Dawn is a friend to the Muses.

My fruit is better than gold yes, than fine gold;

and my revenue better than choice silver.

Proverbs 8:19.

The center of all things.

I praise.

I open.

Description

of the secret of the Philosopher’s Stone,

from

the wisdom of King Solomon, illumined and preserved by God,

to the honor of God;

described by one

who in the dew sees the mighty works of God.

Frankfurt and Leipzig.

To be found in the Krauss bookshop. 1774.

The Golden Rose - Güldene Rose,

that is,

a plain description

of the greatest secret, laid into Nature by Jehovah, the Almighty Creator of heaven and earth, and allotted to His friends and chosen ones

as a mirror of divine and natural wisdom

brought to light

by J. R. V., M.D.

To the most serene, most mighty Prince and Lord,

Lord FREDERICK the First,

Extracted and Translated to English from the book:

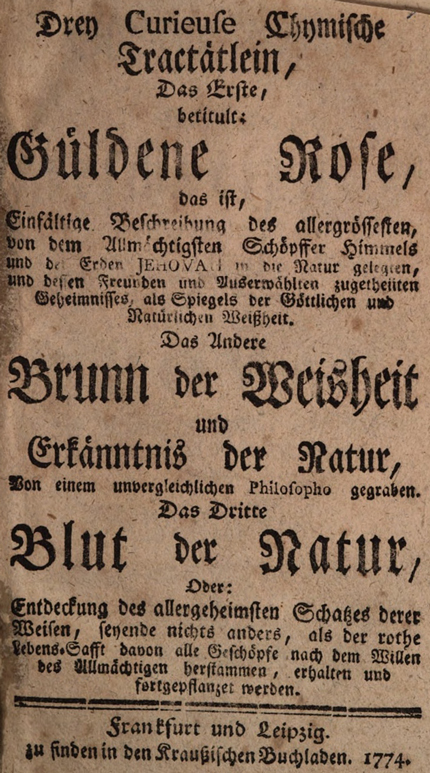

Drey curieuse chymische tractätlein, das erste, betitult: Güldene rose, [das ist, einfältige beschreibung des allergrössesten, von dem allmächtigsten schopffer himmels und der erden Jehovah in die natur gelegten, und dessen freunden unhd auserwählten zugetheilten geheimnisses, als speigels der göttlichen und natürlichen weissheit.] Das andere Brunn der weisheit und erkänntnis der natur, von einem unvergleichlichen philosopho gegraben. Das dritte Blut der natur, [oder: Entdeckung des allergeheimsten schatzes derer weisen, seyende nichts anders, als der rothe lebens-safft davon alle geschöpfe nach dem willen des Allmächtigen herstammen, erhalten und fortgepflanzet werden.]

King in Prussia, Margrave of Brandenburg, Arch-Chamberlain of the Holy Roman Empire and Elector, sovereign Prince of Orange;

Duke of Magdeburg, Jülich, Cleves and Berg, of Stettin, Pomerania, the Kashubians and Wends; and likewise in Silesia, Duke of Crossen and Schwiebus;

Burgrave of Nuremberg; Prince of Halberstadt and Minden; and Landgrave of Hohenzollern, of the Mark and Ravensberg, Lingen, Moers, Büren and Leerdamm;

Marquis of Veere and Vlissingen; Lord of Ravenstein, of the lands Lauenburg and Bütow, also Nielan and Breda.

To my most gracious King and Lord.

Most serene, most mighty, most gracious King and Lord, Lord.

Why, most mighty one, must I here at your feet

lay down this chymical poem in humility?

I asked Hermes himself, as is fitting,

who at once gave me the following reply:

A royal treasure, begotten by Sun and Moon,

surpassing the power and riches of all treasures;

it has itself chosen a place upon emerald;

of it the kings are most fittingly told.

A lord who rules land and people by God’s counsel

he is in truth the one to whom such a treasure belongs;

and he who, in God’s stead, provides for the land’s peace,

To him it truly belongs before all others.

Now, great son of Prussia, you image of God on earth,

as Jehovah himself speaks, I can become so fortunate

that the radiance of your beams shines upon this page;

thus the aim is attained at which I have aimed.

What God has laid into Nature as powers,

what the realm of metals, wondrous, contains within itself

yes, what the guild of the wise writes of the Great Work

is incorporated in the following poem in plain fashion.

Although I do not boast of having already attained it,

nor of being in possession of such rare gifts,

yet what has been written by the hand of wise men,

and what Nature teaches us, I here make known.

Can Nature do something, so she goes these ways,

which I place before your eyes in what follows,

However far art and practical skill may reach,

this poem does not bring it forth into the light in darkness.

But since something may still be lacking in it besides

which Your Majesty, of grace, can supply to it

therefore my hand yes, pen, heart, and mind

I, great FREDERICK, lay at your feet.

The Prince of kings, the pure fountain of wisdom,

the Master of Nature, JEHOVAH,

make clear what is now dark, and grant if it please Him

also to Your Majesty the jewel of this world.

May virtue, peace, and fidelity flourish in your days,

and may everyone inquire after God’s Name;

may righteousness Jesus himself

look down from heaven upon us to restrain Satan’s cunning.

So live in a realm of peace, most mighty one in the land,

What your hand governs, I may, according to my station,

call myself your servant; thus I lay down what I can

of art and learning for your service.

Most serene, most mighty

King and Lord, Lord,

Your Royal Majesty.

Hamburg, January 1708.

Your most humble and obedient servant.

Address

To

The true Children of Wisdom.

