensed; yet it would never abandon its nature—for the sharp vitriolic taste still had the upper hand.

This work—namely dissolving, coagulating, crystallizing, and pulverizing—I continued so long until I supposed that the external impurities had already been removed from this highly valued mineral had now been freed of all outward impurities. What remained to do was cut off the inner impurities.

So I set myself to bring this snow-white powder, in gentle warmth and in a sealed vessel, to a redness—by which turning red it was to bring out what was within and drive what was without back in. These inner feces then had to be washed away with the philosophical vinegar. After washing off these inward impurities, I planned to divide the matter into three parts—namely to assign it to a subject of Spirit, Soul, and Body—and then, after placing it in the philosophical egg, to await, in steady continuous heat, the succession of colors until the red Elixir at the end. But alas! O folly and blindness! I did not consider that whatever one sows one must also of necessity reap; therefore I had to labor—together with the loss of time and expense, and, what was worst of all, my manifold folly and ignorance—I had to lament with many sighs.

After this I turned to the metals, to draw out their oil. For a whole year I tended the lamps and withdrew, as it were, from all human company; for the companionship of even a single friend can often be enough to bring our work to ruin. Therefore I resolved to live in a peculiar solitude; all worldly things were distasteful and contrary to me, while I sought my delight in contemplating the works of nature and taking my pleasure in her wonders. Thus I practiced at this day and night, and valued watching my furnaces far more than the company of my best friends.

Yet despite my constant, diligent labor, all this came in the end only to a result that I must repent and yet in truth I could by no means lay the blame on any mistake in the operation or manual handling; for I had a master who understood all the works of chemistry excellently well. But we were like those foolish people who, when they wish to graft a tree, break off a few little twigs here and there, imagining that from this a true tree should grow; or like someone who would take a few parts of a human being—an arm and a leg—thinking a well-formed man could be made from them. Though such examples are so plain that even simple children would know better, and it is quite unnecessary to instruct sensible, mature people with such coarse comparisons, yet in fact and in truth it is so that most alchemists of our day, who imagine they understand Nature, and busy themselves with such and similar things—as those crude examples show.

But if they truly understood natural things, they would take counsel with Nature herself, diligently observing her precise and orderly works; for art follows close upon the heels of Nature. If now one undertakes anything that runs contrary to Nature, art soon comes to an end.

With these vexing and useless labors I tormented myself, as said, for twenty years before I came to a true understanding; and the beloved reader is warned by me—out of a truly Christian and brotherly good will—to beware of metals and minerals, whatever names they may bear, be it gold and silver, and likewise the other metals. Among the minerals let him beware of vitriol, antimony whatever names they may have; he should also beware of quicksilver (mercury).

In sum: all these things—both the metals and all minerals (none excepted)—are absolutely of no use for our work, which I solemnly attest to be true.

By these statements of mine, all of them truthful, the opinion of truthful men is by no means overturned—namely that of Philalethes, who attests that the matter one must take in hand is, without any doubt, the Mercury and the Sun. This is surely, and in the highest truth, the pure, clear, unadulterated truth; and this man has kindled no small light for the world. But by this is not meant the common quicksilver; rather the Mercury and the Sun of the sages, in which there is a notable difference—indeed as great as that between day and night; for why should these wise men who have all attained this heavenly wisdom by sweat and hard labor, who at times in restless nights have had to break out in sweat. For not only the much-beloved Philaletha, but many others besides (as I too can testify, since this deep inquiry has often cost me my sweat), must admit this.

Should they present everything so neatly and publicly to a base and ungrateful world?

That would be wholly against the laws of the philosophers, who laid a curse on anyone who would presume to call the matter by its proper name. But to their sons, their children—who, together with heartfelt invocation of God and with unceasing, tireless work and diligence (despite the wicked world’s persecution and snares), tread in their footsteps—to them they have indeed written so clearly and so candidly that I would wish, I should like to have the chance to acknowledge such faithful teachers with the most grateful heart.

I have said truly that, to prepare our Stone, one must abstain from all metals and all minerals; and just as this is true, so it is equally true that plants and animals are wholly unfit for this work—for, as has been said, one reaps what one sows.

But I have already stated above that, since our Stone is to be used for the improvement of metals, it is therefore necessary that this Stone be brought forth from a metallic seed. Therefore, my most dear reader, look carefully about to see where you might find such a seed, such a foundational moisture. Basil Valentine, a man who indeed writes in a deep style, treats in the in the book On the Great Stone of the Most Ancient Sages so excellently on this matter, that I am amazed so many highly learned men have achieved so little in it.

