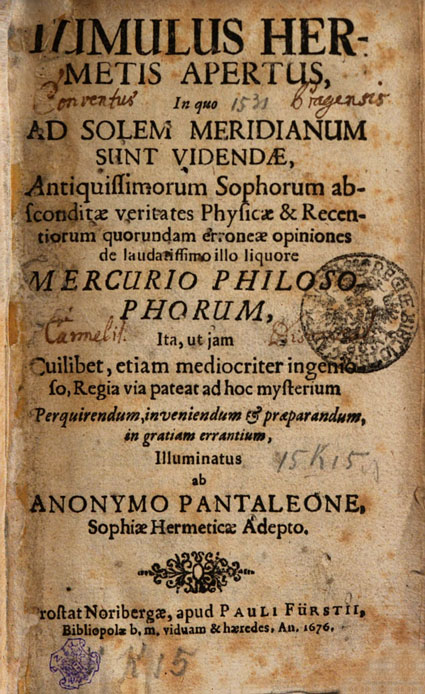

The Open Tomb of Hermes - Tumulus Hermetis Apertus

In which, in the year 1531,

are to be seen in the noonday sun

the hidden physical truths of the most ancient Sages,

and the erroneous opinions of certain more recent ones

about that most praiseworthy liquor,

Mercury of the Philosophers.

So that now even to anyone of only moderate wit,

the royal road lies open to seek out, to discover, and to prepare this mystery,

for the sake of the erring,

Made clear by Anonymous Pantaleon,

an Adept of Hermetic Wisdom.

Published at Nuremberg, by the widow and heirs of Paul Fürst, bookseller.

Year 1676.

Translated to English by Mitko Janeski

Epitaph of the Tomb

Kind reader, whoever you may be, attend. Here you may behold a monument of Natural Truth, born indeed by the kindly favor of Heaven, with human industry as its midwife, but slain by the deadly crime of envy, at the harsh command of Fate. While it lived, brighter than gems or gold, it was the mother of wonders. Now, made a fable of the crowd, it rests near Acheron, in a horrid and inaccessible place. Its tomb is guarded in palpable darkness by mournful owls along with the dreadful powers of hell. If by chance you seek to examine its bones, know this: no one clears a path here unless led by the guidance of Heaven; under penalty of final ruin, do not enter, unless with an enlightened mind and accompanied by a faithful friend.

To Momus

Indulge your spirit, Momus, and seize upon what you do not understand. Yet before long it will happen that you will weep for what you now laugh at. For you will too late experience the truth of the Greek proverb:

ῥᾶον μωμεῖσθαι ἢ μιμεῖσθαι —

“It is easier to censure than to imitate.”

Preface

Candid reader, behold again a new champion. I was lately persuaded to descend into this arena. I confess I never intended to seek fame under the banner of the pen, since for a long time chymical writers have had a bad name and are taken as synonyms for impostors. Whether this happens justly or unjustly, let the prudent judge.

The cause of this reproach seems to be the following: many proceed thus. When, after some years, exhausted in purse and health, they have drained all the windings of their brain and now hold only emptiness everywhere, lest they lose also the reputation acquired by long labor, they seize the pen and throw upon paper their specious processes, setting obstacles before everyone so that their writings may not be despised but gain weight through obscurity. And though some small profit may sometimes arise from this, yet they prefer to guard their reputation and to be held as such men as they are not, with great injury to conscience, rather than confess errors or remain silent.

Perhaps they conclude thus: “If I carry nothing else away from my furnaces, yet the title of learned and eloquent man will remain to me; who knows how it may profit me, even if not in this province?” As the poet says:

Semper tibi pendeat hamus, quo minime credis gurgite, piscis erit.

(“Ever let your hook hang: where you least expect it, in that pool there will be the fish.”)

But I, from youth up, few of words, in progress noting the sinister omen of scholastic talkativeness, found it for the most part bereft of real demonstration, poorer than Codrus. So rejecting it, I resolved to hunt the thing itself rather than words. Nor, God favoring, did success fail me. For I would not give my real science for all the rhetorical and logical treasure. I praise both, but I do not compare them.

In this literary tempest I see many sailing without oars, driven only by the wind of opinion, few knowing whither they tend, but like pirates wandering under uncertain elevation, gaining for themselves, by this foolish practice, some reputation for nautical science.

Therefore, lest they sell too many mists to credulous youth and lest, by the multitude of their lies, they entirely wrest our physical truth from the memory of mortals, I was at last moved to be for sale—not that I might seek vain glory from this cake, but that I might lead the erring amid so many myriads of writers into the straight path and guard him from the rocks of shipwreck.

I doubted long whether I should wish to throw myself among so many triflers and endure vulgar judgment. But the love of the neighbor who seeks prevailed. For what pleased me will not displease others. It is surely to be lamented that tailors, shoemakers, and cobblers are far more honest than most of our writers, for they keep what they promise, and for this deserve honor. But these think they have satisfied their office if elegantly, tersely, and cunningly they publish many volumes in print. Whether what they write is true or false, they consider to belong not to them, but to the common people, to bind themselves by words and stand to promises, as if noble dignity had its origin in the mire of lies.

Some even swear by the whole heavenly order, and if you judge otherwise, devote you to the lowest hell. But truly, how shamefully I and others have been deceived by these most wicked man-shaped beasts is not for this place, for it would make a volume, not a tract. It is the most foolish thing, and besides an inexcusable crime, to write words without the thing, and knowingly impose upon posterity. For the love of God, what are you thinking? Christians, if the supreme Judge requires an account of every idle word, what will become of you who sell to posterity whole volumes without the thing, and deprive the sweetest pledges of love—age, health, money, honor, and life?

Who among us does not lament about this or that author, that he was led astray by him for many years? How often do I exclaim: “O, if Jupiter would restore to me my past years!” Not that I wasted them in Venus and Bacchus, but that through many vain labors drawn from those cursed books, I destroyed both time and health.

But what presses you, spitters of books, that you cannot keep silence, if you wish to pour out nothing but words, which do not satisfy the heart? Surely ambition alone strangles you and makes you roar. Otherwise nothing. Of you is true the German proverb: viel Geschrey und wenig Wolle — “much cry and little wool.”

Chapter 1.

The Title is Proved.

It is clear in the open, nor will it easily be denied, except by one who is plainly ignorant of natural things, that to draw forth the one natural truth from the well of Hippocrates requires more wit, strength, labor, and time than to drink dry the very fountain of Hippocrene with all of rhetorical philosophy. For this latter, being born from the institution, law, and observation of men, is learned in comfortable leisure; but the former owes its birth to Nature herself, to the invisible spirit, to the Vicar of the Almighty God, and furthermore is so pressed down in the dark night of Orpheus, that if it should at any time be compelled to come forth into the light, it requires not one Hercules but the very tamer of the world, the element of Fire, with its dreadful torture. Indeed, even so it does not easily appear, unless the command of Him intervenes, before whom the mountains split and the abyss rises.

If we wished to deal in examples, the greatest abundance of them could be supplied from every age: men who, in every possible way and with all skill, sought naked Diana without her garment, through rocks and through fire; but either they did not find her, or, having found her, failed to recognize her with their deer-like understanding, and were made prey to their own hounds of industry. Widows and orphans in many places even now lament the prodigious prodigality of husbands and parents, squandered upon Alchymical matters without profit, except that in place of the Stone they brought back only a pebble, and in place of the Tincture only trembling and paralytic limbs. Yet it does not follow from this, that what the Alchemists seek is an empty nut, a dream, or Plato’s imaginary Republic. For Natural Truth is troubled, and moreover a chaste Virgin, not a prostituted hireling available to all.

Let the foolish have what they cling to in pitch. Let the Seplastae curse themselves, who, leaving the medicine of men, thought to contrive a clyster for metals far firmer, and misapplied their art. What has our Queen to do with bathkeepers and the company of courtesans? Not therefore does the goldsmith know the principles of metals because he has learned how to skillfully shape metals and gold itself. What familiarity have rustics with this our Princess, who inhabits fortified places and a citadel enclosed by a triple wall?

Finally, friendly reader, do you think that this heavenly offspring is without the care and love of her Father, so that any wanton goat, neglecting the Parent’s consent, might snatch her into his bedchamber and violate her? By no means of any nation. Rather, lest this should happen, she has been withdrawn from mortal eyes and entrusted to the Earth, the daughter of Jupiter, and buried in her bosom. She does not lie upon soft pillows, nor shine with garments purple and embroidered with gold, nor wander through pleasant willows and delightful fields to be gazed upon, nor is she to be gazed upon as she is, much less does she lead dances or seek suitors in the manner of maidens. Instead, with a certain royal nobility she prefers to hide within rocky arms and Cimmerian darkness, than to be kissed under soft plumes by the unworthy. Such until now has our Titonia been, and such she will remain until the age is burned into ashes.

Chapter 2.