Well then! Children, arise you who walk in the light,

and love true wisdom mark what is now being done;

you investigators of Nature and of true medicines

which God has created up! make yourselves ready!

Come, behold the glance that Wisdom grants you;

do not despise the ray, by which you are able to see

the wonder of Nature, to which wisdom belongs.

If one would recognize it, mark what is taught to you.

At first you must, with the greatest diligence, consider

what is imperishable; then direct your senses

to that which brings all things to fair growth,

and from the central point presses out to the outer circle.

For this power is great and full of wondrous works:

a living fire and the strongest of all strength,

which destroys all might; a light full of clarity,

which breaks through the darkness with all its powers.

But what this thing by name may be called,

that will I show you in these writings:

mark it in one word it is the fiery Mercury,

who in the work of creation drove forth into freedom.

He opens and shatters; he kills; he makes alive;

he binds; he overcomes; he makes volatile and steadfast,

He transforms whatever he meets according to his properties,

and gives to every thing the power allotted to it.

In this fire-spirit all power lies hidden,

by which the dead body is wholly awakened;

the first man too received his form from it,

and stood most highly adorned with manifold colors.

This is that very lump from which the first being

also took its beginning, and nothing can be healed

unless the ground is turned up from it;

otherwise it remains forever as a dead earth.

Thus this thing now consists only in two things,

from which it is taken out, as our wise men sing:

the heavenly nature and high spirituality,

and thus, in such measure, eternity out of time.

What now the great world plainly lays before our eyes,

And, hidden in the earth’s depths, it is nourished;

each has its share of it, and within itself.

Yet the little world also passes over you and me,

for it surpasses the riches of this earth;

otherwise no thing at all could be made comparable to it.

God himself placed in it the heavenly pledge

the eternal light, known to few.

Therefore the little world is full of balsamic powers;

it ever distills from itself the purest juices.

A salt-spirit gushes from it, which makes it perfectly pure

as the white bears witness, which suddenly became stone.

My Jesus, God’s Son, gives fine teachings about it;

whoever will only turn his mind to this ground

can easily perceive why the earth’s salt

So highly it is praised with its sweet fatness.

Mark, and understand rightly, what is here indicated,

and that one guides you only by parable;

but God gives the spirit for wisdom and understanding.

Turn your mind to it; stretch out your hand to it.

The names of this thing these are not to be counted;

once you have recognized it, you may choose for yourself

what you wish to call it: the thrice-twelfth number

gives you the right word; now I leave you the choice.

Gold alone resembles it, and comes fairly near to it;

and yet it is not gold, as the wise man saw:

he rejoiced greatly he thought in his mind,

“Where shall I bring this treasure in the Isle?”

I dare not command this measure to the rich;

the poor man can count it for himself by shocks,

for the one does not heed it, and the other has far too much;

yet I do not throw it away it serves me for sport.

Mark: the son of this thing is cast onto metallic bonds,

and is cast back to me again with a gentle fire;

it yields its juice for a prey,

and takes it again with weighty gain.

Yet it must first die itself the bitter death

before it can inherit the power of heaven.

Then it is our stone, vessel, the oven, fire

the key of our art, both wholesome and also precious.

Therefore at first the red lump of gold

does not serve for this high work,

until it has full, the greatest strength.

has attained perfection; then it unlocks the gold,

and distributes richly from the servants their pay.

Perfect is the thing according to its first being;

yet more perfect it becomes when it is once healed

from the suffered death then it dies no more,

and rules eternally, as all the wise teach.

This, then, is the Mercury whom all the wise love

not the common quicksilver, the sixth among seven;

for that would be far too base this comes from that one,

that one originates from itself; ours is drawn from us.

With this fire-spirit wonders are to be accomplished;

he is wont to settle all strife in Nature,

to unite water and fire, to dry what is too wet,

to moisten what is too dry, to burn up what is exhausted.

In sum, his power is not at all to be fully fathomed,

and it is a strange thing, which few can find,

which is known equally to all mostly taken for granted

and yet it often proves very inconvenient to many.

Nothing can stand before it; it devours what it begets,

And makes alive again what inclines toward death.

To the eagle it is the same: it mounts up to heaven,

and again heavenward out of its deep grave.

The instrument of Nature, by which all things live

this is the one thing for which men strive,

and it remains forever the true ground of wisdom;

the Most High be praised for it every hour.

JESUS.

After I had for a long time, with care-laden sorrows,

traveled through many lands, from evening toward morning,

at noon and at midnight, to see whether I might one day find

the great treasure of the world yet I never attained

the true track to the throne of wisdom.

Everyone tormented me, and I could take it as a foolish ape:

whatever inclination toward this path I showed, I was laughed at;

I was sent farther on, made a fool here.

Nor could the comfort of the mockers turn me aside;

I remained ever intent on completing the journey,

The one who leads to wisdom I mock the fools

and their fool’s manner, and did not look behind me.

I hastened on unshaken, left the old being,

since I had first chosen the treasure for myself;

for I clearly perceived the mockers’ vanity,

which brings no profit and only wastes time.

I turned toward wisdom and sought it with pains;

it is easily extinguished, although in my heart

there was still thick darkness and idle madness;

yet I became more inflamed and sensed the danger

that befalls all mockers. I read, I rested, I pleaded;

I sighed anxiously; I took Nature for counsel

yet not this alone: I besought the great God

that he would, according to his counsel, change my need.

That was the true way, which at first I had missed,

and often rushed past; therefore I too was often ensnared

the uncommon pledge to the noble throne of wisdom,

where true virtue’s diligence attains the crown of honor.

God heard my prayer; he saw my hot weeping,

and graciously let the sun of joy shine for me;

his angel led me to the true mountain of peace.