But, as already said: this is a thing that must be asked of the Most High God, for His unbreakable seal lies upon it. It is impossible to obtain it unless a person first enters into himself and learns to know himself; moreover, he must rise up out of himself and out of the world again, and come into God—only then may he entertain any hope of this blessed Stone, otherwise not.

Meanwhile, when I saw that by now all my great labor had been in vain, I resolved to seek this high secret in quite another manner. I considered the vanity and nothingness of this world—how wretched and blind a man is, although he knows that this life is but a handbreadth long, and nothing else; rather a pensive evening, and by no means a bright day of happiness and joy can it be called.

It is so brittle, so perishable that, when one thinks to bloom this very morning like a well-shaped rose, before evening one must be plucked and wither. And yet people strain themselves so greatly and are, as it were, occupied day and night with amusing themselves in worldly things—which is a great vanity and a consumption of the spirit. This pitiable condition of all humankind appeared to me most grievous; and the more deeply I reflected on it, the greater disgust I felt for all worldly things, and the greater was my desire and love for the heavenly.

I say in truth that I had a real revulsion and aversion to all worldly affairs; but the heavenly were my true joy and delight, in which I exercised myself day and night, then it was my delight to walk in the ways of God; His commandments were dearer to me than a thousand pieces of gold. I also busied myself with those with whom I associated daily, earnestly admonishing them—by pleading and entreaty—to turn from their worldly affairs in which they had deeply immersed and entangled themselves; but alas, for the most part this was in vain.

Indeed I must confess that in this I did not yet know how to keep the right measure in reproving vices; for I was so disposed that whenever I saw people walk in their natural way of life, striving more to live for the world than to exercise themselves in spiritual and heavenly things, I felt a real disgust and hatred toward such people, and did not at that point consider the particular leading of God and how we poor, wretched, immoderate humans can of ourselves do nothing—though I knew full well, I should have known that no one can come to the Lord Jesus unless the Father draws him.

I also failed to consider that not all can enter God’s vineyard to work at the same hour, and that there is a day of acceptance in the evening as well as in the morning. Thus it often happened that, on occasion, I did not hesitate to pass judgment on such worldly people—when I ought rather to have admonished them in a truly brotherly way, to have covered their faults with the mantle of love, and not to have ceased praying for them.

Little by little, however, I came to a better understanding: I found that it is not in anyone’s power to rid himself, by his own effort, of his natural, inborn, clinging state of sin; that the natural person lies dead in sins and transgressions and can by no means make himself alive no more than an unborn child in its mother’s womb can bring itself into the world or help itself by counsel and deed. With this recognition I received a piercing love for my God and for my Lord Jesus, and for all people; I could bless those who cursed me. My most heartfelt desire was to see the Lord Jesus with my bodily eyes, just as he walked upon the earth in the days of his flesh. I called upon him and entreated him for his grace, for his holy love; and at night I sought, with the Bride (Canticles 3), “him whom my soul loveth.” Indeed, I can truly say with the Church of God: “With my soul have I desired thee in the night, and with my spirit have I sought thee early.” Oh, how often did I break out into these words whenever I did not at once, upon my petition, have the Lord Jesus could find.

O how long, O my Lord Jesus, must I seek so anxiously? How long must I spend my days with this wish and longing? How long must I still struggle and run, until I may be set free from this temporality—yes, from this dreadful prison of the body—unto you, O Lord Jesus, into eternal liberty? Ah! I sigh and I long to be clothed with my dwelling which is from heaven; I would far rather be absent from the body and present with my Lord and God. O when shall I come there and appear before him? When shall I receive the goods my Jesus has won for me—the fruits of my prayer, the harvest of my labor, the end of my faith, the blessedness of my soul? In this anxious looking for the Bridegroom of my soul I sensed that he was standing only behind the wall and peering through the lattice, so that from this and I could have cried out for heartfelt joy: I have found the One whom my soul loves!

In such heart-refreshing delight I spent some time giving thanks to the Most High. But alas—what has such a loving soul meanwhile to expect from the children of this world, from the watchmen upon the walls, yes, even from her nearest relatives? Surely nothing else than mockery, scorn, and shame: they take the veil from such a bride; they beat her bloody; in her greatest thirst they give her vinegar and bitter gall to drink; indeed, they divide her garments and deny her honorable name, shrinking at no means of slandering her in every way, even calling her an abomination before the world. But alas, my Lord Jesus, what is to be done here, when such a soul, as it were, no longer even knows itself?