The Causes are Suggested.

There is a common saying that the companions of Nature are for the most part atheists. This, without distinction, is plainly false and a monstrous lie. But the following proverb of the ancient Magi is true and indeed most true, where they say: “Our art either finds the good, or makes the good.” I admit willingly, and daily experience shows, that very many lovers of the art of Chrysopoeia live as Bacchanalians throughout the whole year, and are sparing worshippers of God. But I also add this: that in my judgment, and in the judgment of all who think rightly, those very pseudosophers are as far from the Golden Fleece as heaven is from earth, east from west, and white from black. Indeed I dare assert that such an adept never lived, and that the “impious wise man” (sapiens impius) is truly but an iron-wood, Sydiroxylon. This at least is true: impiety, especially when joined with filthy lust and greed, is an inseparable sign of an impostor and an ignorant man.

For the most wise searcher of hearts has never granted to anyone the keys to the fountain of life, except to him whom He foresaw to be worthy of life. Let those therefore who magnify such Satyrs and rational beasts, on account of their supposed knowledge, take heed, lest they vainly expect grapes from a thornbush, or figs from thistles.

The principal cause of the burial of our Hermetic truth is God the Best and Greatest, the Parent of all secrets. Since He is incomprehensible to the carnal eye, He has also hidden His treasures from it. Friends indeed can accomplish something, but not without the direction of the supreme Protosophus through the means of the agent. And if at any time it happens, through political trickery, that such a swine is led to the venerable temple of Nature, yet he neither perceives nor accomplishes anything, being blinded and hindered in various ways by the just judgment of God.

The second cause of this concealment are the Adepts themselves. For man, as such, scarcely lacks envy, especially in great matters, as may be seen in the high priest of our art, Hermes. For what is more obscure than his Tabula Smaragdina? Sooner will a three-formed Pegasus release you from a Chimera, than Oedipus solve this labyrinthine riddle.

In his footsteps faithfully followed Geber, Raymond Lull, Arnoldus de Villanova, and others. The Arab, as one endowed with a more enlightened wit and weightier judgment, set forth his doctrines more distinctly and dogmatically, yet almost everywhere withholding or cutting off the very point upon which the whole dispute rests.

Lullius, a man of subtle and crafty genius, perfectly palmed off his fraud upon the world. He noted, indeed, that the Latin Schools, led astray by the Greeks, held as the highest peak of wisdom the ability to speak promptly, sharply, and elegantly. Therefore, searching out every corner of Logic and Rhetoric, he clothed, obscured, and plainly buried his truth, as his contradictory and tautological writings abundantly testify. Yet at that time he pleased the learned world exceedingly.

Arnoldus de Villanova aimed at a similar praise, though he loved rather a Laconic obscurity than a fraudulent verbosity, and wrote his Rosarium Spinosum, in the explanation of which even Apollo would grow weary. And granted that Pyrotechnia may have gained some benefit from their writings in past centuries, all this was again overturned by the new doctrine of Count Bernard of Treviso, who proceeded by a method plainly different from that of the ancients.

For the earlier Sages recommended to posterity the simple homogeneity of Mercury. But he, rejecting this, introduced his “duplicated Mercury” upon the stage, with such constant and loud applause, that not even one of the Masters, so far as I know, ever doubted the greater excellence of it. Rather all with one voice adored this man as a Delphic Oracle, and subscribing to one another, thought that Nature proceeds according to the law of Arithmetic, and that the double is to be preferred to the simple. Whether this was rightly done will be shown in the following. Let it be noted here only, that a singular Spirit of Confusion, sent from on high to mortals, introduced this diversity, lest the human intellect, being always intent upon one thing, should at length, by penetrating, snatch the club from Hercules and mingle the highest with the lowest.

For the comic play of this amphitheater would be ended, if men indiscriminately possessed riches and health, and it would become purely tragic; for no one, unless overpowered by force, would serve another, and unspeakable crimes would be devised by the Devil in his members to the contempt of the Creator. For the whole world, lying in wickedness, promises nothing good any longer; vices have risen in the place of virtue. Flatterers, fools, boastful babblers, and cunning impostors ride in carriages; but the prudent, and those whose hearts Titan fashioned from better clay, go on foot.

Therefore our predecessors are not so much to be blamed, that they were faithful secretaries of Nature. Without this, the transmutatory art would daily prevail ethically, not physically. Everywhere almost gold is turned into lead—that is, golden tranquillity, charity, equity, and truth are destroyed by the cold fire of envy, and transmuted into the leaden dross of infernal iniquities. What, I ask, would happen, if also that other physical metamorphosis were made a matter of public right? Would not the world be devastated by mutual slaughter?

Behold, these are the impelling reasons of the tumult of our physical truth—certainly weighty ones, and such as are able to extinguish all love of the Adepts toward the human race.

Nevertheless, even if posterity, branding me with the same black mark as the other authors, should mock me, I will keep my promise. I will break open the marble posts of our tomb and open the barred door—yet so that not every child of Fortune, without wit and labor, may be able to drag forth and subject to himself this beautiful Goddess. It is enough if, to the learned, and to those whom many sleepless nights and watchful labors have consumed, I, as a faithful matchmaker, bring the desired Bride. But to novices I preserve both health and intact purses, and I show the way to this opened sepulchre, and carry before them the torch.

Chapter 3.

He Explains the Way.

In order that we may more easily reach the appointed goal, it will be absolutely necessary to cut down and clear away the brambles and thorns growing along the path, lest the traveler following after be wounded by their sharp spines, or be compelled altogether to stop. Yet steep rocks and dizzy precipices will still remain, which will strike terror even into the veteran soldier. For as many as ever wrote concerning the mysteries of nature, all mingled with their teaching various trifles, in order to ward off the profane from the true sense and understanding of the heart. Among these bastard sons of nature, Theophrastus Paracelsus seems to hold the chief place—a man of scanty literature, yet of great talent in more secret philosophy. For he often contradicts himself, and what he commends in one place, he condemns in another.

For example, in Chap. 7 of De Transmutatione Metallorum, he calls the matter of the Philosopher’s Stone “animal, vegetable, and mineral.” A little later, however, he rejects all minerals, saying that although the philosophers called their Stone “mineral,” they did not wish the matter of it to be sought from any of the minerals. But in Chap. 11 of the same treatise, he presently commends the immature mineral element as the undoubted true matter. At one moment again he rejects the vulgar Mercury; at another he proposes it, as may be seen in this treatise and in Book 10 of the Archidoxes. Elsewhere he extols his Saturn to heaven; elsewhere he condemns it, while passing over in silence the labors to be sought in sulphur and vitriol of the vulgar. Which indeed is nothing else than to bewilder the world and to sow tares among the wheat.

If the matter of the Philosopher’s Stone is not threefold in the literal but in the mystical sense, then it follows that it is mineral or metallic in the proper meaning, and that the only distinction is between the remote matter and the proximate matter; for in the mineral the metal can very well lie hidden. Now he who knows how to distinguish between the moist way and the dry way, between the matter in qua and the matter ex qua, such a one may read his writings without danger. From either of these a homogeneous Mercury is drawn forth, whether it has been reduced to a moist or to a dry form—it is the same; the only requirement is homogeneity and the matter in qua, which is altogether different.

If you follow in the footsteps of Paracelsus and choose the moist way, you must first provide yourself with the immature mineral Electrum, which is difficult to obtain, and then proceed philosophically, that you may take the glue of the eagle’s claw pure and shining, as he teaches in Chap. 14 of De Transmutationibus. And he indicates the place, saying: “Better instruments you will not find than in Hungary and Istria.” In short, Paracelsus possessed four arcanum menstruums, by means of which he accomplished whatever is reported of him. Namely: the greater and the lesser Sal circulatum, the liquor Alkahest, and the Mercurius Philosophorum in liquid form.

The Sal circulatum maius is made from common salt; the lesser from salt of tartar. The liquor Alkahest is made from Mercury; the Mercurius Philosophorum in liquid form from the mineral Electrum, or ♄ (Saturnus Philosophorum). The difference between the last two consists only in this: that the Alkahest is simpler than the Sophic Mercury, which with good reason can be called “duplicated.” If you seek the medicine that cures metals, leave the three former aside, and pursue this mineral. In this you will, in short time and without excessive labor, find that by which this Helvetian boasts. The further process to the Tincture was for the most part delineated by Brother Basilius Valentinus.

Here you have the kernel of Paracelsus’ writings; turn this into juice and blood, and consign the remaining mass of paper to the moths. But you object: “Teach the method which Paracelsus omitted.” I reply: the two former he taught at sufficient length himself in Book 10 of the Archidoxes. As to the latter, I say: reduce the vulgar Mercury to homogeneity by removal of its earthiness and superfluous inequality, and then turn it into water by solution with its mother, or with the stomach of the ostrich, and then you will see why Helmont said in his treatise Arbor Vitae that for preparing the Adept’s doubled liquor Alkahest the Tree of Life is required—and you will thank me.