Where pure wisdom wells up, where honor, power, and strength.

This was Raphael, who led me to the spring,

to the spring of Nature, where evil and good feed,

and are often so deeply mingled that no separation holds,

even though the green lion roars with full throat.

Here I truly feel the grace of the great Creator,

in that the host of the wise, with a black “load,”

came straight toward me the key hung from it

by which the whole art can be learned.

An old man beckoned to me, at which I was alarmed,

whereupon the whole host at once blew upon me:

“Son,” they said, “take here the key to the art,

which God bestows upon you out of pure grace and favor.”

At first I was very afraid and took it for a ghost;

but my Raphael says: “Go and bind yourself

to be faithful herein.” I swore, and committed myself

as a faithful servant of wisdom heart, mouth, hand

and am now myself far more content from the heart,

since the stone of the wise lies before my eyes;

for through the power of the thing I pierce through all things,

Before I sing to my God praise, glory, and honor,

then the scales fall away from my dark eyes.

Now I can draw the arts from the breast of wisdom,

for God’s goodness gives blessing and understanding,

so that I comprehend in the ground what is known to few.

Not that I, with this, exalt myself over God’s high gift,

and what I otherwise have from Him and His grace,

out of pride no! It is God alone:

what I am and can do, His servant I will be,

and I will praise only, only the great God

as indeed it cannot otherwise stand with me.

For I am earth and dust, a true child of sin,

a truly unprofitable servant, as all men are.

Hear, mockers, mock on! I can endure it all,

since I can pasture myself by the spring of wisdom.

And I wish that your heart might be opened by God,

that you may recognize the false masters’ delusion.

For whoever is granted this grace again by the Most High,

that he turn back from the crooked path of false delusion,

He seeks, in time, and God, the path of wisdom:

blessed is he who can grasp this word in his heart.

The art is true and plain; with it there is not to be found

what flatters according to lies; it is not to be grounded

in its deep basis; with God, Nature, and Scripture

it agrees rightly as he knows who hits upon it.

The other is called deceit, a poison, sophistries,

which is easy enough to notice, since people are wont to cry:

“Here is wisdom’s treasure! here is its sweet bread!”

But do not trust it: their bread is hell and death.

It is a foolish “white,” mild, knowing nothing,

yet it can deceive;

it always aims upward; most take delight

in its opinions, swear by it,

and miss by far the golden door of wisdom.

Therefore look well around you for the seven pillars

with which wisdom builds, what she is wont to distribute.

Her bread is sweet food; her drink is milk and wine.

Blessed is he who can always be about her and her table.

Here flows the sweet spring, the juice of the clear stars.

If you wish to learn the way to it with good use,

then know that it is very hard to come upon the track,

unless you can truly sense Nature.

You must be a hunter if you wish to catch this hind;

that toward which an upright heart bears upright desire.

Therefore the sluggard perishes, lays his hands in his lap,

and does not care, though he knows well that he is poor,

naked and bare.

Therefore gird yourself, you hero, and now begin to hunt;

do not follow only the wind, as all hunters say,

otherwise you will miss the track and the black wild,

which falls to you only with little effort, luck, cellar, soil.

If once you have the track, then you can stretch it out

through the help of Saturn, around all green firs;

to hunt the silver-white roe with force,

that mountain and field and valley may soon yield game.

This is the moist bride, the quarry of a day;

therefore do not trouble yourself in vain with heavy sorrows.

Saturn catches her for you very easily and very soon

through the power of his net, for then he has the mastery.

The cunning thief can lead you onto the meadow,

so that you can enjoy the maiden, faithful and dear;

but guard yourself diligently against Cupid’s arrow,

otherwise you will come far too late to this great salvation.

Above all, see to it that you stand well with God,

and walk on his ways without wavering;

for without his counsel all counsel is in vain

no running, no striving avails: the art grants no favor.

One thing I will tell you: God gives into your hands

this wondrous thing; see that he sends with it

the black gardener then you will receive from the hand

of the Creator of this world this pledge.

This is the true ore and mine of the metals,

the wise men’s single flower, the fairest of all

a seed of the metals, very lovely, white and red,

mostly black, gray, green, and it helps in every need.

This thing is of animal kind; it gives the powers of flowers;

yet it is also metallic, accomplishes its work

in Nature’s growth, and is in a triple form.

If you do not understand this, you will hardly grasp it.

It is no mineral, no herb, nor anything of animals,

For these will only lead you into ruin:

metals are of no use nor fumes or sulfur,

ore, nor “letten” (clay/mud), salt, still less mercury.

Not that you should not diligently seek this thing

in the realm of metals and minerals many do not like that

yet no! it is a mineral.

This ore, full of metals, does not belong among the seven;

for it is their mother of them all.

It has a gray coat and a green-red lining.

But understand me rightly, otherwise you will come to grief

and Nature itself can help you no further.

Mark: our ore is base, and yet very highly to be valued;

Saturn bears it within himself, and can exalt you greatly.

It floats in the air; even a blind man knows it well,

though one who sees may not recognize it.

The poorest peasant has it in house and yard;

the servant throws it out at the door so do the maid, the boy.

That does not make them know it: it is a woman’s work,

a child’s play, and the strongest of all strength.

If I were to name it more plainly for you, as peasants are wont to,

then you would have to confess outright before all the world

that it would be a lie that so small a thing

could be so full of powers and bring golden fruits.

Therefore the wise man keeps this wholly silent with all diligence,

with which the alchemist often is wont to deceive himself,

and thinks: “There is no ore except in the cleft of the mountains!”