I know nothing remains but to stand with you beneath the Cross and cry out: “O Lord Jesus, remember me!” Then such a soul must cry and ask in lament: “Tell me, you whom my soul loves, where you rest; where you pasture?”—yet take courage, O my soul! In the midst of this dreadful persecution your soul’s Bridegroom answers your questioning with this comforting reply: “Do you not know yourself? Then go out by the footprints of the sheep.”

Meanwhile, as I found myself among these cruel men-at-arms (the great injustices and wrongs done to me—even by those who were appointed by God to protect and defend me in every respect; their shameful wickedness practiced against me compels me to speak; for they did not shrink from hiring the most scandalous and abominable ruffians to harm my very life), to regard everything that is in this world as nothing but a harm. I now desired nothing more than Jesus Christ—indeed, Christ crucified.

Then I was in a wholly blessed state; I found myself truly in a spiritual wilderness. There I could speak kindly with my Brother; there I was at times led by Him into the vineyard; there I could see how the pomegranates blossomed; there I was refreshed with flowers and fed with apples. O the great, inexpressible bliss!

But what happened as time went on? A strong desire came over me again to practice chemistry. I was now firmly convinced that, since I had first sought the things above, everything else would now fall to me as well. At first I did not press so urgently upon it, since I had already found the true Stone—indeed, the true Rock. But our ways and God’s ways are quite unlike; for God often leads us on a road we do not know.

And I can truly say that in this matter too I had to go a very rough, trackless path—through the abyss of discouragement—with the devil and all his host pressing hard behind me. That is, every day many and various arrows of slander came rushing at me from all quarters, and more than a thousand snares were set for my feet. On both sides there were sheer, unscalable mountains and crags. By such adversities I mean those of which even Solomon in his day saw no greater under the sun.

And though I was always able to arm myself with such armor as faith, hope, and patience, yet I must confess that, despite my very firm steadfastness, I often thoughts came over me to turn back from this toilsome path—though I had already climbed many troublesome cliffs and in truth overcome them—especially since, because of the fierce persecution that pressed me on the left and on the right, I felt too weak to bear such great hardship any longer. Thus there often arose within me a violent struggle; yet through Him who is mighty, who—despite my frequent great doubts—still guided me by His hand, I was able to overcome it with the greatest victory.

And lest this struggle of reason gain the upper hand with me, great and powerful giants were set before my eyes—I mean those men who in former times brought an evil report of the land. Although I could have struck them all down with a single stone taken from a shepherd’s pouch and sling, yet soon after that, many stronger enemies gathered; for there came those who would not let themselves be seen openly and dared to confront me only before my eyes—whereas it befits honorable men (I have said above in the preface what a man is) to bring forth publicly whatever troubles them. These, however, like the most venomous and harmful creatures, who practice their malice only in the dark, did not have the heart to oppose me openly, but spewed their poison against me through shameful letters and libels.

Yet, to my comfort, at that time I was provided, in the very presence of this poison poured out against me, with a preservative, by which only greater punishment was loaded upon these enemies’ necks. In this gloomy weather of persecution, however, I often had to turn against myself in to break out with these words: Should I then, on this path—now that I am utterly unable to turn back, since my whole mind, indeed my very reason, is so strongly seized by it and holds complete sway—should I give in?

Must I suffer that passers-by mock me in the most shameful manner? Are these enemies to have the glory that trees so deeply rooted could be uprooted by the mere wind of their breath? Are they to be strong enough to destroy so important a work, undertaken with long and utmost toil, diligence, and brain-breaking effort, in which God by His grace has so mightily assisted and is, as it were, commander and guide? Do these powerless men imagine that by their threats they will turn me from my intended aim? Far be it—and this shall never be permitted then someone might well imagine that, if he could possess the dragon of the East, he would—with such a timid and frightened spirit, like those who have committed a misdeed—pay heed to such obstacles and hindrances lying in the way?

Why then do we have such cowardly and fearful hearts? These words were spoken no less to that very heart of which I said above that he had been my guide, and that from his brightly burning torch my little light was kindled; for the hindrances showed themselves both toward his noble person and toward me. And although this lord would have been powerful enough to strike down all these enemies with a single word—indeed to cast them to the ground with a glance—yet his humility would not allow it; rather, he was willing, alongside me, to bear such adversities with patience and with an inborn gentleness and goodness to bear with patience; and he also gave me—as to a hot-blooded Peter—the wholesome admonition to sheath the sword, an earnest and instructive reproof.