As for Raymond Lull, I advise the beginner to leave him entirely. He is too prolix, thorny, and mendacious. The truth which he concealed under the obscurities of words and a vicious circular style you will obtain much more clearly and quickly from Geber. For he defends the same opinion with him, and acknowledges for his object the simple homogeneous Mercury. But Geber’s particular processes, beyond Homogeneity of ☿ (Mercury), are mere shells without a kernel, and mussels fit only for the unworthy.

Arnoldus de Villanova sings nearly the same song with Lullius. Leave his preparations of vulgar ☿ Mercury by sublimation with saline bodies, and his revivifications of the same by quicklime and resuscitative salts. For never in this way will you whiten the Ethiopian. I briefly pass over these authors, partly because their frauds have already been exposed by others to modern operators, and partly because in themselves they are not so very subtle, unless someone wishes to be excessively ταχυπεϑης (rashly hasty), and, neglecting faithful admonitions, to be wise in his own experience together with the Phrygians.

Among canonical modern authors, after Bernard, the most famous are Sendivogius and the most recent anonymous Philalethes. Although both were Adepts in fact, yet they differ astonishingly from the doctrine of the ancients, so that of them, as regards fundamental knowledge of natural things, it may truly be said that they thought a mouse sprinkled with flour to be the master of the mill. Yet among these, Bernard was a man of more solid doctrine and experience. For although he was the first to make mention of his duplicated ☿ Mercury before conjunction with perfect bodies, yet he did not totally reject simple Homogeneity (in respect to his hypothesis), but in his Epistle, Obsequia, etc., he commends both sublimations of ☿ Mercury—by those bodies with which it does not agree, and by those with which it has affinity; but he prefers the latter, with what reason will be said in the following.

That Polish writer Sendivogius, and the most recent Philalethes, both Adepts by communication, attempted to overthrow the whole edifice of the wisdom of the ancients. They constantly and expressly—especially the latter—deny that the Homogeneous ☿ Mercury of the Sages can be fabricated in any other way than by amalgamation with the martial regulus of iron, stellatus. But how miserably they are deceived, and deceive others, I shall briefly prove mechanically, since in natural things a real demonstration is stronger than any syllogism.

It is clear that Sendivogius persists in the same opinion as Philalethes, and that the latter only explains the former, from various places in his most obscure treatise. For after he had, for the greater confusion of the reader, in his twelve treatises and their epilogue, most copiously extolled false substances, not metallic, he then slides into subsequent enigmas regarding that Regulus Martialis, which he afterwards repeats in the Dialogus cap. Physici, but most clearly in the treatise De Sulphure at the end, where he says: “Salt and sulphur circled around a well, quarreling with one another, until at last they came to blows and fought, in which conflict salt inflicted upon sulphur a horrible wound, from which, instead of blood, milk flowed,” etc. Who does not here see depicted the doves of Diana of Philalethes, and his whole process? It is so.

Let us come to Philalethes himself. He, not departing even a nail’s breadth from the manner of writing of the other Adepts, says: “This and many other ways is the ☿ Mercury of the Sages prepared.” As if indeed he had just visited all the innermost secrets of Nature, little remembering that he became possessor of his Mastery not by analysis and practical knowledge of natural things, but either by theft, as some wish to think, or by the communication of another, and that indeed in the twenty-third year of his age. For I ask all the Philosophers by fire: what familiarity and love could such a youth have contracted with our venerable Matron, Nature? Surely little.

Since, however, his treatise is in almost everyone’s hands, it will also be known that the foundation of his ☿ Mercury Sophicus is the martial fire communicated by fusion with Regulus Antimonii, which must then be joined radically with vulgar ☿ Mercury, so that the ☿ Mercury of Antimony (♁), animated, may couple with vulgar ☿ Mercury, and each may cast away its scoriae. The practice undoubtedly succeeds, provided the intermediate, or the doves of Diana, are present. But that the cause of the purgation of vulgar ☿ Mercury is the martial fire, insinuated into it by the Antimonial ☿ Mercury (♁) hidden in the Regulus, and that there is no other way—this is what I deny, and deny utterly, being led by the following arguments and mechanical demonstrations.

First: it is false that the ☿ Mercury of Mars (♂), in fusion, is mixed with the ☿ Mercury of Antimony (♁) in the Regulus. Yet this he boldly asserts in several places, and very clearly in Chap. 2 of the Introitus Apertus, with these words: “For our Dragon, which conquers all things, is penetrated by the odor of the Saturnine vegetable, whose blood together with the juice of Saturnia coalesces into a marvelous body, which, however, is still volatile,” etc. Here indeed, without contradiction, he asserts that the best part of the metal, namely the Mercury of iron, in the fusion, is joined with the ♁ Antimony. But by the following mechanical demonstration this is found to be false:

Book 1. Melt ♁ Antimony in a crucible. Into the molten mass thrust a piece of steel, extremely heated and glowing. You will see the ebullition of the mass and the liquefaction of the iron. When this ceases, at once add another piece well-heated in the same manner, until the steel is no longer attacked by the ♁ Antimony. This seen, immediately with the greatest fire melt the whole matter anew, and when it flows well, pour it into a hot casting-dish well anointed, shaking the brass so that the Regulus may descend the better. From the cooled matter separate the Regulus, and a third time purify it with nitre and tartar, and weigh it—you will have about eight loth.

Now also make the Regulus with equal parts of Antimony, Nitre, and Tartar, in the common way by ignition in a large mortar; melt the remaining matter, shake the casting-dish industriously with a quick hand and strong fire, that the Regulus may be well precipitated from the scoriae, and you will obtain the same weight, if you have operated well.

Pulverize the scoriae of Mars (♂), and on the test, with gentle charcoal fire, drive off the ♁ Antimony. There will remain an iron powder, almost of the original weight, retaining all the properties of iron calcined by common sulphur. It dissolves in acid liquors, and yields a beautiful vitriol—which would not be, if the iron were deprived of its ☿ Mercury, as all sounder philosophers will admit. If now the ☿ Mercury of Mars (♂), its golden soul, had been joined with the ☿ Mercury of Antimony (♁) in the Regulus, then the following would result:

1. That with Mars (♂) more Regulus would be produced than with salts—which is false.

2. That the iron remaining in the scoriae would be diminished at least by a fourth part—which likewise fails.

3. That with the simple Regulus, vulgar ☿ Mercury could not be purged—which again is erroneous. For there is no difference between the two, not even in regard to the star. For I have often seen a simple Regulus most beautifully stellated, and myself, more than ten years ago, prepared such a stellated Regulus, sometimes adorned with yellow stars, sometimes with white, according to the season, with more or fewer stars, by the abundance of salts. And I still daily dare to demonstrate the truth of this assertion. Nor will anyone easily err in this, provided only that he add a sufficient quantity of salts, and melt at the due time. Otherwise, also, the Regulus of Mars (♂) will lack its adornment, though melted a hundred times; for the time for contracting the star is not any time, but a definite one. For everywhere the motions of Nature are μεσοι μενοι καὶ τεταγμενοι—“measured and appointed”—and require a fixed aspect of the heavens.

Furthermore, if the martial fire of Mars (♂), hidden in the ☿ Mercury of iron, is the cause of the purgation of vulgar ☿ Mercury, as Philalethes asserts, and if he proclaims that from this his ☿ Mercury Sophicus emerges, plainly impregnated with an internal spiritual sulphur, then why does the ☿ Mercury of Antimony (♁), extracted from the Regulus of Mars (♂), not accomplish the same, since I have seen that it lacks this virtue?

It is indeed true that perfect bodies, and their internal good sulphurs, or souls, purify vulgar ☿ Mercury by the illumination of the mercurial center, itself pure and homogeneous, so that then the external arsenical sulphurs are despised and cast out as hostile. But that same purgation is not denied even to metallic arsenical sulphurs, by right of similarity and self-love, although they cannot breathe in the golden soul, but only seize upon what is of their own kind.

Therefore the true cause of the purgation of ☿ Mercury, by amalgamations of the Regulus, is not that solar fire which in its ☿ Mercury duplicatus does not in the least reside, but rather the abundance of arsenical sulphur in the Regulus itself. This, by means of the artifice of the doves, is loosened from its chains, and by a certain natural necessity seizes upon its like in vulgar ☿ Mercury, leaving behind a third thing. For what happens with ♂ Mars and ♁ Antimony, the same also happens with the Regulus and ☿ Mercury, an intervening artifice being employed. When sulphureous ♂ Mars seizes upon sulphureous ♁ Antimony, then the ☿ Mercury of Antimony (♁), which is not bound as is the Martial, falls to the bottom. Yet by this means it cannot be entirely freed from its keepers, but retains about a tenth part of its arsenical sulphur. This then, once disposed and prepared, again seizes upon its like in vulgar ☿ Mercury, and so finally leaves behind its own ☿ Mercury as something dissimilar. The same may be seen also in the purification of other metallic ores; for example, smelters, when lead ore is arsenical or abounds in other sulphur, add iron ore and obtain more metal, etc.