No! our ore floats in the light air.

All that is in the world is fashioned out of it;

the elements themselves gather in heaps within it;

yet it is no element not earth, air, water, fire

and yet it is also all of them: a dreadful monster.

Guard yourself from frost and snow, from dew, from northern rain;

in thunder-water there is truly also poorer blessing.

It serves not for the work: urine, salt, eggs, blood,

nor what is reckoned as the fundamental “blood” of the great fire.

In sum, whatever only comes from those three realms

does not serve our art; it must withdraw.

Even the sun’s brightness must give way, for this “little thing”

was before the world therefore hear what I sing.

It is a noble thing of high worth and being,

and yet nonetheless base, that God may choose it.

It is still found daily; the wind carries it in its belly.

It is mere vapor and uncommon smoke;

the water that encloses it yet you can, in the earth,

When you strive very hard, to become well partaker of it,

Its point lies somewhat deep; if you seek it diligently, early,

Then you will find it in the hole with no very great toil;

There it creeps out and in, and often lets itself be seen,

By those who know it well indeed, and understand it.

Now it appears sphere-round, now oblong, now four-cornered;

A star-white sheen adorns the black crude matter.

In this you find the elements gathered together;

From this all things arise, even the metals:

Gold, silver, tin and lead, quicksilver,

Copper, steel,

Antimony and marcasite, and ores without number.

You yourself cannot live one hour without this thing,

Since it sustains you, and must give you strength.

You see it and do not know it; do you know it? I have named it.

Now I tell it: it is a salt a salt that no one knows,

Knows not what “salt” looks like. Now I give it to you to read:

It is the compressed being of the first Nothing;

A smoke from the Ruach, and thick star-sap,

Which gives the whole world its true nourishment-power.

It is called a Hyls, and Chaos is its name

A watery fire, the seed of fiery water;

From this alone the Stone of the Wise is “cooked,”

Which otherwise Nature by itself has never been able to do.

For this time I may not tell you anything clearer about it;

One might accuse me before God of grievous wrongdoing.

God gives it Himself to whom He grants it, and whoever loves it from the heart,

Will be comforted in his toil, and never be sorrowful.

If you say, “I do not believe it” well, I will not quarrel about it;

Yet the Art remains truly true, even though by evil people

It is contradicted to me; a wise man does not do that,

Even if simple Unreason judges me as unreasonable.

No greater folly is there than to revile such things

Which one does not understand yet the truth must stand,

Even though raging censure lays its claws upon it

And says it cannot be, according to its vain delusion.

Therefore, if you do not rightly know it, then only stop your railing;

Otherwise one truly sees a wretched ear (that cannot hear).

No wise man has ever despised the work of Wisdom.

What folly builds is wisely laughed at;

Therefore I do not write for fools and for mockers,

Who cry out of themselves: We know the true

Gods in this science! You fool, it is not for you,

For you only burn yourself at this bright

Light.

One thing more must I yet, my dear brother,

Write before you:

How one should pursue the work of the Wise with right profit.

The after-work is poor; the fore-work, Hard.

A clever man has to do this: that he swim through The sea.

Seek first the single EIV, the origin of all Things,

So that at the beginning it may not also, as it did with me, miscarry for you.

When you have then this thing, so separate from it:

Only the impure part; cast the pure into the grave.

After it has lain its time in the grave,

So bring it forth from the breast (guard this

Blessing In it lies the treasure) up into the starry Field.

See that it return again to our little world;

Otherwise the toil would be in vain. Now set about separating

The spirit from body and soul; you may well avoid starving

The great coal-fire, until Soul, Spirit and Body

By Art be separated; then give the Man his Wife.

He will hold her fast, she will clasp him heartily,

Each one here stills his burning desire,

And they are again with black cloth co-ver’d,

Whereunder most surely the White and the Red lie hid.

Here work cleanly, and hasten yet with leisure

That the white Bride may share the pearl-ornament.

For if thou trifle it away, then is the Treasure lost,

Which the King himself hath chosen for his Treasure.

Hast thou the pearl-crown, then will the King come,

Clad in purple; and (as I have heard)

Reward thy toil well unto thee, thou hast it good;

Keep this Treasure, as dear to thee as body and blood.

Behold, thus shall he in this world be blessed by GOD,

Who meets Him at all times with pure love;

Pure fear of God attains such a reward;

The fear of God alone crowns a virtuousson.

Therefore, whosoever once intends the Ground of Wisdom to find,

Let him fear and love GOD; let him beware of sins;

The mockers, slanderers, the liars, and the man

That holds too highly of himself here they are cast out.

Away with lying, hypocrisy; away, slanderous tongue,

mocking and derision; away, all devilish rabble!

You boast indeed of Art alas, but all your Art

is only jangling words, a blue mist’s empty breath.

But you who love God and your neighbour,

you are they to whom God gives true Wisdom;

the others are yet blind, and grope about for the door

that leadeth unto damnation. Who can, let him sing

with me:

In God I am content; I laugh at foemen’s raging;

to me it is all one, whether they blame or praise,

for my soul resteth in the true ground of Wisdom.

Lord, open in mine enemy eye and ear, heart and mouth,

that he may rightly know himself and Thee in the depth,

and not so unadvisedly run down to deepest Hell.

My God! ah hear me convert my enemy!

Give him the crown of Wisdom, who in Christian wise

is minded with me!

Conversation

Between Saturn, of the Wise, and a Chymist, concerning the true Materia of the Philosophers’ Stone and its preparatory work.

Saturn.