For I might well have considered, and ought rightly to have regarded, that all these hindrances had at all times been placed in our path by a special providence, and that it does not become us to prescribe to the Most High the time, the place, and the hour—since He has reserved such things to His own power alone—and that composure is here the best remedy.

Why then do we not, with a magnanimous spirit, despise all these obstacles and adversities? Why do we not set ourselves against them with undaunted courage, and not desist until we have, with all our strength, broken through every hindrance standing in the way and have attained the goal set before us? Why does magnanimity accomplish so little among us, though it should at all times rouse us to heroic deeds—that, with God’s help, we should hazard everything we have in these most difficult matters, in order to attain so great and important a work? Why do we lie so quiet, without any stir, burying the talent and gifts that God has placed in us, when we ought rightly (yet with an unshakable humility—at which God chiefly looks, since we know well that from and of ourselves we have nothing and are nothing, though we can recognize the aim of virtue) to shine forth before others?

All this, as I said, was answered to me with the gentlest spirit and with excellent, irrefutable reasons. Yet in all this my desire grew—namely, to set my work truly to work—more and more with each day, so that I came to a veritable burning zeal in the matter. O what a longing I had at that time to set the crowned Eagle upon the throne and place the scepter of honors in his hand!

But alas! The more my rightful zeal increased in this matter, the less opportunity I had to pursue it—namely because of the godless persecutions of my enemies (I cannot call them “friends” in view of the wickedness they committed). Yet I wish them everything one may wish even for friends, especially amendment of their lives—otherwise a very heavy reckoning may follow.

At length, at last, through the special governance and guidance of God I came into acquaintance with a distinguished lord, whose nation, high lineage, as well as the supreme rank and place of residence he holds I am forbidden to set down here. But I cannot forbear to say this: his learning was extraordinary, and his favor toward me very great, which I also with a humble heart I shall acknowledge with the utmost gratitude in every circumstance, and no hindrances shall keep me from it. In sum, I will honor this lord and remain toward him in the most steadfast loyalty and in perpetual obedience as long as I live. May the Lord, the LORD, be his shield and let His grace abide over him forever; indeed, as long as heaven stands, may the covenant of God remain firm upon him! All this I wish from the inmost ground of my soul, and may heaven confirm it with an Amen.

From this lord I had the kindness shown me to read the most curious books; I could perceive in him a heartfelt joy that the eternal, merciful God had placed His gifts in so weak a vessel (that is, a woman’s form). By means of my zealous, diligent, and unwearied reading, the Most High God granted me this holy science to understand; therefore to the most-holy God are due eternal praise, honor, and thanks. I would gladly give the kindly reader further information concerning this point, but a seal has been set upon my mouth.

Yet that I may reach my overall aim and intention—to show the beloved reader as much as I am permitted by a certain allowance—I will first speak of the beginning of our matter; thereafter of the preparation thereof; third, of the first and second conjunction; and finally of the working up of our high elixir. This I will set forth by me so faithfully and candidly that one brother could hardly instruct another better or with more goodwill.

I have said that, in the search for our Stone, both metals and minerals are entirely unsuitable and in no way fit for the purpose, which is also the truth. Yet one may nevertheless say what stands in chapter 12: “And Your imperishable Spirit is in all things”—that is, in all metals, minerals, plants, and animals. But we have no need to seek this Spirit and the beginning of all things in all—or, better said, in those hard, locked bodies of the metals. Rather, Nature has set before us something nearer, in which we can seek and also find this seed.

Thus our matter is a single substance, just as that ineffable One was—before the creation of heaven and earth—invisible, incomprehensible, hidden in a substance so small. Concerning this all the philosophers write that, though its outward appearance is lowly, its hidden nature, which brings about all that is in it, grows up like a great mountain, and upon it there spring forth every kind of color of every kind.

…kinds. She is called the Lac Virginis; she is the Green Lion; she is lovely, glorious, and fair in her strength, power, virtue, and might; and she is to be found in every place. She is the true opener and closer, the penetrator of all things. She is the true signate star, the genuine medicine of the wise. She comes from a pure seed; the philosophers call her Chaos. She is precisely that over which, in the beginning, the Spirit of God hovered.

