Artephius - THE KEY OF GREATER WISDOM.

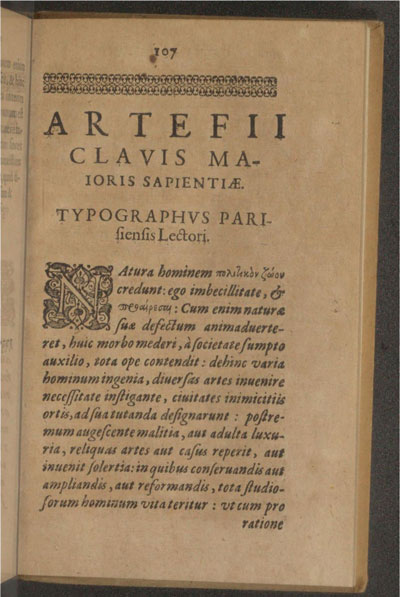

ARTEFII CLAVIS MAIORIS SAPIENTIAE.

The Parisian Printer to the Reader

They say that man is by nature a politikon zoon (a political animal); I believe it is rather by weakness and deficiency. For when man became aware of his own natural limitations, he sought to remedy this condition by means of society, striving with all effort to seek help from others. Thus, the diverse talents of men, urged by necessity, invented various arts; cities, arising from mutual enmity, designed institutions for their own defense; and in the end, as malice grew or luxury matured, the remaining arts were either discovered by chance or found by human ingenuity. In maintaining, expanding, or reforming these, the entire life of human study is consumed, since desires differ according to each person's goal, and the will, being obscure, often presents falsity as truth.

Many have thus turned to mataiotechnia (vain arts) because they did not properly understand the end of architektonike (the master art), and have fled to subordinate ones. As the suitors of Penelope, unable to possess the lady herself, turned instead to her maidservants, so too those whose intellect was not blessed enough by nature to see the truth with their eyes—or, having seen it, were disappointed in their hope of attaining it—have clutched at what was within reach, perhaps not wisely.

For the difficulty of a work should not deter those who still possess some greatness of spirit from attempting it. Many arts have been discovered both for the sake of others and for private benefit, and those which benefit the commonwealth most ought to be pursued with the greatest diligence. Chief among them is the one devoted to alleviating the sufferings of human nature caused by poverty and disease, which is even called a hieran technin (sacred art).

In this art, the men of earlier ages, having discovered something, committed it to writing—hence so many excellent volumes of this discipline have survived even to our own times.

Following their example, I have done what I could to benefit all, if not by composing, at least by publishing works that were still wanted. However, as there is difficulty in every endeavor, which cannot be overcome without effort, so in this art what is most essential is often most sought after. But how to obtain it—Johannes Pontanus, in a brief letter he wrote on this art, referred the reader to Artefius.

When I noticed this and obtained a copy of the work, I did not wish to deprive you of its light. For Heliodorus taught us, in his treatise to Heraclius on the art, that the spirit of wisdom is:

"Not to envy those who wish to learn." (Mēden phthonountes tois theloisin manthanein)

Thus, virtue and those things worthy of a noble name rejoice in being propagated, and goodness is believed to be diffusive of itself. We cast out those who think wisdom should be kept to themselves.

As for who this Artefius was, it is not entirely certain. Some believe he was a Jew. Something about him can be found in Roger Bacon and Cardan. His level of learning this book may demonstrate—though if there are things that seem beyond belief, consider them riddles, I ask you to believe; while those that are plainly physical are composed with marvelous skill.

And in this, indeed, the most difficult thing of the master art is made clear with an easy demonstration:

"Unless the combination of bodies is well made, all effort is vain and void."

Truly, many other things are explained in this book, which could not be perfected or understood without the greatest labor.

So, reader, accept this favorably and justly—and above all, embrace it. If something of better quality should come to us later, you too shall share in it.

In the year 1609.

Farewell.

ARTEFIUS

THE BOOK BEGINS

Which is called the KEY OF GREATER WISDOM

This book is divided into three chapters, and none of them is complete without the others.

The first depends on the second and third; the second on the first and third; and the third on the first and second.

The first deals with the composition of the elements, both higher and lower, and with the natures, equal and unequal, and their conversion into each other, and their generation.

The second concerns the generation of mineral bodies, both natural and artificial.

The third deals with the generation of plants and animals, and with the binding of body with spirit—and also of the soul, and of one animal with another.

Let us therefore praise God, who is the observer of all things, and from whom nothing is hidden. He is bound to His creatures through His Word, and yet separate from them inasmuch as He transcends them. I do not believe that He created anything equal or like unto Himself. Among His greatest benefits is that He bound our body to the subtlest of all the elements, namely the soul, which clearly perceives hidden things—provided that the bodily powers do not dominate it. For the stronger the powers of the body become, the more the soul’s virtues are weakened; and the more the body is altered, the more subtle becomes the soul’s insight.

Therefore our master Belenius the Philosopher said:

"Place your light in a clear glass vessel."

And note that all the wisdom of this world revolves around these three things:

The binding of the corporeal soul to the corporeal soul,

The spiritual soul to the corporeal soul,

The spiritual to the spiritual.

But the binding of the corporeal soul to the corporeal is closer and easier than that of the spiritual to the spiritual.

Concerning this third, the ancient wise men wished to write little. For they said that no one could attain knowledge of it unless his nature were divine and spiritual—and his birth as well.

Later, all the ancient sages in agreement said without disagreement:

"That which is above is like to that which is below"—and vice versa.

And every subtle thing comes from the gross, and the gross from the subtle.

And the entire composition of the world—be it greater, middle, or lesser—is one single composition.

Know also that every binding of worldly things is like the binding of number, that is: from units, tens, hundreds, and thousands. For from the fingers one counts the first group, saying one, two, three, four—these added together make ten; similarly, ten, twenty, thirty, forty, added together, produce a hundred; and so on with hundreds and thousands.

Since number is nothing other than the binding of one thing to another, it is clear that the unit itself has no nature. But when we take the number two—the first number—and divide it equally, each part is a unit. If we add a unit to two, we get three; double two and we get four; add a unit to four, and we get five; add three and we get seven; add one and we get eight; add another unit and we get nine; finally, add two and we get ten. The same pattern holds for hundreds arising from tens, and thousands from hundreds.

One day, my master Belenius the Philosopher called me and said:

"Come, my son, I hope that you are a man of spiritual understanding and that you can attain the highest degree of wisdom.

Therefore, I shall ask you a question, and you shall answer me."

And I said to him:

"Indeed, merciful father and honorable master, ask your disciple and I will answer you as best I can."

And he said:

"Into how many kinds is Nature divided?"

And I said:

"Into four."

And he said:

"What are those four?"

And I said:

"Simple, simple from the simple, compound from the simple, and compound from the compound."

And he said:

"Which of these is the first?"

And I said:

"The simple."

And he said:

"And what is that simple?"

And I said:

"Two natures, as much as one is active, the other is passive."

And he said:

"What are those two natures?"

And I said:

"The first of them is the nature of heat, and the second, of coldness. The nature of heat is active; of coldness, passive."

And he said:

"What comes after the simple?"

And I said:

"The simple from the simple."

And he said:

"What is that?"

And I said:

"The nature of heat and the nature of moisture, and the nature of coldness, and the nature of dryness."

And he said:

"How are those two natures generated?"

And I said:

"The Creator of all things in the beginning, without the utterance of a word, said: ‘Let such a creature be’; and afterward the first nature, or the prime matter, was created by God. This is that which Aristotle in the first book of Physics and Plato in the Timaeus likewise wrote about, which is the first passive, or receptive thing; which could not be great nor small, nor subtle nor gross, nor moving nor at rest, nor can it rightly be defined by any other name, nor likened to any other thing: in which indeed all things existed primarily, that is, in potency, which is the medium between actual being and non-being.

And so that it might be brought into act, He created a second creature, namely, the efficient cause—similar, that is, to the celestial sphere, which He decreed to call light.

This light enclosed the first created sphere within its concavity.

And of this nature and first creature, another creature arose, of heat and motion; whence it is clear that another first was of coldness and dryness: and because those natures were close to one another, heat struck coldness, and coldness compressed itself by condensing. And because it is the nature of heat and of every subtle thing to penetrate, heat penetrated even to the center of coldness: and since the end of every thing is its contrary, and to its motion both motion and rest are opposed,

Therefore the motion that was toward the center or the middle ceased, and another motion succeeded in the middle: for one part of heat tempered itself with an equal part of coldness, and from that tempering came the nature of moisture. And because its nature was intermediate between the nature of heat and of coldness, therefore it obtained a middle place between the two, and that motion was from the center to the middle, to which succeeded another motion, namely from the summit to the middle, and from the middle to the middle between the lowest and the highest, and again from the lowest to the middle—that is, from the middle to the middle between the middle and the lowest.