I am the worst thing, and yet likewise the best;

Therefore to me there come many wondrous guests;

And they seek little honey, yet stand there stiff and stark,

And are vexed only at my black beard.

Chymist.

What sayest thou? Shouldst thou have aught of good in thee?

I see as clear as the sun, that thy gifts are but mean:

Thou art lame, dumb, and deaf; black-grey is thy skin;

Thy body is full of stench, if one look on thee aright.

Who would, in such a case, put trust in thee?

Thou art full of knavery, and hast right sharp claws;

Thou art half a poison for honey thou givest gall;

How many a pious man hast thou brought to his fall!

Saturnus.

Why dost thou still so much snarl and foam? I can but laugh,

That thou pull’st down thy cap, and gap’st with open chaff;

I swallow what I get then off thou runn’st anon,

And fearest my wrath; so still the crown is mine alone.

Thou fool, know’st thou not this: that nowhere men so mutter

As in the darkness, in the shadow, and in the utter

Dun gloom? Though I be fairly black, yet am I then

Still comely: ’tis but thou that canst not see me well.

Go to my mine, and ask my workmen (all my knaves),

Whether they long not eagerly for my veins and caves.

They hold me in great worth when once they light on me,

And boldly call me still their honest “Biedermann” (true).

Such am I too; and is my blackness dear to me

As dear perchance to thee thy timid hare-heart’s glee:

That comes because thou know’st me not, nor yet my little brood,

That are black, green, blue, white, and red in shine and good.

The best I tell thee not. Yet if thou wouldst it learn,

Then must thou fix on one thing, and earnestly discern;

And see how thou may’st compass it bring that same thing to me,

And I will show thee then how thou may’st hit the door aright.

Chymist.

Ah, get behind me! many a time and often enough they have told me

Of thy one single “Thing”; and what troubles me most is this:

I truly do not know where that thing is to be found.

Is it a beast, an herb, a metal? come, tell me plainly.

Saturnus.

Just as though I were born for no end but this alone,

That I must tell it thee! yet sharpen well thine ears,

And heed with diligence what I am minded to say.

Where thou canst not see, there use thy spectacles.

In one word: I am a very child-devourer;

I swallow them as they are; the evil I make better,

Though I too do corrupt yet no harm comes of it,

So only it be carefully ordered after my will.

Chymist.

What drives thee then to it, that with such eager zeal

Thou lustest after children’s blood? one sees it by thy foam,

That clings unto thy beard, what manner of one thou art:

One that brings little profit, and only eats the best.

Saturnus.

Thou poor gulper, thou thou dost indeed like roast meat to chew,

And yet, when one would advise you to the game-meat,

You seize the raw (thing), and stake it down without toil;

The flesh you throw aside, and take your pleasure in the broth.

That is because you greatly fear you might burn yourself.

Chymist.

Ah, if only once I could truly recognize the game,

How would I, without delay, lay hands upon it!

In the hope that I too might once attain rest.

Saturnus.

I have told you already, that I am that which you seek,

Truly I myself am it; yet you defy (me) and build

upon your own opinion, and vex yourself over a thing

Which I alone possess and set before your eyes.

You know well that I am it, and yet you will not come to me.

The Wise bear witness enough of me, as of a pious

and true honest man do you then not understand

what Valtin says back and forth in his books?

Chymist.

Quite right! Valentin has written subtle stuff,

That leads one into ruin; he has driven me about

From one thing to another; he speaks of vitriol,

He lifts antimony up even to the pole;

And what is more, he sets it straight upon a wagon.

Saturnus.

Hear! let me too say a word on this matter:

Do not say BASILIUS say only SATURN;

He puts into thy hand as much as ever he can:

A shining mineral take it from his hands;

And if thou knowest how to turn this over rightly, with art,

Then the vitriol of which he told thee

Will soon come to light.

Chymist.

That is what troubles me:

He writes of vitriol, yet rejects the common kind.

Saturn.

BASILIUS is right he speaks of his own.

Chymist.

If it is not the common kind, then whence dost thou take it?

Saturn.

If thou wouldst have a share in it, then first stab the bear.

Chymist.

Now I am as clever as I was before.

Saturnus.

That comes of this: you have never yet read the writing rightly,

And think yourself to be a master yet you look only upward,

And do not heed, with understanding, your teacher’s meaning.

Chymist.

I am held in so little esteem in your eyes;

I say what I will, yet before you it will not pass for anything.

Saturnus.

Still less do I count for anything in your eyes;

I know you value me even less than that.

So wretched I appear to you and yet you would be called

A well-tried man, a son of the ancient wise.

“Yes behind him it stinks!” Though I have told you plainly

That I myself am the Thing have you even dared

To touch me? I stink before your nose

When I let my breath go, and am wont to blow winds;

Then you run away this by no means does

He who truly knows me, and has bound himself to me.

Chymist.

I see that perhaps there is still something in thee;

Tell me what art thou called?

Saturnus.

How art thou so bold,

That thou darest ask what my name may be?

Thou askest overmuch, and art full of hypocrisy.

Hear then, in one word: SATURNUS is my name.

I am servant and king as well; in me lieth all seed

For beasts, herbs, ore wilt thou yet have more?

Chymist.

That have I long thought; it would bring thee trouble

If one should question thee exactly: is not this a wonder,

That thou wouldst be a king, when all thy whole baggage

Is not worth a Dreyer for SATURNUS is lead!

Saturnus.

Bethink thyself well: we are indeed two

The one that I am, and the other that thou namest;

That other have I carried off if thou but knowest me

So now thou hast, in truth, heard enough this time.

Chymist.

With thy devilries thou hast quite bewitched me.