But granting that some golden virtue exists in the reguline ☿ Mercury, which might animate vulgar ☿ Mercury, why does it not do so to its dearest companion, the ☿ Mercury of ♁ Antimony? Why is vulgar ☿ Mercury required in order to exert this energy? You object that this cannot be done in one operation, on account of the multitude of diverse sulphurs in ♁ Antimony. I answer: let it pass that its purgation is not completed the first time; let a second addition be made, the Regulus having been already formed, and so at length it will suffice. But even so it does not succeed—not because the ☿ Mercury of ♁ Antimony in the Regulus is sufficiently purged, but because it now lacks the sulphur, that common combustible which dissolves iron. I prove this by another mechanical experiment. Extract the combustible sulphur of ♁ Antimony from crude ♁ Antimony, in such wise that the sulphur extracted is as like to vulgar sulphur as one egg is to another, and the ♁ Antimony retains its external form as before, except that it no longer scintillates as before. Melt this ♁ Antimony, and plunge into it glowing iron, as if you intended to prepare martial Regulus, and you will see that the operation does not succeed, and the iron remains untouched. The reason is that the ♁ Antimony is deprived of its combustible sulphur, by which ♂ Mars is dissolved.

Further, you insist that this golden power in ♂ Mars is a mere spiritual vapor, as the same Philalethes in his Biorhium and elsewhere fables. But I ask: what is the reason why this wandering fire, since it is spiritual and not bound to the Martial ☿ Mercury, is not expelled by the fire of fusion and by repeated ignition in the furnaces, but only awaits Jupiter (♃), and when he approaches abandons his old host, the ☿ Mercury of iron—who yet is far more noble than the Antimonial (♁)—and ungratefully seeks out and perfects a new one? Again: why should this spirit of gold lie hidden only in iron, the house of Aries, without a body of gold, and not also in copper, since with ♀ Venus, by equal preparation and method, a most beautiful Regulus is prepared? Yet everywhere the vulgar cry of the Chymists resounds, that ♀ Venus abounds with golden sulphur, and that the copper roofs themselves are finally cooked by the Sun into the Sun.

You reply: that Philalethes expressly denies this in Chap. 11, namely, that the Philosophers sought in vain in ♀ Venus. I rejoin: that Philalethes was here deceived, as is clear from what has been said. For it does not follow: “I know some supreme secret by communication, therefore I know all of Nature.” The knowledge of the whole of Nature must be sought from mere species and individuals, nor is this good man everywhere present to himself. For after he had denied to vulgar ☿ Mercury and to simple ♁ Antimony an active sulphur with many words, in Chap. 11 he finally says that vulgar Mercury has within itself a fermental sulphur (that is, an active one), of which even the least grain coagulates its whole body—provided only its heterogeneous impurities are removed. Which indeed is true, but contrary to the hypothesis of Philalethes.

From these things I think it abundantly clear that the theory of this Adept is verminous, though his practice walks with a straight step. For it is not absurd to know the essence of a thing and yet not to know the method. Nay, this is almost ordinary with great and small, with the learned and the unlearned alike—to embrace the thing itself, and not inquire how it exists. From this source of negligence flow very many evils, which make the world full of error and a valley of miseries.

Chapter 4.

He Teaches What the Mercury of the Sages Is in General.

I hesitated for a long time whether I ought to repeat the same matter again, and, as it were, to serve up the same cabbage boiled over to nausea in these philosophical banquets, since scarcely any of the ancient or recent authors are silent on this subject. Indeed, even those who have not so much as rightly greeted this Wisdom at the threshold, but, like jackdaws, have adorned themselves with borrowed feathers, chatter and clamor enormously about this material—opening their beaks wide like geese among swans. For they do not know how to come closer to this fire; therefore, from a distance they admire its incomparable splendor, and at street corners and crossroads they proclaim it with such loud cries, as if the valleys and mountains themselves were their hearers.

The proverb among the ancients was to say of a common matter: “it is known to the blear-eyed and to barbers.” Yet the emphasis of this saying is far too narrow for our application; for in this age many rustic illiterates and unlearned women at the plough and the yoke know fundamentally and in general how to dispute about this ☿ Mercury of the Sages. But in truth, just as Helmont rightly divided brute animals δυστυφως, into Solarians, which by benefit of the Sun see by day, and Lunarians, which by means of the Moon see by night and under the earth—so, notwithstanding this very clear and most commonly published knowledge of the ☿ Mercury of the Sages in general, yet there are to be found the purblind, who, like bats, either hate or cannot comprehend this light of truth, and hurl others with themselves into their gloomy abyss.

It would be pardonable if shoemakers gave unjust judgments beyond their shoe. But that such sophists should inscribe themselves with the certain and rightful titles of promoted Doctors, and even flatter themselves as actual Adepts, such as Philalethes, under this specious designation, accuse others of falsehood, and deceive the world—this cannot be winked at. Rather, effort must be made so that men of sound heart and ingenuous mind may be fortified against such a plague, and, if possible, that the very square intellect of such a foolish Doctor may be circumcised and reduced to a more fitting form for conceiving the ☿ Mercury of the Sages. For it cannot be denied that Helmont, among the sounder philosophers easily the greatest, determined that for a true act of understanding it is required that the intellect become, as it were, one with the thing understood, and be in some way transmuted into it.

That the weakness, if not stupidity, of their mind may more clearly appear to all the ministers of our Queen, let us set up the two supports of the whole building of Nature: Reason and Experience. And let us repudiate any structure that does not rest on these as unarchitectonic. Let us briefly survey the three kingdoms of Nature, presupposing, from the most ancient and orthodox writer of natural things, Moses, that every living body has received from the Creator the power of multiplying itself by gift of creation.

In the animal kingdom, perfect animals multiply themselves by the mingling of seeds, each in its own kind and species. Worms, however, which arise from putrefaction through something analogous to seed, nevertheless require prepared matter for their anomalous generation. Thus worms born under rotting wood differ from those that arise in decaying flesh. For not everything comes from everything; but always some generic preexistence of matter is required—in perfect animals very strictly, in imperfect ones more loosely. In these latter, the potency of ferments supplies the place of specific matter, which is not the case in the former. Therefore also the life of imperfect animals is short, owing to the inadequacy of their principles.

The generation of these is more distant from the cradles of metals than a carbuncle is from flint. Let us therefore leave it, and hasten to the lineage of vegetables.

The proximate generic matter of all plants is the woody juice. All plants whatsoever multiply themselves by means of their seed, as by a feminine principle. Proofs of this we omit for brevity’s sake.

In the mineral–metallic kingdom the proximate generic matter is a mercurial, ponderous, and homogeneous substance. The difference of these three kingdoms lies in this: among perfect animals, because of the diversity and multitude of noble organs, the tribute of male and female is required. In vegetables and minerals a sulphureous fermental odor suffices, supplying the place of the seminal Archeus, the material or feminine principle meanwhile being rightly disposed.

Of the feminine principle in the first two kingdoms none doubts; but the last may be called into question by the unlearned. Wherefore it is necessary to call upon the authorities of the ancient Adepts, since in the hidden caverns of the earth the marriages of this kingdom are for the most part celebrated.

Yet sound reason also urges incorruptibly, that everything consists materially of that into which it is resolved by a fitting regression. But all metals are resolved into ☿ Mercury: therefore from it they consist. This all the ancient philosophers confirm.

Let Arnold be first, who in Chap. 2 of the Rosarium says: “It is certain that everything is of that, and from that, into which it is resolved; for when ice is changed into water by heat, it is clear that it was formerly water. Likewise, in Chap. 2 of the Rosarium: from argent-vive all metals are, and into it they are resolved.”

Again in Chap. 1 of De Natura Rerum: “Nature forms all metals naturally, by her operation, from argent-vive and the substance of its sulphur, since it is proper to argent-vive to be coagulated by the heat or vapor of sulphur.”

Nor is the Prince of the Alchemists, Geber, contrary, in Chap. 3 and 9 of his Summa. For there he plainly indicates in many ways that the principles of metals, upon which Nature founds her action, are argent-vive, sulphur, and its companion Arsenic.

That by this ☿ Mercury the Philosophers understand that metallic fluxible substance, both with and without philosophical preparation, is clear. First, from Arnold, Chap. 4 of the Rosarium, with whom Geber agrees, Book 2, Chap. 8, where he says: “Let the Almighty Maker, the glorious God, be praised! who from the vile created the precious, and gave it a substance and the property of substance, which no other thing in nature happens to possess, because it alone is that which overcomes fire and is not overcome by it. For it alone, being a metal, contains in itself all that we need for our magistery; because all other things, being combustible, yield to fire and perish in the flame.” Likewise, in Chap. 2 of the Rosarium: “Argent-vive (☿ Mercury) contains within itself its good sulphur, by means of which it is coagulated into ☉ Sol and ☽ Luna.”