For one part of heat tempered itself with an equal part of moisture, and from this tempering came the nature of heat and moisture, whose place, as we have said, was between the place of heat and moisture. And because, as we said above, the nature of moisture is composed of one part of heat and one of moisture or coldness equal to it, it follows that the nature of heat and moisture is one part coldness and three parts heat. In the same way, the nature of coldness and moisture is aggregated from the nature of coldness and the nature of moisture equally."

And because the nature of moisture is half of heat and half of cold, it follows that the nature of cold and moisture is three-fourths cold and one-fourth heat.

Now therefore we have the second sphere of the first nature of the four spheres mentioned above: the first of which is cold and moisture, which the ancient sages called the sphere of spirit; above this is the nature of equilibrium, which they named the sphere of the soul; afterward, the nature of heat and moisture, which they called the third sphere; and finally, the nature of heat and dryness, which they called the fourth sphere, and here it is fixed. And because, as I said before, when those two first natures were mixed together, there was no motion from above to below or vice versa, but all the spheres moved in a circular motion.

Now we said before that the extreme of every thing is contrary to itself, and that not only is the motion from below to above opposed to the motion from above to below, but also to rest; therefore we said that a part of heat which had not mixed with the nature of cold for the generation of moisture remained below, mingled with cold; and because there is no vacuum in nature, in place of that heat which had descended, a certain part of cold equal to it moved in.

Now therefore it is clear that these spheres were interconnected. The lowest was the sphere of cold and dryness, in which there is no heat; after it follows the sphere of cold and moisture, with three parts cold and one heat; afterward, the sphere of equilibrium, which is the sphere of the soul, whose half is from the nature of heat and the other half from the nature of moisture.

Now we said that the sphere of moisture is half from the nature of heat and one-fourth from the nature of cold. The uppermost sphere after this is from the nature of heat and dryness, and in it there is nothing of cold. Thus you see how these spheres are ordered in relation to one another.

And he said: Now you have sufficiently demonstrated to me the natures of heat and cold; but what is dryness, which you have not yet explained?

And I said: Dryness is simply the privation of moisture; for in that which has no moisture, we call it dry.

And he said: Now you have sufficiently explained to me what is simple, and what is simple from the simple.

Now therefore tell me, what comes after that?

And I said: The compound from the simple. And he said: What is that?

And I said: The four elements, which are fire, air, water, and earth. And he said: How are those four elements generated? And I said: The nature of fire, namely heat and dryness, tempered itself with the nature of heat and moisture, and from this equal tempering came the element of fire; and the element of fire tempered itself with the nature of moisture, and from this tempering came the element of air; and the element of air tempered itself with the nature of cold and moisture, and from this tempering came the element of water; and the element of water tempered itself with the nature of cold and dryness, and from this tempering came the element of earth.

Therefore fire is subtle air, hot and dry; air is thick fire, hot and moist; water is thick air, cold and moist; and air is subtle water, hot and moist; and water is subtle earth, cold and moist; earth is thick water, cold and dry.

And he said: What is that which is composed of the simple?

And I said: The compound of the compound?

And he said: What is that? And I said: It is the body of the corporeal soul, which is from the animal body, and the body of the corporeal spirit.

And he said: What is the spirit of the animal body, and how are these bodies generated from the elements?

And I said: The element of fire tempered itself with the element of air, and from this equal tempering came the body of the corporeal soul; and the element of water tempered itself with the corporeal soul, and from this tempering came the body of the corporeal spirit; and the body of the corporeal spirit tempered itself with the element of earth, and from this tempering came the corporeal body.

Afterward, water mingled with this corporeal body and tempered itself with its more subtle part, and from this tempering came the body of the spiritual body; and air tempered itself with the more subtle part of this spiritual body, and from this tempering came the animal body; and fire tempered itself with this animal body and mingled with its more subtle part, and from this tempering came the body of the corporeal soul. And this is what the ancient sages sought; and it is from this tempering, when it is tempered with an equal tempering of water, that the body of the spirit of the equal body is generated, as we said above; from which, when tempered with an equal part of earth, the equal body is generated, which is the Sun. And if it were not for the diverse actions and influences of the celestial bodies upon the lower bodies, all mineral bodies would be gold.

For all things are from the same origin, and their souls and spirits are from one thing, and they differ only according to more and less, and according to the diversity of greater or lesser decoction.

Therefore, their diversity arises from the diversity of the influences of the celestial bodies on these lower things, just as their number corresponds to the number of the seven planets. From nature come their colors, odors, tastes, and other accidents.

For lead, from the part of Saturn, its nature is according to its nature.

Tin is from the part of Jupiter, its nature according to its nature.

Iron is from the part of Mars, its nature according to its nature.

Gold is from the part of the Sun, its nature according to its nature.

Quicksilver is from the part of Mercury, its nature according to its nature.

Silver is from the part of the Moon, its nature is according to its nature.

Copper is from the part of Venus, its nature according to its nature.

Afterward, these mineral metals are changed into each other and altered just like the elements from which they consist.

For fire becomes air, and air becomes fire; likewise, air becomes water, and water becomes air; water becomes earth, and earth becomes water, and so with the others.

And know that everything composed of elements has within it the four natures, namely: heat, cold, moisture, and dryness.

And if someone says that something is composed of only two of these four natures, we shall say: then it is composed only of cold and dryness; and because that compound is cold and dry like earth, its nature will be of the nature of earth, its touch and odor like earth.

And if someone says: but earth is cold and dry in the fourth degree, and that compound is not in the fourth degree?

We say: since they are both of the same complexion and differ only in degree — that is, one is in the fourth degree and the other in the first, second, or third — it is not impossible for the one in the first, second, or third degree to reach the fourth, unless it be due to the admixture of a contrary quality. Therefore, it was not mixed from only two, but from three, against which a contrary was set.

And you should know that every mineral is subtle earthiness, and a plant is a subtle mineral, and the animal body is the subtle part of the plant.

And from the elements are generated mineral bodies, and from the minerals are generated plants, and from the plants, animals. And because everything is resolved into that from which it is composed, therefore animals, when they are resolved, generate plants from themselves by way of resolution; in the same manner, from plants come minerals; and minerals from elements. And elements must necessarily be resolved into their natures.

And he said: Tell me, what is dense, and what is subtle or delicate?

And I said: The dense is body; the subtle, however, is spirit, and the subtle spirit of the animal is nature.

And he said: What is body?

And I said: A body is that which has something apparent and something hidden. That which is apparent is its grossness and density; but that which is hidden is its subtle part, namely the spirit and the soul.

Now the body is composed of soul, spirit, and corporeal matter; but once the body is corrupted, then what was called spirit is afterward called body, and what was called soul is afterward called spirit. Therefore, the greatest thing is that the spirit is the subtle part of the body, and the soul is the subtle part of the spirit. All of these, as we said above, are generated from one another through the path of composition or resolution, and are separated and altered in turn, just as we previously said about the elements themselves.

But this does not happen unless one nature enters into another — for example, when we want something to be cold and dry in the fourth degree, and we intend to change from the fourth degree of coldness and dryness to the same coldness and moisture, we will change it first from the fourth degree of coldness and dryness to the third degree of the same, then to the second, then to the first, and then to the mean between them; then to the first degree of change toward moisture, then to the second, then the third, and finally to the fourth degree of coldness and moisture. And if again we want to change it to the fourth degree of heat and moisture, we will change it first to the degree of coldness, then the second, then the third, then to the degree of equality in cold and moist; then to the first degree of change on the side of heat, then to the second, then third, then to the fourth, until it becomes hot and moist in the fourth degree.

And if again we wish to bring it to the same degree of heat and dryness, we shall bring it back to the second, then to the first, and finally to the degree of equality in heat and moisture; then to the first degree of dryness, then to the second, then to the third, then to the fourth. Thus, we will have changed it from the fourth degree of coldness — and their diversity is according to the diversity of the celestial bodies corresponding to them, from nature, and always according to the likeness of odors and flavors.

Let us say, therefore, that at the beginning of creation each of the planets was in direct conjunction with its own sign in the zodiacal sphere, and thus they acted, and their operations descended to the earth, until mineral bodies were generated proportional to them. And afterwards these celestial bodies moved: hence the connection and relation of lower things. And the minerals previously generated were corrupted, and then the aspect of the celestial bodies in relation to the lower things returned again, and plants were generated from the same matter which was previously under the form of mineral bodies. And finally this motion ceased, and the plants were corrupted, and the motion returned a third time, and from these plants animals were generated.