Are there then two Saturns? I read but of one:

That is the planet which, among the ore-stones,

Possesseth soft lead yea, as is well enough known;

So is black lead oft named SATURNUS.

But whence com’st thou?

Saturnus.

From Tribstrill out of the mill!

Where men set the pestles running, so that one may well feel it.

Art thou a master’s man, and know’st not even yet,

That two Saturns there be!

Chymist.

I hold it for a poem.

Saturnus.

There one sees clear as the sun that thou art not far advanced,

Nor hast perceived in our Art aught that savoureth of Truth.

Thou know’st not the names, and yet wouldst of the matter

Pronounce a judgement when thou art far too weak,

Yea, inexperienced.

Chymist.

To please thee, I will do it:

Yet at the last I must suppose, that besides Saturn

Among the metals there is yet another (find I it, or find I it not);

So will I henceforth leave this thing undecided.

Saturnus.

I well believe thee! Learn but to know the Sooty-Beard,

Who hath all things with him; then mayst thou call thyself

Right blessed in the world: to that I wish thee luck.

Look to it, and fail not, my son, in this point.

Chymist.

God help! if I could but attain unto this Thing,

Which is but One only, as now I have heard;

Yet it goeth hard into me, because there are so many

Names wherewith this wondrous Child is christened.

Saturnus.

Let not, dear friend, the names trouble thee:

Else wilt thou verily entangle thyself in nothing but error.

The name bringeth thee very little profit:

Remember, it must be the last Root.

Therefore look about you diligently, what kind of essence this is,

By which the metals, in their growing, are rightly restored.

They call it Vitriol; let not yourself be led astray:

You know well the common sort, of which the rabble speaks.

Ours, and ours alone, is the Mother of the metals;

Ofttimes it is very tender, like fine butter.

The miners know it well ask further there;

I know thou shalt at last perceive this matter.

Chymist.

Thou art a pious guest, and givest me good words;

Thou sayest freely, of what kind and sort

That essence is, from which the Stone of the Wise

Takes its true beginning should it then be gold-ore?

Saturnus.

Is then golden ore the root of the metals?

My son, bethink thyself hath it already slipped from thee

What I have told thee? Gold, silver, ore serve not,

Because this Work is ordered only from their PRIMUM ENS;

There hast thou it plainly enough in German.

Chymist.

If then it be the first essence

Of all metals, as I have often read,

Where then do I find the thing? tell me, what doth it look like?

Saturnus.

Thou findest it with me, if thou but knowest my house.

Chymist.

Methinks I have oft seen thee and thy house:

Thy grey coat gives plainly to understand,

That thy dwelling is not over-clean;

There one finds quite unmoved Lead.

Saturnus.

Now thou sayest somewhat indeed yet I will wager on’t

Thou knowest not what thou sayest.

Chymist.

Is’t not the fat Letten (fat clay/loam)?

Saturnus.

There one may hear already whither thou settest thy mind;

Therefore it remaineth so: my house thou knowest not.

For I myself am the house, and my coat beareth witness to it,

(As thou thyself hast said;) and here, upon this cudgel/knittle,

Is fast bound the black Hound of Hell;

If thou know him, and me also, then shall my house be known unto thee,

Chymist.

Now I see that in my mind I have been rightly deceived.

Saturnus.

Yes truly, now thou art deceived and lied unto;

I and my house are black what wouldst thou now have more?

Chymist.

That I do not know thee, grieveth me full sore.

Saturnus.

All that availeth thee not, that thou wouldst lament;

Thou shouldst by day and night lie earnestly in wait on me,

To see where I may creep in and out,

That my black dog fall not upon thy leg.

Chymist.

I know not what I should say to this business.

Saturnus.

Right so: thou hast no ground, art moist in many questions;

Thou fanciest it, that thou hast known me

But when it cometh to the proof, thou art put to shame.

Chymist.

How then shall I proceed? Here the metals are of no use;

The ores count for nothing; the salts are wholly set aside;

Yes, the metallic realm has with thee no place

Does this treasure then lie in the work of herbs and animals?

Saturnus.

These likewise serve not, because they have attained

The final end of Nature: the urine of young boys

Is mere rag-work.

Chymist.

Not even the boys’ urine?

Saturnus.

Because mine is better.

Chymist.

Thou makest a fool of me outright.

Saturnus.

Let it not vex thee that I tell thee the truth,

And do not trouble thee in vain with false things;

For what thou must have, that I have and am only I,

And no one else besides; be not so strange.

Ask only after my house, for there lies buried

What ores, beasts, and herbs must needs have in power.

Saturnus.

In my heart I always bear his silver, iron, lead,

mercury, gold, copper, ornament this I say without fear.

For I alone am the mine of the metals;

I alone should please you and others well.

In me all is One, and One is also all;

I creep through everything, as smoke through a house.

Chymist.

Now it is done with me; I do not know how to help myself.

I must not bark back at you any further, SATURNUS;

In a word, I do not know the single One thing,

Unless you give me somewhat better light.

Saturnus.

I have often told you that I keep the treasure,

In my thin breast; and my grey hairs

Plainly testify that the metals’ salt,

Together with the sweet fat, lies hidden in me.

Read the ROSARUS; there you can hear

That I am called SATURNUS “from the pipes.”

If that is not clear enough for you, then take black

Silberglett (litharge);

For this is truly the bed of all metals.

Would you have something more?

Chymist.

What is clearer cannot hurt,

But as it pleases you the ARIADNE’S thread

Alas, I do not see that!

Saturnus.

So mark this ground,

Which, first of all, I will make known to you.