And since God the Lord, by His mighty Word—which was Spirit, indeed the breath that goes forth from the mouth of God, from which all creatures and natures have received life—has wrought wonders we cannot marvel at enough but must stand utterly astonished, that from this single matter, which, so to speak, was nothing, there have arisen such mighty creatures, with ineffable mysteries, with diverse kinds and powers, with two substances: the visible and the invisible, the dead and the living, the fixed and the volatile; also with three—body, soul, and spirit; indeed with the four elements—air, fire, water, and earth—have they come forth and sprung up; and this is planted in every kind of matter.

Thus let the beloved reader know that God Almighty, in the beginning, chose for Himself a special materia; and into it, according to His good pleasure, He has set the heavenly and the earthly, the everlasting and the temporal, and also the everlasting and the damnable, the good and the evil—joined together and sealed up. In it, too, lies the necessity, and our one sought-for materia, from which the Philosophers’ Stone and the most excellent medicine are made.

Hence one sees plainly that no other materia can anywhere be found—seek it where one will—that can accomplish our desire, except only and solely this, our single primordial materia. For it is born of so high and pure a seed—namely, of the Spirit of God. Ah, alas! who is there whose eyes and understanding are so enlightened that he can recognize that this same [matter] is endowed with such lofty inward power?

O my dear, wisdom-loving reader, call upon Him who with one word says, “Be opened!”—who opened the ears of the deaf so that they could hear the gracious, loving voice of the Savior of the world. Call upon Him who, with a little water and earth, anointed the blind man’s eyes, and he forthwith received sight. Call upon, I say, Him who made the lame to walk, the speechless to speak, the unclean to be cleansed—in sum, who has made all things well—that you too may receive enlightened eyes of understanding, and that although outwardly this is small, yet inwardly it is to be able to behold this materia, and then to separate the pure from the impure.

Now, to speak further of this materia—frankly and clearly—only so far as it is permitted. For we must be mindful day and night to conceal our Stone, lest the godless recognize it and thereby work much evil. It is also not God’s will that everyone without distinction should know this most highly blessed Stone; rather, God Almighty has revealed this high science only to some of His children—those whom He chose for it from the beginning. Nor may they transgress the will of the Most High by writing of it so plainly and calling the Stone by its proper name, such that the wicked might by it exercise their power according to their heart’s desire—this shall never be.

I can, however, assure you that the true sons of this blessed art will see everything as clear and manifest as in a mirror—an example I add here not without reason and not without particular great benefit, though only in passing.

Take this first matter—our Venus—and add to it the indubitable Mars, who out of pity for his bride will bring it about that she leaves behind her unclean garments and rises from her marriage-bed wholly renewed, adorned with heavenly raiment. This is the true sign that she has now become like those who, in the beginning before the curse, were found in Paradise.

From this there springs the Water of Life—the water that does not wet the hands. When you now have this water, you need seek nothing more, for you have everything you could desire. Oh, how precious and heartfelt this is the Water! For without it our work could not be accomplished; it is the true fountain in which the King and Queen bathe.

It is the mother whom one must bless and seal up in the womb of her child—understand: of the child that has come forth from her and is born of her. Therefore there is such heartfelt love between them as between a mother and her son; they come from one root and are of one and the same nature.

This Water of Life gives to all growing things their life; it refreshes, makes them grow and flourish, and awakens dead bodies from death to life. Through dissolution and sublimation in such a work, the body is transformed into a spirit, and the spirit into a body. Then friendship, peace, and unity are made between two contrary things—namely, body and spirit—which change their nature with one another which they take on, and one communicates its qualities to the other in every part. Here the warm is mingled with the cold, the dry with the moist, the hard with the soft; and thus there comes a complete commixture and a firm joining of two contrary natures.

Therefore such a dissolution of bodies in our Water is a true killing, and at the same time a making-alive. In this killing-and-making-alive of body and spirit, the Water must be very gentle; otherwise the bodies could not be cleansed from their coarse, earthly parts, and a great hindrance would arise that would be most harmful to the work. For you need nothing more than a delicate, subtle disposition of the dissolved bodies, which is brought about by means of our Water—provided, namely, that you proceed cautiously with your Water.

Therefore the whole work receives its purification by means of our moist Water. First through solution and sublimation; then, in such natural solving and subliming, there occurs a conjunction of the elements, a cleansing and a separation of the pure from the impure—so that the pure and white rises upward, but the impure and earthly remains at the bottom of the vessel.