Bernard also agrees in his Epistola Obsequiis, expressly saying: “The dissolver differs not from the dissolved, except in digestion and maturity. Therefore it is metallic.” And further in the same he says: “No water naturally reduces and dissolves metal, except argent-vive (☿ Mercury).”

Also: “The natural solution of metals can be effected by no other thing, nor is it expedient, except by argent-vive alone. Therefore crude ☿ Mercury is joined, as water, with the body by the spirit, in order that by the first decoction it may be dissolved.” And he further says: “Every doctrine is false which alters ☿ Mercury before the conjunction of the body with it. Therefore it must remain in its metallic fluxibility. Which he afterwards also expressly teaches there, saying: It is not to be doubted, but that ☿ Mercury can and ought to be sublimed by common salt, so that the scoria mineral extrinsically adhering may be removed; yet always with the ☿ Mercury flux, or radical humidity, remaining, that is, its mercuriality standing incorrupt, which is from its natural proportion. For the mercurial species and form must remain incorrupt in our work.”

What could be clearer? For this reason also he commends his sublimation by amalgamation with Regulus Antimonialis, saying: “There are certain sublimations of ☿ Mercury from its proper bodies, which, by intimate amalgamation, are joined and mingled with it; from which, being often raised and reunited, it casts away its superfluities, and is not confused in its nature. Therefore afterwards, by this art, it avails truly in melting or dissolving metallic species, nor is it intrinsically much altered for our work, except by fixed bodies dissolved in it.”

You object: 1. That here the matter of the metals is confounded with the Philosophical ☿ Mercury. I reply: it is one and the same. 2. That the Philosophers mean not the vulgar ☿ Mercury. I reply: you infer rightly, but you conclude wrongly. It does not follow: “The Philosophers reject vulgar ☿ Mercury; therefore they commend nitre, virgin earth, salts of every kind, and other refuse outside the metallic genus.” What then?

Let vulgar ☿ Mercury be the matter ex qua, as Philalethes himself candidly admits; yet it will not therefore be the matter in qua. Do you think, if Hermes or any Adept you honor were to be revived, and were to reveal to you, as by divine voice, that vulgar ☿ Mercury is the true matter ex qua the Sophic one must be prepared, that you would at once be so learned and qualified as to accomplish this mystery with unwashed hands? By no means.

For this operation is so hidden and inscrutable, that even if one should most perfectly teach it to you, and place in your hands all the requisites, yet you would not on that account achieve triumph, but, as the Philosophers say, you would leave off the work where you ought to begin.

It is not a vulgar art of chemistry, nor one learned in idle leisure. If the Philosophers had not known the difficulty of this practice, they would not have written so clearly. Hear what Geber says, Chap. 45 of the Summa: “Mercury (☿) must be well purged, that it may become most white; for such as the purgation is, such also will be the perfection attained in projection. Therefore, if you have purified and perfected it by subtiliation, it will be a tincture of whiteness, to which none is equal.”

What, then, is to be purged? The same Geber teaches, Book 2, Chap. 9: “There is a twofold sulphureity and humidity in argent-vive: one which is enclosed in its center from the beginning of its mixture; the other, supervenient, alien to its nature and corruptible. The first can by no device of art be taken away, because it belongs to the perfection of the body, and this sulphur protects argent-vive from burning. But the other, though with labor, can scarcely be removed.”

Again, the same, Book 2, Chap. 37: “The highest intent of the whole operation is that the Stone, known from the preceding chapters, be taken, and with constant diligence the work of subtiliation of the first grade be carried out, and that thereby it may be purified from corrupt impurity.”

Nevertheless, in spite of these most clear doctrinal statements, Geber yet very truly says, at the end of Chap. 32, that “this art does not come to the craftsman of stiff neck.” The same is affirmed by Arnold, Chap. 2 of the Rosarium. Therefore, dearest Philochymist! although you may be envious, yet nevertheless be of good courage, and do not fear the publication of this mystery; for I swear to you by the immortal God, that scarcely one out of a thousand attains his intention, even though he know the subject perfectly. But if you indeed breathe lofty things and disdain the vulgar, be also glad: for by this practice you will have the best occasion of showing the nobility of your genius. Nothing here is trivial, nothing common will occur. If you desire that which is dearly bought by much labor, here is the stable of Augeas—if you are a Hercules. For most certainly you will experience that verse:

Non venit ex molli veneranda scientia lecto.

(“Venerable knowledge does not come from a soft bed.”)

If hidden things please you, do not despair, but seek diligently for many years, and at the end you will find that you discover nothing, unless either a friendly or divine hand has led you. If you love the simplicity of things, here is my hand: remain, I pray, in the simple way of Nature; for in this you will sooner grasp that which in subtilities you will never see, as Sendivogius testifies.

Therefore the generation and multiplication of all three kingdoms is made in their own kind and species. And although, because of defect of organs, in metallic propagation the conjunction of male and female does not take place so manifestly as in animals, yet it cannot be denied that there is an analogous commixture of the masculine and feminine seed. For the active elements, as it were the masculine seed, naturally join with the passive, as with the feminine, a due proportion of Nature being carefully observed. This first commixture is called the material digestion, in which from potency arises act, namely: from earth and water come air and fire, through pure digestion and subtiliation of them. Nor is there any other addition in the womb of the earth besides the digestion and inspissation of ☿ Mercury itself, as Geber philosophizes, and Bernard in his Commentary on Arnold.

From this foundation the ancient Magi discovered their ☿ Mercury, by following Nature, and to it, pure and homogeneous, they added likewise pure gold, and by degrees of heat they matured it—not that there is any other sulphur in ☉ Sol than ☿ Mercury, or in ☿ Mercury than ☿ Mercury itself; but because in the Sun there is a more perfect and more mature digestion than in ☿ Mercury. Wherefore the Artificer produces the work sooner than Nature. For gold is nothing else than ☿ Mercury digested and inspissated, homogeneous. Thus Art, by a compendium, joins gold with ☿ Mercury, from which two sperms is mystically generated in act that very same thing which Nature in minerals produced from one sperm.

But the way of this decoction and dissolution is open only to the rarest of men. And he who knows it, arrives at the secret, which is species permitiscere et naturas a naturis extrahere, as Arnold says, Chap. 1 and 2 of the Rosarium. Therefore the definition of the Sophic ☿ Mercury stands firm and unshaken by reason and experience, excluding all salts except one, which to it is as mother, and therefore tasteless. He who knows this sits in the center of Nature, nor will he be contrary to me: for he who is a friend to the mother will not be hostile to her son and his affections.

Rightly therefore you laugh, Philalethes, and many others, at those blind operators, who outside the metallic nature of ☿ Mercury waste their labor and oil upon salts, May-dew, rainwater, and suchlike trifles.

But the ancient axiom will remain true forever: In ☿ Mercurio est, quicquid quaerunt sapientes. Here, without doubt, they understand metallic ☿ Mercury, as the ancients inculcate to satiety, crying aloud.

So Ripley: “Join genus with genus, and species with species.”

Nature is increased in its own proper species and nature, and not in another.

And Bernard: “Our medicine is made from two things of one essence, that is, from the union of fixed and not-fixed ☿ Mercury, spiritual and corporeal.”

Also: “There is no profit in things not metallic.”

Also: “In, with, from, and through metals are metallic things made,” etc. And unless this vaunted Mercury of the Sages were to be sought from the metallic kingdom, Geber would have written in vain, Book 2, Chap. 2 of the Summa: “It is not possible to know the transmutations of bodies or of argent-vive itself, unless upon the mind of the artificer there come true knowledge of their nature according to their causes and roots.”

The same also there: “It is necessary that the artificer not be ignorant of the first principal roots, which belong to the essence of the work; for he who is ignorant of the beginning will not find the end.”

Therefore, unless one be plainly vertiginous and a grandson of Midas himself, he would easily perceive, with much and deep meditation,

1. that it is not granted to art to make a metal from a non-metal, as is also evident in the projection of the Stone itself, which, though it relies on the most powerful metallic ferments, nevertheless works only upon metals.

2. That every perfective action consists among similars. Which, being rightly attributed κατ’ ἐξοχὴν to the conjugal union of our ☉ Sol and ☽ Luna, will not only be useful but necessary because of the generic affinity.

He who asserts the contrary without reason and experience is no Philosopher, but an opinion-monger and impostor, plainly a “black one,” whom you, Roman, beware of—until he, from his savory salts, returns to our ἄποιον, the tasteless Salt of Nature, and adores it.

Of this alone is it true, what the Philosophers say: “In ☉ Sol and in the Salt of Nature are all things.”