Mark! the deeply hidden seed of our science

Possesses a mineral (I named it to you before, by name),

In which lies the whole power of all metals.

I take nothing away are you still not content?

Then prove from this thing what is called Above, Below,

And let it stand: what is Above is like what is Below.

Chymist.

I marvel at your speech it is far too scant!

Saturnus.

My son, do not press me, else I shall part from you.

Chymist.

Forgive me, father, that I ask yet one word:

Metals are of no use, by all the Wise men’s saying;

Hey why then do you call it a mineral?

It comes, in that manner, into the number of the metals.

Saturnus.

I have spoken rightly; that will I prove to you:

With good reason it is to be called a mineral,

Although it be not in the number of the Minerals,

As thou, with others, art yet of that foolish opinion:

It is a Mineral; yet it lieth not in the earth,

Where men find metals: it must be sought

Where its metal otherwise groweth; it rooteth in the air,

And hath therein a very dark vault.

It looketh metallic, and yet springeth not from metals,

Which are its children; let not that displease thee:

For where this ore increaseth, there is for ever

No mineral seen; and that at my end!

For I myself am that Thing; therefore am I the over-seer

Of the mineral kingdom, and the preserver of the metals.

Every one is my child; and whatsoever is called metallic,

Sprouteth only from my sweet spirit.

If thou canst comprehend this, I may well grant it thee;

But if thou know it not, then wilt thou also not be able

To attain thy end; and believe assuredly,

Wisdom’s high good fortune is ever against thee.

Chymist.

I perceive thus much now, that I labour in vain;

Therefore I also obtain so very poor a booty.

I will think on it, and let all stand;

Perhaps I may yet get to see the hand-stone,

What have I now gained from it, that I have spent so many years

In ignorance, and now at last perceive:

That all my doing was in vain, the means are gone,

Instead of gold and precious stone, I have filth for profit.

Saturnus.

Softly! my dear son, the door still stands open to thee;

If up to this time thou hast not hit upon my riddle,

Then set thyself stoutly to it; I will faithfully

Stand by thee in thy sour toil and labour.

Look here: what lies here what thinkest thou of the stone?

Chymist.

It is a dark lump; shall I call for help,

And take for assistance VULCAN and his axe?

Saturnus.

O dear one, not so hasty there is still good time.

Thou must first consider this thing more thoroughly,

Before thou darest to slaughter the offering rightly.

Much depends upon it, that thou knowest the first ground (origin),

And yet thou hast not done enough in this matter.

Chymist.

Has it such difficulty? That I had not thought.

Saturnus.

After hard hail and storm, the sun shines again;

Therefore do not despair; rather consider thyself well,

And with prayer and diligence direct thy heart to the work.

Now speak freely out: what wilt thou do with it?

How wilt thou deal with these precious things?

What lies in the ore (the lump)?

Chymist.

Here rests a wise spirit,

And a red soul; the body is for the most part

Hidden in the earth.

Saturnus.

How dost thou separate the things?

Chymist.

By repeated purification I accomplish all things.

Saturnus.

How is that done?

Chymist.

Dissolving, distilling,

And gentle calcining must adorn my work.

Saturnus.

Here you have spoken rightly. So go set to work;

May the Highest grant you, for a rich reward,

The Wise Men’s precious stone. If anything more still is lacking,

Then ask without fear; I’ll tell you readily.

Chymist.

Now it is the Cock’s Egg the stuff I will search for

In the subtlest way; then I will also try

How I may rightly solve it, since this is the chief aim,

On which my welfare rests, though it should seem ever so wild.

The thing looks not so fair as black velvet;

How soft and tender it is now my heart, desirously, flames

To hasten toward the fire.

Saturnus.

My son, you do quite right;

Remain always the faithful servant of Wisdom.

Chymist.

That I had not thought that so clear a spring

Should lie hidden herein! O how heedlessly

Many go about the work! Here comes the White Spirit;

Yes, even the Green Lion shows me his red blood.

Shall I then, down in the ground of the earth, truly find the Dragon?

I doubt it not!

Saturnus.

Thou must kindle a fire,

And burn out this hard stone very carefully;

So shalt thou find the treasure in NEPTUNE’S house.

Chymist.

That will I diligently do, and burn it wholly snow-white.

Saturnus.

Thou wilt, without doubt, know NEPTUNE’S house?

Chymist.

I know it full well; I will now go to the work.

Saturnus.

In a short time thou shalt see the cold Dragon.

Chymist.

Now I have all three: the Eagle and the Dragon,

Together with the Lion’s blood what must I do further?

Saturnus.

Thou must purify each thing very well,

And separate the uncleanness in the best manner.

Chymist.

I will cleanse it seven times and more,

And hope the toil shall at the end repay well.

Saturn.

You do well if you can for on this everything depends.

See that the cold Dragon does not, in the end, deceive you.

Chymist.

Truly I must confess: this is no honey-licking.

A blind man, indeed, in need will hold fast to his staff;

if one leads him onward but here there is no one

who tells a man anything, nor lends help and hand.

Saturn.

It would not be good for you either if one told you everything.

Prayer and labour are required; whereas the faint-hearted man

brings nothing to pass therefore only set your hand to the work:

Through labour you make your path to Heaven.

Chymist.

Well then, I cleanse the spirit together with the blood.

How horribly the thing stinks! I am by no means at ease.

Ah, ah how little there is of the pure, and how much

is the impurity!

Saturn.

The pure serves for play.

Chymist.

I cannot marvel enough at the matter,

That the lees sink down to the bottom

The pure separates itself, and rises up to Heaven;

But what is impure cannot lift itself up.