We have therefore said that the nature of mineral bodies is like the nature of the earth: cold and dry. The nature of plants is of the nature of water: cold and moist. The nature of animals is like the nature of air: hot and moist.

And if anyone objects and says: how can you say that the nature of minerals is cold and dry, and that of plants cold and moist, when we see that many minerals kill animals by their heat?

To this we respond: if a mineral is found which kills an animal through its heat, it is because the planet from which that mineral comes exerted much stronger operations, and likewise everything that came from that planet exceeded the planet itself. Therefore, if something is tempered by a planet from which it originated, we say that in its operation it is cold; and if again the planet and the animal are tempered in comparison to it, it will be found cold and moist.

CHAPTER 2.

On the Generation of Minerals

Let us now speak of the generation of minerals. Some have said that the nature of all minerals is quicksilver (argentum vivum) combined with sulfur; and others have said that the root of those minerals is quicksilver with sulfur.

Let us therefore prepare the root until we reach the branches. And the reason for this opinion is that they considered only the surface-level nature of mineral bodies. For if they had governed themselves by the deeper secrets of nature, they would never have fallen into such opinions.

We say, therefore, that even if we grant that quicksilver and sulfur are the primary natural constituents of mineral bodies before their congelation (solidification), yet after the congelation of quicksilver and sulfur, it is impossible to generate mineral bodies from them. For the agent that causes congelation has already altered them into its own nature.

A clear example of this is the composition of soap: if one takes water extracted from ashes and oil with certain other substances and cooks them in a certain way, soap is generated from them. But if one were to take each ingredient separately and cook it until it congealed, and then try to make soap from them afterward, it would be impossible.

Now sulfur in its first state was a water whose nature was cold and moist. Later it was converted into air, whose nature is warm and moist; and afterward into fire, whose nature is warm and dry. Later again, water tempered itself with that fire, and from this resulted a composition of male and female.

So, we say that although the nature or root of minerals may be quicksilver and sulfur, we must not take them in their raw state—as that from which mineral bodies are made—but rather we should take that which is already derived from the mineral bodies. A clear example of this is found in plants.

We know that the generation of a plant is from water mixed with subtle earthy matter, as we said before. Yet if we were to take just water and earth, we would never generate a plant. Therefore, we do not take the raw materials from which a plant is made, but rather what comes from the plant, namely, the seed (like the egg of an animal). After we know that the egg is generated from subtle earth mixed with water, we return it to the earth until what was diminished is replenished.

And we also say that the generation of metals in the belly of the earth happens in the following way:

When the Sun acts upon the lower regions, it heats the earth with its warmth. A portion of that heat remains in the interior of the earth. When the Sun rises above the earth and finds that some heat is hidden within, then by natural necessity a similar heat must rise up together with the newly generated heat. If it meets with some water, it dissolves it and converts it into vapor.

This vapor rises upward until it encounters a proportionate heat. When the Sun descends toward the West, this proportionate heat decreases, and the vapor condenses and descends again by distillation.

Then, when the Sun rises again, and its heat again becomes effective, the same thing happens: the vapor rises, condenses, and distills again. Thus, this process of continual subtle refinement and distillation does not cease until all the oil contained in the water is dissolved and completely mixed with the water—until all is converted into oil.

Now, if this oil encounters any portion of sulfur and the two are mixed—and if the quantity of water is equal to or slightly greater than the quantity of sulfur (just enough to incorporate it)—then from this will be generated gold or silver, and so with other metals according to the degree of decoction (cooking).

If, however, the quantity of sulfur is greater than that of the water, a mineral body will be generated from them, but it will not belong to the class of the seven canonical metals (the "seven mines").

We have already said that in the artificial generation of mineral bodies, we do not seek the raw substances from which these bodies originally came, but rather that which proceeds from them, just as we illustrated earlier with plants. For we said that we take the "egg" of the plant and consider from what it is generated; and after knowing that it comes from subtle earthy matter mixed with water, we entrust it again to the earth—thus also with minerals, we take the egg of the mineral, and then investigate from whence it is generated. Once we know this, we also know from what it must be nourished.

We know that the thing from which this egg is generated is a mixture of fire and water.

We also said that nothing is generated without the union of male and female.

And when we prepare the substance with the preparation suitable to it, gold or silver is generated from it. You must understand, however, that this cannot happen without putrefaction and solution—just as in plants it does not occur otherwise. For fire does not act upon a thing unless moisture is present.

Therefore, the cause of fire’s entrance is heat and moisture. For nature does not bind to anything except to a nature close to itself. Thus, when the moisture of the solvent encounters the moisture of what is to be dissolved, the two are bound together. Yet we do not dissolve the entire composition at once, because if we did, we would destroy the egg entirely. Instead, we dissolve it part by part, until that which is contrary to the solvent's nature is separated from the dissolved substance.

You must also know that this is where the egg of the plant differs from the egg of the mineral. For the mineral egg cannot putrefy without being ground or triturated. The humidity of the solvent cannot enter it without such grinding, due to the adhesion of its parts to each other. In contrast, if we were to grind the egg of the plant, we would destroy the plant’s form, which lies within it potentially.

As we said earlier, although fire is the acting agent on bodies, air—or rather its heat and moisture—is the actual cause of entry. But because the moisture of air is contrary to dryness, the coldness of water is also needed to temper it. And since water cannot be fixed in fire without earth, earth is likewise necessary, to fix the water.

We have already often said that generation cannot happen without the conjunction of male and female.

Now, fire and air are masculine elements, while water and earth are feminine. Fire is male to water, and air is male to earth. However, fire cannot mingle directly with earth without a mediator, which is air—since air is related to fire by its heat, and close to water by its moisture.

We have said repeatedly that nature embraces only that which is similar to itself. Therefore, air, by its harmony and affinity with both fire and water, becomes a mediator between them in generation. Likewise, air is contrary to earth in both of its qualities—air is warm and moist, earth is cold and dry. But water, because of its coldness, agrees with earth, and because of its moisture, agrees with air. So water is also a mediator between air and earth, generating harmony.

It is therefore clear that fire and water cannot unite directly, but only with air mediating at one end, and earth mediating at the other. And this is the point we wished to explain.

Now that we have declared that the mineral egg is generated from fire and water, and that it must therefore be nourished by the same, and knowing that fire is male and water female, our task now is to seek this male until we find him.

Now then, we have already said above that mineral bodies are of the nature of earth, whose nature is coldness and dryness, and that the amount of fire within them is small—present only in potential, and less than the second degree. Since minerals are from the vegetable realm in actuality, their nature is found to be cold and moist; and because the nature of what is cold and moist is composed of three parts coldness and one part heat, and even that fourth part of heat is buried deeply within the three parts of dryness, it is therefore necessary to ascend to the third degree, which is the animal realm.

And because the nature of the animal, as we said earlier, is hot and moist, it is clear that it consists of three parts heat and one part moisture. But since the animal, when it is complete, is mixed and balanced—its coarse combined with its subtle—it does not move from below upward. So we take from the animal that which is not complete, and we entrust it to the cucurbite (flask) and alembic for distillation.

And first we distill water, whose whiteness is manifest, while its fire is hidden as redness. Then we distill air, whose manifest quality is yellowing, and its hidden quality is greenness. And finally fire remains in the earth itself.

We then apply upon it a stronger fire, mercilessly, until we draw out all the fire from the dead black earth, in which no life remains. Afterward, we preserve the water, that is, the air and the fire—each in its own vessel—until the time of conjunction. Then we take that earth, and we apply fire to it until it becomes white. And after this is done, we take equal parts of each of the elements, and we mix them together.

And because this water is equally composed of the four natures, we have no reason to fear in our operation—except to be secure against corruption. For it is tinged with its own fire, it enters into its own oil, it is preserved from burning in its own water, and it is fixed into its own earth. Water is bound to earth through its coldness; air to water through moisture; fire to air through heat.

For example: from the composition of Mars, which is hot and dry, with Jupiter, which is cold and moist, the Sun is generated.

But know that mixture is twofold: there is a total and a partial mixture. Partial mixture is when body is mixed with body, but spirits are not mingled together—as happens in the fusion of fusible bodies by fire alone.

But total mixture is when bodies are mixed with bodies and spirits with spirits, with proper temperament—and this does not occur without putrefaction.

Now let us show why the Ancient Wise have said that one part of this elixir can transform a thousand parts: for the secret lies in the fact that every subtle thing occupies seven times the space compared to the gross matter.

Thus, one part of heat converts the Moon into the Sun—and this is if it has been taken from the mineral realm. But if it is from the vegetable, one part converts six parts of the Moon into Sun. And if it is from the animal, one part converts thirty-six parts in the first degree of subtlety. If it be of the second degree, one part converts 138 parts; in the third, 228 parts; and if in the fourth and final degree, it converts a hundredfold of that again.