It is, however, called Salt, not because it is made from any saline matter, but because outwardly it resembles nitre. I therefore conclude with our King Geber: “He who attempts to tinge without argent-vive (☿ Mercury), proceeds blindly to the practice, like an ass to a banquet.”

Chapter 5.

He Teaches More Specifically What the Mercury of the Sages Is, and Recounts Its Difference.

The mists now dispersed by the energy of the rays of Truth, it remains to explain more specifically what ☿ Mercury of the Philosophers is, and whether it admits a certain latitude significantly differing. When these have been premised, we shall subjoin the practice, so far as the plan of our treatise permits.

☿ Mercury of the Sages is, as has been said above, a metallic substance, either liquid or running, most pure and homogeneous, containing within itself a spiritual sulphur, by means of which it is coagulated.

It will seem erroneous to not a few, that this liquor should be declared double, moistening and not moistening, since many of the Sages have expressly indicated that it does not stain or wet the hands. But as not every soil bears everything, so not every age. The gifts of God have not shone upon mortals all at once.

That there are several ways, long known, leading to one goal, the prince of the Chymists, Geber, most acutely foresaw, if he did not know, in Book 1, Chap. 28 of his Summa.

Running ☿ Mercury of the Sages was taught by Geber, Arnold, Bernard, and, among the moderns, Philalethes. The liquid, moistening ☿ Mercury was possessed by Paracelsus, Basil Valentine, and in our time Agricola the Elder and the Younger.

Each of these ☿ Mercuries is legitimate and adorned with its metallic sulphur, by means of which it can be coagulated. They differ, however, in this:

That the more liquid is more general, the running is more special in relation to the metals.

The former is by far cooked into tincture by another fire than the latter.

The ultimate difference is in the virtue of tinging—complete in the second or third rotation.

Both are well known to me.

With what dexterity, and by what hand-guides, the business must be handled, I will briefly declare. Since art derives its work from the same matter upon the earth, from which Nature, under the earth, produces ☉ Sol and ☽ Luna, as Geber teaches, therefore before all else we must know the principles of Nature; for from these flow afterwards the principles of Art. Bernard affirms the same in his Commentary on Arnold, in these words: “He who wishes to attain to the intent must consider the principles and causes of metals, and how they are composed and united; then consequently, these being known, the work of solution and digestion will be easy. For it has been said how they are bound; but whatever is bound is soluble.”

These principles being known, Geber says, you will come cheaply to the completion of the work.

I am pleased therefore to adduce briefly the mode of generation of metals from Bacon, who says: “It happens in the earth that sulphur and ☿ Mercury are created, whose nature it is to be evaporated and sublimed by heat. The heat being kindled in the sulphureous earth, when for many years they have evaporated, both, ascending continuously through the earth, are coagulated on the way, and are struck back by the cold of the surrounding air; and hence metals are for the most part generated in mountainous places, as being colder.”

This generation Bernard sets forth much more clearly, as was noted in the preceding chapter, and it is here to be repeated. Nature in the womb of the earth works a metal from one sperm only, namely ☿ Mercury, by cooking and digesting. Therefore it cannot attain the determination of a metal in a short time; for in ☿ Mercury there are only two elements actually, namely water and earth, which are passive; fire and air are in it only potentially. But when they are brought into act, according to a determined digestion and proportionate inspissation, then it becomes metal. Nor is there any other addition in the womb of the earth, except the digestion and inspissation of ☿ Mercury itself; the difference depends only upon accidents.

Thus Nature from simple ☿ Mercury produces ☉ Sol, by removing its superfluities. But since these are of most difficult separation, therefore little gold is generated.

Therefore the whole artifice of the Sophic ☿ Mercury consists in the removal of the terrestrial and phlegmatic superfluities, as Geber teaches in Chap. 19. Argent-vive (☿) is not permitted to penetrate to the depth of an alterable body without a preparation intervening. For, as Geber says, Chap. 42: “It cannot be well found that it unites with bodies, unless it be spirit alone.” And a little after: “Because in many other things than spirits we see adherence to bodies with alteration, it was necessary to prepare them with purification, which is by subtiliation.” And in the same place further: “Because spirits projected upon bodies, without their purification, do not give perfect color, but wholly we see them corrupt, burn, and blacken.”

The practice of this preparation Geber teaches most clearly in several places, and it is by subtiliation—that is, the elevation of a dry thing by fire, with adherence to its vessel, and separation of the pure substance.

For ☿ Mercury contains in itself, as Geber also says in Chap. 42, the cause of corruption, namely: an earthy substance, combustible without inflammation, and a watery substance. These superfluities must be separated and it prepared. And this, as the same Geber teaches in Chap. 43 and 45, is done by fire and by the commixture of faeces, as is explained there at length and in detail. To these I remit the reader; for it is impossible to speak more clearly, unless one were willing to cast pearls before swine.

He who shall be diligent, learned, and constant, and who shall rightly invoke God, will find the truth in this Author. He is not to be compared with any of the ancients or moderns in candor and truth.

Through him you will behold, in the midst of darkness and the Stygian wave, our Proserpina, most splendid Goddess of riches. But beware the foul odor of the sepulchre. If you are prudent, you will easily imagine that so long and close a burial cannot be opened without dreadful stench. But rather, prepare the half-bath, and wash this royal offspring until she shines like the Moon in her fullness, and you will marvel that among so many filths and blackest scoriae this tender Princess has not been entirely suffocated and delivered over to eternal death.

You will now also observe why Geber, Chap. 26, Book 1 of his Summa, calls the principle of metals a “fetid spirit.” You will also know why our ancestors surrounded the caduceus of ☿ Mercury with serpents. For when this spirit is newly extracted from its absurd body, and most thoroughly washed, then it breathes forth an odor like that of serpents, if they be kept in a glass or ampulla, and it retains this odor until, with time, it exhales from the opened vessel.

Now also you will understand the philosophical axiom: Our ☿ Mercury is Mercury from ☿ Mercury, and Sulphur from Sulphur—which without this practice it is forbidden to grasp.

No one certainly, unless an eyewitness, can believe that in our foul fountain there is living water. Therefore I forbear to speak many words; he who has attained this arcanum, though I am silent, knows it; he who has not, will hardly be persuaded, even by Themistoclean eloquence. For it is customary for mortals to seek in the concavity of the Moon what lies before their feet.

You object: these things you set forth are theoretical. I reply: that is theoretical which is founded upon speculation without actual demonstration. But I, on the contrary, can practise these things as often as you request.

If, however, you delay belief until I turn a hundredweight of lead into gold before your eyes, then meanwhile recline upon leaden couches, lest by standing till the Greek Calends you put yourself to too much discomfort.

Whether you believe me or not, by me the heavens will not fall. The most wise Parent of things, from the foundation of the world, has hidden these gifts of His under the humble tamarisk, lest the lofty tops of the cedar, if they should obtain them, might altogether transcend the clouds, and rival the tower of Babel. I have written what I know, true things—not for the favor of the mighty, but of the wretched.

Chapter 6.

He Examines Particulars.

Nothing is more common or ulcerous to this age than deceit, amidst such prodigious abundance of most perverse men.

For he who has scarcely learned to kindle a fire straightway endeavors to persuade others that he is the possessor of this or that particulare worth thousands. I know by repeated experience, but never in my life—though I certainly have not passed it at the maternal hearth nor upon a cushion of idleness—among so many Particularists did I see even one who could have sustained a dog or a cat with this their fictitious gold. For it is impossible that there should be any particular in that sense in which the merchants of processes use the word, as if sulphur of ♁ Antimony and its tincture extracted from glass, or other sulphureous substances sought from ♀ Venus, ♂ Mars, and other minerals, through certain fixative fluxes and peculiar modes of ingress, could be intruded into ☽ Luna and tinge it.

The reason is, that such sulphureous substances can by no means be united with ☿ Mercury corporeal, intimately and radically, so that afterwards it would defend them in the fire of fusion. For this ☿ Mercury of Luna, without such addition, is coagulated by its own sulphur and by the degree of its own cooking, so that it does not need another, and such an inept, coagulant. And though it should have been made volatile, yet for sulphurs to unite radically with ☿ Mercuries without previous putrefaction is the work of Nature alone.

In and by artificial putrefaction I indeed grant it possible; but then also it is required that these sulphureous substances be at the same time mercurial. Otherwise they will never unite with mercurials, nor enter putrefaction. This union gives great trouble even to Nature herself, much more to Art—since to Art it is only given to raise created things to a higher degree, not to constitute them from first causes.

And although through certain miserable butcheries some auriform body may be composed, yet it will never sustain all the tests of genuine gold, but in one or another it will perish.

I myself have always laughed at the vainest wishes of our laboring brethren, when they say: “If only I had some particular by which I could support myself, most gladly would I give up that famous Philosophers’ Stone. I seek nothing but some certain particular,” etc.