Now I see well enough what “pure” and “impure” mean:

Prayer and labour show me the right ways and grips,

So that I have hit upon the cleansing as is fitting

Although I have stood long enough before the door.

Saturn.

See now you recognize how hard this business is.

Work with prayer, and keep a chaste way of life.

You still have enough to do; although the cleansing

Has happened ten times, it still needs improvement.

Chymist.

Here I must stand still, and do not know what counsel to take.

Saturn.

Ask among the wise; consider their deeds.

Think what is now to be done bethink yourself, my son;

If you then strike upon this door, you gain the treasure as reward.

Chymist.

Help, God! where shall I now direct my senses?

Saturn.

If you will bind yourself further to me with true fidelity,

Then I will indeed tell you more.

Chymist.

Yes I will have nothing else,

Except that I here promise you faithful duty.

Saturnus.

It is easy enough to make promises yet how stands it with keeping them?

Therefore consider well; do not deceive me, an old man,

As you have done much before, and still do daily.

I tell you the truth therefore set yourself now in order!

Take heed of my words: the Eagle and the Dragon

You must unite, and make one out of the two;

Otherwise you accomplish nothing: the Spirit is what does it now

The Body alone can do nothing; keep that well in mind.

Chymist.

That is a hard point, and a tightly-knotted knot.

Saturnus.

Only do not seek the living among the dead.

Chymist.

What counsel then is there for this?

Saturnus.

See how you stand now

Like butter in the sun.

Chymist.

If you do not go with me,

All my good fortune falls into the well of despair.

Saturnus.

My dear son, softly! I am not so minded.

I offer you my hand and counsel therefore do not despair,

For all is truth that my tongue speaks.

It is true: your spirit is pure, yet there still clings within it Much earth.

The greatest care is that it be separated,

Since it brings harm in our high Work;

But if that be taken away, then it is the strong Strength.

And this is the point at which so very many err

Yet, on the contrary, they entangle themselves with boldness,

And do not know with what one ought to separate

The earth from the spirit. I swear to you,

That nothing can do such a thing except the spirit’s companion.

That same companion leads many a master astray in this matter;

It loosens him from the earth, and itself too leaves Its house;

It becomes, with the spirit, a spirit then something noble comes of it.

Do you understand what I say?

Chymist.

Now I am out of the dream:

The spirit and his companion are indeed of one tree.

Saturnus.

Unite them, as I have told you,

For so you complete the first hare-hunt.

Pay very close heed to the weight.

Chymist.

Does it matter here?

Saturnus.

If thou best aware of this, the blessing is assured thee,

Whereby the Fire of the Wise becometh known unto thee;

Else shalt thou bring the Work unto no firm and settled state.

Chymist.

I thought I had the Fish already in my hands;

Yet now I know not whither I should turn me.

MERCURIUS is pure; pure is the noble Body;

These must become One, even as are Man and Wife.

Now it dependeth on the Weight, and on the Fire of the Wise

O wondrous Work! the Nut is hard to crack.

Saturnus.

Twofold is our Fire: the one is called Light,

And warmeth outwardly, according as the inward is directed.

Beware of strange (foreign) heat!

Chymist.

How standeth it with the Weight?

Saturnus.

What RIPLEUS telleth thee, thereby set thyself aright, soundly!

Like unto like, rather content thyself therewith;

If thou hit my Nails rightly, it shall rejoice me.

Forget not the Mediator!

Chymist.

What new thing do I now hear?

Chymist.

What “mediator” do you mean? Why do you make such a great outcry

in this difficult Work? I thought all was well,

if Eagle and Dragon are there, together with the Lion’s blood.

Saturnus.

If the mediator is lacking for you, you will accomplish nothing;

for this one alone is he who must settle all strife;

otherwise the old Dragon thrusts the Eagle far away from himself,

and will not accept him at all believe that for certain.

Chymist.

Yet the Wise write nothing at all of this business;

BASILIUS speaks of a purple mantle

might it perhaps be this?

Saturnus.

No, this is not it!

Nor is it any foreign thing that directs this Work.

Whoever wishes to bring Fire and Water into one,

must skilfully lift up their unceasing conflict,

since neither loves the other: whoever knows their mediator,

can easily make from them a strongly-burning ice.

So too in our Work! You have in your hands

What you need if you know how to apply it rightly;

Then you can surely, in a short time,

Attain without toil what brings you worldly joy.

With this, take your leave, so dear (to me). Think often on the words

Which Valentin says to you in another place:

Consider well the beginning and its final end;

Take heed of the middle I depart now, going.

Chymist.

How exceedingly hidden this Work is,

And how wondrously covered with flowery speech;

Therefore I will strive if I soon find the Mediator

May God’s glory fill field and forest.

Riddle

Seek the center in its earth,

From which metals are bored (drawn forth).

In a sphere you will find

What you intend to fathom.

Take from it the vapor of its spirit

That is the key to the Art.

Go on until everything turns reddish:

That is the wax that withstands the fire,

A precious oil and great treasure.

In me you will find the place for it,

Where fire, earth, air, and water lie;

Let none among them deceive you.

Shut the fire into the power of water

In this thing life laughs.

Therein is the true bride of life,

Whom many take for a mere maid.

Clothe her with red gold,

So will she truly become gracious to you!

He who can our red blood

The Eagle’s silver-glow

Together with the sweet fat

And the salt full of fire,

Fitly compound together

And moistly bathe,

Until out of the fire’s glow

There grows fiery flesh and blood

Him may one count blessed.

SOLI DEO GLORIA.

To God alone be the glory.