And this is what we wished to show.

We have now sufficiently determined the generation of metallic bodies, both naturally and artificially, and with this, we complete this chapter.

CHAPTER 3.

The third chapter begins, in which the generation of plants from minerals, and similarly the generation of animals from plants, is discussed, as well as the binding of the spirit of the plant with the plant itself, and also the binding of the soul with the animal.

After we spoke of equal and unequal natures, and of the elements, both superior and inferior, in the first chapter, and also of the generation of minerals in the second, we will now, as promised, speak in this third chapter about plants, animals, and their generation.

Therefore, let us say, as in the first chapter, that water tempered itself with earth, and from this tempering a stone was generated; then air tempered itself with water, and from that a terra (soil) was generated. Its manifest qualities are cold and dry; its hidden qualities, warm and moist. Afterwards, this earth tempered itself with water.

Now, as we have said often above, nature embraces nature that is nearest to itself: therefore, the moisture of water was bound to the moisture of air, and the coldness of water to the coldness of earth; but the moisture of air was bound to its own heat.

When the eastern Sun rose, and the heat of the air was joined to the heat of the Sun, it was necessary that the plant extend itself and grow. And because we have already said that the coldness of water was bound to the coldness of earth, parts of the earth—subtler parts—ascended with parts of the water, tempered themselves, and mixed with those parts of the water. From these, the egg of the plant was generated, in which indeed the plant existed in potentiality.

But after the egg reached the limit of its variation, its moisture—by which it was nourished—was hidden away, and it became hardened and dried out.

Therefore, since we know that the matter of this egg is a mixture of subtler parts of earth with parts of water, we also know that it must be nourished by them, until that which was in potentiality is brought into actuality and a plant is generated, whose flowers, fruits, and leaves are from it.

But this plant egg differs from the mineral egg in this: it does not need to be ground up (triturated) so that the moisture of putrefaction may enter its parts and mingle with its parts; for if we ground it, we would destroy the form of the plant existing potentially in it, and the leaves would turn into non-leaves.

Also, in the parts of the plant egg, there was not such compaction as to prevent the moisture of the subtle from mixing with the moisture of the dissolving body.

Thus it is clear that the substance of the plant consists of parts of water mixed with subtler parts of earth.

But we have said before that the plant is the subtle or delicate part of the mineral, and that it is generated from the tempering of water with the same (subtle earth). This, therefore, is the generation.

TO THE READER.

Theory gave practice to the ancients, and some work of admiration followed, and contemplation followed admiration: in the Didactics, however, the first part seems to prevail. Certainly, Artesius also imitated this order. For having described those things which were necessary for the knowledge of nature, now he proceeds to art. But since not only the fountain of virtue, but of all good things, the gods placed beforehand,

Therefore he enigmatically described this third chapter, and because the Jew moves the Magi with a comparison made about the demon, Reader, let the comparison move you: Thus long ago Stephanus to Heraclius said: about the making of gold by sublimation, whose explanation he gives with these words: “so that the matter is stripped, and naked it remains with only soul, and spirit, and subtle fire, and takes color, and becomes more fiery, and more retentive: just as when the body departs, as that of demons and those who come beneath.”

That the Author was familiar with such characters in the veiled sciences is also attested by Roger Bacchus, about the admirable power of art and nature.

Therefore do not despise the form of these, for perhaps they signify something, not all that is placed in figures ought to be thought to signify something: for many, on account of those which do signify, are joined for the sake of order and connection. The earth is cut only by the plowshare; with these things I wish you to be warned, that all written in this chapter is to be taken analogically, and that Artesius wrote about magic no less than about anything else, which perhaps we shall at times demonstrate in annotations.

ON THE GENERATION OF ANIMALS.

The generation of animals from plants is, as we have narrated, if God wills it, that when the plant decays in the womb of the animal, its subtle part is separated from the gross after its putrefaction; and since we have already said that the nature of the plant is cold and moist, and that it is generated from the tempering of water with subtle parts of earth.

Therefore, after putrefaction, the coarser parts of the earth are separated from the parts of the water; and since the nature of water is cold and moist, as we said before, one part of this coldness and moisture tempered itself with an equal part of heat and moisture in the animal itself, and from this tempering is generated the nature of the soul, which is the nature of equality: the remaining part ascends to the brain, from which is generated the nature of the sense; and since, as we said, three quarters were light and one quarter darkness, it is therefore clear that in the nature of sense, the nature of light dominates the darkness: that light is reflected from the part of darkness to the heart and illuminates it; and if it be an animal of erect stature, it does not have sense spread widely in the body as it is gathered, but is dispersed throughout the body: and this is the reason why other animals do not run about like man.

The composition of the human body, however, consists in a certain mixture of equal natures with unequal ones.

The equality of nature consists in the composition of man in two: one is the apparent or extrinsic equality, the other is the intrinsic equality, and is the nature of the soul itself, about which we spoke above.

The apparent quality consists in the equal composition of the body itself from four humors, which are blood, warm and moist by nature, namely of the air; and choler, warm and dry by nature of fire; and phlegm, whose nature is cold and moist by nature of water; and melancholy, cold and dry by nature of earth.

The equality of these humors is therefore the cause of the union of the soul with the body; but if the apparent equality is corrupted, then consequently the bond of the soul with the body is corrupted, and it happens that the soul is then separated from the body, and this separation is called death.

But this does not happen from any slight departure from equality unless it is considerable in quantity: if the quantity is small, from this perhaps arises sickness and disturbance until suitable medicines restore them again to equality; and perhaps there are certain illnesses to which the devil is joined by the humor going out from the temperament and disturbing the health itself, and this happens mostly in illnesses arising from choler, whose cause is this: for, as we said, the nature of choler is warm and dry, like fire; but the body of the devil is composed of two things, namely fire and air; and we said above that every subtle thing enters every gross thing, therefore, since fire is subtler than air, it is clear that the apparent body of the devil is air, its hidden part is fire; and this is the cause of its concealment from human sight, since the medium through which we see all things is air, which is joined to our eye.

Therefore, since within the devil there is the nature of fire, it is clear that it is contrary and hostile to the nature of the soul, which is the nature of equality: thus when sickness happens to the body from the nature of choler in the body, and since the devil, hidden within, is of the nature of that choler, he joins with the choler and increases its dominion over the other humors, so that the soul may predominate less and less, withdraw from the body, and be separated from it. But if one knew how to bring down the light, whose nature is contrary to the hidden nature of the devil, then the perfection of the devil would be corrupted and destroyed, the sickness would depart from man, health would return, and man would stand firm and peaceful.

But the method by which a person makes the spirit itself descend is that he knows the nature of the Planet whose spirit he seeks to bring down, and its color, smell, and taste; then he prepares the visible part of his own body with the above-mentioned color, taste, and smell: so that, as the color is, he takes clothing of that color, and opens the hidden part of his body with nature and taste, and takes food strengthening his body from change, and approaches the degree of equality; and this must not be hidden from him who seeks to make the spirit descend; nor should he desist or cease from this until he makes his stomach accept that food, and not reject it, and not desire another which would prevent his appetite, and that at every hour of that Planet he be lifted directly and humbling himself asks the Creator that He fulfill his will; and when his will and desire are fulfilled, he gives thanks to his Creator.

Then he observes when that star enters directly into its own sign, so that it does not enter through the contrary Planet. Afterwards, he makes from the body that is of that Planet a cross, pierced from top to bottom, and stands upon two feet and rides upon a figure suitable to the matter sought, such as above a lion or serpent, for war or victory, or to cause fear in the enemy; or above a bird, for salvation from great labors; or upon a throne seeking exaltation.

The reason why we take the form of the cross is that we do not know the thing to which the spirit whose descent we seek is similar; but we know that the spirit is a created thing, and every perfect thing is a body, and a body has length and breadth like a cross; and we have said before that every nature embraces a nature similar to itself. This is therefore the reason why we prefer the figure of the cross to other figures in this matter; and if you wish to subject some to obey you as servants to their master, this is the figure: O IIΧΟ OIL 5 1.

Then if he is a man and knows the star dominating his nativity, he makes the figure of that man from the mineral that is from the part of that planet, in its hour, and he looks toward the sign of the star contrary to him in nature, and is with it in the same sign; and if that star is fortunate, then afterwards place this figure which is to the first OV 12LI 5 II.

And if that star is not dominant, then we make seven figures from seven stones, which are of the nature of the seven planets; and if they are of the nature of Saturn, arsenic of the nature of Jupiter, magnet of the nature of Mars, ruby of the nature of the Sun, alum of the nature of Venus; crystal of Mercury and the Moon.