But listen, dearest Simplician: one grain of gold, to be constituted and made out of not-gold, requires the same process and the same labors as a whole hundredweight. He who knows the part will not be ignorant of the whole, which is constituted from parts.

As for those extractions or golden solutions from ores sometimes auriferous, of these I do not dispute, since here no metamorphosis takes place, but only a most beggarly extraction of gold. More praiseworthy is the fixation of volatile minerals by fiery salts, though it requires much time. The same must be said of the reductions of metals and their maturations; because in these the mercurial part is not separated from the sulphureous, but the sulphur in its own ☿ Mercury is further cooked.

A true particulare, however, in the sound sense, is nothing else than an imperfect tincture. For all tinctures, after the first rotation, tinge lightly, and only attack the purer part of the metal.

Therefore I advise all investigators of this art, not to gape after these false particulars, but to learn at the cost and ruin of others. Nay, worse than dogs and serpents, let them flee the cobwebs of these absurdities. For such men are for the most part either active or passive impostors—which is also plain from this: If they know how in some weeks or a few months, with slight labor, to construct gold and silver in valuable quantity, why do they seek subsidies from Princes? And why do they not keep silent like the Adepts, for fear of most certain peril? This, indeed, is what I said: either their gold cannot endure the torture of fire and the devouring of the wolf, or it is compounded without profit because of sophistical principles.

But it will ever remain true, what Arnold, Chap. 3 of his Rosarium, cites from Aristotle, Book 4 Meteororum:

“The species of metals cannot be transmuted, unless they are turned into their first matter, which is sulphur and argent-vive, not taken separately but conjoined.”

Epilogue

Here then you have, Candid Reader, what I promised at the outset of this treatise: namely, I have said enough of what you must avoid on the journey to this Sepulchre.

Go forward fearlessly; the gate is open. Nothing remains for you but to put your hand to the work.

If the Divine Power graciously favors you, you will see with your own eyes, among the most sordid wrappings, your most beloved one. Call her by her proper name, revealed to you, and she will hasten to embrace you. Thus will you obtain the ☿ Mercury so greatly cherished by the Philosophers.

There is indeed still another Mercury, equally known to me, which is called the “Duplicated.” But if you attain to the former, you will not need this; for they scarcely differ at all, since both arise from one root and subject, and only the manner of eliciting is different.

Yet lest I fail you in this one point, I tell you in truth, that the former is produced by sublimation from those bodies with which it does not naturally agree, the latter, on the contrary, as Bernard, Count of Treviso, teaches at length in his Epistola Obsequiis, etc.—whom I commend to you. And meanwhile, I remain

Your most devoted student.

LATIN VERSION

TUMULUS HERMETIS APERTUS,

in quo 1531

AD SOLEM MERIDIANUM SUNT VIDENDAE,

Antiquissimorum Sophorum absconditae veritates Physicae & Recentiorum quorundam erroneae opiniones

de laudatissimo illo liquore

MERCURIO PHILOSOPHORUM,

Ita, ut jam

Cuilibet, etiam mediocriter ingenioso, Regia via pateat ad hoc mysterium

Perquirendum, inveniendum & praeparandum,

in gratiam errantium,

Illuminatus

ab

ANONYMO PANTALEONE,

Sophiae Hermeticae Adepto.

rostat Noribergæ, apud Pauli Fürsti, Bibliopolae b. m., viduam & haeredes. An. 1676.

Epitaphium Tumuli.

Benevole Lector!

Quicumque sis, attende,

Heic licet conspicere

Monumentum Veritatis Naturalis,

Natae quidem

Benigno Coeli favore, obstetricante industria humana,

Denatae vero

Crimine lethali invidiae, jubente

Id Fatorum inclemèntia,

Dum vixit,

Gemmīs aurove nitidior, admirationum mater fuit,

Iam,

Fabula vulgi facta,

Requiescit prope Acheronta, loco

Horrido et inacces so.

Bustū custodiunt in caligine tangibili

Noctuae lugubres cum tremen-

dis inferni potestatibus.

Ossa si fors petis lustrare, scias,

Huc non cliere viam, nisi

Coelitum conductu, sub

Poena cladis ultimae,

Ingredere,

Sed non,

Nisi illuminata mente,

Et

Fido comitatus amico.

AD MOMUM

Indulge genio, Mome, & quae non capis, carpe,

eveniet tamen paulò post, ut desfleas, quae jam rides,

experieris enim serò nimis, quod verum sit adagium Graecorum

ῥᾶον μωμεῖσθαι ἢ μιμεῖσθαι,

facilius est reprehendere quam imitari.

PRÆFATIO.

Candide Lector! Ecce iterum novum Athletam; nuper in hanc arenam descendere persuasus sum, fateor, numquam enim fui intentionatus, sub vexillo calami famam capessere, eo quod à longo tempore Scriptores Chymici male audiant, & pro Impostoribus Synonymis accipiantur; An jure vel injuriâ hoc fiat, judicent prudentes. Causa vero hujus Encomii videtur esse sequens; plurimi enim ita procedunt: Ubi per aliquot annos, crumenâ & sanitate exhausti, omnes anfractus cerebri evacuârunt, merasque inanitatem ubique jam relictâs tenent, ne famam longo labore partam protinus etiam amittant, arripiunt calamum & conjiciunt

in chartam speciosos suos Processus, unicuiq; obicem ponentes, ne vilipendetur, sed pondus acquirat sua obscuritate; & licet lucrum aliquando parvum exinde emergat, malunt tamen tueri suam reputationem, & tales haberi, quales non sunt, cum ingenti laesione conscientiae, quam ingenue errores confiteri vel tacere; concludunt forsan sic: Si nil aliud reporto à meis furnis, manebit tamen mihi titulus viri docti & eloquentis; quis scit, quo modo mihi poterit prodesse, licet non in hac Provincia, juxta Poetam:

Semper tibi pendeat hamus, quo minime credis gurgite, piscis erit.

Ego vero à juventute usque pauciloquus, in progressu sinistrum omen dicacitatis Scholasticae notans, deprehendi eam, ut plurimum demonstratione reali orbatam, pauperioremque Codro, ideoque rejectâ illa, statui rem ipsam potiùs venari quàm verba, nec, secundante DEO, defuit successus, non enim darem meam Scientiam realem pro toto gazophylacio rhetorico & logico; utrumque laudo, sed non comparo. Quia verò hâc literariâ tempestate plurimos video navigare sine remis, solo opinionis vento promotos, paucosque scire, quorsùm tendant, sed tanquam Pyratas sub incertâ elevatione oberrare, sibique, per Praxin istam fatuam, aliquam nauticae Scientiae famam, conciliare. Proinde ne juventuti credulae, plus justo nebularum vendant, & multitudine mendaciorum suorum, veritatem nostram Physicam ex memoriâ mortalium planè eripiant, induxi tandem animum, venalis esse, non ut mihi gloriolam ex hoc mustaceo quaeram, sed ut errantem inter tot myriades Scriptorum in viam rectam deducam, & à scopulis naufragosis custodiam. Dubitavi quidem diù, an inter tot nugatores prostrare velim, & judicium vulgare tolerare; sed vicit amor proximi quaerentis, quod enim mihi placuisset, & aliis non displicebit. Dolendum certe est, quod sartores, sutores & cerdones longè sint honestiores quàm plurimi nostrorum scribentium; servant enim, quae promittunt, & proptereà honorem merentur: sed hi putant suo muneri satisfecisse, si disertè, tersè ac callidè multa volumina typis evulgent; an verum sit vel falsum, quod scripserint, nil spectare ad ipsos, sed plebejis convenire, se verbis alligare & promissis stare: quasi verò generosa nobilitas ex camarina mendaciorum ortum suum duxisset. Jurant quidem nonnulli per totam Oeconomiam coelestem, & secùs judicates devovent ad infima Tartara: Verùm enim verò, quàm turpiter ego & alii per nequissimas has hominiformes bestias decepti simus, non est hujus loci; fieret enim volumen, non tractatulus. Stultissima res est, & insuper inexcusabile piaculum, scribere verba sine re, & scienter posteriis imponere. Amore DEI! quid cogitatis? Christiani, si judex supremus ab omni verbo otioso rationem postulât, quid vobis fiet, qui integra volumina, sine re, posteritati venditis, & dulcissima pignora amoris, aetate, sanitate, pecuniâ, honore & vitâ privatis! quis nostrum est, qui non doleat, de hoc vel illo Authore, quod seductus ab eo sit per multos annos? quoties ego exclamo? O mihi praeteritos recreat si Jupiter annos! non quod ipsos Venere & Baccho inutiliter triverim, sed quod per multos frustraneos labores, ex iis maledictis libris haustos, tempus & sanitatem destruxerim.