From each is made one figure, in the hour of its Planet; and when these stones face the cross in the east, we see that the figure in nature is enlivened, and when the spirit is bound to the cross, it has the power of a human figure above that figure, whether it is a man or not.

Then we take the censer made from the mineral of which we made the cross, and it shall be perforated at the top so that smoke cannot escape anywhere else; afterwards, we take a bright and clean bed, uncovered but outdoors, and it is surrounded by herbs which are of the nature of the Planet whose spirit we seek, and nothing else shall be in that place, neither far nor near. Also, we take incense which is of the nature of that plant and place it in the aforementioned censer so that the direct smoke may rise through the hole of the cross, and all these things shall be done in the hour of the planet whose spirit we seek to descend. Then the superior spirit is bound to its similar, an example of which is like when we have two lit candles, of which one extinguished is placed directly under the other still lit; then, as the smoke rises from the lower to the upper, the flame descends from the upper to the lower and lights it, and this is the method of causing the spirit to descend.

When therefore the spirit itself descends, which is the soul of an animal or spiritual, and finds the prepared body as we said, it penetrates into it and binds itself to the corporeal soul, because the corporeal soul is hidden in every body due to the similarity of one of these souls with another in nature. But if the body is not properly prepared, it corrupts and destroys it, and then returns to its place. Also, it is necessary to dissolve the body from which the cross was made with water equal in nature to that of the putrefaction, until its corporeal soul is tempered with its body; then it is fumigated with incense so that its body is bound to its element, and the same cause of binding occurs in the lower body until it attaches to its similar. And you should know that each Planet has a half-end and its own proper disposition; afterwards, if he whose disposition you seek also has a general disposition, the effect will be greater and stronger. And know that the spiritual soul is not bound with the corporeal soul except by a similar mode; this and that is one of the greatest secrets, but the binding of the spiritual soul with the spiritual, which is the human soul, must be done by this mode; because when the ruling Planet of any nativity disposes it in the hour of binding the soul with its body, when the body is changed from corporality to spirituality, as if the body becomes spiritual, then to animality, as if from spiritual it becomes animal, the soul is bound with its element and sees and knows what it could not see nor know before.

But if the ruling planet of any nativity is unfortunate, that man will be weak, as long as the power of his body predominates over the strength of his soul, or even if they are equal; but after the soul acquires dominion over its body, then those misfortunes cannot harm, nor will any impediment come from this.

After he has known this, he will take garments of appropriate color and food, and accustom himself to those foods until his stomach makes him receive them and desires no other, gradually nourishing himself little by little, namely first to eat once a day, then once every two days, then in three, until he reaches the point where he can eat only once in eight days without weariness and fatigue from the star, and he will arrive at the sought goal. Afterwards, know that the descent of the spirit is twofold.

The first is the descent of its descent, and the second is obedience.

The first has been sufficiently explained: but the descent of obedience is the promptness of service of the descending spirit with respect to him to whom it descends to carry out his will or command. It is also one of the greatest secrets that man knows that all coarse things become subtle, and every step becomes spirit, and every spirit becomes soul, and its subtilization divides itself into two, namely into that which is imitated into another nature by the combustion of fire and element, and that which is not changed by the combustion of fire but only operates; and this second is what the Philosophers sought.

For all things which require sublimation from composed things are three: namely, the bodily body, the first minerals, whose subtilization is from its exterior to interior; the second is the spiritual body, that is the plant, whose subtilization is from both simultaneously; the third is the animal, whose sublimation is from its interior to exterior, if God wills.

Here ends the Greater Key of Wisdom.

LATIN VERSION

ARTEFII CLAVIS MAIORIS SAPIENTIAE.

TYPOGRAPHVS PARIsiensis Lectori.

Natura hominem πολιτικὸν ζώον credunt: ego imbecillitate, &: Cum enim naturæ suæ defectum animaduerteret, huic morbo mederi, à societate sumpto auxilio, tota ope contendit : dehinc varia hominum ingenia, diuersas artes inuenire necessitate instigante, ciuitates inimicitiis ortis, ad sua tuenda designarunt: postremum augescente malitia, aut adulta luxuria, reliquas artes aut casus reperit, aut inuenit solertia: in quibus conseruandis aut ampliandis, aut reformandis, tota studiorum hominum vita teritur: vt cum pro ratione finis appetitus sint diuersi, & voluntas inapparens, tanquam verum feratur: Multi ad ματαιοτέχνιαν declinauere Χρχιτεκτονικῶς non satis cognito fine, ad subalternas confugere, & vt Penelopes proci cum domina non possent potiri, ad ancillas conuersi sunt, sic ii quibus non ita fœlix ingenium natura largita est, vt veritatem ipsum viderent oculis, aut certe cum vidissent eius adipiscendæ spe frustrati, quod præ manibus erat acceperunt, nescio an satis tuto consilio.

Difficultas etenim rerum operis adgrediendi, viam præcludere non debet, iis quibus adhuc aliquid superest magnanimitatis: verum cum aliorum causa, tum propria vtilitatis gratia, quamplurimæ artes repertæ sint, ea quæ plus reipublicæ sunt profuturæ, maiori studio ab hominibus debent exquiri siullæa sane quæ leuandis humanæ naturæ incommodis penuria & morbo, operam consumit, quam ΐεραν τέχνίω καὶ vocant.

In qua cum prioris æui homines aliquid inuenissent, ea literis mandarunt vnde tot præclara huius artis volumina, ad nostra vsque tempora peruenerunt.

Ego horum exemplo quantum in me fuit vt omnibus prodesse possem, si non in componendis, saltem in publicandis operibus, quæ desiderabantur, operam dedi: verum cum in omnibus sit aliquid arduum, quo non superato, cum labore reparatur: si hac in arte, quod præcipuum est, agens ab omnibus est desideratum: sed quonam pacto haberetur, Iohannes Pontanus in hac breui epistola, quam de ea arte composuit, ad Artesium remisit.

Quod cum animaduerterem, & exemplar huius in manus meas peruenisset, nolui te hac luce priuari: sic enim docuit nos Heliodorus ad Heraclium de arte tale ingenium esse sapientum.

Μηδὲν φθονοῦτες τοῖς θέλοισι μανθάνειν.

Sic virtus, & quæ pulchro nomine digna propagatione gaudent, & bonitas sui diffusiua esse creditur Horum expellentem sententiam qui sibi solis sapere volunt.

Quis autem fuerit hic Artesius, non satis constat, hunc Iudæum quidam existimant, de eo quædam apud Rogerium Bacchonem, & Cardanum: quantæ autem eruditionis, hic liber poterit demonstrare, in quo si sint aliqua præter fidem, esse ænigmata tibi persuadeas velim: quæque vero plane physica sunt, mira sunt arte contexta.

In hoc sane illud να ἀρχιόρεως perdifficile factu, facili demonstratione patescit ἐὰν μὴ ἢ σωναρᾶσις σερέων Σπολεσθὴ εἰς κένον ματαίον πᾶς ὁ πὸν: Sane innumera alia hoc in libro explicantur, quæ non nisi summo cum labore possent persici & intelligi.

Hæc ergo, lector, æqui bonique consule, & quod præcipuum est, amplectere: si nobis quid melioris notæ superuenerit, tu & eius particeps eris. Anno 1609.

Vale.

ARTEFIUS

INCIPIT LIBER QUI

CLAVIS MAIORIS sapientiæ dicitur.

DIuiditur autem iste liber in tria capitula, nec vnum completur, sine aliis.

Primum enim indiget secundo & tertio; secundum primo & tertio; & tertium primo & secundo.

Primum enim tractat de compositione elementorum, superiorum ac inferiorum, & naturarum æqualium & inæqualium, & conuersione eorum adinuicem, & generatione.

Secundum tractat de generatione corporum mineralium, tam naturalium quam artificialium.

Tertium, de generatione plantarum & animalium, & adligamento corporis cum spiritu, & etiam animæ, & ipsius animalis cum animali.

Laudemus igitur Deum, qui est inspector omnium nec est quod lateat ipsum, ipse enim est adligatus suis creaturis per verbum suum, & separatus ab eis in quantum ipsas transcendit, nec enim puto qƺ aliquid creauerit sibi simile vel æquale, & de magnis beneficiis.

Et maximum est illud, quod ipse allegauit corpus nostrum tum subtilissimo omnium elementorum, scilicet anima; quæ videt occulta manifeste, dum tamen virtutes ipsius corporis ipsi non prædominentur: quanto enim magis fortificantur ipsius corporis vires, tanto magis animæ virtutes necesse est debilitari, & quanto magis ipsum corpus alteratur, tanto magis ipsius animæ subtiliatur intuitus.

Et propterea dixit magister noster Belenius Philosophus, ponas lumen tuum in vase vitreo claro, & nota quod omnis sapientia mundi huius circa ista tria versatur, scilicet circa adligamentum animæ corporalis cum anima corporali, & animæ spiritualis cum anima corporali, & spiritualis cum spirituali. Sed adligamentum animæ corporalis cum corporali propinquius est & facilius quam spiritualis cum spirituali.

De isto enim tertio pauca scribere voluerunt sapientes Antiqui; dixerunt enim, nullum ad ipsius scientiam posse pertingere, nisi fuerit natura sua diuina & spiritualis, & sua natiuitas.

Etenim postea dixerunt communiter sapientes omnes Antiqui sine diuersitate, quod illud quod est superius, est sicut illud quod est inferius; & è conuerso; & omne subtile est ex grosso, & grossum ex subtili; & omnis compositio mundi siue maioris, siue medii, siue minoris est vna compositio.

Et scias quod omne adligamentum rerum mundanarum est sicut adligamentum numeri, videlic. ex vnitatibus, denariis, centenariis, & millenariis.

Ex digitis enim numeratur primus articulus, dicendo sic vnum, duo, tria, quatuor, quæ simul adgregata denarium constituunt; similiter si dicas decem, viginti, triginta, quadraginta, ex his numeris simul adgregatis centenarius exoritur; hoc idem etiam in centenariis & millenariis apparet, cum enim numerus nihil aliud sit, qua adligamentum vnius rei ad aliam, manifestum est, quod vnitas numeri non sortitur naturam: cum ergo binarium acceperimus, quoniam numerus primus est, & ipsum in duo æqualia diuiserimus, manifesti est ipsius partem alteram vnitatem existere; quam si binario addere voluerimus, ternarius inde prouenit: si vero binarium duplaris, quaternarius inde nascetur, & quaternario si vnitatem addideris, quinarium tibi producet, si vero ternarium eidem addideris, septenarium inde recipies, qui vnitate superaddita octonarium tibi procreabit, si item vnitatem addideris, nouenarium recipies, si vero binarium, denarium numerum tibi procreabit; eodem modo centenarii ex denariis: millenarii vero ex centenariis procreantur.

Vna vero die vocauit me magister meus Belenius Philosophus, & dixit mihi, eia fili, spero te esse hominem spiritualis intellectus, & quod poteris pertingere ad gradum supremum sapientiæ.

Interrogo te ergo, & tu responde mihi?

Et dixi ei: Eia pater misericors ac magister honorande, interroga discipulum & ego sicut potero, respondebo tibi.

Et dixit: In quot genera diuiditur Natura?

Et dixi: in quatuor.

Et ille: quæ sunt illa quatuor?

Et dixi: simplex, ac simplex de simplici, compositum de simplici, & compositum de composito.

Et dixit: Quod ipsorum est primum?

Et dixi, simplex. Et ait: & quid est illud simplex?

Et dixi: Duæ naturæ, quantum vna est agens, altera patiens.

Et ait; quæ sunt illæ duæ naturæ?

Et dixi; Prima earum est natura caloris, & secunda frigiditatis. Quid natura caloris? est actiua; frigiditatis vero passiua.

Et dixit: Quid est post simplex ? & dixi, simplex de simplici.

Et dixit: Quid est illud?

Et dixi, natura caloris & natura humiditatis, & natura frigiditatis, & natura siccitatis: Et ait: Quomodo generantur duæ illæ naturæ?

Et dixi: Creator omnium in principio absque sermonis prolatione dixit, sit creatura talis; postea creata est à Deo natura siue materia prima, de qua Aristoteles in primo Physicorum, & Plato in Timæo consimiliter scripserunt, quod est primum passiuum, siue receptiuum; quæ non magna, nec parua, nec subtilis nec grossa, nec mouens nec quiescens esse potuit, nec alia debet nominatione determinari, nec rei cuilibet adsimilari: in qua quidem omnia principaliter exstiterunt, scilicet in potentia, quæ est, esse medium inter esse actu & perficere, & nullo modo esse.

Et vt ad actum reduceretur creauit creaturam secundam, scilicet causam agentem similem scilicet orbi cœlesti, quam lucem appellare decreuit.

Hæc autem lux Sphæram quandam creaturam primam intra sui concauitatem obtinebat.

Huius vero naturæ & primæ creaturæ alia creatura erat caloris & motus, vnde patet aliam primam esse frigiditatis ac siccitatis: & quia naturæ illæ erant adinuicem approximatæ, repercussit calor frigiditatem, & constrinxit se frigiditas condensando seipsam : & quia de natura caloris & cuiuslibet rei subtilis est penetrare, penetrauit calor vsque ad centrum frigiditatis: & quia cuiuslibet rei finis est contrarium, eius motui autem opponitur tam motus quam quies.

Ideoque motui sisti, qui fuit ad centrum siue ad medium, successit alius motus in medio: temperauit enim se vna pars caloris cum parte frigiditatis sibi æquali, & euenit ex ea tempera tura natura humiditatis; & quia natura eius fuit media inter naturam caloris & frigiditatis, ideoque locum medium sortita est inter vtrumque, & fuit motus ille à centro vsq; ad medium, cui iterum successit alius motus, scilicet à summo ad medium, & à medio ad medium inter minimum & supremum, ac iterum ab infimo ad medium, hoc est à medio ad medium, inter medium & infimum: temperauit enim se vna pars caloris cum parte humiditatis sibi æquali, & venit ex isto temperamento natura caloris ac humiditatis, cuius locus, vt prædiximus, medius erat inter locum caloris & humiditatis: & quia, vt prædiximus, natura humiditatis est composita ex vna parte caloris & vna humiditatis vel frigiditatis sibi æquali, sequitur, quod natura caloris & humiditatis est vna pars frigiditatis, & tres caloris, eodem modo natura frigiditatis & humiditatis est adgregata ex natura frigiditatis, ac natura humiditatis æqualiter.

Et quia natura humiditatis medietas est caloris & medietas frigiditatis, sequitur quod natura frigiditatis & humiditatis tres quartæ sunt frigiditatis & vna caloris.

Iam igitur habemus secundam sphæram primæ naturæ quatuor sphærarum, de quibus supra: quarum prima frigiditatis & humiditatis, quam sphæram spiritus appellauerunt sapientes Antiqui: supra ista, æqualitatis naturam, quam sphæram animæ nuncupauerunt, postmodum vero naturam caloris & humiditatis, quam sphæram tertiam appellauerunt, & postremo naturam caloris & siccitatis, quam sphæram appellauerunt quartam, & hic fixatur: & quia, vt prædixi, cum fuerint commixtæ illæ duæ naturæ primæ adinuicem, non fuit ex tunc motus à sursum ad deorsum, & è conuerso, sed mouebantur omnes sphæræ motu circulari.

Iam ante diximus, quod cuilibet rei omnium extremum sibi contrariatur, & quod motui à sursum ad deorsum non solum opponitur motus à deorsum ad sursum, sed etiam quieti; ideoque diximus, quod vna pars caloris quæ non se commiscuerat cum natura frigiditatis ad generationem humiditatis remansit inferius admixta frigiditati, & quia non est dare vacuum in natura, ideoque loco istius caloris qui descenderat, subuenit quædam pars frigiditatis sibi æqualis.

Iam igitur patet, quod istæ sphæræ erant adinuicem connexæ. Infima enim erat sphæra frigiditatis & siccitatis, in qua nihil est caloris: post ipsam vero sequitur sphæra frigiditatis & humiditatis, cum tres quartæ sunt frigiditatis & vna caloris:postmodum vero sphæra æqualitatis, quæ est sphæra animæ, cuius medietas est de natura caloris, & medietas altera de natura humiditatis.

Iam autem diximus, quod sphæra humiditatis medietas est de natura caloris, & vna quarta de natura frigiditatis: Sphæra vero suprema quæ est post istam, est de natura caloris & siccitatis, nec est in ea aliquid frigiditatis. Sic igitur vides, quomodo spheræ istæ adinuicem ordinantur.

Et ille: Iam mihi naturas caloris & frigiditatis sufficienter demonstrasti: sed quid est siccitas nondum exposuisti?

Et ego: siccitas sola est priuatio humiditatis, in quo enim nulla est humiditas, siccum appellamus.

Et ille: iam mihi sufficienter explanasti: Quid sit simplex, & quid simplex de simplici.

Nunc ergo mihi dic, quid post illud?

Et dixi: compositum de simplici. Et ille: quid est illud?