Sed quid vos, librorum sputatores, angit, quod tacere non potestis, si nil nisi verba, quae pectus non exsaturant, depromere vultis? Sola certe ambitio vos strangulat & boare facit, alias nil, de vobis verum est Germanicum proverbium, viel Geschrey / und wenig Wolle. Expectate modo, crudeles posteritatis hostes! Dies suprema vobis dabit mercedem, & Tabulam primam Decalogi ita explicabit, ut secundâ non indigeatis; numquid satius fuisset, tacendo Philosophus manere, quàm scribendo impostor fieri: qui arcana non vult evulgare, si quidem maximum arcanum est, arcana arcanis tegere, ille etiam sua mendacia domi servet, iisque pinguescat. Longè melius consuluit suae famae ac conscientiae lumen illud Belgicum, Helmontius, licet non unusquisque ipsum assequatur, vera tamen scripsit; non enim est necessarium, ut quilibet e tribu Levi, similibus arcanis, pavonis in modum gestiat, sed sufficit veritatem ex propria experientia posteris reliquisse, ne scientiae et artes pereant. Qui judiciosus et ad hoc electus est, statuto tempore inveniet quod quaesivit, vel altum tacentibus processuum scriptoribus.

De me hoc sancte affirmare audeo: si librorum lectioni speculationes praetulisset, easque cum praxi copulassem, tot innumeros labores et miserias non sensissem.

Quare magnanimitate animis, sodales carissimi, praemansum quidem nil vobis praebeo, sed sequimini meum consilium: relinquite vestros processus, considerate intellectualiter subjectum quod vobis prae manu est, orate et laborate. Facem vobis praeferam, locum et materiam nomine signabo, modum etiam procedendi, quantum Conscientia permittit, tradam.

Nil scribo, nisi vera, et mea, a nemine, nisi solo Deo, per improbos labores Herculeos, a multis annis insequenter exantlatos, communicata.

Fundamentum et τὸ ὅτι dederunt libri, de caetero nihil. Ego vero in his paginis talia scripsi, qualia typis nunquam fuerunt consignata.

Estote ergo hilares, seduli ac constantes, nec desperate, quamvis non statim succedat, sed cogitate, quod secundum Graecorum proverbium:

χαλεπὰ τὰ καλά – "pulchra sunt difficilia."

Chapter 1.

Probatur Titulus.

In aprico est, nec facile negabitur, nisi ab eo, qui rerum naturalium plane est ignarus, unicam veritatem naturalem e puteo Hippocratis eruere, plus ingenii, virium, laboris ac temporis requirere, quam ipsum fontem Hippocrenen cum tota Philosophia sermonicali ebibisse, eo quod haec ex instituto, lege et observatione hominum prognata est, et pingui otio addiscitur; illa vero suos natales debet ipsi Naturae, spiritui invisibili, Deique omnipotentis Vicario, ac praeterea caliginosâ nocte Orphei in tantum premuntur, ut, si nonnunquam in lucem prodire oporteat, non uno Hercule, sed ipso domitore mundi, elemento ignis, eiusque terribili torturâ, indigeat; imo neque sic facile comparet, nisi interveniat iussus eius, coram quo montes dehiscunt et abyssus surgit.

Exemplis, si vellemus agere, maxima eorum copia ex omni saeculo suppeteret, qui nudam sine veste Dianam omni possibili modo et solertia per saxa per ignes quæsiverunt, sed vel non invenerunt, vel inventam accepto Cervino intellectu non agnoverunt, & propriis industriæ Canibus præda facti sunt. Deplorant etiamnum hodie in multis locis viduæ cum pupillis, maritorum ac parentum prodigiosam prodigalitatem, in rebus Alchymisticis sine lucro locatam, excepto, quod loco lapidis calculum, & loco tincturæ artus tremulos ac paralyticos reportârunt. Propterea tamen non sequitur; cassâ nux est, somnium & civitas Platonica, quod Alchymistæ quærunt: Tumultata siquidem est Veritas naturalis, & insuper casta Virgo, non prostitutum mercenarium, cuique obvium.

Habeant sibi stultores, quod in pice hæerent, maledicant sibi Seplastæ, quod relictâ medicinâ hominum, metallis longè firmioribus clysterem meditati sint, & malè applicaverint: Quid rei nostræ Reginæ cum Balneatoribus & Ambubajarum collegiis? Non propterea aurifaber metallorum principia callet, quod metalla ipsumq; aurum affabrè effigiare didicit: Quid rusticis intercedit familiaritatis cum hâc nostrâ Principissâ, quæ munita loca & arcem inhabitat triplici muro circumdatam?

Denique Amice Lector, nunquid putas hanc coelestem prolem carere paterna cura & amore, ita ut quilibet lascivus hircus post-habito Parentis consensu, eam in suum thalamum rapere ac violare possit? Minimè gentium. Imò ne hoc fiat, mortalium oculis erepta, & Terræ, Jovis filiæ, commissa, in ejusque gremio sepulta est. Non jacet super pulvinaría mollicula, nec splendet vestimentis purpureis auroque distinctis, nec exspatiatur per læta salicta & amoenos campos spectatum, neque spectetur ut ipsa, multò minus choreas ducit & procos quærit pro more puellarum, sed Regiâ quâdam generositate vult potiùs delitescere intra brachia saxea & cimmerias tenebras, quàm ab Indignis sub molli pluma osculari. Talis hucusque fuit nostra Titonia, eritque, donec sæculum comburatur in favillam.

Chapter 2.

Suggerit causas.

Commune dicterium perhibet, Naturæ Symmystas plerunque esse Atheos: quod absque distinctione planè falsum & sesquipedale mendacium est; Sequens verò antiquorum Magorum proverbium est verum atque longè verissimum, ubi dicunt: Nostra ars vel invenit bonum, vel facit bonum. Admiserim quidem lubens, & quotidiana Experientia loquitur, quàm plurimos artis Chrysopoeiticae amasiōs Bacchanalia per totum annum vivere, parcōsque Dei cultōrēs existere; sed hoc etiam adjecerim, quod meo et omnium rectē sentientium jūdicīo illī ipsī Pseudosophī tam longē absint ab aureō vellere, quam caelum a terrā, oriens ab occidente, et album a nigro; immo ausim asserere, numquam vixisse talem adeptum, et planē esse Sydiroxylon, sapiens impius. Hoc ad minimum verum est, quod impietas, praesertim pecuinā lasciviā, sit signum inseparabile impostoris et ignorantis.

Sapientissimus enim cordium scrutator neminī umquam claves concessit ad fontem vitae, nisi quem vitā dignum praescivit: videant ergō illī, quī ejusmodī Satyros, et bestias rationales, ob putātiam suam scientiam, magnificant, ne frustra a dumetō uvas et a tribulō ficūs exspectent.

Principalis enim causa sepultae nostrae veritatis Hermeticae est, Deus optimus maximus, secretorum omnium Parens; hic, cum oculō carnali sit incomprehensibilis, suos quoque thesauros eidem abscondit. Amici quidem aliquid praestare possunt, sed id non absque directione Protosophi altissimi, per media agentis. Et, sī vel maximē per technas politicas aliquando contingit, quod ejusmodī porcus ad delubrum venerandum Naturae adducitur, nihil tamen vel capit vel efficit, variō modō caecatus et impeditus ex justō Dei judicio.

Secunda causa hujus sepulturae sunt Adepti. Homo enim, qua talis, vix caret invidia, praesertim in rebus magnis, sicut videre est in nostrae artis Antistite, Hermete; quid enim Tabula ejus Smaragdina est obscurius? citius te triformi Pegasus expediet Chymera, quam labyrinthaeo hoc aenigmatae Oedypus.

Ejus vestigiis fideliter insecuti sunt Geber, Raymundus Lullius, Arnoldus Villanovanus & alii. Arabs, sicut ingenio magis illuminatus & judicio ponderosus, ita etiam magis distincte & dogmatice sua proposuit, reticendo tamen fere ubique vel amputando punctum, de quo lis est.

Lullius, vir ingenii subtilis ac subdoli, palpum perfecte obtrusit mundo, advertit nimirum, quod Scholae Latinae, a Graecis seductae, pro summo apice Sapientiae teneant, si quis prompte, argute & eleganter sermocinari queat; proinde, omnes angulos Logicae ac Rhetoricae excutiens, suam veritatem vestivit, obliteravit & plane sepelivit, sicut ipsius scripta contradictoria & tautologica abunde testantur; placuit tamen tunc temporis orbi literato tenerrime. Similem laudem affectatus est Arnoldus Villanovanus, magis tamen adamavit obscuritatem Laconicam, quam fraudulentam dicacitatem, scripsitque suum Rosarium Spinosum, in quo explicando ipse Apollo lassabitur: & dato, quod emolumentum aliquod senserit Pyrotechnia ex ipsorum scriptis, praedecessis saeculis, illud tamen omne iterum eversum est per novum dogma Comitis Bernhardi Trevisani, diversum plane a veterum methodo procedentis.