Et ego: quatuor elementa, quæ sunt ignis, aer, aqua, terra. At ille: quomodo generantur ista quatuor elementa? & ego: temperauit se natura ignis scilicet caloris & siccitatis cum natura caloris & humiditatis, & venit ex ipso temperamento æquali elementum ignis: & se temperauit elementum ignis cum natura humiditatis, & venit ex isto temperamento elementum aeris, & temperauit se elementum aeris cum natura frigiditatis & humiditatis, & venit ex ipso temperamento elementum aquæ: & temperauit se elementum aquæ cum natura frigiditatis & siccitatis, & venit ex ipso temperamento elementum terræ.

Ignis ergo est aer subtilis, calidus, & siccus; aer est ignis grossus, calidus, & humidus: aqua est aer grossus, frigidus, & humidus: & aer est aqua subtilis calida & humida: & aqua est terra subtilis, frigida & humida: terra est aqua grossa, frigida & sicca.

Et ille: quid est illud quod est compositum de simplici?

Et ego: compositum de composito ?

Et ille: quid est illud & ego: est corpus animæ corporalis, quod est de corpore animali, & corpus spiritus corporalis.

Et ille: quid est spiritus corporis animalis, & quomodo generantur ista corpora ex elementis ?

Et ego: temperauit se elementum ignis cum elemento aeris, & venit ex ipso temperamento æquali corpus animæ corporalis : & temperauit se elementum aquæ cum animæ corporali, & venit ex isto temperamento corpus spiritus corporalis: & temperauit se corpus spiritus corporalis cum eleméto terræ, & venit ex isto téperaméto terræ corpus corporalis corporis.

Postmodum vero cum isto corpore corporali commiscuit se aqua, & temperauit se cum subtiliori ipsius, & venit ex isto temperamento corpus corporis spiritualis : & temperauit se aer cum subtili ipsius corporis spiritualis, & venit ex isto temperamento corpus animale, & temperauit se ignis cum isto corpore animali, & commiscuit se cum subtiliori ipsius, & veniet ex isto temperamento corpus animæ corporalis: & hoc est, quod quærebant sapientes Antiqui: & ipsum est, ex cuius temperamento cum æquali sibi temperamento aquæ generatur, vt prædiximus, corpus spiritus corporis æqualis: ex cuius temperamento cũ æquali parte terræ generatur corpus æquale, quod Sol est; & nisi essent diuersæ actiones & influentiæ corporum cœlestium in ipsa inferiora, omnia corpora mineralia essent aurű.

Omnia etenim sunt ex eodem, & animæ & spiritus eorum sunt de vna re, nec differunt, nisi secundum magis, & minus, & secundum diuersitatem decoctionis maioris vel minoris.

Diuersitas igitur eorum est ex diuersitate influentiarum corporum cœlestium in ista inferiora, sicut etiam numerus eorum est secundum numerum septem planetarum: à natura colores, & odores, & sapores, & accidentia cætera.

Plumbum enim de parte Saturni, sua natura est vt sua natura.

Stannum vero est de parte Iouis, sua natura vt sua natura.

Ferrum vero de parte Martis, sua natura vt sua natura.

Aurum vero de parte Solis, sua natura vt sua natura.

Argentum viuum de parte Mercurii, sua natura vt sua natura.

Argétum ex parte Lunæ, sua natura est vt sua natura: Cuprum vero de parte Veneris, sua natura vt sua natura.

Postea vero ista metalla mineralia mutantur adinuicem, & alterantur sicut elementa, ex quibus consistunt.

Ignis enim fit aer, & aer fit ignis, similiter aer fit aqua, & aqua fit aer, & aqua fit terra, & terra fit aqua, & sic de aliis.

Et scias quod omne compositum ex elementis, habet in se quatuor naturas, videlicet, caliditatem, frigiditatem, humiditatem, & siccitatem.

Quod si dicat aliquis, aliquod esse compositum ex duabus tantummodo naturis istarum naturarum quatuor: dicemus ergo quod ex frigiditate & siccitate tantum: quia igitur illud compositum est frigidum, & siccum vt terra, ergo erit sua natura de natura terræ, tactus & odor vt terra.

Quod si quis dicat, qƺ terra est frigida & sicca in quarto gradu, & illud compositum non est in quarto?

Dicemus, quod quoniam sunt duo eiusdem complexionis, & non differunt nisi secundum gradus, videlicet quod vnum est in quarto gradu, & reliquum in primo, secūdo vel tertio, impossibile est illum, qui est in primo, secundo vel tertio gradu, prohiberi quin pertingat ad gradum quartum, nisi propter admixtionem qualitatis contrariæ, ergo non fuit mixtum ex duobus tantum, sed ex tribus, quibus contrarium est positum.

Et debes scire quod omne minerale est subtile terreum, & planta est subtilis minera, & corpus animale subtile ipsius plantæ.

Ex elementis autem generantur corpora mineralia: & ex mineralibus generantur plantæ: & ex plantis animalia: & quia vnumquodque resoluitur in ea, ex quibus componitur, ideo animalia quum resoluuntur, generantur ex iis plantæ, via resolutionis: codem modo ex plantis mineræ: mineræ autem ex elementis, elementa in naturas resolui necesse est.

Et ille: dic mihi quid est spissum, & quid est subtile, siue delicatum?

Et ego: spissum est corpus, subtile autem est spiritus, & subtile spiritus animalis est natura: Et ille: Quid est corpus?

Et ego: corpus est illud, quod habet aliquid adparens & aliquid latens. Illud vero quod adparens est, est eius grossicies & spissitudo: quod vero latet, est eius subtile, scilicet spiritus & anima.

Corpus autem est ex compositione animæ & spiritus & corporis, corpore autem corrupto ex tunc illud quod dicebatur spiritus postea corpus nuncupatur, & illud quod anima dicebatur postea spiritus appellatur. Maximum est igitur quoniam spiritus est subtile ipsius corporis : anima vero ipsius spiritus est subtile : omnia autem ista adinuicem, vt prædiximus, per viam compositionis siue resolutionis generantur, & adinuicem separantur, & alterantur, sicut etiam de ipsis elementis prædiximus.

Hoc autem non fit, nisi per ingressum vnius naturæ in aliam: verbigratia, cum aliquid volumus esse frigidum & siccum in quarto gradu, & intendimus de quarto gradu frigiditatis, & siccitatis ad eandem frigiditatem & humiditatem, mutabimus ipsum in primis de quarto gradu frigiditatis & humiditatis ad gradum eiusdem tertium, deinde ad secundum, deinde ad tertium, postremo vero ad æqualem inter prædicta, deinde ad gradum primum variamenti versus humiditatem, deinde ad secundum, deinde ad tertium, deinde vero ad gradum frigiditatis, & humiditatis quartum : & si iterum mutare voluerimus ad gradum quartum frigiditatis vel caliditatis & humiditatis, mutabimus ipsum in primis ad gradum frigiditatis: deinde ad secundum, deinde ad tertium, deinde vero ad gradum æqualitatis in frigiditate & humiditate; & deinde ad gradum primum variamenti, ex parte caloris, deinde ad secundum, deinde ad tertium, deinde ad quartum, donec fiat calidum & humidum in quarto gradu.

Quod si iterum ad eundem gradum caloris & siccitatem ipsum reducemus, dehinc ad secundum, deinde ad primum, postremo vero ad gradum æqualitatis in calore, & humiditate: postea ad gradum primum siccitatis, deinde vero ad secundum, deinde ad tertiũ, deinde ad quartum, sic ergo ipsum mutabimus de gradu quarto frigiditatis, ac diuersitas eorum est, secundum diuersitatem corporum supracœlestium ipsi correspondentium à natura, & odorum & saporum semper secundum similitudinem.

Dicamus ergo, in principio creationis fuit quilibet planetarum in directo sui signo in orbe signorum, & operabantur ergo operationes, & descenderunt in terram, donec generarentur corpora mineralia ipsis proportionabilia, & postea mouebantur ista corpora supercœlestia: hinc ista habitudo & respectus inferiorum: & corrumpebantur mineralia prius generata, & postea rediit ille adspectus corporum supercœlestium respectu inferiorum, & generabantur plantæ ex eadem materia, quæ prius erat sub forma corporum mineralium, & postremo abscessit motus iste, & corrumpebantur plantæ, & rediit tertio moius iste, & generabantur ex istis plantis animalia.

Diximus igitur quod natura corporum mineralium est sicut natura terrae frigida & sicca: natura plantarum est de natura aquæ, frigida & humida: natura animalium sicut natura aeris, calida & humida.

Quod si obijciat quis & dicat: quomodo dixisti, quod natura mineralium est frigida & sicca, & natura plantarum frigida & humida, quod nos videmus multa ex mineralibus occidere animalia per calorem suum?

Ad hæc itaque respõdemus, quod si inueniatur minerale occidens animale per caliditatem suam, quod planeta, qui est de illa minera, multo magis operationes operabatur, & similiter omne quod fuit de illo planeta, plus quam planeta: si ergo temperetur ex planeta, qui ex ea est, dicimus quod in operatione eius est frigida: & si iterum temperetur planeta & animal in comparatione eius, reperietur frigida & humida.

CAP. II.

De generatione mineralium.

DIcamus ergo de generatione mineralium: dixerűt autem quidam, quod natura mineralium omnium est argentum viuum cum sulphure, & dixerunt quidá quod radix ipsorum mineralium est argentum viuum cum sulphure.

Præparemus ergo radicem, donec perueniamus ad ramos: & causa istius opinionis est, quod ipsi considerauerunt naturas corporum mineralium superficie tenus: nam in profundo, si rexissent secreta naturæ, nunquam incidissent in tales opiniones.

Dicimus igitur, quod dato, quod argentum viuum & sulphur sint prima naturalia corporum mineralium ante congelationem suam, tamen post congelationem argenti viui & sulphuris impossibile est ex ipsis corporibus mineralibus generari, nam congelans suum congelandum iam ipsum alterauit in suam naturam.

Cuius exemplum est de compositione saponis: si enim accipiatur aqua extracta à cineribus, & oleum eum quibusdam aliis, & decoquatur decoctione certa, generatur ex iis sapo, & si acciperetur vnumquodque per se, & decoqueretur donec congelaretur, & postea laboraret quis ex ipsis saponem componere, non posset: sulphur autem in primo erat aqua natura eius frigida ac humida, & postea conuersa est in aerem, cuius natura est calida & humida: postmodum vero in ignem, cuius natura est calida & sicca: postmodum vero cum ipso igne temperauit se aqua, & fuit compositio masculi & fœminæ: & dicimus ergo quod dato quod natura siue radix mineralium sit argentum viuum cum sulphure, non tamen debemus accipere ipsum, ex quo sunt corpora mineralia, sed magis debemus ipsum accipere quod est ex ipsis corporibus mineralibus, cuius exemplum est manifestum in plantis.

Scimus enim quod generatio plantæ est ex aqua cum subtili terreo, vt prædiximus, & tamen si acciperemus aquam & terram, nunquam generaremus plantam: non ergo accipimus illud ex quo est planta, sed illud ex quo animal, quod est ex planta, scilicet ouum ipsius, postquam scimus, quod illud ouum generatur ex terreo subtili cum mixtione ipsius aquæ, commedamus ipsum terræ, donec illud quod fuit diminutum compleatur.

Et dicimus etiam quod generatio metallorum in ventre terræ fit, hoc modo, cum Sol agat in ista inferiora, per caliditatem suam calefacit terram, & remanet pars ipsius caloris in interioribus terræ, & cum ascenderit Sol super terram, & inuenit quod calor sit in terra absconditus, calorem sibi similem naturaliter, oportet ascendere vna cum parte caloris nouiter generati, cum occurrerit sibi aliqua pars aquæ soluit ipsam, & conuertit in vaporem, qui quidé vapor mouetur ascendendo donec currat super ipsum calor proportionabilis: cum vero descenderit Sol verlus occidentem, diminuitur calor proportionabilis, donec condensetur vapor & descendat distillando.

Sole autem iterum oriente, caloreque ipsius iterum, vt prius deficiente descendet secundo distillando, sic quod non cessat continuo subtiliare & distillare, donec totum oleum soluatur, quod in ista aqua consistit, & commisceatur ipsi aqua, totumque conuertatur in oleum.

Quod si inuenerit aliquam partem sulphuris, & admisceatur : & si ergo fuerit quantitas aquæ æqualis quantitati ipsius sulphuris, ac paulo magis, scilic. quantum sufficiat ipsum incorporare, generatur ex eo aurum vel argentum, & sic de aliis secundum quantitatem ipsius decoctionis.

Si vero fuerit quantitas sulphuris maior quantitati ipsius aquæ, generabitur ex iis corpus minerale, quod non erit de minera ipsorum septem.

Iam diximus quod in generatione artificiali ipsorum corporum mineralium non quærimus illud ex quo sunt ipsa corpora, sed illud quod est ex ipsis, sicut etiam in ipsis plantis exemplificauimus: diximus enim, quod accipimus ouum ipsius plantæ, & consideramus de quo est illud ouum, & postquam scimus illud esse ex terreo subtili cum mixtione aquæ, commendamus ipsum terræ, sic etiam in mineralibus accipimus ouum ipsum, & deinde consideramus vnde generatur ipsum, & postquã scimus vnde generatur, scimus etiam quod ex iisdem oportet nutriri: scimus autem quod ipsum ex quo generatur ouum illud, est admixtio ignis cum aqua.

Et etiam diximus, quod sine complexione maris & fœminæ, nihil omnino generatur.

Cum autem præparemus ipsum præparatione sibi debita, generatur ex ipso aurum, vel argentum: & scire debes quod hoc non fit sine putrefactione & solutione, sicut nec in plantis contingit, non enim ingredietur super ipsum ignis sine humiditate.

Illud igitur quod est causa ingrediendi, est calidum & humidum, non enim adligatur natura nisi naturæ sibi propinquiori: cum ergo occurrerit humiditas soluentis humiditati ipsius soluti, adligatur humiditas humiditati, sed nos non soluimus totum compositum, quia si solueremus ipsum simul, tunc ouum corrumperemus ipsum, sed soluimus partem post partem, donec illud, quod est contrarium naturæ soluentis recedat à soluto.

Et scias quod in hoc differt ouum plantæ ab ouo mineræ, nã ouum minerale non putrefit absque contritione siue molitione, non enim ingreditur soluentis humiditas in ipsum absque molitione, propter adhærentiam partium ipsius soluti adinuicem. In ouo autem plantæ, si moleremus ipsum, corrumperemus figurã ipsius plantæ, quæ est in ipso in potentia: ignis vero, vt prædiximus, quamuis sit agens in corporibus tamen aer, siue caliditas & humiditas edat causa ingrediendi, sed quia humiditas ipsius aeris est contraria siccitati ipsius, ideo requiritur necessario aquæ ipsius frigiditas, quæ temperet ipsum: & quia aqua non fixatur in igne sine terra, ideo requiritur etiam necessario terra quæ figat ipsam aquam.

Iam autem sæpe diximus superius quod generatio non fit sine maris, & fœminæ coniunctione.

Ignis autem & aer sunt masculina, aqua autem & terra sunt fœminina, & ignis est masculus aquæ, & aer est masculus terræ: sed ignis non admiscetur terræ absque mediatore aere: est enim aer propinquus igni ratione suæ caliditatis, & est vicinus aquæ ratione suæ humiditatis.

Iam autem diximus frequenter, quod naturam natura amplectitur sibi similem: aer ergo ratione siue concordia, cum vtroque factus est concordans inter vtrofque generationis, similiter vero aer contrariatur terræ, secundum vtramque qualitatem: est enim aer calidus & humidus vt prædiximus, terra autem frigida & sicca, aqua vero ratione suæ frigiditatis conuenit cum terra, ratione vero suæ humiditatis conuenit cum aere, aqua igitur inter aerem & terram est medians & concordiam generans. Manifestum igitur est, quod aqua & ignis non copulantur adinuicem, sine aere mediante in vna extremitate, & etiam sine mediante terra in alia sua extremitate: & hoc est quod volumus.

Quia igitur iam declarauimus ouum minerale generari ex igne & aqua, & etiam per consequens ex iisdem nutriri.

Ignis vero, vt prædiximus, est masculus, aqua vero est fœmina, nunc est nostrum nobis inuestigare istum masculum donec inueniamus ipsum.

Iam autem diximus superius, quod corpora mineralia sunt de natura terræ, cuius natura est frigiditas & siccitas: quod quantitas ignis in ipso est modica nisi in potentia, minor quam ad gradum secundum : quoniam est de vegetabili actu, inueniūt eius naturam frigidam & humidam : & quia natura frigidæ & humidæ tres quattæ sunt frigiditatis & vna caloris, & illa etiam quarta caloris est profunda in illis tribus partibus siccitatis, ideoque ascendendum est ad tertium gradum, quod est animal; & quia natura animalis, vt prædiximus, est calida & humida, manifestum est igitur, quod sint tres quartæ caloris & vna quarta humiditatis sed quia animal quando completur est commixtum, & temperatum suum grossum cum ipsius subtili, ideo non est illi motus à deorsū ad sursum ideoque accipimus de animali illud quod non completur, & commendamus cucurbitæ & alembicis ad distillandum, & distillamus primum aquam, cuius manifestum est albedo, ignis vero occultum est rubedo: deinde distillamus aerem, cuius manifestum est citrinitas, eius vero occultum est viriditas, & remanet ignis in ipsa terra.